WWW.THECOLLECTOR.COM

How Did Gunpowder Change Warfare?

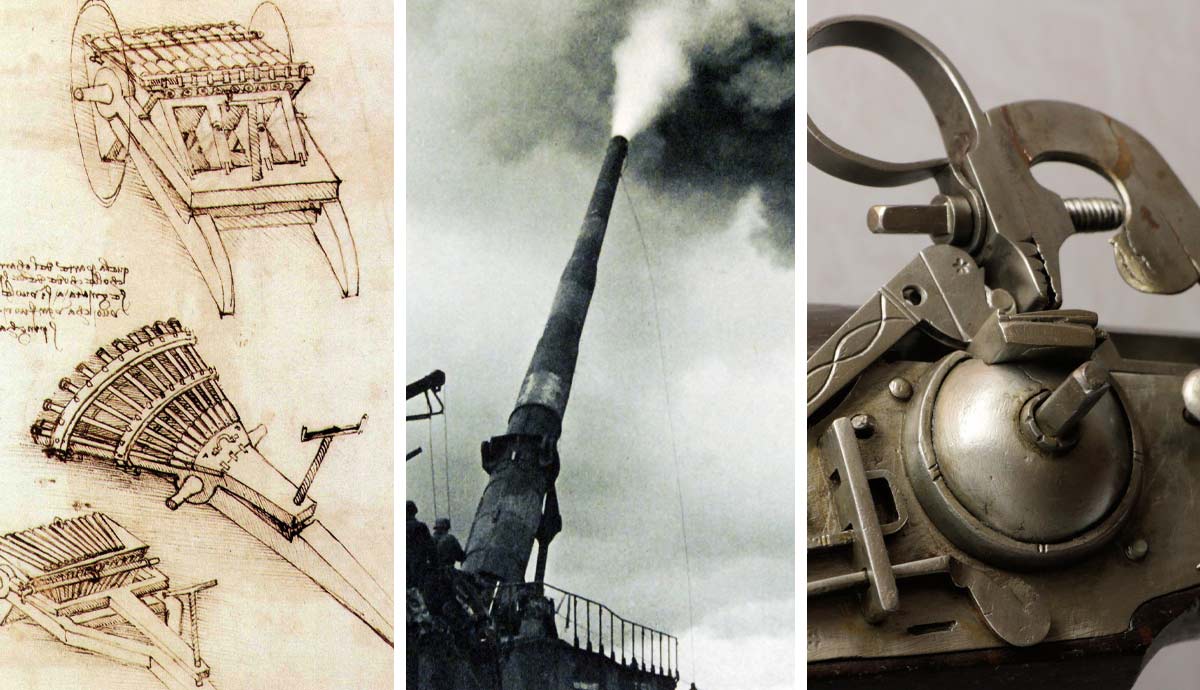

One of the most impactful inventions throughout all of human history, gunpowder changed the course of warfare. From fire arrows in China to propelling deadly munitions in the modern era, gunpowder shaped how conflicts were fought, guiding the evolution of warfare.What is gunpowder, and how did it change the way wars were fought?Gunpowder in Oriental WarfareKorean rocket arrows, photograph by Kai Hendry. Source: Wikimedia Commons/ FlickrToday, the term gunpowder refers to any number of powdered mixtures with a low-explosive yield that are used to propel projectiles from guns or used in the mining industry as a blasting agent. The traditional black powder, a saltpeter (potassium nitrate)-sulfur-charcoal mix, has largely been replaced in weaponry by smokeless powder, which is still referred to as gunpowder in common parlance.Gunpowder was likely the first explosive ever to be invented. It is said to have been invented in China during the Tang dynasty around the 9th century. However, there is evidence to suggest experiments with the gunpowder ingredients took place several centuries earlier. In the first millennium CE, alchemical experiments involving sulfur and saltpeter led to the creation of the explosive substance that would transform the world.As a work of art, Zo Sheehan Saldaa contextualizes the ingredients for black powder, sulfur, charcoal, and potassium nitrate (saltpeter). Source: The Aldrich Contemporary Art MuseumThe first usage of gunpowder in war comes from a vague reference in the early 10th century, which is thought to refer to fire arrows. Early gunpowder did not contain enough saltpeter to be explosive, but it was highly flammable in the open air. It is suggested that gunpowder was applied to arrows, which would ignite due to the rush of air when loosed.According to traditional texts from the 14th century, a variant of these arrows was able to use gunpowder as a propellant, essentially creating the first rocket. There is also mention of a variety of bombs being used. It was, however, an invention called the fire lance that began the evolution of the gun.Although not an actual gun, the fire lance was an evolutionary predecessor for which the first use in warfare is dated to the 12th century. It consisted of a bamboo tube containing gunpowder that would ignite via a slow match. Once ignited, the flames would spew from the front of the tube, along with any other objects that were placed inside. Such a weapon had a very short effective range of only a few feet. The design was adopted in Europe, where wooden tubes were initially used.Found in the water well of the destroyed Tannenberg Castle, The Tannenberg handgonne from 1399 is Germanys oldest surviving firearm, photograph by Oliver H. Source: Wikimedia Commons/Germanisches Nationalmuseum, NurembergBy the late 13th century, actual guns had been invented. Construction involved cast iron or bronze, and these weapons and concepts quickly made their way westward.Ultimately, gunpowder had a significant effect on Chinese warfare. It gave the Song dynasty a powerful edge that allowed it to defeat its enemies, including resisting Mongol invasions. The explosive power also allowed for the breaching of stone walls, revolutionizing warfare and enabling the Chinese to effectively capture enemy fortifications.The technology, however, was not easy to keep secret. The technology spread, and the Song advantage disappeared. The Mongols were able to employ gunpowder weapons to equally devastating effect.One of the most significant factors of gunpowder being used on the battlefield was its psychological effect on troops. Faced with fiery explosions and whizzing, chemical-propelled arrows, soldiers had to have nerves of steel.The First Guns in EuropeAn English wrought-iron bombard, photograph by ian262, ca. 1450. Source: Wikimedia Commons/FlickrThe rise of guns in Europe was not immediate but rather a slow process of experimentation and integration. Bow technology in the continent was highly advanced, with longbows and crossbows proving to be highly effective on medieval battlefields. In the 14th century, guns were being made for use in the fields, but their effectiveness was limited. The Hundred Years War, fought in France, was a major instance where this development occurred.Ranged combat on the battlefields during this era was primarily done through bows. The slow reload time of guns could not compete with the quick and effective volleys of English longbowmen. Even the slower crossbows, used en masse, were highly effective (except when the strings got wet, like at the Battle of Crcy).There is debate over whether the bodkin arrows used by the English could actually penetrate the plate armor used by French knights. While some academics deny this ability, computer analysis at Warsaw University in 2017 showed that this weapon could indeed penetrate plate armor at the time. Whatever the case, the effect arrows had, even with blunt force, wore down knights subjected to the intense volleys. Arrows could, without a doubt, penetrate light armor and unarmored horses. As such, the longbow remained the star of the show for the English during the Hundred Years War.Leonardo da Vincis 15th-century study of ribauldequins. Source: Wikimedia CommonsGuns, however, did make an impression as artillery, although not in any quantity enough to change the course of the earlier battles. In 1333, the English likely used cannons to supplement their other siege equipment at Berwick against the Scots. Historian Ranald Nicholson states that Berwick was probably the first town in the British Isles to be subjected to bombardment by cannon.Against the French at Crcy in 1346, the English used an unknown number of artillery pieces. These included ribauldequins and bombards. Ribauldequin were multi-barrelled organ guns, and bombards were early forms of cannon. Florentine Giovanni Villani recounted how, after the Battle of Crcy, the whole plain was covered by men struck down by arrows and cannon balls. The artillery was likely more impressive due to its loudness and fury rather than by its kill count. The extremely slow reload times meant these weapons must have fired very few times during the battle.The French used artillery, too, and at the Battle of Formigny in 1450, they employed two small culverins (early iterations of a cannon) to devastating effect, inflicting many casualties among the English bowmen. The final battle of the Hundred Years War was the Battle of Castillon in 1453, which proved the effectiveness of handgonnes. The battle saw the English ripped to shreds by field artillery.An elaborate 16th-century cannon, photograph by Alf van Beem. Source: Wikimedia Commons/Royal Danish Arsenal Museum, CopenhagenOver the decades, cannons replaced other siege weapons, such as the trebuchet. The ability of heavy stone balls projected by gunpowder to destroy fortification walls was unmatched. Cannons would evolve into far more elaborate and effective systems over the decades and centuries that followed, eventually culminating in the advanced artillery systems used today.Early artillery pieces were hazardous, not just to anyone they were aimed at but also to those operating them. They could split or even explode upon firing, causing injury and death. As time went by, building guns became more sophisticated, and the weapons became safer for their operators and deadlier to their enemies.Gunpowder Weapons EvolveA recreation of a pike and shot formation in action, photograph by Kweniston, 2008. Source: Wikimedia CommonsEarly personal firearms lacked buttstocks and triggers and had to be held under the arm, making them highly inaccurate. In the second half of the 15th century, the harquebus was invented, which included both a trigger and a stock. It was a significant advancement, but the weapons were still heavy and took a long time to reload. As such, it was ineffective to have massed ranks made up solely of harquebusiers, as they would only be able to get off one shot before being overwhelmed by the enemy.As such, harquebusiers and other ranged-weapon-wielding soldiers were added to the fringes of pikeman formations. The gunmen would open fire and then retreat behind the pikemen. During this era, battles were often decided by the push of the pike rather than by firearms alone.In a bid to stay ahead of evolving tactics, horsemen were equipped with pistols, but these were difficult to reload on horseback. Ranks of horsemen would approach the footmen formations, fire at point-blank range, and then veer off. This tactic was employed in waves.The most effective way to break up these powerful pike formations was through the use of cannons, after which heavy cavalry could be used to scatter the fractured formations. Soon, armies throughout all of the major powers in Europe had similar structures, all emphasizing three branchesinfantry, cavalry, and artillery.Fort Bourtange in the Netherlands. Source: Wikimedia CommonsThe offensive power of gunpowder also meant that defensive technology and tactics had to evolve to keep pace. The most conspicuous developments were in how castles evolved, as many of these grand structures are still standing today in full view of the public. Walls were built thicker, and the rounded bastions of medieval castles evolved into pointed designs, giving rise to star-shaped forts. Angled structures were better able to deflect incoming cannon balls.Matchlock to FlintlockMuskets being fired, photograph by Edd Scorpio, 2008. Source: Wikimedia CommonsThe matchlock appeared in the Ottoman Empire and Europe in the second half of the 15th century. It was a huge improvement over the hand cannons in use in that the latter required somebody with a match to light the gunpowder in the guns breech. Matchlocks were fitted with a pivoting fuse that could be mechanically moved into place to ignite the pans gunpowder. They had a trigger mechanism and were safer because they didnt require the manual application of a lit match.Matchlock guns were used extensively from the 16th to the first half of the 18th century in Europe and until the mid-19th century in the Ottoman Empire and in parts of East Asia.A complex wheel-lock firing mechanism from the 17th century, photograph by Paul Harrison, 2019. Source: Wikimedia CommonsMatchlocks were eventually replaced with flintlocks. While matchlocks used a fuse, flintlocks lit the gunpowder with a spark made by striking flint against steel. Wheel-locks were also employed concurrently with matchlocks, and used a spinning mechanism to generate sparks. They could be used in wet weather conditions but were extremely complex and expensive to manufacture. Flintlocks, in comparison with wheel-locks, were simpler and cheaper to produce.Muskets such as the matchlock, wheel-lock, and flintlock were inaccurate but effective at close range in massed volleys. Adding to the inaccuracy was the large amount of smoke produced by these weapons, and battlefields became places of low visibility. Slow reload times meant that musketeer units were vulnerable to cavalry charges and had to have close support from anti-cavalry units such as pikemen.Musketeer tactics involved a highly coordinated maneuver of rotating ranks to keep up a permanent rate of fire. King Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden (r. 1611-1632) is credited with initiating a powerful tactic in which three ranks could fire at the same time. The front rank kneeled, the second rank crouched, and the third rank stood.The advent of muskets and their prevalence on the battlefield also influenced the armor soldiers wore. The apex of armor design in Europe was a fully enclosed and highly mobile suit of full plate exemplified by the German Gothic and Italian White designs. As impressive (and expensive) as these suits were, they were susceptible to musket fire. Armors were proofed by firing pistols and muskets at them. While good armor passed the test for a time, more powerful guns emerged as the decades passed, and armor simply had to get thicker to be able to absorb the velocity of a musket ball.A French cuirass from Waterloo. Source: Wikimedia Commons/Muse de lArme, ParisAs such, armor became heavier, and so those who could afford it opted for armor that only covered half the body. Breastplates and helmets were common until the late 17th century and eventually were done away with as they became an unnecessary encumbrance that could not effectively protect against gunfire. However, the breastplate (cuirass) continued to see widespread use in heavy cavalry units all the way through to World War I.By this time, the vast majority of soldiers went onto the battlefield unarmored. Mle combat did occur, but it was guns that decided the course of battles. And while some units sported sabers and lances, the need for close-combat options was satiated by adding bayonets attached to guns when needed. In doing so, soldiers turned their guns into spears, representing a full circle of combat technology over the millennia.Bayonets also protected infantry against cavalry charges. When under threat from cavalry, infantry units formed squares with bayonets pointing outwards, creating a bristling wall of pointed metal that horses, no matter how well they were trained, would not run into. Horses, however, were still essential parts of all militaries and were only completely replaced in the 1930s and 40s with the advent of tanks and motorized vehicles.In short, guns were the primary weapon, while blades, for the most part, were relegated to being accessoriesa situation that was the complete opposite of when guns were first introduced to the battlefields of Europe. Gunpowder was a vital component of virtually every soldiers kit.Gunpowder in the Age of MechanizationA German railway gun firing across the English Channel. Source: Wikimedia Commons/National Museum of the US Navy, Washington DCAs the world industrialized, gunpowder weapons became deadlier. Muzzle-loaders gave way to breech-loaders. In the late 19th century, automatic guns featured on the battlefield, and by World War I, artillery was king.Before an attack, artillery barrages lasted for hours, days, and sometimes even weeks, driving soldiers insane and turning the entire battlefield into mud. By this time, traditional gunpowder had been replaced by smokeless powder as a propellant. Although the recipe was different, the name remained the same in colloquial terminology, as did its purpose. Today, smokeless powder and other powdered propellants are often referred to as gunpowder, even though they are not the same.As gun technology became more sophisticated, so too did vehicles. Tanks appeared in World War I and became essential to combat operations in World War II, while in the skies, aircraft deployed bullets and bombs to destroy their enemies.Destruction in Ukraine. Source: Wikimedia Commons/State Emergency Service of Ukraine (Dsns.gov.ua)Today, the battlefield is a dynamic and dangerous place. Modern developments have seen shifts towards the effectiveness of drones and missiles, while the perception of the dominance of tanks has taken a knock. This terrifying and hellish world is one that owes its existence to gunpowder and the foundation it built for the evolution of modern warfare.

0 Σχόλια

0 Μοιράστηκε

115 Views