WWW.THECOLLECTOR.COM

Why January 1 Became New Years Day after Centuries of Calendar Wars

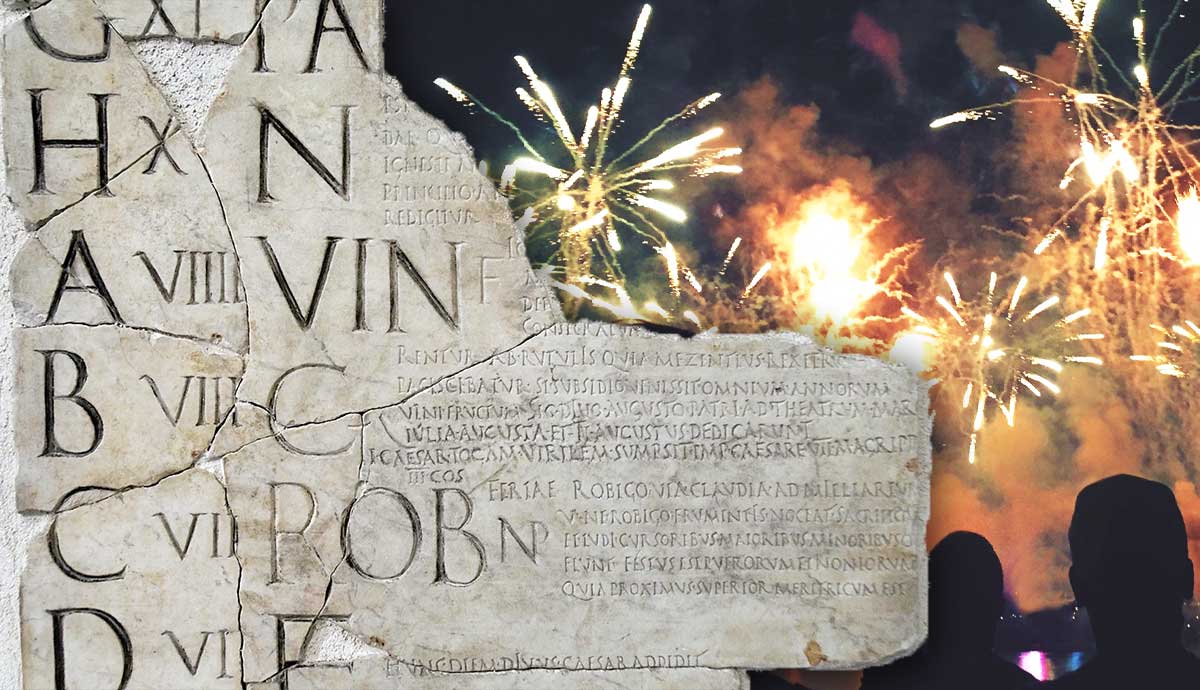

Today, the fact that January 1 marks the beginning of the year may seem a truth universally acknowledged. At the stroke of midnight on January 1, people exchange well wishes and kisses, toasting the start of a new year. However, it has not always been that way. Indeed, people have been changing the way used for marking time for centuries, drawing up different calendars to better respond to their needs. In the Western world, the origin of the New Year festival can be traced back to ancient Rome. Lets delve into the history that has led us to celebrate the beginning of the new year on January 1.Ancient New Years Days: Agriculture & WorshipDrawing of the god Marduk after a relief from about 1099/1082 BCE. Source: Store Norske LeksikonAncient civilizations usually followed the agricultural rhythm of preparing the soil and harvesting the crops to mark time. In an act of worship that echoed the worlds creation and celebrated the cyclical nature of life, people held New Year festivals in the spring, when the land began to stir, showing signs of renewal. So, after the inactive winter months, a new cycle of planting and harvesting could begin.In ancient Mesopotamia, for example, the Babylonians celebrated the Akitu festival, marking the beginning of a new year, after the vernal equinox in March, when the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers flooded, depositing the fertile silt on the soil. The festival revolved around the recitation of the Enuma Elish, the creation epic celebrating the sun god Marduks victory over the disruptive powers of chaos.Water was also a key seasonal factor in ancient Egypt, where the year began on the first day of the month of Thoth (September), the god of wisdom and knowledge. The Egyptians divided the year into three seasons that followed the agricultural cycle: Inundation (Akhet), Emergence (Peret), and Harvest (Shemu). In Europe, the Celts also structured their way of marking time around the agricultural seasons. Where the land and weather allowed more for cattle raising than cereal cultivation, cattle herding usually marked the annual cycle.The Roman Republican Calendar: From 10 to 12 MonthsFragments of the Fasti Praenestini, a calendar annotated by the Roman grammarian Verrius Flaccus (ca. 55 BCE 20 CE), photograph by Marie-Lan Nguyen. Source: Wikimedia Commons/Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, RomeThe agricultural cycle, with its seasonal rhythm, also served as the basis for the earliest Roman calendar. Traditionally attributed to Romulus, the legendary founder of Rome, it was probably developed from the Greek lunar calendar, which in turn was derived from the Babylonian one.According to this early way of marking time, the year began in March (Mars, the god of war) and ended in December, for a total of 10 months and 304 days. The two other winter months, when the farmers did not work in the fields, were not counted, resulting in a gap of 61 days. Traces of this Roman lunar calendar are still visible today: September, from the Latin septem, literally means the seventh month, October (octo) is Latin for eighth, November (novem) for ninth, and December (decem) for tenth.Relief depicting the Roman King Numa Pompilius, by Jean Guillaume Moitte. Source: Wikimedia Commons/Louvre Museum, ParisThen, as reported by Livy, during his reign, Numa Pompilius, the second king of Rome, altered the original calendar, adding two months and introducing January as the first month of the year. Known as Januarius by the ancient Romans, January was named after Janus, the god of beginnings, often depicted with a double-faced head.As the moons cycle (month) is approximately 29.5 days, the Roman civic calendar was about 10 days shorter than the solar year. As a result, it regularly fell out of sync with the seasons. To solve the synchronicity issue, the Romans occasionally added an extra 27- or 28-day-long month called Mercedonius.Over time, however, the calendar became too confused. The fact that the College of Pontiffs, the council responsible for regulating religious worship, often decided whether to insert the extra days for political reasons did not help matters. Indeed, the Pontifex Maximus regularly shortened or extended the terms of magistrates and public officials by tweaking the calendar.In 46 BCE, when Julius Caesar was declared dictator, there was a three-month gap between the lunar calendar and the seasons. As a result, that year, the calendar harvest arrived well before farmers had collected their annual crops. Harvest festivals did not come in summer nor those of the vintage in the autumn, complained Suetonius in his The Twelve Caesars.The Julian CalendarHead of Julius Caesar, author unknown, ca. 30-20 BCE. Source: Vatican MuseumsTo reorder the hopelessly confused civic calendar, in 46 BCE (known as ultimus annus confusionis, or the last year of confusion), Julius Caesar established a new, clearer dating system: the Julian Calendar.Based on the solar year instead of the lunar cycle, the reformed calendar was drawn up by the astronomer Sosigenes of Alexandria. Sosigenes retained January 1 as the beginning of the year, but introduced some changes to make the calendar more consistent, using the 365-day Egyptian solar year as his model.Instead of relying on the College of Pontiffs to intercalate (add) the missing days on political whims, Sosigenes divided the year into 12 months of either 30 or 31 days, except for February, which had 28 days in common years and 29 in a leap year. According to his calculations, the solar year had 365 days. In 46 BCE, during the transition between the two different dating systems, 90 days were added, making the year 445-day long.As the Roman Empire extended its control over the Mediterranean region, the people under Roman rule took on the custom of celebrating the Kalendae (Kalends, or the first day of the month) of January as the beginning of the new year. On New Years Day, in Rome and the provinces, people exchanged greetings, well-wishes, and gifts known as strenae, usually figs, honey-cakes, and dates. Over time, the celebrations became wilder, with people taking to the streets dressed up as animals, gods, or a different gender.New Years Day in the Middle Ages: A Pagan Festival?Annunciation, by Leonardo da Vinci, ca. 1472. In the Middle Ages, many Christian countries celebrated New Years Day on the Feast of the Annunciation (March 25). Source: The Uffizi, FlorenceIn the 5th century, after the fall of the Roman Empire in the West, many regions of Europe replaced January 1 as the beginning of the new year with dates more aligned with the leading religion of the time: Christianity. By then, Christian leaders had already voiced their disapproval with what they perceived as a pagan tradition. In the 4th century, for example, John Chrysostom, the later archbishop of Constantinople and Church Father, condemned the Kalends of January as an immoral festival.According to Chrysostom, not only was giving gifts with the expectation of getting something in return unpious, but the rowdiness associated with January 1 also went against Christian values. The whole year will be fortunate for you, not if you are drunk on the new-moon, but if both on the new-moon, and each day, you do those things approved by God, Chrysostom admonished. The fact that Christian priests addressed this matter, however, is itself proof that many Christians still celebrated the Kalends of January.In the Middle Ages, then, the tradition of welcoming the new year on January 1 gradually fell out of use. Some countries, like England, replaced it with March 25, the Feast of the Annunciation, or the commemoration of the angel Gabriels visit to the Virgin Mary, announcing that she would conceive Jesus Christ. In other places, the beginning of the new year was moved back to December 25.By the 16th century, it became clear that the Julian Calendar could no longer be relied upon to set the correct dates for the most important Christian feasts, starting from Easter. It was time to draw up a new dating system.The Gregorian CalendarPortrait of Pope Gregory XIII, by Bartolomeo Passarotti, ca. 1586. Source: Wikimedia Commons/Friedenstein Castle, Ghota, GermanyThe synchronization problem between the Julian Calendar and the solar year was due to a slight miscalculation error. Indeed, Sosigenes year was a bit more than eleven minutes longer than the Earths orbit around the sun. As a result, the Julian Calendar gained an extra day every 128 years.By the mid-1500s, the gap between the Julian year and the solar year had amounted to ten days. To amend the error, in 1582, Pope Gregory XIII, assisted by a team of mathematicians and astronomers, introduced a new calendar with the papal bull Inter gravissimas (In the gravest concern). Named after him, the revised dating system advanced the date by ten days, so that October 4 was followed by October 15 that year. The Gregorian Calendar also introduced a more accurate method of calculating leap years and restored January 1 as the start of the new year.The Italian states, Spain, Portugal, and other European Christian countries immediately welcomed the Gregorian Calendar. Many Protestant regions, however, refused to adopt a calendar devised by the pontiff, a strong supporter of the Counter-Reformation. As a result, between 1582 and the mid-18th century, Europeans not only followed two calendars, but also celebrated New Years Day on different dates.January 1 as New Years DayPeople watching a firework display on New Years Day, by IrisImages. Source: iStockDespite the initial calendar wars, a manifestation of the religious divide in 16th-century Europe, more and more countries gradually adopted the Gregorian Calendar. Among the first were the German Protestant states, which started using the new dating system in 1699.Great Britain and its colonies followed suit only 53 years later, when the Calendar (New Style) Act, also called an Act for regulating the Commencement of the Year, and for correcting the Calendar now in use, decreed the official adoption of the Gregorian Calendar. By then, many people had already taken up the habit of celebrating New Years Day on January 1 instead of March 25.Today, while most countries have adopted the Gregorian Calendar, a few still use the Julian Calendar or a modified version. Others use the Gregorian Calendar for secular matters while retaining a different one for religious purposes. There is currently a 13-day discrepancy between the Julian and Gregorian calendars.

0 Comentários

0 Compartilhamentos

23 Visualizações