WWW.THECOLLECTOR.COM

Why Do We Keep Finding Mayan Pyramids?

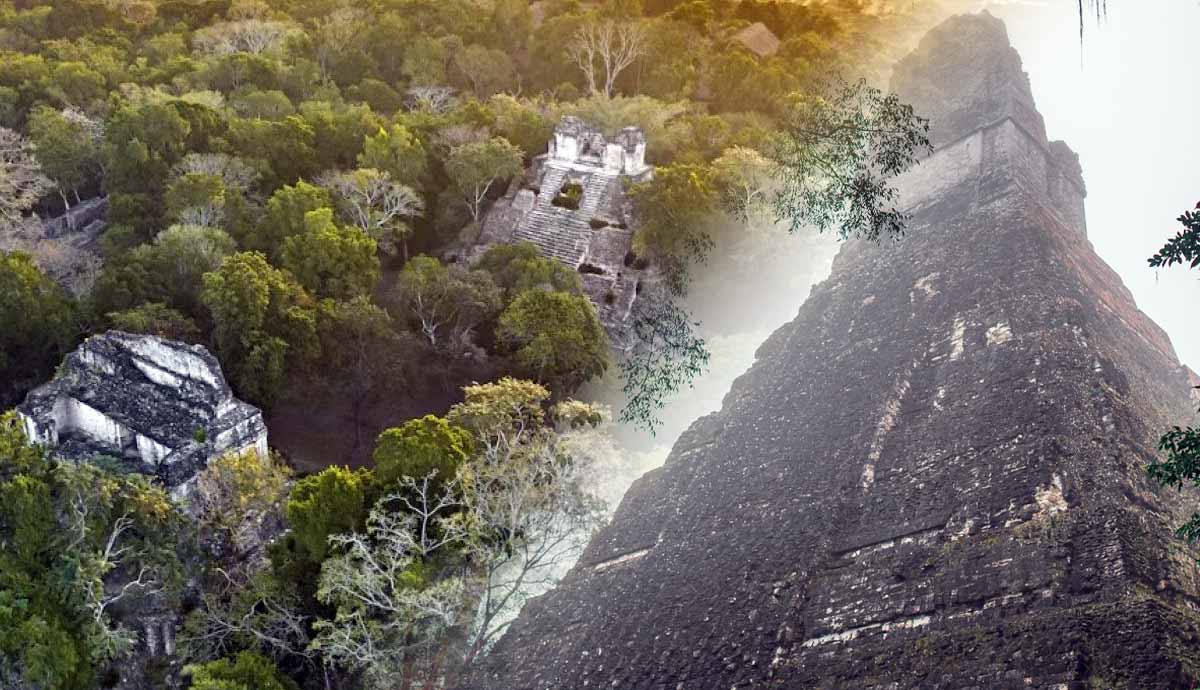

Traditionally, excavations deep in the jungles of Mexico, Central, and South America are difficult at best and dangerous at worst. With rough terrain, violent storms, and the watchful eyes of local animals, archeologists often turn to modern equipment to cover as much ground as possible without disrupting the local wildlife. As more land is excavated, previously insignificant hills are revealed to be dirt mounds that gradually formed over the ruins of Mesoamerican cities.Layout: What Maya Cities Looked LikeTikal (c. 400 BCE900 CE). Source: Visit Centro AmericaIn order to find lost cities, one must first know what a Maya city looked like and where to start the search. The majority of pre-Columbian or Mesoamerican (prior to Spanish arrival in the 16th century) Maya civilizations were grouped together in the modern-day countries of Honduras, El Salvador, Guatemala, Belize, and southern parts of Mexico, where their living Maya descendants still reside today.Many of what are known as Maya pyramids were part of larger ceremonial and cultural centers like Chichn Itz, Tikal, and Palenque, similar to present-day capital cities. And just like modern suburbs, smaller villages and towns would have surrounded each of these bustling cities. With more land available, many villages produced crops like maize to import into the larger cities and neighboring towns.Maya Site of Copan, Honduras (Early Classic Period, c. 250-550 CE), photo by Ko Hon Chiu Vincent. Source: UNESCOThe Maya were very elaborate and intentional builders. A city layout might resemble a specific glyph to commemorate the final date of completion, especially when viewed from above by their gods. Typically, these large cities were built around a center structure, usually a ceremonial site or dedicated administrative center.This private walled-off section would have not only contained any temples or ceremonial pyramids, but also a dedicated residential area for religious leaders and elite members of society. Unlike the smaller villages and residential areas, this section of elite housing and ceremonial center was built for the gods, and built to last. Tall and regal, these temples and elite apartments often towered over the surrounding area, closer to the sky and closer to the gods.Mayan Pyramids: Temples and TombsTikal National Park, Guatemala (c. 200-900 CE), photo by Silvan Rehfeld. Source: UNESCOThe Maya were incredible builders, impressive even by todays standards. One of the most impressive pieces of a Maya city, and ultimately the easiest to find in a jungle, is the citys main temple or pyramid. With something as large as a pyramid, it might be surprising to know many of these once-thriving civilizations have long since been covered by layers of earth. Many of these cities faced erosion or outside forces that slowly tore down the buildings brick by brick. The jungles in which the Maya built their cities are notoriously difficult to inhabit and tend to grow over any evidence of humanity left behind.Pyramids in Mesoamerica differ quite a bit from the ones on the other side of the world in Egypt. While Egyptian pyramids were built to have a smooth finish on all sides and point in a straight line towards the peak, Mesoamerican pyramids were built like massive steps with a platform near the top. In addition, Egyptian pyramids mainly functioned as tombs or vessels into the afterlife, while Maya pyramids and temples mainly served religious purposes, though they remained closely tied to the dead.El Castillo, Chichen Itza, Mexico (c. 8001200 CE). Source: Mayan PeninsulaThese pyramids functioned as an important meeting place for religious and political announcements, especially during pivotal times of the year: a solstice or equinox. The Maya were intimate time keepers and often used pyramids and architecture to reflect important solar events. For example, the pyramid El Castillo at Chichen Itza likely gathered massive crowds in the spring and fall when the sun casts a snake-like shadow that slithers down the steps during the biannual equinox. These events were deeply connected to the cycles of life, death, and human sacrifice, as Maya pyramids often represented the entrance to Xibalba, the Maya underworld.Much like the ancient Egyptians, archeologists have found elite members of society, like the wealthy or ruling class, entombed in the bases of pyramids across Maya lands. Often these temples were constructed around the burial in honor of the deceased and their connection to the deities represented in the temple. However, not all Maya pyramids were built as tombs; many of them were religious or political structures first that were later altered to accommodate a burial.The Scale of an EmpireAerial view of Dzibanche, Mexico (Classic Period, c. 250 CE900 CE), photo by Silvan Rehfeld. Source: National GeographicOver an estimated span of 3,000 years, the Maya Empire had plenty of time to grow and expand across the jungles of Mexico and Central America, engulfing the Yucatan Peninsula. Archeologists have found evidence of cities as far north as Dzibilchaltun and as far south as Copan. While not all cities on the known Maya map were built or occupied at the same time, it does show the expanse of the empire.As new discoveries are made and new research emerges, the timeline of the Maya Empire also changes. It is impossible to pinpoint the exact moment an empire is born or falls, but experts can estimate the time frame in which a site was inhabited. Luckily, there are scientific methods to help archeologists make those educated guesses.Archeologists use radiocarbon dating, often abbreviated to C14 dating, to approximate the age of organic materials, including plant, animal, and human remains. These organic materials contain carbon which very slowly decomposes over thousands of years. Scientists measure the decay of a specific carbon isotope called carbon-14 to determine a highly accurate age for an organic artifact. This means, as more Maya sites are discovered, scientists can use C14 dating to gain a better understanding of the Maya timeline and scale.Evidence suggests that the Maya Empire was nothing short of massive, with complex societies and interconnected roads, rivaling the size and advancement of similar empires around the same time, such as the Romans. Unfortunately, this also means there is a lot of ground to cover when searching for new sites. So, how do researchers know where to look?Civilization Hiding in Plain SightMap of an ancient Mayan city in present-day Guatemala, revealed using LiDAR technology. Source: National GeographicWith modern-day technology like LiDAR (short for light detection and ranging) and drones for overhead photography, it is significantly easier to get a different view above or below the treeline. LiDAR can help determine the density of an earth mound by sending powerful light waves through the ground and calculating the time and depth it took for the light waves to return to the source. This method is key to finding temples and cities long since reclaimed by the jungle.Archeologists have used LiDAR to discover entire cities lost to the jungle, like Ocomtn in the Yucatan Peninsula. In 2023, renowned archeologist Dr. Ivan prajc and his team used LiDAR to find evidence of a completely unknown Maya city in Mexico. The ruins and scattered artifacts were dated towards the end of the Classic Period, c. 600-900 CE. Likewise, LiDAR has been used across water sources, leading to the discovery of many artifacts under lakes or off the coast of Latin America. In 1998, an entire set of untouched Maya ruins was found under Lake Atitln in Guatemala, now known as the Maya site of Samabaj.Even as recently as 2024, archeologists uncovered theory-shattering secrets about the Maya city of Dzibanche in Mexico, thanks to the use of LiDAR. The latest discovery at Dzibanche includes an impressive map of interconnected and paved highways linking remote Maya ruins to each other. Now, archeologists believe these cities were on average four times larger than previously estimated, suggesting the Maya empire was much more complex than historians first suspected.Looking Toward the Future: Excavation and PreservationPhoto of the Maya site of Xunantunich, Belize, 2017. Photo by Jaime Awe, PhD. Source: The GuardianExcavations get complicated in modern-day Mesoamerica, where many Maya descendants still live in the Yucatan Peninsula, primarily in Guatemala. Unfortunately, many traditions and much of the oral history have disappeared over time. This is due to the fall of the Maya, the details of which are still debated throughout archeology, the rise of the Aztecs, and the eventual forced introduction of Christianity by the Spanish.In recent years, local governments have teamed up with archeological programs working throughout Mexico and Central America to help preserve what remains of the Maya identity in these regions. Programs such as the Belize Valley Archeological Reconnaissance Project (BVAR), South Tikal Archaeological Project, and PACUNAM work closely with universities and researchers across the world as well as the local government. Many of these programs advocate for the historical preservation and integrity of cultural sites amid ongoing excavations.More eyes on these parts of modern Mesoamerica often mean more money and research is funneled into the protection of Maya cultural heritage. This also promotes regulations governing who is allowed to remove things from these sites, to prevent loss or theft of history, though this is difficult to enforce in something as dense and widespread as a jungle. Hopefully, in the next few years, more conservation efforts can further excavate uncharted parts of the jungle and uncover long-lost secrets of the Maya. With all the amazing technology and methods now introduced to archeology, there is no telling what the future will uncover.

0 Commenti

0 condivisioni

18 Views