0 Comentários

0 Compartilhamentos

3KB Visualizações

Diretório

Elevate your Sngine platform to new levels with plugins from YubNub Digital Media!

-

Faça o login para curtir, compartilhar e comentar!

-

Our Best-Tested Garden Hose Is Expandable, 50 Feet Longer, and More Affordable Than Amazon’s Favorite ModelThe Best Garden Hose We Tested Is Longer and More Affordable Than Amazon’s Best-Seller If you click on links we provide, we may receive compensation. Our Best-Tested Garden Hose Is Expandable, 50 Feet Longer, and More Affordable Than Amazon’s Favorite Model Lightweight yet durable, the expandable hose is a space-saver—and it’s on sale. Published on May 31, 2025 05:00AM EDT Credit: Better...0 Comentários 0 Compartilhamentos 3KB Visualizações

-

New Elden Ring Nightreign mod already adds two-player co-op to the gameNew Elden Ring Nightreign mod already adds two-player co-op to the game As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases and other affiliate schemes. Learn more. While you can play Elden Ring Nightreign solo, Fromsoftware designed it as a three-player co-op experience. You're supposed to squad up with friends or...0 Comentários 0 Compartilhamentos 3KB Visualizações

-

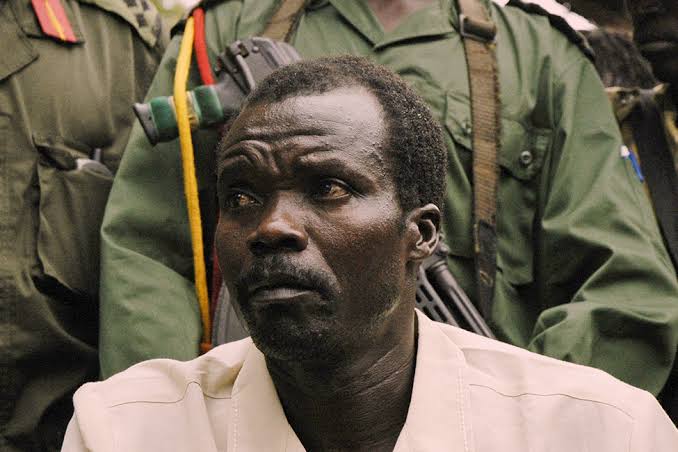

YUBNUB.NEWSWith Joseph Konys Trial To Begin in September, the Notorious Warlords Whereabouts Are a Mystery and Justice Remains ElusiveThirteen years ago, the viral Kony 2012 video by Invisible Children catapulted Ugandan warlord Joseph Kony into the Western spotlight, exposing the horrific crimes of his LRA through haunting footage0 Comentários 0 Compartilhamentos 191 Visualizações

YUBNUB.NEWSWith Joseph Konys Trial To Begin in September, the Notorious Warlords Whereabouts Are a Mystery and Justice Remains ElusiveThirteen years ago, the viral Kony 2012 video by Invisible Children catapulted Ugandan warlord Joseph Kony into the Western spotlight, exposing the horrific crimes of his LRA through haunting footage0 Comentários 0 Compartilhamentos 191 Visualizações -

YUBNUB.NEWSZelensky Casts Doubt on Russias Commitment to Peace Ahead of Istanbul TalksBy Blessing Nweke As fresh rounds of peace negotiations loom, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky has voiced deep skepticism over Russias intentions, accusing Moscow of sabotaging progress ahead0 Comentários 0 Compartilhamentos 190 Visualizações

YUBNUB.NEWSZelensky Casts Doubt on Russias Commitment to Peace Ahead of Istanbul TalksBy Blessing Nweke As fresh rounds of peace negotiations loom, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky has voiced deep skepticism over Russias intentions, accusing Moscow of sabotaging progress ahead0 Comentários 0 Compartilhamentos 190 Visualizações -

YUBNUB.NEWSAs Musk Steps Aside From DOGE, Trumps Budget Chief Steps Up To Carry OnCritical Cost-CuttingOn Wednesday evening, the worlds wealthiest man announced that his sojourn in the nations capital is almost over. As my scheduled time as a Special Government Employee comes to an end, I would0 Comentários 0 Compartilhamentos 194 Visualizações

YUBNUB.NEWSAs Musk Steps Aside From DOGE, Trumps Budget Chief Steps Up To Carry OnCritical Cost-CuttingOn Wednesday evening, the worlds wealthiest man announced that his sojourn in the nations capital is almost over. As my scheduled time as a Special Government Employee comes to an end, I would0 Comentários 0 Compartilhamentos 194 Visualizações -

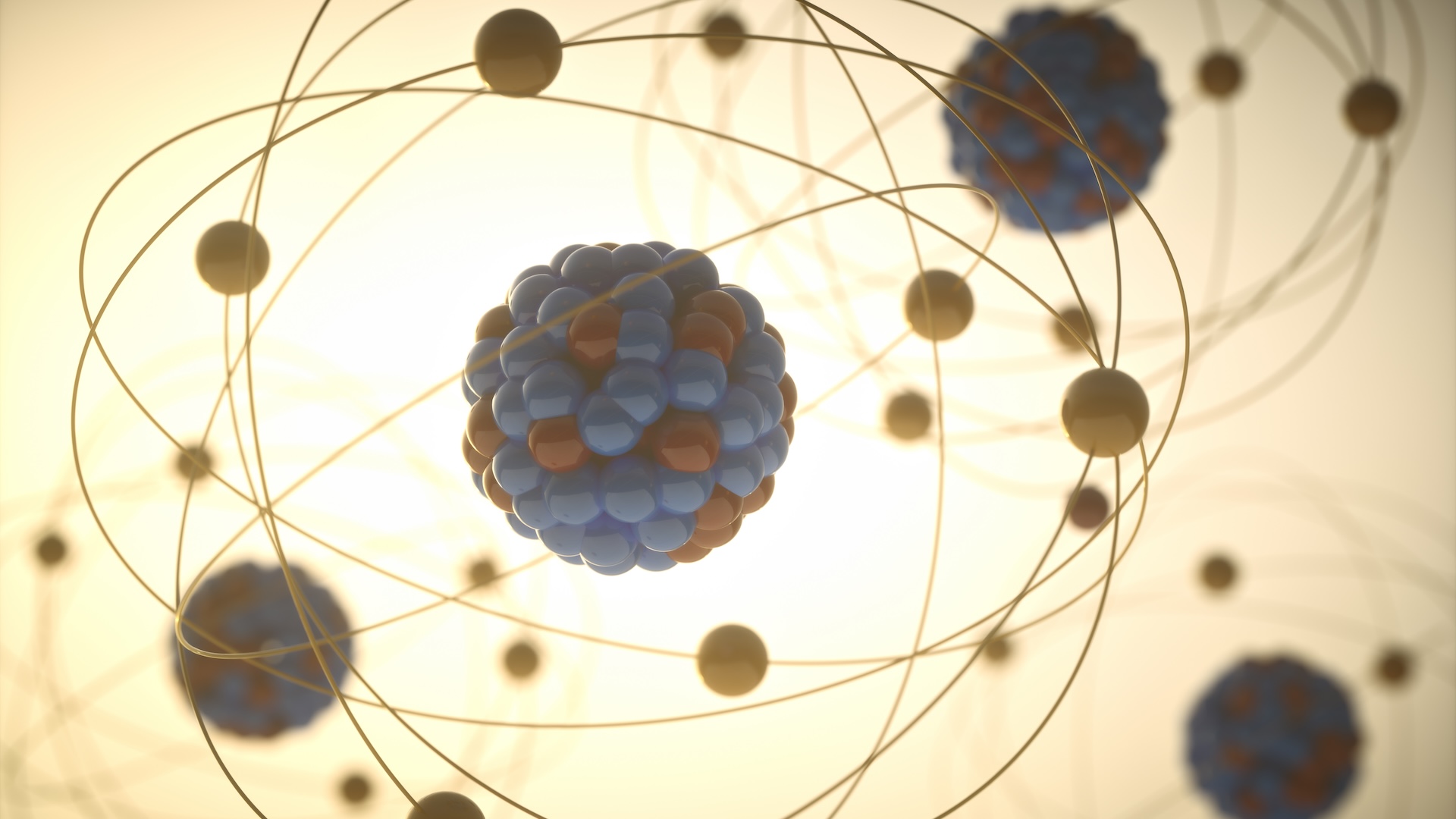

WWW.LIVESCIENCE.COMInfamous 'neutron lifetime puzzle' may finally have a solution but it involves invisible atomsA type of hydrogen that doesn't interact with light could explain how long neutrons live and reveal the identity of the universe's dark matter, according to a new theory.0 Comentários 0 Compartilhamentos 198 Visualizações

WWW.LIVESCIENCE.COMInfamous 'neutron lifetime puzzle' may finally have a solution but it involves invisible atomsA type of hydrogen that doesn't interact with light could explain how long neutrons live and reveal the identity of the universe's dark matter, according to a new theory.0 Comentários 0 Compartilhamentos 198 Visualizações -

WWW.THECOLLECTOR.COMGiuseppe Verdi: The Bard of the Risorgimento (Bio & Facts)On January 30, 1901, as a hearse drove the coffin of Giuseppe Verdi to the cemetery in Milan, a huge crowd gathered to honor the greatest 19th-century Italian composer. As the small funeral procession advanced through the city, the people waiting along the route began to sing the Va, pensiero (Fly, Thought) from the opera Nabucco. Also known as the Chorus of the Hebrew Slaves, the piece had become the unofficial anthem of the Risorgimento, the movement for Italian unification. Indeed, the lyrics of the chorus, intoned by the Jews longing for their lost homeland, resonated with the Italian patriots fighting to free the peninsula from foreign control.Giuseppe VerdiThe house in Roncole Busseto, now Roncole Verdi, where Giuseppe Verdi was born. Source: Parma WelcomeGiuseppe Verdi was born in 1813 in Roncole, a small village near Busseto, a rural town in the Duchy of Parma. Verdi, the son of an innkeeper, was a musically gifted child. At the age of nine, he was already playing the organ in the local church. His unusual talent captured the attention of Antonio Barezzi, a wealthy resident of Roncole and music enthusiast. Barezzi soon took young Verdi under his wing, sponsoring his musical studies.After spending some time in Milan, Giuseppe Verdi returned to Roncole, where he married Margherita Barezzi, the daughter of his patron, in 1836. Three years later, he finally made his operatic debut with Oberto, Conte di San Bonifacio, which premiered at the La Scala theater in Milan.The following year, however, the loss of his two young children and wife sent the composer into a depressive spiral. His career also suffered a step back. Then, in 1842, Verdis third operatic work, Nabucco, was a roaring success, turning the 28-year-old artist into a prominent Italian musician. In the 1840s, a period he dubbed his anni di galera (years of prison), Verdi composed more than 20 new operas in rapid succession, including Ernani, Macbeth, Attila, and I Lombardi alla prima crociata. At the end of the decade, his fame grew both in Italy and abroad, earning him commissions from France and England.Portrait of Giuseppina Strepponi by Karoly Gyurkovich. Source: Biblioteca Digitale Licei Musicali e CoreuticiIn 1859, Verdi married his long-time mistress, opera singer Giuseppina Strepponi. The couple had been living together in Busseto since 1849, provoking a scandal among the local community. In the 1850s, Verdis second wife performed in some of his most important operas, including La Traviata (The Fallen Woman). Based on La Dame aux camlias by Alexandre Dumas fils (son of the famed author Alexandre Dumas), the tragic story of the courtesan Violetta, along with Rigoletto (1851) and Il Trovatore (1853), cemented Verdis fame in Italy and abroad.During his prolific career, Verdi challenged the rules of operatic composition of his time, creating compelling and emotionally rich stories and characters. His ability to portray the complexity of human nature and ponder on topics such as power, love, and betrayal turned him into one of the most celebrated opera composers of the 19th century. Today, opera houses still regularly stage many of his pieces.In 1893, La Scala Theater produced Verdis final opera, Falstaff. Based on Shakespeares Merry Wives of Windsor and Henry IV, the composers comic work is a humorous and self-deprecating self-portrait and retrospective reflection on his life. Giuseppe Verdi died in Milan on January 27, 1901. Upon hearing of his death, the Italian Parliament lamented the loss of one of the highest expressions of the national genius.Giuseppe Verdi & the Italian OperaExterior of the La Scala theater in Milan. Source: Regione LombardiaWhen Giuseppe Verdi composed his first opera, the European music landscape was dominated by the German composer Richard Wagner, who posited the idea of the Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art). In Italy, the tradition of bel canto (beautiful singing), a style of singing featuring vocal ability and smooth melodies, mastered by Gaetano Donizetti and Gioacchino Rossini, was entering its final stage. In his works, Verdi began challenging the rigid rules of the bel canto, filling his operas with vigorous themes and dramatic scenes.At the beginning of the 19th century, the Italian peninsula, where a group of Florentine intellectuals had invented opera singing in the 16th century, was divided into several states and principalities controlled by different European powers. In 1814, Count Metternich scornfully remarked that Italy was only a geographical expression.In a territory lacking a national identity and even a common language, operas, whose productions were organized by theaters across the peninsula, provided a means to unite audiences otherwise separated by different customs and laws. In a sense, before being politically united, Italy had already been musically unified by opera.Portrait of Giuseppe Verdi. Source: Dallas Symphony OrchestraIn his 1836 essay La filosofia della musica (The Philosophy of Music), published in the magazine Litaliano, Giuseppe Mazzini emphasized the civic and social role of music. In particular, he focused on opera, a unique musical style he identified as intrinsically Italian. In this sense, the philosopher of the Risorgimento called for an Italian opera composer who would develop a national culture.The peculiar connection between opera and italianit (Italianness) also filled the diary entries of Austrian diplomat Joseph Alexander Hbner in 1848. Describing a demonstration in Milan, the count ironically commented: From three in the afternoon until eleven at night one could admire the strength of the lungs and the resonance of the throats of this populace. Each one seemed to have been born for the Opra.Va, pensiero: The Patriotic ChorusesHandwritten score of the Va, pensiero. Source: Corale Giacomo PucciniIn the mid-19th century, when the movement for Italian independence was well underway, Giuseppe Verdi seemed to embody the patriotic composer envisioned by Giuseppe Mazzini. According to a popular anecdote, during the premiere of Nabucco, the audience, defying the rigid rules introduced by the Austrians, demanded an encore of Va, pensiero, the chorus of the Hebrew slaves longing for their lost fatherland as they languished under the despotic rule of the Babylonian King Nebuchadnezzar.Fly, thought, on wings of gold Oh, my country, so beautiful and lost, sing the captives. While modern research has cast doubt on the veracity of the event, the link between the scene and the Italians patriotic struggle is evident.An 1853 map of Italy. Source: TreccaniGiuseppe Verdi was the first Italian composer to give the chorus a leading role in his operas. The impactful choral scenes, with the choir at the center of the stage to evocate lost homelands, became the leitmotiv of Verdis musical works. Commonly known as cori patriottici (patriotic choruses), they played a central role in establishing the image of Giuseppe Verdi as the Bard of the Risorgimento. Oppressed land of ours, mourn the Scottish refugees in the opening scene of the fourth act of Macbeth, you cannot have the sweet name of mother now that you have become a tomb for your sons.In the politically and emotionally charged environment of the Risorgimento, Verdis patriotic choruses seemed to garner the nationalist aspirations and ideals of the Italians in impactful scenes of spiritual unity, thus providing a visual representation of that national sentiment the Risorgimento activists strove to ignite throughout the peninsula. In this sense, Verdis choral moments, depicting a community of heroes liberating their homeland, were the embodiment of the patriotic dream about a nation one in arms, in language, in faith/In remembrance, in blood, and in heart, as evoked by Alessandro Mazzoni in his poem March 1821.Viva V.E.R.D.I.The slogan Viva VERDI handwritten on a wall. Source: Associazione Mazziniana ItalianaAlthough primarily set in the Middle Ages, Giuseppe Verdis operas, filled with revolts against oppression and tyranny, resonated with the contemporary audiences increasing frustration with authoritarian foreign control. As strict Austrian censorship prevented artists from openly referring to the present situation, retelling past events as paradigms for the independence movement became a common practice.The 1282 Sicilian successful rebellion against the Angevin rule, for example, became an emblem of the 19th-century patriotic struggle. The event, known as Vespri siciliani (Sicilian Vespers), inspired Giuseppe Verdi and the Italian painter Francesco Hayez. Oh thou, Palermo, land of my devotion, sang Giovanni da Procida in I Vespri Siciliani (1855), Summon thy pride from shameful emotion/In ancient glory once more to shine.The political messages hidden in Verdis compositions were not lost on the theatergoers. I remember, wrote Marco Marcelliano Marcello in Rivista contemporanea, with what marvelous avidity the populace of our Italian cities was seized by these broad and clear melodies, and with what agreement they walked singing.Similarly, the so-called Ernani hat, from Verdis 1844 opera with the same name, was popular among the Milanese rebels who took part in the 1848 uprising against the Habsburg Empire known as the Cinque giornate di Milano (Five Days of Milan).La battaglia di Legnano by Amos Cassioli, 1870. Source: Catalogo generale dei Beni CulturaliA true believer in the patriotic struggles, Verdi supported the 1848 revolt. Honour to these heroes, enthusiastically wrote the composer to Francesco Piave, one of the authors of his librettos, The hour of her liberation has sounded.While Verdi claimed that the music of the cannon was the only music welcome to the ears of Italians in 1848, he did not interrupt his musical activity.In Milan, Verdi was a frequent guest in the salon of Countess Clara Maffei, where he met several leading intellectuals and artists involved in the nationalist cause. In 1848, on Giuseppe Mazzinis suggestion, Giuseppe Verdi composed the patriotic song Suona la tromba (The Trumpet Sounds). Goffredo Mameli, the young author of the future Italian official hymn, The Song of the Italians, wrote the text.The following year, his La battaglia di Legnano, telling the conflict between Frederick Barbarossa (ruler of the Holy Roman Empire) and the Lombard League, premiered in Rome, where Mazzini had established the revolutionary Roman Republic, forcing Pope Pius IX to leave the city. In 1867, Verdi addressed the Roman Question (the clash between the Catholic Church and the Kingdom of Italy) with Don Carlo, where Philip II of Spain and the Grand Inquisitor battled over the control of the state.During the performance of La battaglia di Legnano, the audience allegedly shouted Long Live Italy and Long Live Verdi while the choir started singing the words Long Live Italy! A secret pact binds all her children.In the 1850s, the phrase Viva Verdi became a common refrain among Italian patriots. Written on walls and yelled during demonstrations and operatic performances, the slogan was the acrostic for Viva Vittorio Emanuele Re dItalia (Long Live Victor Emmanuel King of Italy). Thus, Giuseppe Verdi and his music became forever interwoven with the Risorgimento.Giuseppe Verdi Between Nation-Building & MythMonument of Giuseppe Verdi in Busseto. Source: Teatro Regio ParmaAfter the establishment of the Kingdom of Italy in 1861, prompted by Count Camillo Benso of Cavour (the first Italian Prime Minister), Giuseppe Verdi agreed to take an active role in politics. However, the composer was ill at ease in the political scene. As a result, he soon opted to leave his post as deputy to devote himself to his music. In 1874, King Victor Emmanuel II appointed him as a senator, thus officially acknowledging his prominent role during the patriotic struggle.By that time, Giuseppe Verdi was already venerated as a national monument. Indeed, the composer rivaled Giuseppe Garibaldi, the military hero of the Risorgimento, in popularity. Over the following centuries, his operas became an international emblem of italianit (Italianness). In 1946, after the end of World War II, the La Scala theater reopened with a concert featuring, among other pieces, the Chorus of the Hebrew Slaves. Arturo Toscanini, the anti-fascist Italian conductor, directed the orchestra and choir. In 2011, the 150th anniversary of the unification of Italy, Riccardo Muti also conducted a performance of Verdis most popular chorus. During the encore, the audience rose to their feet and sang along.Recently, some scholars have questioned the narrative claiming that Giuseppe Verdis operas played a key role in spreading the ideals of the Risorgimento throughout the peninsula. According to these scholars, the image of Verdi as father of the fatherland appeared later, when the new state was building founding myths. While the link between Verdi and the Risorgimento may have developed later than traditionally assumed, there is no denying the cultural impact of Verdi and his music on the process of national unification and nation-building.0 Comentários 0 Compartilhamentos 201 Visualizações

WWW.THECOLLECTOR.COMGiuseppe Verdi: The Bard of the Risorgimento (Bio & Facts)On January 30, 1901, as a hearse drove the coffin of Giuseppe Verdi to the cemetery in Milan, a huge crowd gathered to honor the greatest 19th-century Italian composer. As the small funeral procession advanced through the city, the people waiting along the route began to sing the Va, pensiero (Fly, Thought) from the opera Nabucco. Also known as the Chorus of the Hebrew Slaves, the piece had become the unofficial anthem of the Risorgimento, the movement for Italian unification. Indeed, the lyrics of the chorus, intoned by the Jews longing for their lost homeland, resonated with the Italian patriots fighting to free the peninsula from foreign control.Giuseppe VerdiThe house in Roncole Busseto, now Roncole Verdi, where Giuseppe Verdi was born. Source: Parma WelcomeGiuseppe Verdi was born in 1813 in Roncole, a small village near Busseto, a rural town in the Duchy of Parma. Verdi, the son of an innkeeper, was a musically gifted child. At the age of nine, he was already playing the organ in the local church. His unusual talent captured the attention of Antonio Barezzi, a wealthy resident of Roncole and music enthusiast. Barezzi soon took young Verdi under his wing, sponsoring his musical studies.After spending some time in Milan, Giuseppe Verdi returned to Roncole, where he married Margherita Barezzi, the daughter of his patron, in 1836. Three years later, he finally made his operatic debut with Oberto, Conte di San Bonifacio, which premiered at the La Scala theater in Milan.The following year, however, the loss of his two young children and wife sent the composer into a depressive spiral. His career also suffered a step back. Then, in 1842, Verdis third operatic work, Nabucco, was a roaring success, turning the 28-year-old artist into a prominent Italian musician. In the 1840s, a period he dubbed his anni di galera (years of prison), Verdi composed more than 20 new operas in rapid succession, including Ernani, Macbeth, Attila, and I Lombardi alla prima crociata. At the end of the decade, his fame grew both in Italy and abroad, earning him commissions from France and England.Portrait of Giuseppina Strepponi by Karoly Gyurkovich. Source: Biblioteca Digitale Licei Musicali e CoreuticiIn 1859, Verdi married his long-time mistress, opera singer Giuseppina Strepponi. The couple had been living together in Busseto since 1849, provoking a scandal among the local community. In the 1850s, Verdis second wife performed in some of his most important operas, including La Traviata (The Fallen Woman). Based on La Dame aux camlias by Alexandre Dumas fils (son of the famed author Alexandre Dumas), the tragic story of the courtesan Violetta, along with Rigoletto (1851) and Il Trovatore (1853), cemented Verdis fame in Italy and abroad.During his prolific career, Verdi challenged the rules of operatic composition of his time, creating compelling and emotionally rich stories and characters. His ability to portray the complexity of human nature and ponder on topics such as power, love, and betrayal turned him into one of the most celebrated opera composers of the 19th century. Today, opera houses still regularly stage many of his pieces.In 1893, La Scala Theater produced Verdis final opera, Falstaff. Based on Shakespeares Merry Wives of Windsor and Henry IV, the composers comic work is a humorous and self-deprecating self-portrait and retrospective reflection on his life. Giuseppe Verdi died in Milan on January 27, 1901. Upon hearing of his death, the Italian Parliament lamented the loss of one of the highest expressions of the national genius.Giuseppe Verdi & the Italian OperaExterior of the La Scala theater in Milan. Source: Regione LombardiaWhen Giuseppe Verdi composed his first opera, the European music landscape was dominated by the German composer Richard Wagner, who posited the idea of the Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art). In Italy, the tradition of bel canto (beautiful singing), a style of singing featuring vocal ability and smooth melodies, mastered by Gaetano Donizetti and Gioacchino Rossini, was entering its final stage. In his works, Verdi began challenging the rigid rules of the bel canto, filling his operas with vigorous themes and dramatic scenes.At the beginning of the 19th century, the Italian peninsula, where a group of Florentine intellectuals had invented opera singing in the 16th century, was divided into several states and principalities controlled by different European powers. In 1814, Count Metternich scornfully remarked that Italy was only a geographical expression.In a territory lacking a national identity and even a common language, operas, whose productions were organized by theaters across the peninsula, provided a means to unite audiences otherwise separated by different customs and laws. In a sense, before being politically united, Italy had already been musically unified by opera.Portrait of Giuseppe Verdi. Source: Dallas Symphony OrchestraIn his 1836 essay La filosofia della musica (The Philosophy of Music), published in the magazine Litaliano, Giuseppe Mazzini emphasized the civic and social role of music. In particular, he focused on opera, a unique musical style he identified as intrinsically Italian. In this sense, the philosopher of the Risorgimento called for an Italian opera composer who would develop a national culture.The peculiar connection between opera and italianit (Italianness) also filled the diary entries of Austrian diplomat Joseph Alexander Hbner in 1848. Describing a demonstration in Milan, the count ironically commented: From three in the afternoon until eleven at night one could admire the strength of the lungs and the resonance of the throats of this populace. Each one seemed to have been born for the Opra.Va, pensiero: The Patriotic ChorusesHandwritten score of the Va, pensiero. Source: Corale Giacomo PucciniIn the mid-19th century, when the movement for Italian independence was well underway, Giuseppe Verdi seemed to embody the patriotic composer envisioned by Giuseppe Mazzini. According to a popular anecdote, during the premiere of Nabucco, the audience, defying the rigid rules introduced by the Austrians, demanded an encore of Va, pensiero, the chorus of the Hebrew slaves longing for their lost fatherland as they languished under the despotic rule of the Babylonian King Nebuchadnezzar.Fly, thought, on wings of gold Oh, my country, so beautiful and lost, sing the captives. While modern research has cast doubt on the veracity of the event, the link between the scene and the Italians patriotic struggle is evident.An 1853 map of Italy. Source: TreccaniGiuseppe Verdi was the first Italian composer to give the chorus a leading role in his operas. The impactful choral scenes, with the choir at the center of the stage to evocate lost homelands, became the leitmotiv of Verdis musical works. Commonly known as cori patriottici (patriotic choruses), they played a central role in establishing the image of Giuseppe Verdi as the Bard of the Risorgimento. Oppressed land of ours, mourn the Scottish refugees in the opening scene of the fourth act of Macbeth, you cannot have the sweet name of mother now that you have become a tomb for your sons.In the politically and emotionally charged environment of the Risorgimento, Verdis patriotic choruses seemed to garner the nationalist aspirations and ideals of the Italians in impactful scenes of spiritual unity, thus providing a visual representation of that national sentiment the Risorgimento activists strove to ignite throughout the peninsula. In this sense, Verdis choral moments, depicting a community of heroes liberating their homeland, were the embodiment of the patriotic dream about a nation one in arms, in language, in faith/In remembrance, in blood, and in heart, as evoked by Alessandro Mazzoni in his poem March 1821.Viva V.E.R.D.I.The slogan Viva VERDI handwritten on a wall. Source: Associazione Mazziniana ItalianaAlthough primarily set in the Middle Ages, Giuseppe Verdis operas, filled with revolts against oppression and tyranny, resonated with the contemporary audiences increasing frustration with authoritarian foreign control. As strict Austrian censorship prevented artists from openly referring to the present situation, retelling past events as paradigms for the independence movement became a common practice.The 1282 Sicilian successful rebellion against the Angevin rule, for example, became an emblem of the 19th-century patriotic struggle. The event, known as Vespri siciliani (Sicilian Vespers), inspired Giuseppe Verdi and the Italian painter Francesco Hayez. Oh thou, Palermo, land of my devotion, sang Giovanni da Procida in I Vespri Siciliani (1855), Summon thy pride from shameful emotion/In ancient glory once more to shine.The political messages hidden in Verdis compositions were not lost on the theatergoers. I remember, wrote Marco Marcelliano Marcello in Rivista contemporanea, with what marvelous avidity the populace of our Italian cities was seized by these broad and clear melodies, and with what agreement they walked singing.Similarly, the so-called Ernani hat, from Verdis 1844 opera with the same name, was popular among the Milanese rebels who took part in the 1848 uprising against the Habsburg Empire known as the Cinque giornate di Milano (Five Days of Milan).La battaglia di Legnano by Amos Cassioli, 1870. Source: Catalogo generale dei Beni CulturaliA true believer in the patriotic struggles, Verdi supported the 1848 revolt. Honour to these heroes, enthusiastically wrote the composer to Francesco Piave, one of the authors of his librettos, The hour of her liberation has sounded.While Verdi claimed that the music of the cannon was the only music welcome to the ears of Italians in 1848, he did not interrupt his musical activity.In Milan, Verdi was a frequent guest in the salon of Countess Clara Maffei, where he met several leading intellectuals and artists involved in the nationalist cause. In 1848, on Giuseppe Mazzinis suggestion, Giuseppe Verdi composed the patriotic song Suona la tromba (The Trumpet Sounds). Goffredo Mameli, the young author of the future Italian official hymn, The Song of the Italians, wrote the text.The following year, his La battaglia di Legnano, telling the conflict between Frederick Barbarossa (ruler of the Holy Roman Empire) and the Lombard League, premiered in Rome, where Mazzini had established the revolutionary Roman Republic, forcing Pope Pius IX to leave the city. In 1867, Verdi addressed the Roman Question (the clash between the Catholic Church and the Kingdom of Italy) with Don Carlo, where Philip II of Spain and the Grand Inquisitor battled over the control of the state.During the performance of La battaglia di Legnano, the audience allegedly shouted Long Live Italy and Long Live Verdi while the choir started singing the words Long Live Italy! A secret pact binds all her children.In the 1850s, the phrase Viva Verdi became a common refrain among Italian patriots. Written on walls and yelled during demonstrations and operatic performances, the slogan was the acrostic for Viva Vittorio Emanuele Re dItalia (Long Live Victor Emmanuel King of Italy). Thus, Giuseppe Verdi and his music became forever interwoven with the Risorgimento.Giuseppe Verdi Between Nation-Building & MythMonument of Giuseppe Verdi in Busseto. Source: Teatro Regio ParmaAfter the establishment of the Kingdom of Italy in 1861, prompted by Count Camillo Benso of Cavour (the first Italian Prime Minister), Giuseppe Verdi agreed to take an active role in politics. However, the composer was ill at ease in the political scene. As a result, he soon opted to leave his post as deputy to devote himself to his music. In 1874, King Victor Emmanuel II appointed him as a senator, thus officially acknowledging his prominent role during the patriotic struggle.By that time, Giuseppe Verdi was already venerated as a national monument. Indeed, the composer rivaled Giuseppe Garibaldi, the military hero of the Risorgimento, in popularity. Over the following centuries, his operas became an international emblem of italianit (Italianness). In 1946, after the end of World War II, the La Scala theater reopened with a concert featuring, among other pieces, the Chorus of the Hebrew Slaves. Arturo Toscanini, the anti-fascist Italian conductor, directed the orchestra and choir. In 2011, the 150th anniversary of the unification of Italy, Riccardo Muti also conducted a performance of Verdis most popular chorus. During the encore, the audience rose to their feet and sang along.Recently, some scholars have questioned the narrative claiming that Giuseppe Verdis operas played a key role in spreading the ideals of the Risorgimento throughout the peninsula. According to these scholars, the image of Verdi as father of the fatherland appeared later, when the new state was building founding myths. While the link between Verdi and the Risorgimento may have developed later than traditionally assumed, there is no denying the cultural impact of Verdi and his music on the process of national unification and nation-building.0 Comentários 0 Compartilhamentos 201 Visualizações -

WWW.THECOLLECTOR.COMThe Year of the Six Emperors (238 CE): A Complete GuideHerodians History of the Roman Empire starts with the observation that in a period of 60 years, the Roman imperial power was held by more emperors than would seem possible in so short a time This is a preface to his history of Rome, from the death of the last good emperor, Marcus Aurelius, in 180 CE to the fateful year of the six emperors in 238 CE. The year marked a turning point in Roman history, as the Golden Age of imperial Rome was over, and the third-century crisis truly began.The Soldier Emperor: Maximinus ThraxPortrait bust of Severus Alexander, Roman, c. 230-235 CE. Source: Metropolitan Museum of ArtAt the start of the year 238 CE, the Roman Empire was at a low point. The reigning emperor, Maximinus Thrax, was considered to have a lowly background. He had not been a senator or even an equestrian, as the short-reigned Macrinus had been upon his accession in 217-8 CE. Instead, he was a professional soldier. He had the good fortune of being on campaign in Germania with the emperor Severus Alexander in 235 CE. Alexander was reportedly a good ruler but not an effective soldier. His army ran out of patience and confidence in the young man while campaigning against the Germanic tribes on the empires northern borders. Alexander was murdered, as was his ever-present mother, Julia Mammaea, and the army chose Maximinus as their new emperor.Silver denarius with Maximinus Thrax on the obverse and the emperor in military attire standing between two military standards on the reverse, Rome, 238 CE. Source: American Numismatic SocietyMaximinus was reputedly of colossal size. The ever-inventive Historia Augusta claims he was so big he used his wifes bracelets for rings and that he could knock a horses teeth with a single punch! But more importantly, he was a skilled soldier. His accession marked the advent of a new type of emperor: the soldier, or barrack, emperor, who would become increasingly common throughout the third century as Romes military circumstances deteriorated.Portrait bust of Maximinus Thrax, Roman, c. 235-238 CE. Source: Capitoline Museum, RomeAfter quashing a number of revolts against his authority in 235 CE, Maximinus set about concluding Alexanders campaign in Germania. He duly smashed the Alemanni and launched a new war deep into Germanic territory. His victories in the north earned him the title Germanicus Maximus. This also gave him the confidence to recognize his son Maximus as his heir to imperial power. Over the course of 235-6 CE, more campaigns were fought against both the Dacians and Sarmatians.Uprising in Africa: Gordian I and Gordian IIRoman amphitheater at Thysdrus, Tunisia, c. 3rd century CE. Source: Wikimedia CommonsThe Roman Empire in the early decades of the third century was vast, stretching from the fringes of Scotland in the north through to the edge of the Sahara in the south. Controlling such a great territory was one of the principal challenges faced by an emperor. Ideally, they would be able to call on a retinue of capable, loyal administrators, especially from among their own senatorial class. Maximinus Thrax, of course, was not a senator. It is perhaps unsurprising, therefore, that despite his popularity among his soldiers, he was not universally loved. His reign was perceived to be oppressive, and soon, discontent would erupt into violence.Portrait bust of Gordian III, Roman, c. 242-244 CE. Source: Muse du Louvre, ParisThe catalyst for the political turmoil was a landowners revolt in the North African city of Thysdrus. Known today as El Djem, the Tunisian city is famous for its spectacular amphitheater. The citys procurator, on the orders of Maximinus, had been orchestrating an extremely severe regime of taxation and fines. The procurators attempts to extort the wealthy reached a breaking point. A mob of residents formed. In the violence that ensued, the procurator was murdered. The residents of Thysdrus then rounded on the elderly senator, Gordian, and proclaimed him their emperor. Given his advanced age, Gordian was initially reluctant. He acquiesced on the condition that his son, Gordian II, be elevated with him.Silver denarius with Gordian I on the obverse and the togate emperor on the reverse, Rome, 238 CE. Source: British MuseumThe most striking detail of the provincial elevation of the Gordians was that they were recognized by the senate back in Rome. This can be taken as a clear indication of Maximinus unpopularity with the senators. However, not all were disloyal to the emperor. The governor of the neighboring African province of Numidia, Capelianus, was keen to strike against Gordian, not least because of a personal grudge against the usurper. Although he could only draw on the support of a single legion, the III Augusta, Capelianus forces were far more experienced and skillful than the militia that marched out to confront him.The Battle of Carthage in 238 CE was a disaster for the Gordians. The younger emperor, Gordian II, was killed in the fighting. Devastated by the loss of his son and in a desperate situation, Gordian I hanged himself. He became the first emperor since Otho, in the year of the four emperors in 69 CE, to have killed himself.A Misjudged March on Rome: The Siege of AquilaeaPortrait of Maximinus Thrax, Rome, c. 235-238 CE. Source: NY Carlsberg Glyptotek, CopenhagenBy now, it was the spring of 238 CE, and the empire had already been ruled by three emperors. The senate, however, decided to stick to their guns. With both the Gordians dead, it would have been prudent to mollify Maximinus. Instead, the senate ordered the deification of both Gordian I and II while also condemning Maximinus as a public enemy. Furious, Maximinus abandoned his winter camp at Sirmium and marched south. His plan was to smash the treacherous senate. But as he crossed into the Italian peninsula, he quickly ran into problems.Portrait of Maximus, son of Maximinus Thrax, Rome, c. 253-258 CE. Source: Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, CopenhagenThe emperor was unwilling to march past the city of Aquileia, fearing that the rebels there would harass his armies. Therefore he laid siege to the city, which proved protracted and abortive. The Aquileians had no intention of surrendering. According to Herodian, the resistance they put up was fierce, with Maximinus men doused in pitch and olive oil and suffering terrible burns. Disaffection grew, not helped by rumors that all of Italy was now united in arms against its emperor. Fear and panic now spread, compounding the poor morale from the abortive siege.In May 238 CE, a group of soldiers surprised Maximinus in his quarters, and he was slain, along with his son and heir, Maximus. Their corpses were mutilated, and their heads were sent to Rome, an event celebrated on a striking piece of creative numismatic graffiti. Once they arrived at the imperial capital, the heads of Maximinus Thrax and his sons were greeted by the senate and the new emperors.An Imperial Triumvirate: Pupienus, Balbinus, & Gordian IIISilver antoninianus with Pupienus on the obverse and hands of the imperial colleagues clasped on the reverse, Rome, 238 CE; with Silver antoninianus with Balbinus on the obverse and the same clasped hands on the reverse, Rome, 238 CE. Source: British MuseumHaving declared Maximinus a public enemy, the senate had also been quick to act to recognize a new emperor. Lacking any standout candidate and desperate to have any leadership to confront the advancing Maximinus, they elected two elderly senators, Marcus Clodius Pupienus Maximus and Decimus Caelius Calvinus Balbinus. These were emperors four and five of the turbulent year. Pupienus had served as consul iterum, for the second time, during the reign of Severus Alexander. Balbinus had enjoyed a similar honor in 213 CE, during the reign of Caracalla.Bust of Pupienus, Rome, 283 CE. Source: Capitoline Museum, Rome; Bust of Balbinus, Rome, 238 CE. Source: Hermitage Museum, St PetersburgBoth were entrenched members of the senatorial aristocracy. They were also, perhaps as a result of this, not a popular choice among the urban plebs in Rome. When they were presented to the populace of the imperial capital, the two new emperors may have imagined a slightly warmer reception. They were greeted by a mob who hurled stones at them! Consequently, to appease the mob, it was decided that the thirteen-year-old Gordian III, the grandson of Gordian I, would be nominated as the heir to power.Gordian Triumphant: End of the Year of Six EmperorsPortrait bust of Gordian III, photographed by Louise Laffon, 1863-1864. Source: Victoria and Albert MuseumAlthough he did not confront Maximinus in battle, since the former emperors soldiers had turned on their leader, Pupienus had been sent north from Rome by the senate to orchestrate the campaign against the emperor-turned-enemy. After Maximinus death in June, he accepted the surrender of the soldiers and pardoned them. He then returned to Rome, only to find that the unrest that had greeted his and Balbinus accession had not been quelled. Rome remained in uproar, with the elderly Balbinus unable to restore civility. Eventually, the presence of the two emperors seemed to calm the situation, but only temporarily.As the example of Maximinus had shown, the imperial populace respected an emperor who could command the armies and win great victories. It was this that had allowed him to occupy the position of Severus Alexander. It was his failure at Aquileia that cost him his life. Perhaps conscious of their initial unpopularity, Pupienus and Balbinus began to plan a joint campaign. Pupienus would campaign in the east, against the Parthians, and Balbinus to the north, against the Germanic tribes.Their plans would never come to fruition. The Praetorian Guards, which, over the course of the late second century, had grown accustomed to ensuring the emperors recognized their special privileges, grew tired of the old men who had been thrust into office by the senate alone. The guardsmen attacked Pupienus and Balbinus, seized them, and stripped them naked. The old men were then dragged through the streets of the capital. Robbed of their dignity and a pitiable sight, the praetorians executed the two emperors. Together, they had ruled for just 99 days.End of 238: A Looming CrisisSilver antoninianus with Gordian III on the obverse and Mars in military dress on the reverse, Rome, 242 CE. Source: British MuseumThe murder of Pupienus and Balbinus left just one emperor remaining, Gordian III. His reign would be bedeviled by the same political instability that had wracked the fateful year 238 CE. Africa, which had once propelled the Gordian family to prominence, now attempted to remove it from power. Fortunately for Gordian, the revolt of Sabinianus in 240 CE was quickly quashed.But there was to be no respite for the young emperor, and affairs external to the empire were also deteriorating at an alarming rate. In particular, the Sassanid dynasty, which had taken over the Parthians mantle as Romes imperial rivals in the east, was becoming aggressive once again. Gordians first foray against the Sassanids was successful, culminating in victory at the Battle of Resaena in 243 CE. The resulting optimism was to be short-lived. The second campaign, a retaliatory Roman invasion of Sassanid territory, was checked at Ctesiphon. In 244 CE, at the Battle of Misiche, Gordian was killed. He was just 19 years old.Although the specifics of Gordians death are unknown, it left the Romans in a precarious position. The new emperor, Philip, was forced to purchase peace. This confirmed Roman weakness for the Sassanids, and the eastern frontier would be a pressure point throughout the third century. And it was not the only one. In 238 CE, it was clear that chaos was looming as leaders were no longer made in Rome but by armies in the field. Combined, these pressures would lead Rome to the brink of collapse several times over the next 50 years.0 Comentários 0 Compartilhamentos 205 Visualizações

WWW.THECOLLECTOR.COMThe Year of the Six Emperors (238 CE): A Complete GuideHerodians History of the Roman Empire starts with the observation that in a period of 60 years, the Roman imperial power was held by more emperors than would seem possible in so short a time This is a preface to his history of Rome, from the death of the last good emperor, Marcus Aurelius, in 180 CE to the fateful year of the six emperors in 238 CE. The year marked a turning point in Roman history, as the Golden Age of imperial Rome was over, and the third-century crisis truly began.The Soldier Emperor: Maximinus ThraxPortrait bust of Severus Alexander, Roman, c. 230-235 CE. Source: Metropolitan Museum of ArtAt the start of the year 238 CE, the Roman Empire was at a low point. The reigning emperor, Maximinus Thrax, was considered to have a lowly background. He had not been a senator or even an equestrian, as the short-reigned Macrinus had been upon his accession in 217-8 CE. Instead, he was a professional soldier. He had the good fortune of being on campaign in Germania with the emperor Severus Alexander in 235 CE. Alexander was reportedly a good ruler but not an effective soldier. His army ran out of patience and confidence in the young man while campaigning against the Germanic tribes on the empires northern borders. Alexander was murdered, as was his ever-present mother, Julia Mammaea, and the army chose Maximinus as their new emperor.Silver denarius with Maximinus Thrax on the obverse and the emperor in military attire standing between two military standards on the reverse, Rome, 238 CE. Source: American Numismatic SocietyMaximinus was reputedly of colossal size. The ever-inventive Historia Augusta claims he was so big he used his wifes bracelets for rings and that he could knock a horses teeth with a single punch! But more importantly, he was a skilled soldier. His accession marked the advent of a new type of emperor: the soldier, or barrack, emperor, who would become increasingly common throughout the third century as Romes military circumstances deteriorated.Portrait bust of Maximinus Thrax, Roman, c. 235-238 CE. Source: Capitoline Museum, RomeAfter quashing a number of revolts against his authority in 235 CE, Maximinus set about concluding Alexanders campaign in Germania. He duly smashed the Alemanni and launched a new war deep into Germanic territory. His victories in the north earned him the title Germanicus Maximus. This also gave him the confidence to recognize his son Maximus as his heir to imperial power. Over the course of 235-6 CE, more campaigns were fought against both the Dacians and Sarmatians.Uprising in Africa: Gordian I and Gordian IIRoman amphitheater at Thysdrus, Tunisia, c. 3rd century CE. Source: Wikimedia CommonsThe Roman Empire in the early decades of the third century was vast, stretching from the fringes of Scotland in the north through to the edge of the Sahara in the south. Controlling such a great territory was one of the principal challenges faced by an emperor. Ideally, they would be able to call on a retinue of capable, loyal administrators, especially from among their own senatorial class. Maximinus Thrax, of course, was not a senator. It is perhaps unsurprising, therefore, that despite his popularity among his soldiers, he was not universally loved. His reign was perceived to be oppressive, and soon, discontent would erupt into violence.Portrait bust of Gordian III, Roman, c. 242-244 CE. Source: Muse du Louvre, ParisThe catalyst for the political turmoil was a landowners revolt in the North African city of Thysdrus. Known today as El Djem, the Tunisian city is famous for its spectacular amphitheater. The citys procurator, on the orders of Maximinus, had been orchestrating an extremely severe regime of taxation and fines. The procurators attempts to extort the wealthy reached a breaking point. A mob of residents formed. In the violence that ensued, the procurator was murdered. The residents of Thysdrus then rounded on the elderly senator, Gordian, and proclaimed him their emperor. Given his advanced age, Gordian was initially reluctant. He acquiesced on the condition that his son, Gordian II, be elevated with him.Silver denarius with Gordian I on the obverse and the togate emperor on the reverse, Rome, 238 CE. Source: British MuseumThe most striking detail of the provincial elevation of the Gordians was that they were recognized by the senate back in Rome. This can be taken as a clear indication of Maximinus unpopularity with the senators. However, not all were disloyal to the emperor. The governor of the neighboring African province of Numidia, Capelianus, was keen to strike against Gordian, not least because of a personal grudge against the usurper. Although he could only draw on the support of a single legion, the III Augusta, Capelianus forces were far more experienced and skillful than the militia that marched out to confront him.The Battle of Carthage in 238 CE was a disaster for the Gordians. The younger emperor, Gordian II, was killed in the fighting. Devastated by the loss of his son and in a desperate situation, Gordian I hanged himself. He became the first emperor since Otho, in the year of the four emperors in 69 CE, to have killed himself.A Misjudged March on Rome: The Siege of AquilaeaPortrait of Maximinus Thrax, Rome, c. 235-238 CE. Source: NY Carlsberg Glyptotek, CopenhagenBy now, it was the spring of 238 CE, and the empire had already been ruled by three emperors. The senate, however, decided to stick to their guns. With both the Gordians dead, it would have been prudent to mollify Maximinus. Instead, the senate ordered the deification of both Gordian I and II while also condemning Maximinus as a public enemy. Furious, Maximinus abandoned his winter camp at Sirmium and marched south. His plan was to smash the treacherous senate. But as he crossed into the Italian peninsula, he quickly ran into problems.Portrait of Maximus, son of Maximinus Thrax, Rome, c. 253-258 CE. Source: Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, CopenhagenThe emperor was unwilling to march past the city of Aquileia, fearing that the rebels there would harass his armies. Therefore he laid siege to the city, which proved protracted and abortive. The Aquileians had no intention of surrendering. According to Herodian, the resistance they put up was fierce, with Maximinus men doused in pitch and olive oil and suffering terrible burns. Disaffection grew, not helped by rumors that all of Italy was now united in arms against its emperor. Fear and panic now spread, compounding the poor morale from the abortive siege.In May 238 CE, a group of soldiers surprised Maximinus in his quarters, and he was slain, along with his son and heir, Maximus. Their corpses were mutilated, and their heads were sent to Rome, an event celebrated on a striking piece of creative numismatic graffiti. Once they arrived at the imperial capital, the heads of Maximinus Thrax and his sons were greeted by the senate and the new emperors.An Imperial Triumvirate: Pupienus, Balbinus, & Gordian IIISilver antoninianus with Pupienus on the obverse and hands of the imperial colleagues clasped on the reverse, Rome, 238 CE; with Silver antoninianus with Balbinus on the obverse and the same clasped hands on the reverse, Rome, 238 CE. Source: British MuseumHaving declared Maximinus a public enemy, the senate had also been quick to act to recognize a new emperor. Lacking any standout candidate and desperate to have any leadership to confront the advancing Maximinus, they elected two elderly senators, Marcus Clodius Pupienus Maximus and Decimus Caelius Calvinus Balbinus. These were emperors four and five of the turbulent year. Pupienus had served as consul iterum, for the second time, during the reign of Severus Alexander. Balbinus had enjoyed a similar honor in 213 CE, during the reign of Caracalla.Bust of Pupienus, Rome, 283 CE. Source: Capitoline Museum, Rome; Bust of Balbinus, Rome, 238 CE. Source: Hermitage Museum, St PetersburgBoth were entrenched members of the senatorial aristocracy. They were also, perhaps as a result of this, not a popular choice among the urban plebs in Rome. When they were presented to the populace of the imperial capital, the two new emperors may have imagined a slightly warmer reception. They were greeted by a mob who hurled stones at them! Consequently, to appease the mob, it was decided that the thirteen-year-old Gordian III, the grandson of Gordian I, would be nominated as the heir to power.Gordian Triumphant: End of the Year of Six EmperorsPortrait bust of Gordian III, photographed by Louise Laffon, 1863-1864. Source: Victoria and Albert MuseumAlthough he did not confront Maximinus in battle, since the former emperors soldiers had turned on their leader, Pupienus had been sent north from Rome by the senate to orchestrate the campaign against the emperor-turned-enemy. After Maximinus death in June, he accepted the surrender of the soldiers and pardoned them. He then returned to Rome, only to find that the unrest that had greeted his and Balbinus accession had not been quelled. Rome remained in uproar, with the elderly Balbinus unable to restore civility. Eventually, the presence of the two emperors seemed to calm the situation, but only temporarily.As the example of Maximinus had shown, the imperial populace respected an emperor who could command the armies and win great victories. It was this that had allowed him to occupy the position of Severus Alexander. It was his failure at Aquileia that cost him his life. Perhaps conscious of their initial unpopularity, Pupienus and Balbinus began to plan a joint campaign. Pupienus would campaign in the east, against the Parthians, and Balbinus to the north, against the Germanic tribes.Their plans would never come to fruition. The Praetorian Guards, which, over the course of the late second century, had grown accustomed to ensuring the emperors recognized their special privileges, grew tired of the old men who had been thrust into office by the senate alone. The guardsmen attacked Pupienus and Balbinus, seized them, and stripped them naked. The old men were then dragged through the streets of the capital. Robbed of their dignity and a pitiable sight, the praetorians executed the two emperors. Together, they had ruled for just 99 days.End of 238: A Looming CrisisSilver antoninianus with Gordian III on the obverse and Mars in military dress on the reverse, Rome, 242 CE. Source: British MuseumThe murder of Pupienus and Balbinus left just one emperor remaining, Gordian III. His reign would be bedeviled by the same political instability that had wracked the fateful year 238 CE. Africa, which had once propelled the Gordian family to prominence, now attempted to remove it from power. Fortunately for Gordian, the revolt of Sabinianus in 240 CE was quickly quashed.But there was to be no respite for the young emperor, and affairs external to the empire were also deteriorating at an alarming rate. In particular, the Sassanid dynasty, which had taken over the Parthians mantle as Romes imperial rivals in the east, was becoming aggressive once again. Gordians first foray against the Sassanids was successful, culminating in victory at the Battle of Resaena in 243 CE. The resulting optimism was to be short-lived. The second campaign, a retaliatory Roman invasion of Sassanid territory, was checked at Ctesiphon. In 244 CE, at the Battle of Misiche, Gordian was killed. He was just 19 years old.Although the specifics of Gordians death are unknown, it left the Romans in a precarious position. The new emperor, Philip, was forced to purchase peace. This confirmed Roman weakness for the Sassanids, and the eastern frontier would be a pressure point throughout the third century. And it was not the only one. In 238 CE, it was clear that chaos was looming as leaders were no longer made in Rome but by armies in the field. Combined, these pressures would lead Rome to the brink of collapse several times over the next 50 years.0 Comentários 0 Compartilhamentos 205 Visualizações -

WWW.THECOLLECTOR.COM3 Fun Facts About the Iconic Ciniselli CircusLike most Victorian-era circuses, the Ciniselli Circus represented a space where rich and poor could enjoy a good show. In Imperial Russia, aristocrats gazed from balconies while the working class crowded the stalls below. While historic circuses remain problematic due to race, ableism, and animal rights issues, they offered a melting pot where society mixed. As the Ciniselli Circus gained popularity, its diverse acts allowed women and people of color to take center stage. The circus also helped break down social barriers and pave the way for revolution in Russia.1. It Was Founded by a Famous Italian PerformerGaetano Ciniselli by Charles Bergamasco, 1870; Gaetanos daughter, Emma Ciniselli. Source: Library of Congress and Wikimedia CommonsThe Ciniselli Circus started with a bold solo that evolved into a family act.Born in Milan, Italy, Gaetano Ciniselli (1815-1881) joined a circus by the age of twelve. Ambitious and talented, Gaetano trained with horses at the Francois Bauchers equestrian school in Paris. At the time, the circus was horse-centric. Gaetano became a horse whisperer, able to perform exotic acts on horseback with ease. Soon, his European tours expanded to Paris.But Gaetano knew he needed more than grit and skill to achieve his goals. He wanted to become a master of the arena.The best way to secure this was to make a lucky marriage.Fortunately, Gaetanos career put him in the path of Wilhelmina Ginne (1817-1886), a beautiful and celebrated horsewoman who came from a famous and wealthy circus family. Nicknamed Landrinette, after the Landrin lollipops popular at the time, Wilhelminas beauty and skill meant that wealthy admirers flocked to see her. They showered her with gifts, bouquets, and poems. But when it came time to marry, Wilhelmina chose her handsome horse master.This advantageous marriage opened a world of connections and opportunities to Gaetano. It also gave him access to Wilhelminas famous family, including her influential brother, Karl Magnus Ginne. A rich and powerful circus manager, Ginne had made a name for the family as one of the most famous troupes in Western and Eastern Europe. Ginne made sure his sisters married into other prominent circus dynasties.Cinisellis wife, Wilhelmina Ginne, was a famous equestrian performer noted for her beauty and wealthy family. Source: The Kazan CircusA celebrated entrepreneur, Gaetano decided to create his own troupe in London. It was not hard to find performers. His wifes three sisters, their husbands, and even Karl Ginne, his influential brother-in-law, joined the enterprise.London proved a huge success. Audiences crowded the stalls as Gaetano showed off his skills as one of the best equestrians and horse trainers in Europe and as a circus manager. He continued to perform acrobatics on horseback to the delight of audiences across the continent. He also charged expensive rates for private riding lessons which earned him a fortune.By the 1860s, Gaetano and his family made such a splash that Victor Emmanuel II, the first King of united Italy, invited him to train at the royal stables. At the time, Italy was experiencing the Risorgimentothe unification of separate principalities into a single nation-state. Ciniselli received the title Honorary Royal Horse-master. It was a title he treasured for the rest of his life. Years later, he printed it in large letters across his circus posters.In 1868, an appreciative monarch also bestowed the Order of the Crown of Italy on Gaetano. The man who came from nothing now boasted a personal coat of arms.As Cinisellis status grew, he wanted more.Giniselli first visited Russia in 1846 on the invitation of his old teacher, Alexander Guerra. Two French circus managers had built rival wooden circuses nearby, and Guerra needed a new act to beat out his competition. Whenever a circus troupe became famous in Paris or Berlin, the Russian state invited the performers to Russia. During that winter, the circus performed to the publics delight. However, the circus went bankrupt the following year, so Guerra and Ciniselli returned to Western Europe.Stunning equestrian acts and feats of horsemanship became a central part of the Ciniselli Circus programs. Source: Library of CongressBy 1869, heaped with honors from the King of Italy, Ciniselli returned to Russia. His brother-in-law, Karl Ginne, had established several wooden circuses there, including one in Moscow and another on St. Petersburgs Mikhailovskaya (later Manezhnaya) Square.For years, Ginne begged the authorities to lease a space near Engineers Square to build a permanent stone circus. Every time, the authorities turned him down. Ginnes wooden building, cold, ugly, and a fire hazard, failed to attract large crowds. As a last resort, Ginne asked Ciniselli to come and upgrade the enterprise.A traveling circus tradition has existed in Russia since the early days of the Rus. In the early 18th century, Peter the Great encouraged Western circuses. By 1724, every post station in St. Petersburg carried an order signed by the tsar announcing and protecting the arrival of foreign circus artists. After this, the circus became a growing form of popular entertainment.Many people, including the Russian authorities, felt surprised that Gaetano would abandon tours in Paris to move to St. Petersburg. In fact, the troupe broke its Paris contract to make the move. If Gaetano ever set foot on French soil, he would have to pay an enormous fine. This meant that Ciniselli and his troupe could never perform in Paris again. The Ciniselli family, accompanied by their adult children, Andrea, Ernest, Scipione, and Emma, arrived in the Russian capital.The move may have seemed far-fetched, but Gaetano dreamed of owning his own permanent circus. Russia represented an opportunity to make his dreams come true. No permanent stone circus existed in the Russian Empire. Circus, as a developing public art form, remained in a traveling format, interspersed with a few temporary wooden buildings knocked together.Ciniselli decided to change that.2. It Was Known as the Most Beautiful Circus in EuropeExterior of the Ciniselli Circus. Source: Library of CongressWhen Ciniselli decided to build the first stone circus in Russia, he set his sights on the same plot of land near Engineers Square, right on the Fontanka Embankment, that Ginne unsuccessfully tried to snag. The authorities kept rejecting the proposal because building the stables for the circus would mean closing off the walkway for the Mikhailovsky Castle, reducing foot traffic into the nearby Summer Gardens.Gaetano knew he needed a great sales pitch.In 1875, he turned to the City Duma. First, he appealed to Russias competitive spirit and desire to attain the same cultural status as other European cities. In the West, Ciniselli pointed out, every famous city had at least one permanent circus. Despite its cultural sites, large population, and status as an imperial capital, St Petersburg had no similar circus.Next, Gaetano, who had done his research, argued that Moscow, Warsaw, and other major Russian cities already had stationary circuses. The cities even subsidized their construction. Finally, the circus manager dangled the promise of a significant economic upturn. He observed that a troupe of 150 performers with 200 horses arriving in the city would stimulate a thriving trade. Both the horses and people needed to eat. They would buy products. Shops would flourish. Even the working class would benefit by taking on jobs at the circus.Ciniselli added a bonus offer.Late nineteenth-century crimson and gold interior of the Ciniselli Circus. Source: Library of CongressAs a favor, he would demolish his brother-in-laws wooden circus on Mikhailovsky Square, build a park on the premises, and surround it with a wrought iron fence. He would even throw in a fountain. Best of all, he would use his own money to do it. In return, all the authorities needed to do was grant him permission to build near Engineers Square.As a parting shot, Ciniselli asked if they wanted to be like Paris. This appeal hit its mark in a country where most of the nobility spoke French more often than Russian. This blend of cultural competition and economic promise proved too good to pass up. The City Duma granted Cinisellis request to start breaking ground near Engineers Square.The building went up fast. It only took two years. According to a 19th-century travel guide, it also cost a staggering 40,625, or over $7,697,969 US dollars today (John M. Ross, The Globe Encyclopedia, vol. 5, 362).On December 26, 1877, the first stone circus building opened in Russia. Its exterior blended classical and baroque designs finished with bas-relief sculptures and figures of the muses standing in the arched windows. It was crowned by a giant mesh-ribbed dome to amplify the sound, which had the distinction of being the biggest circus dome of the 19th century.Pre-revolutionary view of the grand interior of the Ciniselli Circus showcasing the orchestra, stage, and imperial box, by A. Otsup, 1904-1914; Ciniselli Circus program. Source: Antenna Daily and 47News.The interior offered a study in luxury. Rich crimson velvet armchairs lined balconies decked with glittering gold, crystal, and mirrors. Caryatids flanked the draped royal box. Gas chandeliers dangled from the ceiling to light up the vast floor below. Soft Persian carpets sank underfoot. When the audience entered, they glimpsed exotic fish swimming in tanks built into the walls. The dome, designed to look like a circus big top, featured paintings of flowers and equestrian scenes of Ciniselli and his daughter, Emma. During the intermission, spectators peeked into the circus stables filled with 25 of the troupes 200 horses. Even the stables shone with marble and mirrors.Mindful of the fires that destroyed earlier circuses, Cinisellis Circus complied with all current fire codes to optimize safety, including cutting-edge emergency fire exits.The circus lavish interior catered to the upper crust of St. Petersburg society, although the circus appealed to all cultural levels. In fact, the Romanov family was so impressed by the design that they gave the architect Vasily Kenel a valuable diamond ring.While the boxes and stalls could seat 1,500 spectators, the standing gallery enabled the auditorium to fit up to 5,000 people. This meant that Ciniselli could pack the place, night after night, at full priceand he did. Getting a seat at the Ciniselli Circus could be competitive since tickets sold out a year in advance.Within a few years, the Ciniselli Circus became known as the most beautiful circus in Europe.3. Women and People of Color Took Center StageVisitors to the Ciniselli Circus watched dramatic shows such as stormy water spectacles that involved elaborate stage sets. Source: Library of CongressIn wintertime, the Ciniselli Circus came into its own.With St. Petersburgs streets shrouded in snow, the circus offered winter spectaculars blazing with light, color, and energy. Many visitors would hire a troika with three horses to navigate winter streets for a night at the circus.Armies complete with horses and foot soldiers marched and fought mock battles on stage. A water show called the Four Elements offered a favorite extravaganza that delighted audiences again and again. For this spectacle, Ciniselli transformed the arena into a giant pool where horses, deer, and elephants frolicked with their riders. Water cascaded from multiple fountains. Ciniselli also threw opera-style productions of Oedipus and the Three Women of Mikado.The circus remained a favorite with Russian leaders, both the tsars and later Soviet rulers. In March 1884, the future Nicholas II enjoyed a day at the circus. After breakfast, went to Cinisellis and watched the clowns various performances, he wrote in his diary, Everything was excellent; the clowns made us laugh terrifically.Emma Ciniselli; Cinselli Circus corps de ballet. Source: Wikimedia Commons and Marina Mayatskaya via Kazan CircusFamous riders and clowns competed onstage. In 1898, the World Wrestling Championship, featuring the Russian Lion, George Hackenschmidt, opened a session of the Ciniselli Circus.While the Ciniselli Circus stayed horse-centric, it also included nimble pole vaulters, wire-free dancers, a troupe of clowns, strong men, and a female ballet corps. Best of all, they never let the repertoire grow dull or repetitive.As a master of advertising and entertainment, Ciniselli changed the program daily, but kept a single act running two nights in a row if it made the public go wild. The Ciniselli family understood that the public quickly tired of the same shows over and over again and sought to infuse the circus with new life.Ciniselli Circus poster showing a female equestrian and clowns; 19th century circus programs often featured exotic spectacles that involved stereotyped images and animal acts that would not pass today but enthralled audiences at the time. Source: Kazan Circus and 47NewsThe Liberty Act turned into one of Scipiones most popular shows. In this act, the circus manager directed twelve free horses. This meant that no one restrained the horses by reins, saddles, or spurs Instead, the dozen horses performed synchronized movements just by verbal command.During these equestrian spectacles, the Ciniselli daughters pranced into the center of the arena. Like their mother, they demonstrated skills and confidence atop a horse.Liberty Act by Vasily Aleksandrovich Kenel, 1877. Source: Library of CongressIn a time and place where society often required women to adhere to strict behavioral standards, the circus offered an arena for those who did not fit into societys box to showcase their personalities and talents. Everyone applauded these shows, from the peasants to the tsar.Many Africans and people of African descent also found work at the Ciniselli Circus as talented acrobats, gymnasts, and troupe members. In contrast to the systemic racism of Jim Crow laws in America, people of color often found Russia a haven from racial prejudices. New performers regularly arrived by ship, fresh from shows at far-off places like the London Hippodrome.Ciniselli devoted his life and career to improving the quality of circus art. By the end of the 19th century, he significantly increased the circus prestige.The Ciniselli Circus today; Elephant act rehearsal at the Ciniselli Circus, c. 1910-1914. Source: Kazan CircusJust four years after opening his own circus, Gaetano Ciniselli died in 1881.His wife took over running the successful circus. When Wilhelmina passed, her oldest son, Andrea, became manager. Later, Scipione took over as circus manager. He brought new water acts and equestrian tricks to the program.The circus evolved as a political tool during the First World War. Popular singers gave 163 patriotic concerts to a diverse crowd from the Ciniselli Circus stage (Melissa Stockdale, Mobilizing the Russian Nation, 131). Workers flocked to performances, thanks to a special discount (Jahn Hubertus, Patriotic Culture in Russia, 116).As Russia headed toward revolution, the circus found itself on the brink of a new era. In 1919, the Soviet government nationalized the Ciniselli Circus and evicted the Ciniselli family. Scipione fled the country to Western Europe, where he died in poverty. His four nephews stayed and kept performing in acts all over the country. In the aftermath, a new group of artists took over running the circus to comply with the patriotic values of the new Soviet state. Emma Ciniselli married clown and juggler Nicholas Kiss. Together, they began a new circus dynasty.Emma Cinsinelli. Source: Society of Swedish Literature in FinlandIn 1924, the Soviets renamed it the Leningrad Circus (Miriam Neirick, When Pigs Could Fly and Bears Could Dance, 10). In 2015, it became the Ciniselli Circus once again. The park Ciniselli developed on Manezhnaya Square in exchange for permission to build the first stone circus became a cultural heritage site. The Ciniselli Circus remains an important cultural icon today.Many early circuses had a dark history of exploiting otherness, from race and gender to ableness. While the practices of historic circuses are challenging to modern values and the Russian circus did not escape stereotypes of the time, the Ciniselli Circus also offered a space for women and people of color to overcome many political and cultural barriers by appearing on stage.Toward the end of the Russian Empire, the Ciniselli Circus set a strong precedent for female participation in circus management. It also enabled people of color to take center stage instead of appearing only in sideshows. In the years before the Russian Revolutions of 1917, the circus universal appeal and accessibility widened cracks in the social system as classes mingled.Street art became accepted as an elevated form of entertainment, setting the stage for the circus prestige in the 20th century and beyond.Further ReadingClay, Catrine. (2006). King, Kaiser, Tsar. John Murray.Hubertus, Jan. (1995). Patriotic Culture in Russia During World War I. Cornell University Press.Neirick, Miriam. (2012). When Pigs Could Fly and Bears Could Dance: A History of the SovietCircus. University of Wisconsin Press.Ross, John M., ed. (1879). The Globe Encyclopedia of Universal Information. Vol. V. Estes &Lauriet.Stockdale, Melissa Kirschke. (2016). Mobilizing the Russian Nation: Patriotism and Citizenship in the First World War. Cambridge University Press.0 Comentários 0 Compartilhamentos 198 Visualizações