-

Feed de Notícias

- EXPLORAR

-

Páginas

-

Blogs

-

Fóruns

How Hero Of Alexandria Used Ancient Science To Make “Magical Acts Of The Gods” 2,000 Years Ago

How Hero Of Alexandria Used Ancient Science To Make “Magical Acts Of The Gods” 2,000 Years Ago

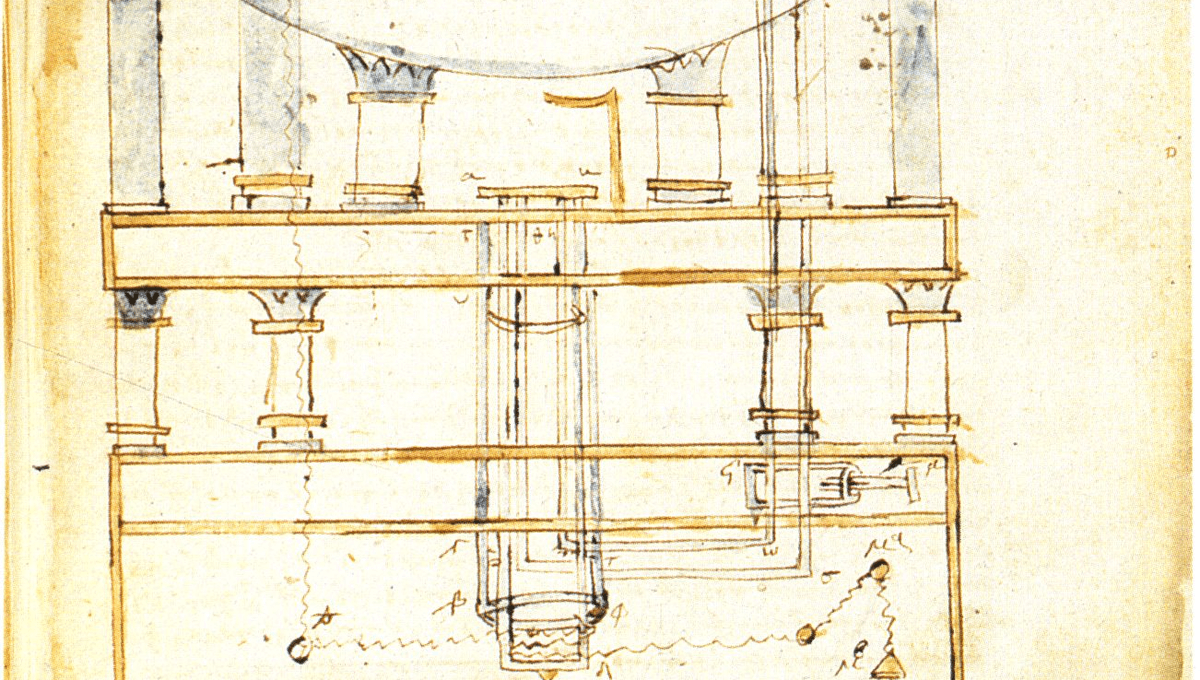

Almost 2,000 years ago, a mathematician and engineer created machines that so impressed the public that his instructions have survived to this day. The details of Hero of Alexandria’s life are sufficiently vague that there is debate about his name, and the century he lived in, so accounts of his works need to be taken with a grain of salt. Nevertheless, there seems little reason to doubt that he used an understanding of what we now call physics to create many works considered astonishing at the time, and that still look remarkably advanced today.

The rest of this article is behind a paywall. Please sign in or subscribe to access the full content. Hero, also known as Heron, is reputed to have developed elements of two technologies that went on to change the world: the steam engine, known as Hero’s engine, and the windmill. Although neither of these was entirely his innovation, Hero advanced them enough to gain credit across the Roman Empire and long thereafter. Whether the Empire teetered on the edge of an industrial revolution is still debated. Meanwhile, Hero also used his machines as theatre props and fooled the audience’s eyes. He might be considered the first recorded figure to demonstrate the truth of Arthur C. Clarke’s famous saying: “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” Hero developed machines we might now call special effects, for theatre performances, for example, dropping metal balls onto a drum using a timed mechanism to imitate the sound of thunder. Although his thunder machine may have been suited to use more often, from our perspective, two plays entirely composed of puppets operated by a cylindrical wheel turned by a weight falling at a preset rate represent more impressive contraptions. One showed the god Dionysus pouring wine on an altar while figures danced around him and musical instruments were played, all without the intervention of a human once set in motion. The other showed ships being built and launched into a sea from which dolphins leapt, before being led astray to founder on rocks and their sailors be struck down by Athena’s lightning. A modern audience shown such a display might try to reverse engineer it in their heads, working out what Hero had done. To contemporaries who had not read the manual, it may have seemed the gods themselves were powering the displays. The Catoptrica, possibly written by Hero, prefigured Newton’s Opticks, describing the way flat and curved mirrors affect light, and can be used to create illusions. Hero also described toys for children, including examples of: “Trick jars that give out wine or water separately or in constant proportions, singing birds and sounding trumpets, puppets that move when a fire is lit on an altar, animals that drink when they are offered water.” The last of these may have resembled the drinking bird toy that is still sold as a desk ornament today and depending on an understanding of the concept of center of mass and angular momentum. Proving just how far ahead of his time he was, Hero even described, and probably created, the first vending machine, where a coin was rewarded with a suitable amount of water. Presumably, something more valuable like oil, wine, or grain could have been returned instead. The machine used the weight of the coin to operate a lever upon falling into a pan, so perhaps could have been fooled by a suitably heavy stone, but the idea was there. To achieve many of these feats, Hero needed to understand key aspects of physics, such as the behavior of fluids, both liquids and gases. He wrote books on mathematics and mechanics that provide formulae for the areas of triangles and the volume of shapes, but how much of this was original will probably never be known. However, to most of his audience, these must indeed have seemed like the work of a magician or one who had gained the favor of the gods. Much of Hero’s work drew on that of Archimedes, who, while not quite the innovator portrayed in the latest Indiana Jones movie, still combined a principle still taught in science classes today with technology that would have seemed miraculous. These included the capacity to drive water uphill and hurl items over immense distances. However, where Archimedes used his machines to feed people or win battles, Hero appears to have devoted much of his work to creating wonder and entertainment, like modern magic shows. It’s possible that Hero devoted so much time to these items because wowing the public was his livelihood or joy, but science historian AG Drachmann argues, “Hero was a teacher of physics, of which pneumatics is part. The book is a text for students, and Hero describes instruments the student needs to know, just as a modern physics textbook explains the laws governing the spinning top or the climbing monkey. Playthings take up so much of the book because such toys were very much in vogue at the time and the science of pneumatics was used for very little else.” Before the printing press, copying books was such arduous work that few were made. When the famous library of Hero’s city burned, it may have taken with it the only records of even more ancient magicians, who had similarly harnessed physics to create illusions. If so, it would take more than a thousand years for Galileo, Newton, Boyle, and co to rediscover their science, allowing others to put the principles to more serious applications that now power the world. Love magic? Director of the UK’s only MAGIC Lab, Dr Gustav Kuhn, will be at our CURIOUS Live Christmas Special on December 11. Join us for the watch party if you'd like to ask Dr Kuhn questions about The Science Of Magic.