0 Comments

0 Shares

1K Views

Directory

Elevate your Sngine platform to new levels with plugins from YubNub Digital Media!

-

Please log in to like, share and comment!

-

Apex Legends' ranked mode changes make me feel like a pro playerApex Legends' ranked mode changes make me feel like a pro player As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases and other affiliate schemes. Learn more. As with every new season of every new live-service game, Apex Legends has seen myriad changes in Season 26. There's no new character or weapon, but developer...0 Comments 0 Shares 1K Views

-

WWW.LIVESCIENCE.COMHiker picks up venomous snake, dies after bite triggers rare allergic reaction, authorities sayAuthorities say a man died after being bitten by a venomous snake in Tennessee. The snake is believed to be a timber rattlesnake, which can have extremely potent venom, but the man likely died due to a rare allergic reaction.0 Comments 0 Shares 135 Views

WWW.LIVESCIENCE.COMHiker picks up venomous snake, dies after bite triggers rare allergic reaction, authorities sayAuthorities say a man died after being bitten by a venomous snake in Tennessee. The snake is believed to be a timber rattlesnake, which can have extremely potent venom, but the man likely died due to a rare allergic reaction.0 Comments 0 Shares 135 Views -

WWW.LIVESCIENCE.COMWhere can you see the Sept. 7 'blood moon' total lunar eclipse?The second and final 'blood moon' total lunar eclipse of 2025 is coming on the night of Sept. 7-8. Here's where the celestial spectacle will be visible and how to watch it if you're not in the path.0 Comments 0 Shares 136 Views

WWW.LIVESCIENCE.COMWhere can you see the Sept. 7 'blood moon' total lunar eclipse?The second and final 'blood moon' total lunar eclipse of 2025 is coming on the night of Sept. 7-8. Here's where the celestial spectacle will be visible and how to watch it if you're not in the path.0 Comments 0 Shares 136 Views -

WWW.IFLSCIENCE.COMNew Jersey Officials Investigate Possible First Locally Acquired Malaria Case Since 1991The affected individual has no recent international travel history.0 Comments 0 Shares 135 Views

WWW.IFLSCIENCE.COMNew Jersey Officials Investigate Possible First Locally Acquired Malaria Case Since 1991The affected individual has no recent international travel history.0 Comments 0 Shares 135 Views -

-

WWW.PCGAMESN.COMI played Hollow Knight Silksong, and it might just be worth the 8-year waitLets put the conspiracies to bed once and for all: Hollow Knight: Silksong is real. At least, a 15-minute demo of it is. I just went hands on with Steams most wishlisted game while testing out the new Xbox Ally X at Gamescom, and the long-awaited Metroidvania doesnt disappoint. Does it do anything unexpected or widly different from its beloved predecessor? Not from what I saw. But does it deliver top-tier platforming, engaging exploration, a mysterious world, and tricky boss fights? Oh yes. Continue reading I played Hollow Knight Silksong, and it might just be worth the 8-year waitMORE FROM PCGAMESN: Best Indie Games, Hollow Knight Silksong release date, Upcoming PC Games0 Comments 0 Shares 140 Views

WWW.PCGAMESN.COMI played Hollow Knight Silksong, and it might just be worth the 8-year waitLets put the conspiracies to bed once and for all: Hollow Knight: Silksong is real. At least, a 15-minute demo of it is. I just went hands on with Steams most wishlisted game while testing out the new Xbox Ally X at Gamescom, and the long-awaited Metroidvania doesnt disappoint. Does it do anything unexpected or widly different from its beloved predecessor? Not from what I saw. But does it deliver top-tier platforming, engaging exploration, a mysterious world, and tricky boss fights? Oh yes. Continue reading I played Hollow Knight Silksong, and it might just be worth the 8-year waitMORE FROM PCGAMESN: Best Indie Games, Hollow Knight Silksong release date, Upcoming PC Games0 Comments 0 Shares 140 Views -

WWW.PCGAMESN.COMApex Legends' ranked mode changes make me feel like a pro playerAs with every new season of every new live-service game, Apex Legends has seen myriad changes in Season 26. There's no new character or weapon, but developer Respawn has mixed things up in other ways. The E-District map can be seen in the daytime for the first time, the RE-45 has gone from a useless sidearm, left discarded as soon as you find a decent SMG, to one of the best weapons in the game. But it's Respawn's changes to ranked mode that have made the most impact on my matches and, thankfully, it's patched some of those changes in response to player feedback. Continue reading Apex Legends' ranked mode changes make me feel like a pro playerMORE FROM PCGAMESN: Apex Legends characters guide, Apex Legends skins, Apex Legends tier list0 Comments 0 Shares 140 Views

WWW.PCGAMESN.COMApex Legends' ranked mode changes make me feel like a pro playerAs with every new season of every new live-service game, Apex Legends has seen myriad changes in Season 26. There's no new character or weapon, but developer Respawn has mixed things up in other ways. The E-District map can be seen in the daytime for the first time, the RE-45 has gone from a useless sidearm, left discarded as soon as you find a decent SMG, to one of the best weapons in the game. But it's Respawn's changes to ranked mode that have made the most impact on my matches and, thankfully, it's patched some of those changes in response to player feedback. Continue reading Apex Legends' ranked mode changes make me feel like a pro playerMORE FROM PCGAMESN: Apex Legends characters guide, Apex Legends skins, Apex Legends tier list0 Comments 0 Shares 140 Views -

WWW.THEKITCHN.COMReeses Just Launched a Limited-Edition Peanut Butter Cup for Fall Thats So Good, Im Eating Them by the HandfulEat them by the handful.READ MORE...0 Comments 0 Shares 139 Views

-

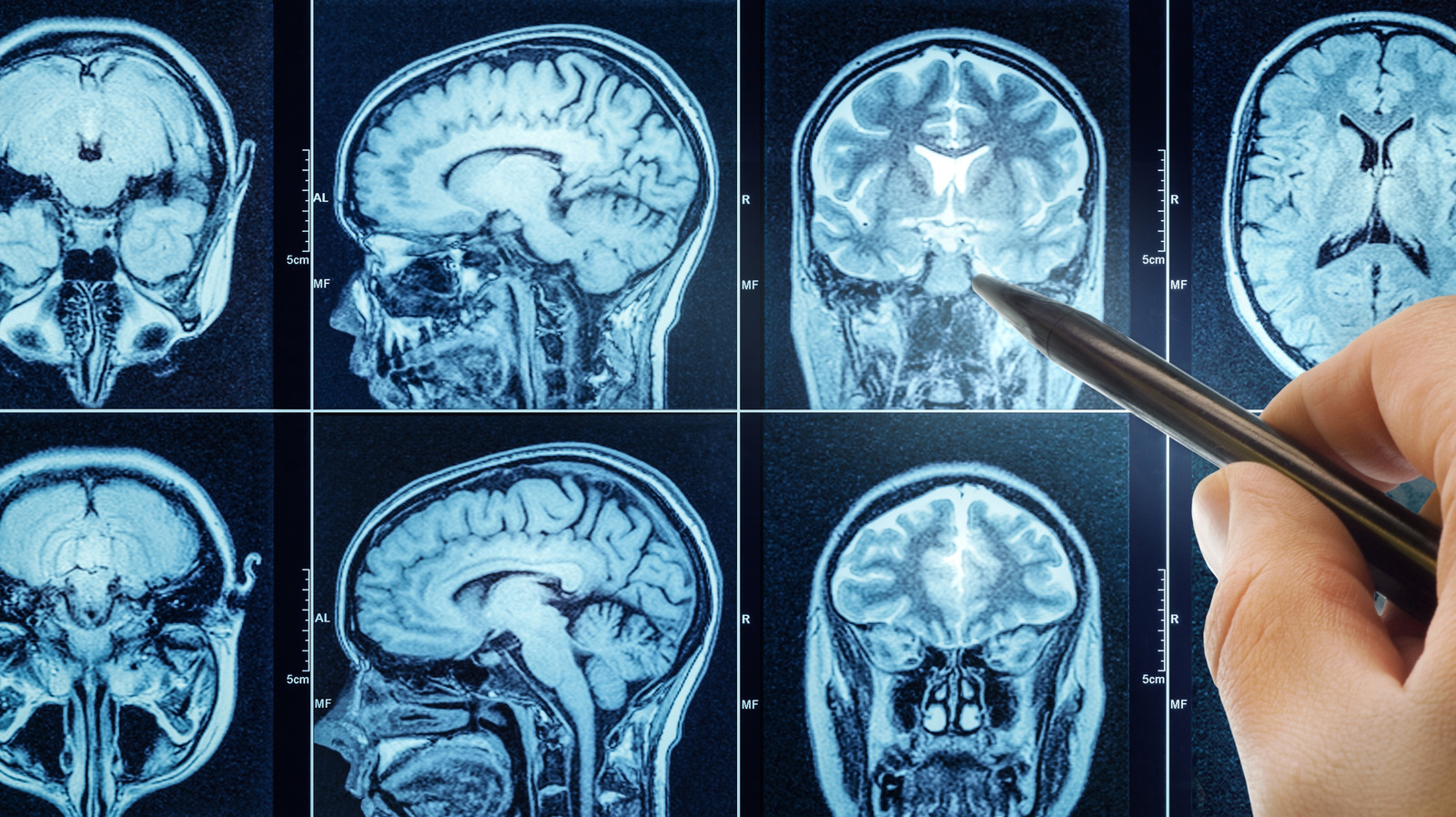

WWW.BGR.COMNew Study Suggests Certain Memories May Drift In The BrainA new study reveals that the memories of mice may not stay located in just one spot in the brain, something that may also prove true with humans.0 Comments 0 Shares 139 Views

WWW.BGR.COMNew Study Suggests Certain Memories May Drift In The BrainA new study reveals that the memories of mice may not stay located in just one spot in the brain, something that may also prove true with humans.0 Comments 0 Shares 139 Views