0 Kommentare

0 Geteilt

22 Ansichten

Verzeichnis

Elevate your Sngine platform to new levels with plugins from YubNub Digital Media!

-

Bitte loggen Sie sich ein, um liken, teilen und zu kommentieren!

-

WWW.IFLSCIENCE.COMReal Or Fake Christmas Trees: Which Is Better For The Environment?Pine vs plastic: which tree really wins for the planet?0 Kommentare 0 Geteilt 22 Ansichten

WWW.IFLSCIENCE.COMReal Or Fake Christmas Trees: Which Is Better For The Environment?Pine vs plastic: which tree really wins for the planet?0 Kommentare 0 Geteilt 22 Ansichten -

WWW.IFLSCIENCE.COMWhy Does The Latest Sunrise Of The Year Not Fall On The Winter Solstice?The days are getting longer in the Northern Hemisphere, but dawn will get later still.0 Kommentare 0 Geteilt 22 Ansichten

WWW.IFLSCIENCE.COMWhy Does The Latest Sunrise Of The Year Not Fall On The Winter Solstice?The days are getting longer in the Northern Hemisphere, but dawn will get later still.0 Kommentare 0 Geteilt 22 Ansichten -

WWW.IFLSCIENCE.COMSheep And... Rhinos? Theres A Very Cute Reason You See Them Hanging Out TogetherAs emotional support pals go, its pretty damn adorable.0 Kommentare 0 Geteilt 22 Ansichten

WWW.IFLSCIENCE.COMSheep And... Rhinos? Theres A Very Cute Reason You See Them Hanging Out TogetherAs emotional support pals go, its pretty damn adorable.0 Kommentare 0 Geteilt 22 Ansichten -

WWW.IFLSCIENCE.COMWhales Living To 200 May Actually Be The Norm Theres A Sad Reason Why We Dont Know YetStick around for another 100 years and we may find out.0 Kommentare 0 Geteilt 22 Ansichten

WWW.IFLSCIENCE.COMWhales Living To 200 May Actually Be The Norm Theres A Sad Reason Why We Dont Know YetStick around for another 100 years and we may find out.0 Kommentare 0 Geteilt 22 Ansichten -

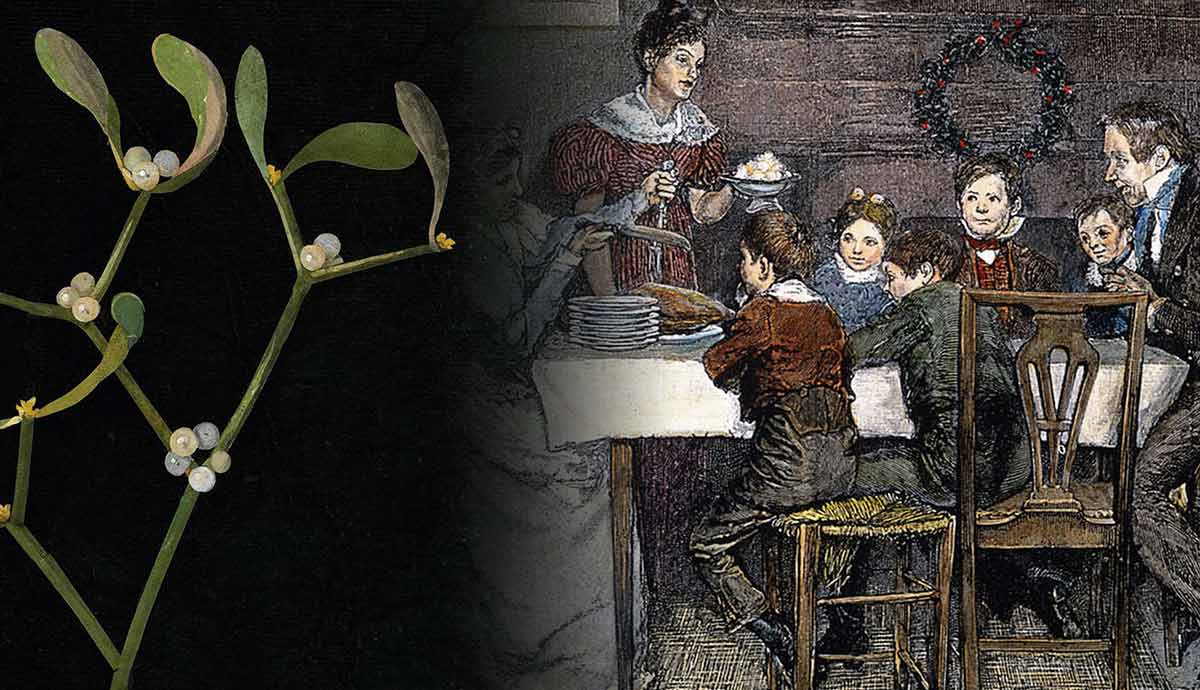

WWW.THECOLLECTOR.COM5 Victorian Christmas Traditions That Created the Christmas We KnowThroughout the 19th century, the Victorians grew utterly obsessed with Christmas. New Christmas traditions and treats were made popular by the royal family and soon caught on in ordinary Victorian homes. Many of these are still favored today. But which of our favorite Christmas traditions can we credit to the Victorians? Read on to find outChristmas in the Victorian PeriodChristmas tree, photo by Elliott B. Source: UnsplashOne of the major cultural shifts within the Victorian Period was introduced as a result of the Industrial Revolution. With more employment than ever before in factories across the country, workers rights were considered in Parliament. The 1833 Factory Act established Christmas Day (Dec 25) and Boxing Day (Dec 26) as official holidays for working people, which marked a major shift in celebration conventionsthough this did still vary depending on employer policies. December 26 became colloquially known as Boxing Day because servants and working people would open Christmas boxes from their employers, which included giftsoften of food and drink.Gifts, too, became more accessible for the middle classes as industrialization transformed how goods were made. Factories replaced the small workshops that made hand-made toys, allowing for toys to be produced quickly and in far greater quantities than before. Items like skipping ropes and wooden trains were more readily available for giving as Christmas presents.This shift also changed how families approached Christmas. With an expanding market of affordable items on offer, gifting became a more central part of the season, especially for children. Stores and markets began to display arrays of dolls, puzzles, games, and novelty items, encouraging a culture of browsing and buying in the weeks before Christmas.As these new consumer habits took hold, Christmas began to feel more structured and celebratory than it had in earlier generations. Households paid greater attention to decorating their homes, sharing special meals, and observing rituals that marked the holiday as distinct from the rest of the winter calendar. This atmosphere of anticipation and celebration created fertile ground for new customs to flourish.1. The Christmas TreeThe royal family decorate a Christmas tree, from Illustrated London News, 1848. Source: Ashmolean MuseumThe monarch, Queen Victorianamesake of the eradelighted in Christmas. In large part, this was thanks to her husband, Prince Albert. Having moved to England to marry the queen, Albert brought many of the traditions of his Germanic heritage along with him.One of these traditions was the humble Christmas tree, which originated in 16th-century Germany, evolving out of early German customs such as the paradise tree (a fir tree adorned with apples for Adam & Eve day).Queen Charlotte, the wife of King George III, was from Germany and first introduced a Christmas tree to Windsor Castle in 1800. The tradition caught on among the upper classes, but didnt reach much wider until Prince Albert married Queen Victoria, and an image of the family around a decorated tree was published in the December 1848 Christmas Supplement to the Illustrated London News. The image depicted Queen Victoria, Prince Albert, and their family members admiring the Windsor Castle Christmas tree, decorated with ornaments and lit candles. The tradition caught on! The image was hugely popular and influenced many to bring evergreens inside their homes to be decorated.Since lit candles posed obvious fire risks, less hazardous decorations included gingerbread, stars, ribbons, cakes, and candied fruits as well as hand-made decorations made from paper and card.Together, these developments reshaped the season into a shared cultural event, with an emphasis on a domestic togetherness that was rich with ritual.2. Christmas CrackersChristmas Crackers, by Nick Fewings. Source: UnsplashLondon confectioner Tom Smith invented Christmas crackers in 1847. Smith ran a popular sweet shop and visited Paris on a sourcing trip. While there, he learnt of the French custom of giving children bonbons. These sweets of sugared almonds wrapped in twisted colored paper often contained a loving message inside.Smith spotted the marketing potential of a sweet with a hidden message and brought the idea back to England for his own business. He experimented with the contents, and replaced the bonbon with toys or trinkets.The experimentation led him to design a snap mechanism which triggered when the wrapping was pulled open. The mechanism was made of two layered strips of paper, with silver fulminate on one side and an abrasive surface on the other. When pulled, the friction caused an explosion. Smith called it the Bangs of Expectation, but thanks to the onomatopoeic cracking noise, it soon became known as a cracker.3. Gift-GivingChristmas Presents, photo by Mel Poole. Source: UnsplashQueen Victoria adored presents, both the giving and the receiving. She insisted that unwrapped presents should be spread out across tables, so they could be seen and enjoyed. Although gift-giving in winter is a very ancient practice, it was popularized by the Victorians.The royal household gave gifts to all their staff on Christmas Eve; this could be anything from small trinkets to books or clothing. The most lavish gifts were from Victoria and Albert to one anotherjewelry, art, even puppies, were regularly exchanged.Ordinary Victorians would not have experienced the same luxuries, though small tokens were often exchanged on Christmas Eve.4. Christmas DinnerThe Cratchits Christmas dinner in Dickenss A Christmas Carol, as illustrated by E. A. Abbey, 1872. Source: Library of CongressChristmas Dinner was a growing tradition in the Victorian Era, again popularized by the royals.The Christmas Luncheon of the royal household was a multi-course extravaganza. Queen Victoria and Prince Albert dined on courses of pies, soups, turkey, goose, sausages, plum puddings, and mince pies.Many Victorian families re-created the Christmas Dinner in their own ways. Some joined a goose club created by local butchers, which incentivized the purchase of birds for roasting by introducing payment plans, so that buyers could pay for their goose in installments throughout the year.Christmas dinner, photo by Krackenimages. Source: UnsplashIn Charles Dickenss A Christmas Carol, the impoverished Cratchit family finds joy in the smallness of their feast:There never was such a goose. Bob said he didnt believe there ever was such a goose cooked. Its tenderness and flavour, size and cheapness, were the themes of universal admiration. Eked out by apple-sauce and mashed potatoes, it was a sufficient dinner for the whole family; indeed, as Mrs Cratchit said with great delight (surveying one small atom of a bone upon the dish), they hadnt ate it all at last! Yet everyone had had enough, and the youngest Cratchits in particular, were steeped in sage and onion to the eyebrows!In half a minute Mrs Cratchit entered: flushed, but smiling proudly: with the pudding, like a speckled cannon-ball, so hard and firm, blazing. In half of half-a-quartern of ignited brandy, and bedight with Christmas holly stuck into the top, Oh, a wonderful pudding Bob Cratchit said, and calmly too, that he regarded it as the greatest success achieved by Mrs Cratchit since their marriage. Mrs Cratchit said that now the weight was off her mind, she would confess she had had her doubts about the quantity of flour. Everybody had something to say about it, but nobody said or thought it was at all a small pudding for a large family. It would have been flat heresy to do so. Any Cratchit would have blushed to hint at such a thing.5. MistletoePaper collage by Mary Delany, 1789. Source: Wikimedia CommonsKissing under the mistletoe had become popular in the centuries before the Victorian Era. However, Victorian tradition introduced superstition to the custom. It was said that any maiden who refused the offer of a kiss under a hanging bough of mistletoe would not be married in the following year.This was made all the more menacing as the mistletoe plant was symbolic of romance, love, and fertility. Victorians created kissing balls out of sprigs of mistletoe and evergreens, arranging them in elaborate spheres for hanging in a doorway or a stairwell.0 Kommentare 0 Geteilt 14 Ansichten

WWW.THECOLLECTOR.COM5 Victorian Christmas Traditions That Created the Christmas We KnowThroughout the 19th century, the Victorians grew utterly obsessed with Christmas. New Christmas traditions and treats were made popular by the royal family and soon caught on in ordinary Victorian homes. Many of these are still favored today. But which of our favorite Christmas traditions can we credit to the Victorians? Read on to find outChristmas in the Victorian PeriodChristmas tree, photo by Elliott B. Source: UnsplashOne of the major cultural shifts within the Victorian Period was introduced as a result of the Industrial Revolution. With more employment than ever before in factories across the country, workers rights were considered in Parliament. The 1833 Factory Act established Christmas Day (Dec 25) and Boxing Day (Dec 26) as official holidays for working people, which marked a major shift in celebration conventionsthough this did still vary depending on employer policies. December 26 became colloquially known as Boxing Day because servants and working people would open Christmas boxes from their employers, which included giftsoften of food and drink.Gifts, too, became more accessible for the middle classes as industrialization transformed how goods were made. Factories replaced the small workshops that made hand-made toys, allowing for toys to be produced quickly and in far greater quantities than before. Items like skipping ropes and wooden trains were more readily available for giving as Christmas presents.This shift also changed how families approached Christmas. With an expanding market of affordable items on offer, gifting became a more central part of the season, especially for children. Stores and markets began to display arrays of dolls, puzzles, games, and novelty items, encouraging a culture of browsing and buying in the weeks before Christmas.As these new consumer habits took hold, Christmas began to feel more structured and celebratory than it had in earlier generations. Households paid greater attention to decorating their homes, sharing special meals, and observing rituals that marked the holiday as distinct from the rest of the winter calendar. This atmosphere of anticipation and celebration created fertile ground for new customs to flourish.1. The Christmas TreeThe royal family decorate a Christmas tree, from Illustrated London News, 1848. Source: Ashmolean MuseumThe monarch, Queen Victorianamesake of the eradelighted in Christmas. In large part, this was thanks to her husband, Prince Albert. Having moved to England to marry the queen, Albert brought many of the traditions of his Germanic heritage along with him.One of these traditions was the humble Christmas tree, which originated in 16th-century Germany, evolving out of early German customs such as the paradise tree (a fir tree adorned with apples for Adam & Eve day).Queen Charlotte, the wife of King George III, was from Germany and first introduced a Christmas tree to Windsor Castle in 1800. The tradition caught on among the upper classes, but didnt reach much wider until Prince Albert married Queen Victoria, and an image of the family around a decorated tree was published in the December 1848 Christmas Supplement to the Illustrated London News. The image depicted Queen Victoria, Prince Albert, and their family members admiring the Windsor Castle Christmas tree, decorated with ornaments and lit candles. The tradition caught on! The image was hugely popular and influenced many to bring evergreens inside their homes to be decorated.Since lit candles posed obvious fire risks, less hazardous decorations included gingerbread, stars, ribbons, cakes, and candied fruits as well as hand-made decorations made from paper and card.Together, these developments reshaped the season into a shared cultural event, with an emphasis on a domestic togetherness that was rich with ritual.2. Christmas CrackersChristmas Crackers, by Nick Fewings. Source: UnsplashLondon confectioner Tom Smith invented Christmas crackers in 1847. Smith ran a popular sweet shop and visited Paris on a sourcing trip. While there, he learnt of the French custom of giving children bonbons. These sweets of sugared almonds wrapped in twisted colored paper often contained a loving message inside.Smith spotted the marketing potential of a sweet with a hidden message and brought the idea back to England for his own business. He experimented with the contents, and replaced the bonbon with toys or trinkets.The experimentation led him to design a snap mechanism which triggered when the wrapping was pulled open. The mechanism was made of two layered strips of paper, with silver fulminate on one side and an abrasive surface on the other. When pulled, the friction caused an explosion. Smith called it the Bangs of Expectation, but thanks to the onomatopoeic cracking noise, it soon became known as a cracker.3. Gift-GivingChristmas Presents, photo by Mel Poole. Source: UnsplashQueen Victoria adored presents, both the giving and the receiving. She insisted that unwrapped presents should be spread out across tables, so they could be seen and enjoyed. Although gift-giving in winter is a very ancient practice, it was popularized by the Victorians.The royal household gave gifts to all their staff on Christmas Eve; this could be anything from small trinkets to books or clothing. The most lavish gifts were from Victoria and Albert to one anotherjewelry, art, even puppies, were regularly exchanged.Ordinary Victorians would not have experienced the same luxuries, though small tokens were often exchanged on Christmas Eve.4. Christmas DinnerThe Cratchits Christmas dinner in Dickenss A Christmas Carol, as illustrated by E. A. Abbey, 1872. Source: Library of CongressChristmas Dinner was a growing tradition in the Victorian Era, again popularized by the royals.The Christmas Luncheon of the royal household was a multi-course extravaganza. Queen Victoria and Prince Albert dined on courses of pies, soups, turkey, goose, sausages, plum puddings, and mince pies.Many Victorian families re-created the Christmas Dinner in their own ways. Some joined a goose club created by local butchers, which incentivized the purchase of birds for roasting by introducing payment plans, so that buyers could pay for their goose in installments throughout the year.Christmas dinner, photo by Krackenimages. Source: UnsplashIn Charles Dickenss A Christmas Carol, the impoverished Cratchit family finds joy in the smallness of their feast:There never was such a goose. Bob said he didnt believe there ever was such a goose cooked. Its tenderness and flavour, size and cheapness, were the themes of universal admiration. Eked out by apple-sauce and mashed potatoes, it was a sufficient dinner for the whole family; indeed, as Mrs Cratchit said with great delight (surveying one small atom of a bone upon the dish), they hadnt ate it all at last! Yet everyone had had enough, and the youngest Cratchits in particular, were steeped in sage and onion to the eyebrows!In half a minute Mrs Cratchit entered: flushed, but smiling proudly: with the pudding, like a speckled cannon-ball, so hard and firm, blazing. In half of half-a-quartern of ignited brandy, and bedight with Christmas holly stuck into the top, Oh, a wonderful pudding Bob Cratchit said, and calmly too, that he regarded it as the greatest success achieved by Mrs Cratchit since their marriage. Mrs Cratchit said that now the weight was off her mind, she would confess she had had her doubts about the quantity of flour. Everybody had something to say about it, but nobody said or thought it was at all a small pudding for a large family. It would have been flat heresy to do so. Any Cratchit would have blushed to hint at such a thing.5. MistletoePaper collage by Mary Delany, 1789. Source: Wikimedia CommonsKissing under the mistletoe had become popular in the centuries before the Victorian Era. However, Victorian tradition introduced superstition to the custom. It was said that any maiden who refused the offer of a kiss under a hanging bough of mistletoe would not be married in the following year.This was made all the more menacing as the mistletoe plant was symbolic of romance, love, and fertility. Victorians created kissing balls out of sprigs of mistletoe and evergreens, arranging them in elaborate spheres for hanging in a doorway or a stairwell.0 Kommentare 0 Geteilt 14 Ansichten -

WWW.THECOLLECTOR.COMHow Did Pidgin and Creole Languages Develop in the Pacific?Both pidgin and creole languages are products of colonialism, contact languages that developed when groups speaking different languages needed a shared means of communication. Typically, the lexifierthe dominant language that contributes most of the vocabulary and grammarhas been English, though there are instances of pidgins based on French and Basque as well. While pidgins, such as the Broome Pearling Lugger Pidgin, are simplified languages with limited vocabulary and basic grammatical structures, creoles are more developed pidgins that have stabilized and are now used as a primary or native language, particularly by children. Creoles, such as the Torres Strait and Roper River Kriol in Australia, are fully-fledged languages with complex structures and rich vocabularies.The Pidgins and Creoles of MelanesiaSouth Sea whalers boiling blubber, watercolor by Sir Oswald Brierly, 1876. Source: Wikimedia CommonsEstimates suggest that between 20 to 30 pidgin and Creole languages are currently spoken across various islands in the Pacific. Melanesia is one of the most linguistically rich and diverse regions in the world, with Papua New Guinea being the most linguistically diverse country globally, featuring at least 840 known languages spoken by its inhabitants.The so-called Early Melanesian Pidgin emerged in the 19th century when Europeans, along with Australians and Americans, began establishing trading stations for whaling, sandalwood, and bche-de-mer (trepang) in Melanesia. Locals, who spoke thousands of sometimes very different languages, communicated with the English-speaking newcomers through a mix of simplified English and gestures. Over the following decades, the Early Melanesian Pidgin spread extensively across the various Melanesian islands, evolving under the influence of the local languages. As a result, three different pidgins are now spoken in Vanuatu, the Solomon Islands, and Papua New Guinea.Solomon Islands, photograph by Gilly Tanabose. Source: UnsplashTok Pisin (formerly known as Neo-Melanesian) is an English-based pidgin spoken in Papua New Guinea, particularly in the islands mixed urban areas. It is one of Papua New Guineas three official languages, along with English and Hiri Motu. Hiri Motu itself (initially called Police Motu) is a pidginized form of Motu (or True Motu), the Central Papuan Tip language spoken predominantly in the Port Moresby region. Tok Pisin developed during the latter half of the 19th century on the islands sugarcane and copra plantations, where most workers came from Malaysia, Melanesia, and China.The distinction between pidgins and creoles continues to be debated and can change as the status of languages evolves. For instance, Tok Pisin is sometimes classified as a pidgin, an expanded pidgin, or even a creole due to its complexity and extensive use as a vernacular rather than merely as a lingua franca.Vanuatu, photograph by Sebastian Luo. Source: UnsplashBislama, known as bichelamar among the French, is the national language of the Republic of Vanuatu, formerly known as the New Hebrides, a volcanic archipelago in the South Pacific Ocean, east of New Guinea and southeast of Solomon Islands. Bislama is an English-based pidgin, with over 95% of its vocabulary derived from English. The rest largely comes from French and the local Austronesian languages of Vanuatu.The origins and development of Bislama are closely linked to the history of Australia, particularly to the shameful phenomenon now referred to as blackbirding. When former blackbirdsSouth Sea Islander men and women who were kidnapped or employed on plantations in Queensland, Samoa, Fiji, and New Caledoniawere finally able to return to their native islands, they brought with them the pidgin they had learned.South Sea Islander women working on a sugarcane plantation near Cairns, Queensland, 1895. Source: National Museum of AustraliaOver the years, Pijin, the English-based pidgin language spoken extensively in the Solomon Islands, has effectively become the unofficial national language of the six major islands and approximately 900 smaller islands that make up the Solomons, or Solomon Aelan, as they are known in Pijin. About 80% of its vocabulary is derived from English, its main lexifier. Pijin is closely related to both Tok Pisin and Bislama in terms of its history and linguistic origins; today, it is spoken as a main language in urban centers and as a secondary language in most rural areas.Aboriginal EnglishAboriginal Australians employed in R.A. Cunninghams touring company in Germany, photograph by Julius Schaar, 1885. Source: National Portrait GalleryMany Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders today speak Standard Australian English (AusE), the language of colonization that was imposed on their ancestors at the expense of their ancestral languages. However, an estimated 80% of Aboriginal Australians regularly speak Aboriginal English (AbE) as a first, and often only, language.Aboriginal English is a diverse collection of dialects that lie between Standard Australian English (AusE) and the various Aboriginal languages and creoles spoken throughout Australia. As Sharon Davis notes in an article for AIATSIS, the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, AbE is not a form of AusE, but rather both are varieties of English. Like any language, Aboriginal English features heavy and light varieties, with the latter often being inaccessible to outsiders and those who do not speak AbE.Survey team working for the Northern Territory Public Works Department, photograph by Anton Faymann, 1957-58. Source: Wikimedia CommonsSome linguists believe that in certain communities Aboriginal English did not evolve from a pidgin-based language but instead emerged from an Aboriginalization of English, with Aboriginal speakers adapting English by incorporating specific accents, rhythms, words, and phrases from their ancestral languages. In this context, English was shaped by the local Aboriginal languages, rather than the reverse. Sharon Davis also points out that Aboriginal English is not formally taught in schools or universities because it is a community-developed language that belongs to community.In AbE, constructions such as uninverted questions (Thats your car? instead of Is that your car?) and double negatives are rather common. These should not be considered grammatical errors but different grammatical rules consistent with Aboriginal English. Nowadays, given the racist use of pidgin languages by non-Indigenous Australians in the past, using the term pidgin English in regards to Aboriginal English is often considered offensive.In Australias central desert regions, in present-day Northern Territory, as well as northern Queensland and parts of Western Australia, European encroachment proceeded much slower than in the rest of the country, photograph by Damien Tait. Source: UnsplashIt is worth remembering that the colonization of Australia did not occur uniformly across the continent. The southern regions, specifically present-day Victoria and New South Wales were the first to be settled. By the 1850s, Aboriginal customs and traditional ways of life had already experienced a significant decline.In contrast, in the tropical north and the central desert regionsincluding what is now northern Queensland, the Northern Territory, and part of Western AustraliaEuropean encroachment proceeded at a slower pace, allowing Aboriginal lifestyles and languages to remain largely intact for many years. The evolution of Aboriginal English dialects and the survival or extinction of Indigenous languages reflect the different phases of European colonization and the development of Indigenous-settler relations since the onset of colonialism.Torres Strait CreoleCatching sardines in the Torres Strait in a picture that is part of the Williamson Collection assembled by Archdeacon A.N. Williamson, 1900s-1930s. Source: Wikimedia CommonsTorres Strait Creole, also known as Yumplatok and Ailan Tok, is an English-based creole spoken by Aboriginal communities on various Torres Strait Islands, situated between the northern tip of Queensland and Papua New Guinea, as well as in southwestern coastal Papua New Guinea, and Northern Cape York on mainland Australia. In Queensland, particularly in coastal communities such as Brisbane, Townsville, Cairns, Mackay, and Rockhampton, it is the most widely spoken Indigenous language, used as either a first or second language.Torres Strait Creole originated in the 1870s as a pidgin language that served as a bridge between locals and English-speaking newcomerstraders, missionaries, workers, and settlers. It quickly evolved into a full creole.Torres Strait Islanders, who were discouraged and actively prevented from speaking their ancestral languages, began to incorporate words and distinctive structures from their languages, particularly Meriam Mir and Kala Lagaw Ya, along with expressions from Standard Australian English.Double outrigger canoe made of cedar, palm, bamboo, and grass from Saibai Island, in the Torres Strait, 2000. Source: National Museum of AustraliaSome Yumplatok words also derive from Japanese, Malay, and various languages spoken in Papua New Guinea, such as Bine, Kiwai, Motu, and Gizrra. Overall, Torres Strait Creole shows more similarities with Pacific creoles and pidgins, such as Tok Pisin, Bislama, and Pijin, rather than other creole languages spoken on mainland Australia.While the vocabulary mainly comes from English, the sentence structure and verb conjugations are influenced by Torres Strait languages, and its phonology and pronunciation borrow heavily from both groups. Today, Torres Strait Creole continues to be used by thousands of people7,380 persons, according to the 2021 censuseither as a first or second language.Roper River KriolRoper River Mission, renamed Ngukurr in 1988. Source: Wikimedia CommonsUnlike Yumplatok, Kriol (also known as Roper River Kriol) descends from the Port Jackson Pidgin English (PJPE), which developed upon contact between Aboriginal people and British colonizers in the area that is now Sydney, New South Wales, during the early days of colonization. Kriol is still spoken in the Top End and the Kimberley region. PJPE gradually died out in most parts of Australia but persisted in the Northern Territory. Linguists call this variant Northern Territory Pidgin English (NTPE).By the turn of the 20th century, the language had stabilized and creolized, meaning, it developed from a contact language pidgin into a fully functioning creole, with its own unique rules, pronunciation, and grammatical structures, particularly on cattle stations, missions, and reserves. The Roper River Mission (now known by its Aboriginal name Ngukurr) was the first place where it consistently creolized.Missions and reserves in Australia. Source: Australian MuseumIn 1908, around 200 Aboriginal people from different tribes lived among Anglican missionaries in the Roper River region. Their children spoke different languages but were placed into dormitories together, which facilitated the creolization of the contact language they spoke, despite the missionaries efforts to teach children Standard English as their first language.Kriol is now the largest language spoken exclusively in Australia and the second most common language in the Northern Territory. Because it is generally difficult for non-speakers to understand and nearly incomprehensible to those who only speak Standard English, Kriol (and Yumplatok) speakers have often faced discrimination, both physical and psychological. Like Aboriginal English, Kriol is a language deeply rooted in the communities where it is spoken. It is a distinct language from English, fully functional, complex, sophisticated, and expressive enough to be used to translate Shakespeares works and the Bible.Broome Pearling Lugger PidginJapanese pearl divers in Broome, 1914. Source: National Museum of AustraliaBy the turn of the 20th century, Broome (or Rubibi, as called by the Yawuru people) became the center of the pearling industry, catering to the increasing European and American demand for large pearl shell buttons and mother-of-pearl shells used for buckles, cufflinks, musical instruments, and cutlery handles. By 1900, Western Australia experienced a boom in the pearling industry. Infrastructure such as hospitals, roads, stores, and jails were built to support the pearling fleets along the coast, from Shark Bay in the south to King Sound in the north.Broome, a coastal town in the Kimberley region of present-day Western Australia, attracted workers from Japan, China, and Korea, who often integrated with local Aboriginal tribes and Torres Strait Islanders, despite the rising white Australia movement and anti-Asia discrimination. For decades, pearling represented not only a significant source of income but also a point of pride for Aboriginal, Islander, and Asian communities in Australia.Broome, Western Australia, photograph by Paul-Alain Hunt. Source: UnsplashPearlers, both men and women, came from various cultural, linguistic, and socioeconomic backgrounds. Some were Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, while others were Asian or European. In this rich, multicultural, and multilingual environment, the Broome Pearling Lugger Pidgin emerged. This language served as a bridge for communication between Aboriginal people, Malays, Japanese, Torres Strait Islanders, Koreans, and Chinese workers on pearling boats around Broome and the north coast of Western Australia.The primary lexifier of the Broome Pearling Lugger Pidgin was not English, but Kupang Malay. Its vocabulary and grammar were influenced by Malay, Japanese, Chinese, and local Aboriginal languages, as well as Englishthough some linguists note that the English terms used were more similar to Aboriginal Australian than Standard Australian English. The Broome Pearling Lugger Pidgin ceased to be used in the 1960s.South Sea Islander wooden figure, 1914. Source: British MuseumIts history reflects the changing demographics of the pearling workforce. As the workforce became more ethnically uniformparticularly following the 1901 Immigration Restriction Act and after World War I and World War IIthe need for the language diminished, leading to its gradual decline in use.The origins and development of pidgins, from Tok Pisin to Bislama and the Broome Pearling Lugger Pidgin, as well as creole languages such as the Torres Strait and Roper River Kriol, are revealing of the colonial history of most countries in the Pacific. From Australia to Papua New Guinea, from Vanuatu to the Solomon Islands, pidgins emerged when the local population came into contact with newcomerstypically Anglophone settlers, traders, and whalerswho required a common language for communication.Over time, some pidgins evolved into more complex forms and eventually became the first languages of some communities. In the Pacific, as in North America, languages continue to reflect historical events and socio-economic developments.0 Kommentare 0 Geteilt 14 Ansichten

WWW.THECOLLECTOR.COMHow Did Pidgin and Creole Languages Develop in the Pacific?Both pidgin and creole languages are products of colonialism, contact languages that developed when groups speaking different languages needed a shared means of communication. Typically, the lexifierthe dominant language that contributes most of the vocabulary and grammarhas been English, though there are instances of pidgins based on French and Basque as well. While pidgins, such as the Broome Pearling Lugger Pidgin, are simplified languages with limited vocabulary and basic grammatical structures, creoles are more developed pidgins that have stabilized and are now used as a primary or native language, particularly by children. Creoles, such as the Torres Strait and Roper River Kriol in Australia, are fully-fledged languages with complex structures and rich vocabularies.The Pidgins and Creoles of MelanesiaSouth Sea whalers boiling blubber, watercolor by Sir Oswald Brierly, 1876. Source: Wikimedia CommonsEstimates suggest that between 20 to 30 pidgin and Creole languages are currently spoken across various islands in the Pacific. Melanesia is one of the most linguistically rich and diverse regions in the world, with Papua New Guinea being the most linguistically diverse country globally, featuring at least 840 known languages spoken by its inhabitants.The so-called Early Melanesian Pidgin emerged in the 19th century when Europeans, along with Australians and Americans, began establishing trading stations for whaling, sandalwood, and bche-de-mer (trepang) in Melanesia. Locals, who spoke thousands of sometimes very different languages, communicated with the English-speaking newcomers through a mix of simplified English and gestures. Over the following decades, the Early Melanesian Pidgin spread extensively across the various Melanesian islands, evolving under the influence of the local languages. As a result, three different pidgins are now spoken in Vanuatu, the Solomon Islands, and Papua New Guinea.Solomon Islands, photograph by Gilly Tanabose. Source: UnsplashTok Pisin (formerly known as Neo-Melanesian) is an English-based pidgin spoken in Papua New Guinea, particularly in the islands mixed urban areas. It is one of Papua New Guineas three official languages, along with English and Hiri Motu. Hiri Motu itself (initially called Police Motu) is a pidginized form of Motu (or True Motu), the Central Papuan Tip language spoken predominantly in the Port Moresby region. Tok Pisin developed during the latter half of the 19th century on the islands sugarcane and copra plantations, where most workers came from Malaysia, Melanesia, and China.The distinction between pidgins and creoles continues to be debated and can change as the status of languages evolves. For instance, Tok Pisin is sometimes classified as a pidgin, an expanded pidgin, or even a creole due to its complexity and extensive use as a vernacular rather than merely as a lingua franca.Vanuatu, photograph by Sebastian Luo. Source: UnsplashBislama, known as bichelamar among the French, is the national language of the Republic of Vanuatu, formerly known as the New Hebrides, a volcanic archipelago in the South Pacific Ocean, east of New Guinea and southeast of Solomon Islands. Bislama is an English-based pidgin, with over 95% of its vocabulary derived from English. The rest largely comes from French and the local Austronesian languages of Vanuatu.The origins and development of Bislama are closely linked to the history of Australia, particularly to the shameful phenomenon now referred to as blackbirding. When former blackbirdsSouth Sea Islander men and women who were kidnapped or employed on plantations in Queensland, Samoa, Fiji, and New Caledoniawere finally able to return to their native islands, they brought with them the pidgin they had learned.South Sea Islander women working on a sugarcane plantation near Cairns, Queensland, 1895. Source: National Museum of AustraliaOver the years, Pijin, the English-based pidgin language spoken extensively in the Solomon Islands, has effectively become the unofficial national language of the six major islands and approximately 900 smaller islands that make up the Solomons, or Solomon Aelan, as they are known in Pijin. About 80% of its vocabulary is derived from English, its main lexifier. Pijin is closely related to both Tok Pisin and Bislama in terms of its history and linguistic origins; today, it is spoken as a main language in urban centers and as a secondary language in most rural areas.Aboriginal EnglishAboriginal Australians employed in R.A. Cunninghams touring company in Germany, photograph by Julius Schaar, 1885. Source: National Portrait GalleryMany Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders today speak Standard Australian English (AusE), the language of colonization that was imposed on their ancestors at the expense of their ancestral languages. However, an estimated 80% of Aboriginal Australians regularly speak Aboriginal English (AbE) as a first, and often only, language.Aboriginal English is a diverse collection of dialects that lie between Standard Australian English (AusE) and the various Aboriginal languages and creoles spoken throughout Australia. As Sharon Davis notes in an article for AIATSIS, the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, AbE is not a form of AusE, but rather both are varieties of English. Like any language, Aboriginal English features heavy and light varieties, with the latter often being inaccessible to outsiders and those who do not speak AbE.Survey team working for the Northern Territory Public Works Department, photograph by Anton Faymann, 1957-58. Source: Wikimedia CommonsSome linguists believe that in certain communities Aboriginal English did not evolve from a pidgin-based language but instead emerged from an Aboriginalization of English, with Aboriginal speakers adapting English by incorporating specific accents, rhythms, words, and phrases from their ancestral languages. In this context, English was shaped by the local Aboriginal languages, rather than the reverse. Sharon Davis also points out that Aboriginal English is not formally taught in schools or universities because it is a community-developed language that belongs to community.In AbE, constructions such as uninverted questions (Thats your car? instead of Is that your car?) and double negatives are rather common. These should not be considered grammatical errors but different grammatical rules consistent with Aboriginal English. Nowadays, given the racist use of pidgin languages by non-Indigenous Australians in the past, using the term pidgin English in regards to Aboriginal English is often considered offensive.In Australias central desert regions, in present-day Northern Territory, as well as northern Queensland and parts of Western Australia, European encroachment proceeded much slower than in the rest of the country, photograph by Damien Tait. Source: UnsplashIt is worth remembering that the colonization of Australia did not occur uniformly across the continent. The southern regions, specifically present-day Victoria and New South Wales were the first to be settled. By the 1850s, Aboriginal customs and traditional ways of life had already experienced a significant decline.In contrast, in the tropical north and the central desert regionsincluding what is now northern Queensland, the Northern Territory, and part of Western AustraliaEuropean encroachment proceeded at a slower pace, allowing Aboriginal lifestyles and languages to remain largely intact for many years. The evolution of Aboriginal English dialects and the survival or extinction of Indigenous languages reflect the different phases of European colonization and the development of Indigenous-settler relations since the onset of colonialism.Torres Strait CreoleCatching sardines in the Torres Strait in a picture that is part of the Williamson Collection assembled by Archdeacon A.N. Williamson, 1900s-1930s. Source: Wikimedia CommonsTorres Strait Creole, also known as Yumplatok and Ailan Tok, is an English-based creole spoken by Aboriginal communities on various Torres Strait Islands, situated between the northern tip of Queensland and Papua New Guinea, as well as in southwestern coastal Papua New Guinea, and Northern Cape York on mainland Australia. In Queensland, particularly in coastal communities such as Brisbane, Townsville, Cairns, Mackay, and Rockhampton, it is the most widely spoken Indigenous language, used as either a first or second language.Torres Strait Creole originated in the 1870s as a pidgin language that served as a bridge between locals and English-speaking newcomerstraders, missionaries, workers, and settlers. It quickly evolved into a full creole.Torres Strait Islanders, who were discouraged and actively prevented from speaking their ancestral languages, began to incorporate words and distinctive structures from their languages, particularly Meriam Mir and Kala Lagaw Ya, along with expressions from Standard Australian English.Double outrigger canoe made of cedar, palm, bamboo, and grass from Saibai Island, in the Torres Strait, 2000. Source: National Museum of AustraliaSome Yumplatok words also derive from Japanese, Malay, and various languages spoken in Papua New Guinea, such as Bine, Kiwai, Motu, and Gizrra. Overall, Torres Strait Creole shows more similarities with Pacific creoles and pidgins, such as Tok Pisin, Bislama, and Pijin, rather than other creole languages spoken on mainland Australia.While the vocabulary mainly comes from English, the sentence structure and verb conjugations are influenced by Torres Strait languages, and its phonology and pronunciation borrow heavily from both groups. Today, Torres Strait Creole continues to be used by thousands of people7,380 persons, according to the 2021 censuseither as a first or second language.Roper River KriolRoper River Mission, renamed Ngukurr in 1988. Source: Wikimedia CommonsUnlike Yumplatok, Kriol (also known as Roper River Kriol) descends from the Port Jackson Pidgin English (PJPE), which developed upon contact between Aboriginal people and British colonizers in the area that is now Sydney, New South Wales, during the early days of colonization. Kriol is still spoken in the Top End and the Kimberley region. PJPE gradually died out in most parts of Australia but persisted in the Northern Territory. Linguists call this variant Northern Territory Pidgin English (NTPE).By the turn of the 20th century, the language had stabilized and creolized, meaning, it developed from a contact language pidgin into a fully functioning creole, with its own unique rules, pronunciation, and grammatical structures, particularly on cattle stations, missions, and reserves. The Roper River Mission (now known by its Aboriginal name Ngukurr) was the first place where it consistently creolized.Missions and reserves in Australia. Source: Australian MuseumIn 1908, around 200 Aboriginal people from different tribes lived among Anglican missionaries in the Roper River region. Their children spoke different languages but were placed into dormitories together, which facilitated the creolization of the contact language they spoke, despite the missionaries efforts to teach children Standard English as their first language.Kriol is now the largest language spoken exclusively in Australia and the second most common language in the Northern Territory. Because it is generally difficult for non-speakers to understand and nearly incomprehensible to those who only speak Standard English, Kriol (and Yumplatok) speakers have often faced discrimination, both physical and psychological. Like Aboriginal English, Kriol is a language deeply rooted in the communities where it is spoken. It is a distinct language from English, fully functional, complex, sophisticated, and expressive enough to be used to translate Shakespeares works and the Bible.Broome Pearling Lugger PidginJapanese pearl divers in Broome, 1914. Source: National Museum of AustraliaBy the turn of the 20th century, Broome (or Rubibi, as called by the Yawuru people) became the center of the pearling industry, catering to the increasing European and American demand for large pearl shell buttons and mother-of-pearl shells used for buckles, cufflinks, musical instruments, and cutlery handles. By 1900, Western Australia experienced a boom in the pearling industry. Infrastructure such as hospitals, roads, stores, and jails were built to support the pearling fleets along the coast, from Shark Bay in the south to King Sound in the north.Broome, a coastal town in the Kimberley region of present-day Western Australia, attracted workers from Japan, China, and Korea, who often integrated with local Aboriginal tribes and Torres Strait Islanders, despite the rising white Australia movement and anti-Asia discrimination. For decades, pearling represented not only a significant source of income but also a point of pride for Aboriginal, Islander, and Asian communities in Australia.Broome, Western Australia, photograph by Paul-Alain Hunt. Source: UnsplashPearlers, both men and women, came from various cultural, linguistic, and socioeconomic backgrounds. Some were Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, while others were Asian or European. In this rich, multicultural, and multilingual environment, the Broome Pearling Lugger Pidgin emerged. This language served as a bridge for communication between Aboriginal people, Malays, Japanese, Torres Strait Islanders, Koreans, and Chinese workers on pearling boats around Broome and the north coast of Western Australia.The primary lexifier of the Broome Pearling Lugger Pidgin was not English, but Kupang Malay. Its vocabulary and grammar were influenced by Malay, Japanese, Chinese, and local Aboriginal languages, as well as Englishthough some linguists note that the English terms used were more similar to Aboriginal Australian than Standard Australian English. The Broome Pearling Lugger Pidgin ceased to be used in the 1960s.South Sea Islander wooden figure, 1914. Source: British MuseumIts history reflects the changing demographics of the pearling workforce. As the workforce became more ethnically uniformparticularly following the 1901 Immigration Restriction Act and after World War I and World War IIthe need for the language diminished, leading to its gradual decline in use.The origins and development of pidgins, from Tok Pisin to Bislama and the Broome Pearling Lugger Pidgin, as well as creole languages such as the Torres Strait and Roper River Kriol, are revealing of the colonial history of most countries in the Pacific. From Australia to Papua New Guinea, from Vanuatu to the Solomon Islands, pidgins emerged when the local population came into contact with newcomerstypically Anglophone settlers, traders, and whalerswho required a common language for communication.Over time, some pidgins evolved into more complex forms and eventually became the first languages of some communities. In the Pacific, as in North America, languages continue to reflect historical events and socio-economic developments.0 Kommentare 0 Geteilt 14 Ansichten -

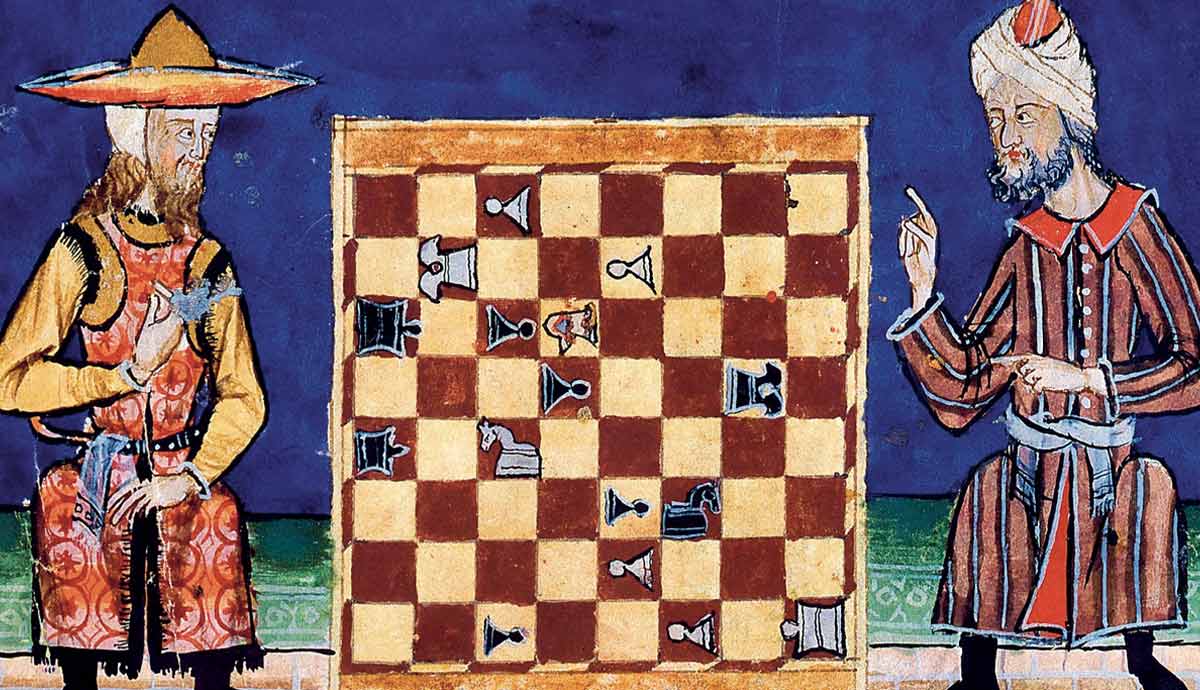

WWW.THECOLLECTOR.COMHow Were Jewish-Muslim Relations During the Islamic Golden Age?During the Middle Ages, Christian Europe was immersed in a totalizing culture of violent, oppressive antisemitism. In the Muslim world, however, life looked far different for Jewish communities. Throughout the centuries of the Islamic Golden Age, peaceful and prosperous coexistence between Muslims and Jews was the norm. What did that coexistence look like? Keep reading to find out.What Was the Islamic Golden Age?Library scene in Baghdad from The Assemblies, by Hairiri, drawn by Al-Wasit, 13th century. Source: Wikimedia CommonsThe periodization of the Islamic Golden Age varies. Some place it in the period from roughly 750 CE until 1258 CE, from the founding of the Islamic Abbasid Dynasty until the destruction of the Baghdad House of Wisdom. Others argue for a wider conception, starting as early as the 500s CE and ending as late as the 1500s CE. For the purposes of this article, we will focus on the years 750-1238 CE, the most consistent and significant period of flourishing throughout the Islamic world.The Muslim world at its height was massive. It spread throughout much of the Middle East, North Africa, and Spain, across several different dynasties the Abbasid Dynasty, centered in Baghdad, the Fatimid Dynasty, centered in Cairo, and the Umayyad Dynasty, centered in Cordoba. Each dynasty was ruled over by an Islamic religious and political leader known as a Caliph.The Islamic Golden Age was characterized by the importance placed on learning, leading to incredible achievements in the arts, sciences, and philosophy. With the great Baghdad House of Wisdom as the locus of intellectual development, great strides were made in the realms of medicine, astronomy, mathematics, and so much more. Numerous forms of education were on offer, such as in schools, libraries, and observatories.A Jew and a Muslim playing chess from El Libro de los Juegos, commissioned by Alphonse X of Castile, Madrid, 13th century. Source: Wikimedia CommonsGovernance during the Islamic Golden Age was based on Islamic religious and juridical principles. Islamic scholars carefully studied religious texts such as the Quran and the Hadiths to create the laws governing Islamic society. For instance, interest-free loans were provided for the poor, following Islamic principles condemning usury.Politics in the Muslim world was guided by a religiously informed vision of peace and justice. Outside of specifically Islamic influences, the philosophical underpinnings of Islamic political and social life were based above all on Greek philosophy and science, as well as Persian and Indian thought.Muslim imperial rule further allowed for a notable degree of cultural diversity within unity, distinguishing the Islamic world from the oppressive and suffocating Christian rule in Europe. The greater inclusivity of Muslim society was a central reason for the rapid advances made in the arts and sciences.Combat between a crusader soldier and a Muslim soldier, around 1250. Source: Radio FranceThe Islamic Golden Age suffered a slow decline as a result of the Crusades, the Mongol invasions, and a number of other political and economic factors. Eventually, Christian Europeans seized many Muslim territories, oftentimes through brutal means.Spain was conquered by the Christians at the end of the Spanish Reconquista in 1491. Amongst the Jewish communities forcefully expelled by newly Christianized Spain in 1492, a nostalgia for the much-preferable conditions of Muslim rule began to develop. This nostalgia was the original basis for the utopian conception of Jewish life during the Islamic Golden Age.The Utopian Conception of Jewish-Muslim RelationsThe Civilization of Cordoba in the Time of Abd-al-Rahman III, by Dionisio Baixeras Verdaguer, 1885. Source: University of BarcelonaModern historiographical studies of the lives of Jewish people during the Islamic Golden Age began in the early 19th century, led by the scholarship of Jewish historians. These scholars, living in the midst of horrific Western European antisemitism, dreamed of a world free of antisemitic violence and oppression. Taking cues from the previously expelled Jews of Spain, they found evidence that such a world is possible in their study of the Islamic Golden Age.These historians envisioned the Islamic Golden Age as a sort of utopia for Jewish people, relative to the horrors of the Christian West. In the Islamic Golden Age, they saw a model for widespread Jewish flourishing.According to these historians, the Muslim world during the Islamic Golden Age was uniquely tolerant of Jews and Jewish life as a whole. They cite the political and cultural achievements of Jews in the Muslim world, as well as evidence of widespread social integration, to make their point.Following the popularization of Zionism among historians in the 20th century, especially among Jewish historians, there was a tremendous backlash to the utopian conception forwarded by the early historians. These 20th and 21st-century scholars argued for a highly pessimistic view of Jewish life during the Islamic Golden Age the polar opposite of the utopian conception.The Pessimistic Conception of Jewish-Muslim RelationsTheodor Herzl At The First Zionist Congress in Basel, 1897. Source: Wikimedia CommonsDuring the 20th century, Jewish-Muslim relations steadily declined under the pressure of mass Zionist immigration to Palestine. Violence broke out between Jews and Muslims throughout the Middle East. Indigenous Jewish communities, such as those in Yemen, were increasingly persecuted by Muslims. Zionist settlers in Palestine stopped integrating into pre-existing communities and engaged in increasingly intense violence against their new majority-Muslim neighbors.In this context of ratcheting tensions between Jews and Muslims, some scholars began to argue for a pessimistic conception of Jewish life during the Islamic Golden Age. According to the pessimistic conception, Jewish life under Muslim rule was not unlike Jewish life under Christian rule: violently antisemitic and persecutory as a rule.Unsurprisingly, there is some truth in both the utopian and pessimistic conceptions of Jewish-Muslim relations during the Islamic Golden Age. Both, however, err too far in one direction or another. So, what did the reality look like?Jewish Legal Status During the Islamic Golden AgePage from a Manuscript on Islamic Law, Spain, 11th century. Source: Los Angeles County Museum of ArtThroughout the Islamic Golden Age, Jewish communities submitted to an overall condition of Muslim rule in exchange for protection against targeted persecution and oppression.Jews were allowed general cultural and political freedom, within some limitations, which were largely the same as the limitations imposed upon Christians. Both Jews and Christians, as non-Muslim monotheists, were legally categorized as dhimmi, a special legal category literally meaning protected person. Dhimmi were not subject to forced conversion, following the principle of non-compulsion laid out in the Quran (Sura 2:256). They were socially and territorially mobile.Unlike in the Christian world, dhimmi Jews were allowed to govern many of their own matters of religion, as well as family and personal matters, according to their own precepts. They could select many of their own leaders and jurists. For example, many Jewish communities maintained their own Rabbinical courts in order to adjudicate internal disputes.Some of the limitations imposed upon all dhimmi included prohibitions against constructing new religious sites, bans on public engagement in religious rituals, wearing clothing differentiating them from Muslims, and acknowledging Muslim rule. In these senses, Jews were discriminated against by the Muslim world, as were other dhimmi.However, these discriminatory practices did not amount to active, targeted persecution of the kind practiced throughout the Christian West. As other dhimmi were discriminated against in a similar manner, there was no specifically anti-Jewish intent behind the discrimination. Moreover, restrictions placed upon Jews were often ignored by local Muslim rulers. So long as Jewish communities did their duty as dhimmi, above all by paying special poll taxes and accepting Muslim superiority, many of the restrictions placed upon them were often relaxed.Jewish Intellectual and Cultural Life During the Islamic Golden AgeGreat Synagogue of Baghdad, Iraq. Source: Babylonian Jewry Heritage CenterThe mobility of Jews in the Islamic world created ideal conditions for the dissemination of Jewish culture on a much wider scale than seen anywhere else. Jewish communities could share cultural developments, exchange goods, and teach each other about unique beliefs and practices.Jews were increasingly urban throughout the Islamic Golden Age, with many moving to Baghdad. In Baghdad, two great rabbinic academies were established under Muslim rule as the centers of Jewish intellectual life. Jews from all throughout the Muslim world learned at the academies. Thousands of letters the academies sent to Jewish communitiesfrom the Mediterranean to North Africa to Spainare preserved to this day. The letters instructed Jewish communities on important matters of law and practice.Manuscript page by Maimonides, Judeo-Arabic language in Hebrew letters. Source: Wikimedia CommonsJews and Muslims commonly inhabited the same public spaces and lived side-by-side in harmony. Cross-cultural pollination between Jews and Muslims enriched the intellectual and cultural traditions of both. Jews in Baghdad, as well as other cosmopolitan centers of learning, such as Cordoba, worked in close conversation with their Muslim peers to advance the arts and sciences. Jewish thinkers developed everything from medicine to linguistics to poetry.They read and wrote in both Arabic and Hebrew, maintaining their own cultural tradition while not segregating themselves from the Muslim world around them. Arabic texts were frequently translated into Hebrew and vice-versa. For instance, the famed Jewish philosopher Maimonides was highly successful in Muslim Spain. He engaged heavily with both Hebrew and Arabic texts during his philosophical career. Thinkers such as Maimonides were accepted and honored by their Muslim peers.Jewish Economic Life During the Islamic Golden AgeA dirham of Caliph Al Mansur, 754-775 CE, photo by Jean Michel-Moullec. Source: FlickrJews in the Muslim world were full participants in economic life. They were allowed to engage in economic activities with few restrictions, in stark contrast to the Jews of Christian Europe. They commonly worked with Muslims and other non-Jews as equals, in a variety of industries.During the peak of the Islamic Golden Age, Jewish traders and merchants became heavily involved in economic life, especially in the great city of Baghdad. They were further integrated into the court of the Abbasid Dynasty in Baghdad, playing significant roles in commerce and economic administration.Other Jewish communities earned their livelihoods as everything from craftsmen to physicians to farmers to pharmacists. Many Jewish craftsmen were especially successful, producing goods for Muslims and non-Muslims alike.Jewish-Muslim economic integration helped Jewish communities maintain positive, mutually beneficial connections with Muslims. It allowed individual Jews to hold significant positions of power throughout the Muslim world and to access the wealth needed to live well.Jewish-Muslim Conflict During the Islamic Golden AgeInterior Courtyard of the Al-Hakim Mosque in Cairo, Egypt, Mosque named after the Caliph Al-Hakim, photo taken January 12, 2013. Source: Wikimedia CommonsJewish subjects of Muslim rule were rarely singled out and targeted by Muslims specifically as Jews. Most of the conflict between Jews and their Muslim sovereigns and neighbors resulted from Jews status as dhimmi.Some Muslims were suspicious of dhimmi. While dhimmi were far preferable to polytheists in the eyes of Islam, they still believed in corrupted versions of the truth and failed to accept the authority of the Prophet Muhammad. These facts led to varying degrees of distrust of dhimmi motives and actions among Muslims. However, this low-level interpersonal conflict was not universal and did not result in systematic persecution or oppression.Throughout the Islamic Golden Age, some individual Caliphs imposed limitations on Jews and other dhimmi participants in political life. Typically, these Caliphs attempted to unilaterally remove some or all dhimmi from public office. However, dhimmi were too critical to the successful administration of imperial power to be removed from all public offices, and they held significant positions of power throughout the Islamic Golden Age.Episodes of large-scale violence against Jews were exceedingly rare, but not unheard of. One 11th-century Muslim ruler, the Fatimid Caliph al-Hakim, destroyed a number of Jewish religious buildings and forcefully converted Jews in Egypt and Palestine to Islam. Another, lesser Muslim ruler attacked Jewish communities in Spain and North Africa before forcefully converting their inhabitants. Although these horrific episodes seriously harmed Jewish communities, they were not provoked by specifically anti-Jewish sentiment. Both also targeted Christians. Most infamously, Caliph al-Hakim ordered the total destruction of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and other Christian religious sites alongside Jewish ones.View of the 11th century (Zirid) walls of the Albacn district of Granada today, 2015. Source: Wikimedia CommonsThe most infamous occasion of Muslim persecution of Jews during the Islamic Golden Age was the Grenada massacre of 1066 CE. The massacre was instigated when an ambitious Jewish high official was accused of trying to overthrow the Muslim government in Granada from within. Other Grenadan Jews were suspected of being involved in the officials plot.One afternoon, after the accusation was made in public, a crowd of Muslims gathered together at the officials home. They murdered the official, then marched through the streets killing Jews and destroying Jewish property. Anti-Jewish riots and massacres sporadically occurred under similar circumstances elsewhere in the Muslim world.However, these outbursts of anti-Jewish violence and persecution were the exception, not the rule. The utopian conception of Jewish-Muslim relations during the Islamic Golden Age is an exaggeration, but it gets far closer to reality than the pessimistic conception. Jewish-Muslim relations throughout the Islamic Golden Age were overwhelmingly characterized by peaceful and prosperous co-existence within a culture of mutual acceptance and appreciation.0 Kommentare 0 Geteilt 14 Ansichten

WWW.THECOLLECTOR.COMHow Were Jewish-Muslim Relations During the Islamic Golden Age?During the Middle Ages, Christian Europe was immersed in a totalizing culture of violent, oppressive antisemitism. In the Muslim world, however, life looked far different for Jewish communities. Throughout the centuries of the Islamic Golden Age, peaceful and prosperous coexistence between Muslims and Jews was the norm. What did that coexistence look like? Keep reading to find out.What Was the Islamic Golden Age?Library scene in Baghdad from The Assemblies, by Hairiri, drawn by Al-Wasit, 13th century. Source: Wikimedia CommonsThe periodization of the Islamic Golden Age varies. Some place it in the period from roughly 750 CE until 1258 CE, from the founding of the Islamic Abbasid Dynasty until the destruction of the Baghdad House of Wisdom. Others argue for a wider conception, starting as early as the 500s CE and ending as late as the 1500s CE. For the purposes of this article, we will focus on the years 750-1238 CE, the most consistent and significant period of flourishing throughout the Islamic world.The Muslim world at its height was massive. It spread throughout much of the Middle East, North Africa, and Spain, across several different dynasties the Abbasid Dynasty, centered in Baghdad, the Fatimid Dynasty, centered in Cairo, and the Umayyad Dynasty, centered in Cordoba. Each dynasty was ruled over by an Islamic religious and political leader known as a Caliph.The Islamic Golden Age was characterized by the importance placed on learning, leading to incredible achievements in the arts, sciences, and philosophy. With the great Baghdad House of Wisdom as the locus of intellectual development, great strides were made in the realms of medicine, astronomy, mathematics, and so much more. Numerous forms of education were on offer, such as in schools, libraries, and observatories.A Jew and a Muslim playing chess from El Libro de los Juegos, commissioned by Alphonse X of Castile, Madrid, 13th century. Source: Wikimedia CommonsGovernance during the Islamic Golden Age was based on Islamic religious and juridical principles. Islamic scholars carefully studied religious texts such as the Quran and the Hadiths to create the laws governing Islamic society. For instance, interest-free loans were provided for the poor, following Islamic principles condemning usury.Politics in the Muslim world was guided by a religiously informed vision of peace and justice. Outside of specifically Islamic influences, the philosophical underpinnings of Islamic political and social life were based above all on Greek philosophy and science, as well as Persian and Indian thought.Muslim imperial rule further allowed for a notable degree of cultural diversity within unity, distinguishing the Islamic world from the oppressive and suffocating Christian rule in Europe. The greater inclusivity of Muslim society was a central reason for the rapid advances made in the arts and sciences.Combat between a crusader soldier and a Muslim soldier, around 1250. Source: Radio FranceThe Islamic Golden Age suffered a slow decline as a result of the Crusades, the Mongol invasions, and a number of other political and economic factors. Eventually, Christian Europeans seized many Muslim territories, oftentimes through brutal means.Spain was conquered by the Christians at the end of the Spanish Reconquista in 1491. Amongst the Jewish communities forcefully expelled by newly Christianized Spain in 1492, a nostalgia for the much-preferable conditions of Muslim rule began to develop. This nostalgia was the original basis for the utopian conception of Jewish life during the Islamic Golden Age.The Utopian Conception of Jewish-Muslim RelationsThe Civilization of Cordoba in the Time of Abd-al-Rahman III, by Dionisio Baixeras Verdaguer, 1885. Source: University of BarcelonaModern historiographical studies of the lives of Jewish people during the Islamic Golden Age began in the early 19th century, led by the scholarship of Jewish historians. These scholars, living in the midst of horrific Western European antisemitism, dreamed of a world free of antisemitic violence and oppression. Taking cues from the previously expelled Jews of Spain, they found evidence that such a world is possible in their study of the Islamic Golden Age.These historians envisioned the Islamic Golden Age as a sort of utopia for Jewish people, relative to the horrors of the Christian West. In the Islamic Golden Age, they saw a model for widespread Jewish flourishing.According to these historians, the Muslim world during the Islamic Golden Age was uniquely tolerant of Jews and Jewish life as a whole. They cite the political and cultural achievements of Jews in the Muslim world, as well as evidence of widespread social integration, to make their point.Following the popularization of Zionism among historians in the 20th century, especially among Jewish historians, there was a tremendous backlash to the utopian conception forwarded by the early historians. These 20th and 21st-century scholars argued for a highly pessimistic view of Jewish life during the Islamic Golden Age the polar opposite of the utopian conception.The Pessimistic Conception of Jewish-Muslim RelationsTheodor Herzl At The First Zionist Congress in Basel, 1897. Source: Wikimedia CommonsDuring the 20th century, Jewish-Muslim relations steadily declined under the pressure of mass Zionist immigration to Palestine. Violence broke out between Jews and Muslims throughout the Middle East. Indigenous Jewish communities, such as those in Yemen, were increasingly persecuted by Muslims. Zionist settlers in Palestine stopped integrating into pre-existing communities and engaged in increasingly intense violence against their new majority-Muslim neighbors.In this context of ratcheting tensions between Jews and Muslims, some scholars began to argue for a pessimistic conception of Jewish life during the Islamic Golden Age. According to the pessimistic conception, Jewish life under Muslim rule was not unlike Jewish life under Christian rule: violently antisemitic and persecutory as a rule.Unsurprisingly, there is some truth in both the utopian and pessimistic conceptions of Jewish-Muslim relations during the Islamic Golden Age. Both, however, err too far in one direction or another. So, what did the reality look like?Jewish Legal Status During the Islamic Golden AgePage from a Manuscript on Islamic Law, Spain, 11th century. Source: Los Angeles County Museum of ArtThroughout the Islamic Golden Age, Jewish communities submitted to an overall condition of Muslim rule in exchange for protection against targeted persecution and oppression.Jews were allowed general cultural and political freedom, within some limitations, which were largely the same as the limitations imposed upon Christians. Both Jews and Christians, as non-Muslim monotheists, were legally categorized as dhimmi, a special legal category literally meaning protected person. Dhimmi were not subject to forced conversion, following the principle of non-compulsion laid out in the Quran (Sura 2:256). They were socially and territorially mobile.Unlike in the Christian world, dhimmi Jews were allowed to govern many of their own matters of religion, as well as family and personal matters, according to their own precepts. They could select many of their own leaders and jurists. For example, many Jewish communities maintained their own Rabbinical courts in order to adjudicate internal disputes.Some of the limitations imposed upon all dhimmi included prohibitions against constructing new religious sites, bans on public engagement in religious rituals, wearing clothing differentiating them from Muslims, and acknowledging Muslim rule. In these senses, Jews were discriminated against by the Muslim world, as were other dhimmi.However, these discriminatory practices did not amount to active, targeted persecution of the kind practiced throughout the Christian West. As other dhimmi were discriminated against in a similar manner, there was no specifically anti-Jewish intent behind the discrimination. Moreover, restrictions placed upon Jews were often ignored by local Muslim rulers. So long as Jewish communities did their duty as dhimmi, above all by paying special poll taxes and accepting Muslim superiority, many of the restrictions placed upon them were often relaxed.Jewish Intellectual and Cultural Life During the Islamic Golden AgeGreat Synagogue of Baghdad, Iraq. Source: Babylonian Jewry Heritage CenterThe mobility of Jews in the Islamic world created ideal conditions for the dissemination of Jewish culture on a much wider scale than seen anywhere else. Jewish communities could share cultural developments, exchange goods, and teach each other about unique beliefs and practices.Jews were increasingly urban throughout the Islamic Golden Age, with many moving to Baghdad. In Baghdad, two great rabbinic academies were established under Muslim rule as the centers of Jewish intellectual life. Jews from all throughout the Muslim world learned at the academies. Thousands of letters the academies sent to Jewish communitiesfrom the Mediterranean to North Africa to Spainare preserved to this day. The letters instructed Jewish communities on important matters of law and practice.Manuscript page by Maimonides, Judeo-Arabic language in Hebrew letters. Source: Wikimedia CommonsJews and Muslims commonly inhabited the same public spaces and lived side-by-side in harmony. Cross-cultural pollination between Jews and Muslims enriched the intellectual and cultural traditions of both. Jews in Baghdad, as well as other cosmopolitan centers of learning, such as Cordoba, worked in close conversation with their Muslim peers to advance the arts and sciences. Jewish thinkers developed everything from medicine to linguistics to poetry.They read and wrote in both Arabic and Hebrew, maintaining their own cultural tradition while not segregating themselves from the Muslim world around them. Arabic texts were frequently translated into Hebrew and vice-versa. For instance, the famed Jewish philosopher Maimonides was highly successful in Muslim Spain. He engaged heavily with both Hebrew and Arabic texts during his philosophical career. Thinkers such as Maimonides were accepted and honored by their Muslim peers.Jewish Economic Life During the Islamic Golden AgeA dirham of Caliph Al Mansur, 754-775 CE, photo by Jean Michel-Moullec. Source: FlickrJews in the Muslim world were full participants in economic life. They were allowed to engage in economic activities with few restrictions, in stark contrast to the Jews of Christian Europe. They commonly worked with Muslims and other non-Jews as equals, in a variety of industries.During the peak of the Islamic Golden Age, Jewish traders and merchants became heavily involved in economic life, especially in the great city of Baghdad. They were further integrated into the court of the Abbasid Dynasty in Baghdad, playing significant roles in commerce and economic administration.Other Jewish communities earned their livelihoods as everything from craftsmen to physicians to farmers to pharmacists. Many Jewish craftsmen were especially successful, producing goods for Muslims and non-Muslims alike.Jewish-Muslim economic integration helped Jewish communities maintain positive, mutually beneficial connections with Muslims. It allowed individual Jews to hold significant positions of power throughout the Muslim world and to access the wealth needed to live well.Jewish-Muslim Conflict During the Islamic Golden AgeInterior Courtyard of the Al-Hakim Mosque in Cairo, Egypt, Mosque named after the Caliph Al-Hakim, photo taken January 12, 2013. Source: Wikimedia CommonsJewish subjects of Muslim rule were rarely singled out and targeted by Muslims specifically as Jews. Most of the conflict between Jews and their Muslim sovereigns and neighbors resulted from Jews status as dhimmi.Some Muslims were suspicious of dhimmi. While dhimmi were far preferable to polytheists in the eyes of Islam, they still believed in corrupted versions of the truth and failed to accept the authority of the Prophet Muhammad. These facts led to varying degrees of distrust of dhimmi motives and actions among Muslims. However, this low-level interpersonal conflict was not universal and did not result in systematic persecution or oppression.Throughout the Islamic Golden Age, some individual Caliphs imposed limitations on Jews and other dhimmi participants in political life. Typically, these Caliphs attempted to unilaterally remove some or all dhimmi from public office. However, dhimmi were too critical to the successful administration of imperial power to be removed from all public offices, and they held significant positions of power throughout the Islamic Golden Age.Episodes of large-scale violence against Jews were exceedingly rare, but not unheard of. One 11th-century Muslim ruler, the Fatimid Caliph al-Hakim, destroyed a number of Jewish religious buildings and forcefully converted Jews in Egypt and Palestine to Islam. Another, lesser Muslim ruler attacked Jewish communities in Spain and North Africa before forcefully converting their inhabitants. Although these horrific episodes seriously harmed Jewish communities, they were not provoked by specifically anti-Jewish sentiment. Both also targeted Christians. Most infamously, Caliph al-Hakim ordered the total destruction of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and other Christian religious sites alongside Jewish ones.View of the 11th century (Zirid) walls of the Albacn district of Granada today, 2015. Source: Wikimedia CommonsThe most infamous occasion of Muslim persecution of Jews during the Islamic Golden Age was the Grenada massacre of 1066 CE. The massacre was instigated when an ambitious Jewish high official was accused of trying to overthrow the Muslim government in Granada from within. Other Grenadan Jews were suspected of being involved in the officials plot.One afternoon, after the accusation was made in public, a crowd of Muslims gathered together at the officials home. They murdered the official, then marched through the streets killing Jews and destroying Jewish property. Anti-Jewish riots and massacres sporadically occurred under similar circumstances elsewhere in the Muslim world.However, these outbursts of anti-Jewish violence and persecution were the exception, not the rule. The utopian conception of Jewish-Muslim relations during the Islamic Golden Age is an exaggeration, but it gets far closer to reality than the pessimistic conception. Jewish-Muslim relations throughout the Islamic Golden Age were overwhelmingly characterized by peaceful and prosperous co-existence within a culture of mutual acceptance and appreciation.0 Kommentare 0 Geteilt 14 Ansichten -

-