WWW.THECOLLECTOR.COM

Richard the Lionhearts Final Siege at Chlus Castle

Following his legendary exploits in the Holy Land during the Third Crusade, Richard the Lionheart spent more than a year in German captivity. After his release in 1194, he embarked on a war against King Philip II of France to reclaim territories that had been lost during his captivity. Although Richard had methodically retaken much of the lost territory, his death following the Chlus Castle enabled Philip to take most of Englands French possessions.Richard the Lionhearts Return From the LevantMap of the 3rd Crusade, Source: TheCollectorIn the 12th century, King Richard I of England was one of the most formidable warriors in the Christian world. Richard the Lionheart, as he is known in popular memory, led an army of Christians from all around Europe to the Levant in order to retake Jerusalem from Saladins Sultanate. Joining him were King Philip II of France and King Frederick I Barbarossa of the Holy Roman Empire. It became known as the Kings Crusade and almost succeeded in its goals.Richard gained credibility as a formidable battlefield leader when his army defeated the Muslims at the Siege of Acre and the Battle of Arsuf. Despite his battlefield prowess, he was unable to take Jerusalem as he lacked the forces and siege equipment necessary for such an undertaking. He was forced to make a deal with Saladin that allowed Christian pilgrims to enter the city but ensured that Jerusalem and its hinterland would remain in Muslim hands. This disappointed many people in Western Europe who hoped for the return of Jerusalem to Christian rule.On his way back to England in 1192, Richard was taken captive by Leopold of Austria after the latter accused Richard of arranging the death of Leopolds cousin, Conrad of Montferrat. Leopold sold Richard to Holy Roman Emperor Henry VI, who kept him in prison until February 1194 after receiving a large ransom payment from England. During Richards captivity, his brother John conspired with Philip II to rebel against him and sought to take over his territory in France and England.Political Context of Richard and Philips WarKing Philip II of France receiving an envoy, 1340s. Source: Medievalists.netPhilip II, also known as Philip Augustus, was envious of Richards control over large parts of France. This included parts of Brittany, Aquitaine, and Normandy. When John revolted, Philip agreed to help him in the hope that this would enable France to take control of much of French territory. However, Richards release led to his return to London and being crowned again. John, fearing the wrath of his brother, agreed to reconcile with Richard and refused to fight him.Philips army moved into Normandy and took control of several castles under English control. This threatened Richards position as the Duke of Normandy. He brought an army of English knights, archers, and light infantry with him to retake the castles lost to Philips army. Additionally, he ordered the construction of Chteau Gaillard, one of the most expensive castles constructed in the entire medieval period. Over time, he gathered support from prominent nobles in France and Flanders, enabling him to gain several victories, such as the Battle of Gisors, over Philips forces.In 1199, Richard faced a revolt in the region of Limousin from Viscount Aimar V of Limoges. To crush this revolt, he used brutal force akin to what his Crusaders did in the Levant. Much of this part of central France was completely razed. One of the castles Richard aimed to conquer was Chlus-Chabrol. The reasons for this varied, but some medieval chroniclers claimed that Richard heard a rumor about treasure being hidden in the castle.Start of the SiegeRichard I, the Lionheart, King of England, by Merry-Joseph Blondel, 1841. Source: Westminster AbbeyWhen Richard arrived with his army at the castle on March 26, 1199, they found that its defenses were weak. Just a few men loyal to Viscount Aimar V were defending the walls and they were no match for Richards battle-hardened warriors. The viscount himself was too far away to relieve the garrison and Philip Augustus signed a temporary peace agreement with Richard. In addition to the English knights and archers that accompanied Richard, some French and Flemish mercenaries took part in the siege.The siege ultimately lasted several days. Richards army had a lot of experience laying siege to fortified castles. They brought the necessary equipment to break down the walls and the front gate. Additionally, English archers had a reputation as some of the best in any medieval European army, especially when using longbows. Nonetheless, the 40 defenders within the castles walls put up a tough fight, firing crossbow bolts at the Anglo-Norman attackers. They prevented several attempts to get through the front gate.In medieval sieges, it was common for armies to attempt to break through the front gate with a battering ram after deluging the castle walls with rocks launched from trebuchets. If the attempt to break through did not succeed, the besieging army could wait until the garrison ran out of food or water. The risk in this case was that if another army came to relieve the castle, it could spell doom for the besieging force. This did not happen to Richards army, however.Death of the LionheartRichard being hit with a crossbow bolt during the siege. Lithograph by Harry Payne, 1920. Source: MeisterdruckeBy the third day of the siege, the Anglo-Norman army was close to breaking through the walls. Repeated attempts to break down the gate compromised the integrity of the garrison. As was customary, Richard rode in front of his men as they prepared to enter the castle, braving crossbow bolts fired at him.According to accounts of the battle, Pierre Basile, a boy in the garrison, fired several crossbow bolts at Richard, who dodged most of them. After a couple of tries, Basile managed to hit Richard in the neck with a crossbow bolt, seriously wounding him. He rode back to one of the tents where surgeons were helping wounded men. Some of the nobles accompanying his army immediately placed into a bed with several surgeons attending him. An attempt to remove the bolt failed and Richard struggled with septicaemia over the next several days.As the English overran the castle, Basile was captured and brought to the king, expecting to be executed. It is reported that he told the English that he lost two brothers during the siege and killing Richard was personal. Surprisingly, Richard, who had once ordered the massacre of Muslim prisoners during the Third Crusade, ordered the boy spared. Even so, some French mercenaries in Richards army flayed the boy after his capture. Within 12 days of being wounded, Richard died on April 6, 1199, in the presence of his mother, Eleanor of Aquitaine.Aftermath of the SiegeKing John signing the Magna Carta in the presence of several nobles. Print by Joseph Martin Kronheim, 1868. Source: Wikimedia CommonsUpon Richards death, he was buried at Fontevraud Abbey alongside his father King Henry II and was succeeded as king of England and ruler of the Angevin empire by his brother John. John was unpopular with much of the English nobility and he faced threats from different rivals. While John was recognized as king in England, much of Richards continental empireespecially Anjou and Normandyleaned toward supporting Arthur of Brittany, the teenage son of their late brother Geoffrey. This dynastic dispute plunged the Angevin holdings into instability.Philip II broke the temporary truce he had made with the English and quickly took advantage, invading Angevin territories and supporting Arthurs claim. Under Johns weak and inconsistent leadership, the English crown would ultimately lose most of its French possessions over the following decade. This helped set the stage for the start of the Hundred Years War in 1337.Richards death also had symbolic consequences. Though often absent from England during his reign, Richard had been admired for his martial prowess and leadership during the Crusades. His death marked the beginning of the decline of the Angevin Empire, and his brother Johns ineptitude and heavy-handed rule would spark rebellions, culminating in the sealing of the Magna Carta in 1215. However, the noble revolts against John were in part the result of anger at the crown for Richards expensive wars.The Legacy of Richards Death in Popular CultureChlus Castle following renovation in 2019. Source: Chteau Chlus-Chabrol via Wikimedia CommonsRichard the Lionheart has long occupied a legendary place in popular culture, celebrated as the ideal medieval warrior king. His exploits during the Third Crusade, particularly his battles against Saladin, captured the imagination of chroniclers and later writers, cementing his image as a valiant warrior and defender of Christendom. Over the centuries, this reputation has often overshadowed the more complex realities of his reign, including his long absences from England and his burdensome taxation to fund military campaigns.In literature, Richard is frequently portrayed as a noble hero. He appears in Sir Walter Scotts Ivanhoe as a gallant figure who returns in disguise to rescue his kingdom from the villainy of Prince John. This romantic depiction became a cornerstone of the Robin Hood legend, where Richard is the benevolent monarch who restores justice after his brothers misrule. Films and television shows have embraced this trope, such as the 2010 movie Robin Hood, which shows Richard leading the sack of Chlus.The Lionheart moniker itself has become synonymous with courage and leadership, invoked far beyond historical circles. Though historians now take a more nuanced view of his reign, acknowledging his administrative negligence and costly wars, Richards cultural legacy endures. He remains one of the most iconic figures of medieval Europe, symbolizing the enduring allure of chivalric valor, noble kingship, and the romantic ideal of the Crusader hero.

0 Comentários

0 Compartilhamentos

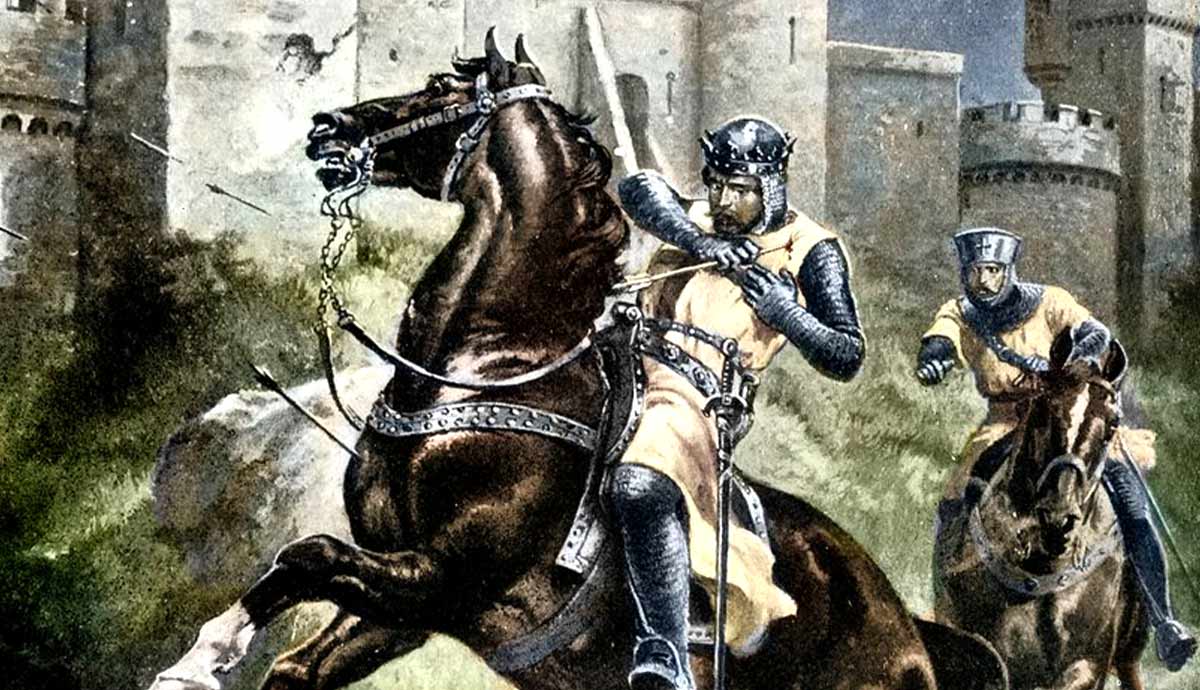

26 Visualizações