WWW.THECOLLECTOR.COM

Colonialism in Tasmania, Australia (What You Should Know)

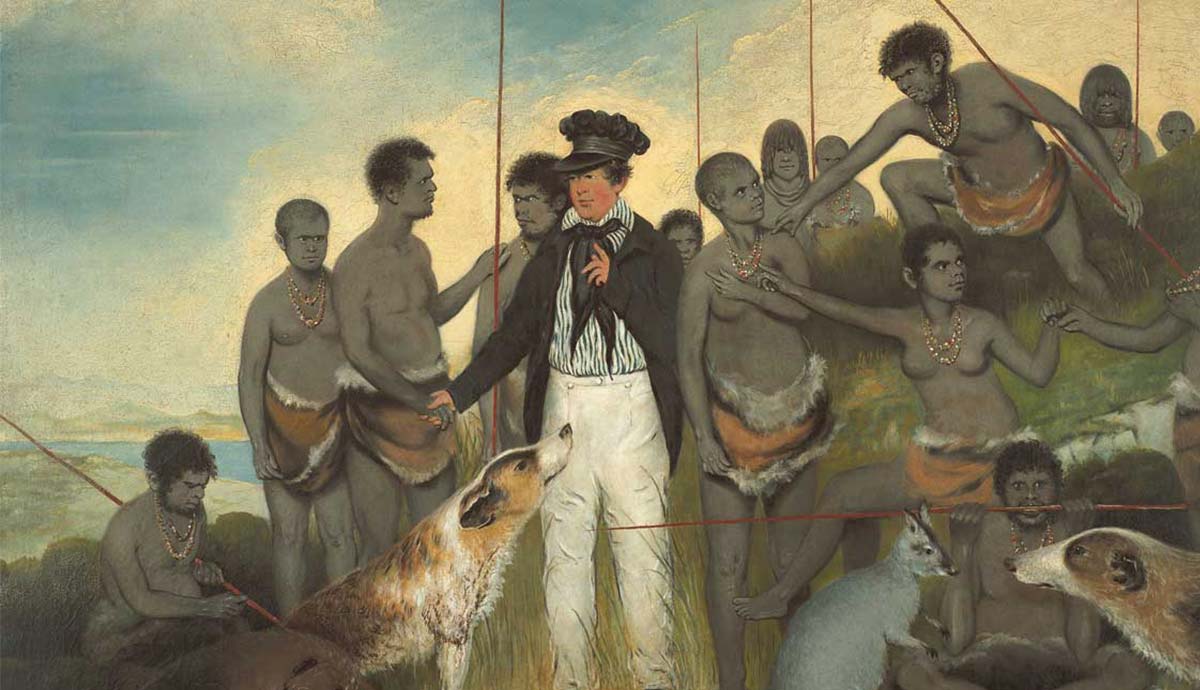

British colonialists arrived in Tasmania, Australia (at the time known as Van Diemens Land) in 1803. Today historians have demonstrated that in 1803, the Aboriginal population counted between 6,000 and 8,000 people and up to 100 clans. The exact number is impossible to determine, but Brian Plomley (1912-1994) has identified 48 of them. From the arrival of the first settlers to the first massacres, and from the massive pastoral invasion of the late 1910s to the establishment of Aboriginal missions at Flinders Island and Oyster Cove, Tasmania truly is, to put it with historian Lyndall Ryan in her Tasmanian Aborigines, the best place to understand the dreadful impact of settler colonialism on Aborigines across Australia.Tasmania, Before 1803Bay of Fires in Tasmania, home to the North East nation, photograph by Spencer Chow, 2020. Source: UnsplashBefore the arrival of Europeans in 1803, Aboriginal people had inhabited, survived, and thrived on Tasmanian land for at least 40,000 years. Back then, the island was still connected to mainland Australia by a land bridge which was eventually submerged with the rise of sea levels. It was only around 6,000 years ago that Aboriginal clans began occupying the islands east coast and the interior, settling along the many rivers around the islands thousands of lakes the north-east section of the Central Plateau alone has about 4,000, Ryan writes in Tasmanian Aborigines.Women were tasked with collecting berries and vegetable roots (which they did by using wooden digging sticks), as well as hunting wombats, possums, and other small animals like rats, penguins, and bandicoots. Women from coastal clans would dive to great depths to collect crayfish, mussels, and abalone, while their male counterparts used wooden spears to spear scale fish and stingrays, and hunt seals, emus, kangaroos, and wallabies.They hunted kangaroos relying on firestick farming techniques, which also allowed them to manage the plains. Almost every part of the animal was used.Blacklip Abalone, women from coastal clans would dive to great depths to collect abalone. Source: Australian MuseumOchre was their sacred color, used in ceremonies and as a gift. It was mined predominantly at Mount Housetop, Mount Vandyke, St Valentines Peak, and Gog Range, on lands belonging to the North Nation. Corpses were usually decorated with ochre (and clay) before being wrapped in leaves, feathers, and/or animal skins, depending on the persons clan.Upon contact, Aboriginal Tasmanian society was organized into nine separate nations which today are known exclusively by the names British colonialists assigned them. Each nation was formed by several clans with similar cultural practices. They would speak the same language (or dialect), live in contiguous regions, and share similar seasonal movements. The clan was the basic social unit at the heart of Aboriginal society.After 1803 and Before the Pastoral InvasionConvicts writing letters home at Cockatoo Island in New South Wales, drawing by Philip Doyne Vigors, 19th century. Source: National Museum of AustraliaThe first years of colonization, from 1803 to 1807, were marked by a mixture of relatively friendly encounters and brutal clashes. Interactions between settlers, Aboriginal clans, and escaped convicts (also known as bushrangers) were inevitably underscored by misunderstandings and uncertainty. To put it with Ryan, the Aborigines appropriation of dogs, the colonists appropriation of Aboriginal children and the bushrangers appropriation of Aboriginal women led to fraught relations between all three groups.The first large-scale massacre took place on May 3, 1804, at Risdon Cove. Historians consider it the founding massacre in the history of colonial Tasmania. Justifying his murderous actions with lies, Lieutenant William Moore ordered his men to fire on a group of people from the Leenowwenne and Pangerninghe clans from the Big River Nation. They were unarmed, carrying only waddies, and on their autumn migration to the coast.The Lady Nelson, commanded by Lieutenant Bowen to settle the Derwent River. Source: National Museum of Australia1807 was the year everything changed. Violence escalated, rapidly and brutally. Within 20 years, Aboriginal Tasmanians were almost wiped out. In November 1807, more than 100 settler families (that is, more than 600 people overall) arrived in Hobart. Over the course of a few years, they set up numerous farms along the shores of the Derwent, Coal, and Browns River, at Patersons Plains, and New Norfolk. These areas were part of the ancestral lands of the Mouheneenner clan of the South East nation. In just seven years, they had taken control of ten percent of the island and dominated the sealing and whaling industries. By 1820, their occupation had expanded to cover 15 percent of Tasmania.Although some interactions remained friendly, with chiefs exchanging kangaroo skins for colonial products such as tea, flour, tobacco, and dogs, in several instances sealers kidnapped Aboriginal women, especially from the North West and East nations.A large Tasmanian canoe on the eastern shore of Schouten Island, engraving by Charles-Alexandre Lesueur. Source: National Museum of AustraliaIn 1815, sailors and sealers established permanent settlements on various islands in the Bass Strait, on Preservation Island, Gun Carriage Island, and Clarke Island. Here, they lived, married, and had children with Aboriginal women, who took the name of tyereelore, island wives. It only took these women a couple of years to become the backbone of their community.Ryan writes that they fed the community by training the dogs to track down wallabies, while they climbed trees to catch possums and dived for kelp and shellfish. To keep the settlements economically viable, they dried and cured seal and kangaroo skins and made baskets and necklaces for sale in Launceston; and to keep their own traditions alive, they sang, told stories of their people and performed ceremonial dances.Tasmanian necklace created by Aunty Dulcie Greeno and made of collected shells. Source: National Museum of AustraliaThe so-called Straitsmen and their Aboriginal wives, and children are the most vivid example of a different kind of cross-cultural, peaceful interaction, a unique case where different cultures met and thrived. They spoke Aboriginal English and often wore a mixture of Western and Aboriginal clothes.Meanwhile, in the Van Diemens colony, massacres continued, along with child abduction. Most of them were raised to live a life of servitude. In 1818, the Hobart Town Gazette began to address the colonial treatment of Aboriginal people and inquired who was to be considered responsible for their suffering. Just a few years later, the Black War began.A Different Kind of InvasionCradle Mountain in the Central Highlands region is home to the Big River and North nations, photograph by Laura Smetsers, 2018. Source: UnsplashThe first wave of free settlers landed in Van Diemens Land in the early 1820s. The group consisted of members of the British (English, Scottish, and Irish) landed gentry, retired army and naval officers, and groups of sons of colonial officials previously stationed across the British Empire. Most of them were accompanied by their families.The numbers provided by Lyndall Ryan are astounding. In 1823 alone, more than 1,000 land grants totalling 175,704 hectares were made to the new settlers, the largest alienation of land in a single year in the entire history of Tasmania. By 1830 nearly half a million hectares had been granted. Between 1816 and 1823 the sheep population increased from 54,600 to 200,000 and by 1830 it had reached one million, surpassing for a short time the number of sheep in New South Wales. With sheep came fences. With fences came huts and stone walls. With huts came homesteads.General chart of Terra Australis or Australia, by Matthew Flinders, 19th century. Source: National Museum of AustraliaVan Diemens Land was in the process of becoming a colony centered on the pastoral economy. Settlers were now permanently occupying the lands of the Big River, North, North Midlands, and Ben Lomond nations which became known as the Settled Districts. In May 1824 Lieutenant-Colonel Sir George Arthur (1784-1854) was appointed governor of the colony. An unusual man, he was to hold the position until 1836.Born in Plymouth, England, he had served with the 35th Regiment in Egypt, Sicily, and Calabria, before becoming assistant quartermaster general in Jamaica in 1812. For eight years, starting in 1814, he was Lieutenant Governor of British Honduras. An honest opponent of slavery, he believed that Aboriginal people could be saved, and that they could improve their current situation because they had the skills to do so. All they needed to do was to embrace Christianity (thanks to the help of the Europeans, of course) and surrender their lands.Tasmanian tigers in captivity, the extinction of Tasmanian tigers (or thylacine) was a direct consequence of British colonization. Source: Museums of VictoriaSir George Arthur was confident that his double goal of civilizing Aboriginal people and establishing a flourishing colony could in fact become a reality. Only two years later, on November 29, 1826, to facilitate their surrender in the Settled Districts region, he issued a government notice that effectively set the stage for the Black War. Pastoralists, settlers, and convicts could legally kill Aboriginal people when found attacking their property or cattle. They did. The law was on their side.The Black War and the Black LineAboriginal people in Van Diemens Land, painting by John Glover, 1840. Source: LouvreIn 1826, more than 3,000 settlers and convicts arrived on Van Diemens Land. It was the largest number since 1803. Most of them settled in the Campbell Town District, on the traditional hunting grounds of the Tyerrernotepanner clans of the North Midlands Nation. Prevented from hunting or gathering food on their ancestral territories, Aboriginal groups grew hungry. They were reported entering and raiding huts looking for bags of wheat, salt, bread, flour, and blankets.Following two years of massacres and killings, on April 19, 1828, George Arthur issued another proclamation. It divided Van Diemens Land into two sections, one specifically for the Europeans and the other for Aboriginal tribes so that they could be civilized. He also intended to engage in negotiations with Aboriginal leaders, mainly with the Kickerterpoller and probably the Umarrah from the North Midlands Nation. He was also open to the possibility of a treaty and seasonal passage through the Settled Districts.Port Arthur, established in 1830 as a timber station and then a convict settlement. Source: National Museum of AustraliaBut once again violence soon escalated. Between August and October, the Oyster Bay, Big River, Ben Lomond, and North clans launched a series of attacks, one every two days, which killed at least 15 colonists. In October, for the first time, Oyster Bay people killed two women and two of their children at Lake Tiberias, probably in response to the killing of some Aboriginal women.On November 1, 1828, George Arthur declared martial law against the (probably five) Aboriginal clans still operating in the Settled Districts. Aboriginal people were now officially enemies of the Commonwealth and could be shot on sight. Martial law remained in force for more than three years. A new phase of the Black War had just begun.Arthur established small detachments of soldiers to protect the most remote settlements as well as military patrols, who had orders to scour the area and kill or capture any Aboriginal man, woman, or child they found.Convict settlement near Gosford, New South Wales. Source: National Museum of AustraliaIn May 1829, a small troop of mounted police began assisting military patrols, now operating alongside private settler parties. Violence continued to escalate, with Aboriginal people spearing settlers (including women and children), burning down their huts, stealing flour and bread, and settlers responding by butchering Aboriginal groups at night in their camps (including women and children).This outbreak of violence culminated in the so-called Black Line. In September 1830, Arthur devised a plan to drive Aboriginal people out of the Settled District. He called on every able-bodied man, free or convict, to form a human chain along with the military and police forces. Until the end of November, when the operation was called off, 2,200 settlers methodically scouted the island, advancing in a pincer movement, with the intent of driving the remaining Aboriginal men, women, and children into the Tasman peninsula, the designated place for an Aboriginal mission.From Gun Carriage Island to Flinders IslandAboriginal people on Flinders Island, painting by John Skinner Prout, 19th century. Source: National Museum of AustraliaThe Black War ended with the surrender of Aboriginal nations across the island. It didnt happen overnight. Instead, it was a gradual process facilitated by the joint efforts of George Arthur and George Augustus Robinson (1791-1866), his conciliator among Aboriginal people. Ryan describes Arthur as the first colonial governor to grapple with what became the great moral dilemma of settler colonies in the Anglophone world, that is, should the British government permit the extermination of Indigenous peoples like the Tasmanian Aborigines by white settlers or should they be removed to a safe haven and civilized into British ways?Robinson believed they could and should be civilized. Starting in 1829, he undertook extensive trips across the island, first among the South West, North, and North West nations, and later in the Settled Districts, to meet and try to convince Aboriginal people to relocate to specific areas allotted to them.Between 1830 and 1834, Truganini, pictured here in 1869, accompanied Robinson on his missions across Van Diemens Land, photograph by Alfred Winter, 1869. Source: Wikimedia CommonsThe first of these safe havens was Gun Carriage Island, a relatively small island between Cape Barren and Flinders Island, 57 kilometers (35 miles) off the coast of Van Diemens Land. In just a few weeks, the clans despatched there wasted away, succumbing to illnesses and lack of fresh food. The Gun Carriage Island plan was abandoned.By January 1832, all Aboriginal clans in the Settled Districts had surrendered. The largest group (26 people from the Big River and Oyster Bay nations), led by Montpeliater and Tongerlongter, surrendered (peacefully) to Robinson on December 31, 1832. They were all taken to Flinders Island. Soon after, as it had on Gun Carriage Island, people started to become ill. Some of their leaders, including Umarrah, his wife Woolaytopinnyer, and Kickerterpoller, perished. Outside the Settled Districts, the North West and South West nations proved more difficult to convince.Robinson and his men (including a group of Aboriginal people) had to use force to bring them in. Some were sent to Grummet Island, where many perished. Eventually, a group of remaining Ninene from the South West nation surrendered and was taken to Flinders Island, where the so-called Wybalenna Aboriginal Establishment had been set up in 1833 (it ceased operations only in 1847).In 1835, Robinson became the superintendent of Wybalenna. The Establishment was formed by 112 Aboriginal men and women belonging to three distinct groups and led by seven chiefs. The largest group comprised 46 people from the South West and North nations (including Truganini from the South East nation). Another group was made up of people from Ben Lomond, North Midlands, and North East nations, while the smallest group comprised members of the Big River and Oyster Bay nations. Wybalenna served as the basis for assimilation programs across Australia.Petition to the QueenPoliceman on a horse on Flinders Island, 1920s. Source: Furneaux MuseumMany important Aboriginal figures passed through the ordeal of Wybalenna and many died here of influenza and poor living conditions. William Lanney, for instance, arrived at Wybalenna with his family, one of the last to surrender, in 1842. To put it with Ryan, They finally gave themselves up in 1842 near the Arthur River because, they said, they were lonely. Five years later, Lanneys parents and two of his brothers were dead.Wybalenna, however, also saw the emergence of important Aboriginal leaders and the beginning of Aboriginal activism on Tasmanian soil. Walter Arthur (1820-1861), his wife Mary Ann, and Davy Bruny, for instance, could speak and read English. They were aware of their legal rights and demanded payment for their work at the Establishment. Flinders Island, they maintained, belonged to them and it was the white man who was supposed to meet their demands, not the other way around.The Conciliation, painting Benjamin Duterrau, 1840. Source: National Portrait GalleryIn December 1845, Walter Arthur, then aged 27, wrote to George Washington, an influential Quaker in Hobart, that his people on Flinders Island could manage themselves. They did not need commandants or superintendents. A few months later, on February 17, 1846, he and seven others petitioned Queen Victoria herself. Maintaining that they were free and that they had freely given up their country, they asked her not to have Jeanneret appointed again as superintendent, given his brutal methods.The petition led to an inquiry. Lieutenant-Governor Denison decided to transfer the Aboriginal men and women from Flinders Island to their final home, an abandoned penal station at Oyster Cove, 30 kilometers (18 miles) south-east of Hobart on the western side of the DEntrecasteaux Channel. They arrived there on October 18, 1847. They didnt (and couldnt) know that the penal station had been abandoned in 1835 because it had failed to meet convict health standards.Tasmanian bark canoe, photograph by Rex Greeno. Source: National Museum of AustraliaAt Oyster Cave the death rate was astonishing. Deprived of their children (who had been taken to an Orphan School in Hobart), and living in cold and damp houses, some of the men and women stationed there succumbed to depression and alcohol. Others managed to adjust, working for settlers, hunting and collecting shellfish in the DEntrecasteaux Channel. However, Ryan notes that each time one of them died, they would leave the station for a period of time before, inevitably, coming back.In July 1871, after Mary Anns death, Truganini was the only woman still at Oyster Cove. She died in 1876. She was not, however, the last Aboriginal Tasmanian, as colonial propaganda has portrayed her for decades. Today the descendants of Fanny Cochrane Smith (1834-1905), Dolly Dalrymple Johnson (1808-1864) in northern Tasmania, and the Islanders community in the Bass Strait are ensuring the survival of Aboriginal culture in contemporary Australia.

0 Commentarii

0 Distribuiri

209 Views