WWW.THECOLLECTOR.COM

7 Facts About the Second Continental Congress (1775)

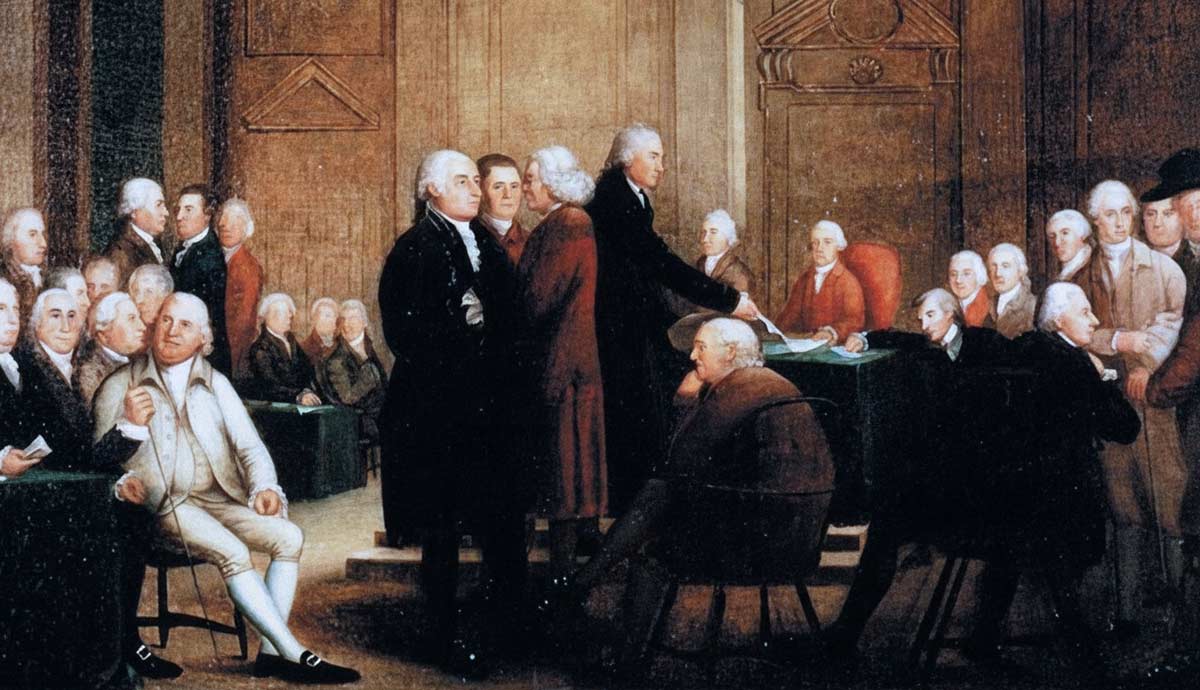

Gathering in May 1775, the Second Continental Congress arrived in Philadelphia after colonial militia clashed with British troops at the battles of Lexington and Concord. They selected George Washington as commander-in-chief, trying to unify militias into a singular army with a capable leader. Despite sending the Olive Branch Petition in a last-ditch effort at peace, Britain refused to compromise. Over the following months, the Congress acted as a makeshift government. By July 1776, they took their boldest step, declaring independence.1. It Began After the Battles of Lexington and ConcordHand-drawn map depicting the battles of Lexington and Concord and the siege of Boston, MA. 1775. Source: Library of CongressThe Second Continental Congress met in May 1775, just a few weeks after the first shots of the American Revolution were fired in Massachusetts. News of those battles at Lexington and Concord spread quickly, fueling both excitement and anxiety among the American colonists.Initially, many of them still hoped to find a middle ground with Britain rather than commit to outright rebellion. They believed some sort of diplomatic solution might still be possible if only the Crown realized how serious the colonies were about defending their rights. However, following the events in Massachusetts, the delegates understood there was no turning back.Some, like John Adams, felt it was time to prepare for a wider conflict, while others held onto the hope that King George III would see reason. Regardless, the Second Continental Congress found itself forced to balance calls for peace with the urgent need to protect the colonies from what was looking more and more like a war.2. Washington Became Commander-in-Chief of the ArmyGeorge Washington in military dress, by Charle Peal Polk, 1790. Source: The MET, New YorkOne of the most significant decisions the Second Continental Congress made was appointing George Washington to lead the newly formed Continental Army. At the time, the colonies didnt have a unified military force, just local militias that had been fighting in places like Massachusetts. Delegates wanted someone who could bring these militias together and present a united front against the British.Washington, already a well-regarded figure from the First Continental Congress and a respected officer in the British regulars, appeared at the sessions in his military uniform, signaling his readiness to serve. He was selected not just for his experience from the French and Indian War, but also because he was a Virginianan important factor in showing that this was not just a New England fight. By choosing a leader from the South, the Congress underscored that the colonies stood together as one.Washington himself seemed almost reluctant, aware of the immense responsibility he was taking on and the amount of work he had ahead of him. Yet once appointed, he rode north to Massachusetts to take command, beginning a leadership role that would define his legacy and the Revolutions direction.3. They Tried One Last Time to Reason With the KingThe Olive Branch Petition, 1775. Source: Library of CongressDespite the growing tension, the Second Continental Congress was not fully ready to abandon peace. In July 1775, the delegates drafted what became known as the Olive Branch Petition, a final appeal to King George III that tried to patch things up. They professed their loyalty to the Crown and asked for a stop to the escalating hostilities. They hoped it might persuade the king to rein in Parliament and find a reasonable compromise.Some members, like John Dickinson of Pennsylvania, firmly believed reconciliation was still possible and that independence should only be a last resort. However, others were skeptical of Britains willingness to meet them halfway.By the time the petition reached London, the situation had deteriorated too far. King George III refused to even receive the document, declaring the colonies to be in open rebellion. That rejection proved a turning point. Many delegates who had clung to the notion of peace realized there might be no other option left but to stand and fight.4. It Functioned Like an Early GovernmentThe formation of the Continental Army under the command of General George Washington, proposed by John Adams at the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia on June 10, 1775. Source: Wikimedia CommonsThe Second Continental Congress was not just a gathering of delegates, it essentially acted as the national government for the colonies during the early years of the Revolution. Without a formal constitution or centralized authority, the Congress took charge of everything from raising armies to managing finances. They printed continental currency to pay soldiers and tried to keep the economy stable in uncertain times. They also handled foreign relations, reaching out to other countries in the hope of gaining support against Britain. This made sense, given there was no other body with the power to make such decisions.Each colony had its own legislature, but the conflict required a unified approach. The Congress even set up committees to oversee different areas, like diplomatic missions or military supplies. While it faced plenty of criticismsome felt it lacked the legitimacy of an elected assemblythis body was, in many respects, the glue holding the colonies together. And with so much responsibility on their shoulders, the delegates found themselves juggling crisis after crisis.5. They Took Steps to Form Alliances AbroadMemorial to French soldiers who fought in the American Revolution, North Burial Ground, Providence, Rhode Island. Source: Wikimedia CommonsAs the war began, the members of the Second Continental Congress knew they needed more than just the passion of local militias to stand against the might of the British Empire. So, they began sending emissaries overseas, most notably to France, hoping to secure financial aid, weapons, and possibly even troops to not only fight but train the immense amount of raw recruits. Figures like Benjamin Franklin played a huge role here, using charm and diplomacy to court the French King at Versailles.Congress members understood that Britain had powerful enemies in Europe who might be happy to see the empire taken down a notch. Building these alliances was risky work, though. If the colonies failed to break free, they would be left in serious debt or under foreign influence. Still, the Congress forged ahead, creating committees tasked with negotiating treaties and securing loans from a variety of nations eager to see England defeated.These efforts would pay off in a big way when France finally agreed to an alliance in 1778, tipping the balance of power and giving the Continental Army the additional resources it desperately needed. Without these international connections, the war for independence would have likely had a very different outcome.6. They Did Not Immediately Declare IndependenceThomas Paines Common Sense, 1776. Source: Library of CongressBy early 1776, the idea of breaking away from Britain began to gain ground within the Second Continental Congress. The battles at Bunker Hill and elsewhere had shown that this was not just a minor dispute but a full-scale war. Pamphlets like Thomas Paines Common Sense stirred the public mood, arguing that sticking with Britain went against the ideals of the Enlightenment, a major influence on the colonial sentiment of the time.Influential voices in Congress, including John and Sam Adams, urged a clean break. Others were more hesitant, worried about losing trade ties and facing the wrath of the worlds most powerful nation. But as Britain clamped down harder, neutrality no longer felt possible. Slowly, colonial legislatures told their delegates to vote for independence if the topic came up.By June 1776, Virginia proposed a motion for separation, one of the last holdouts. A small committee, including Thomas Jefferson, was tasked with drafting a formal Declaration of Independence. This build-up of pressure and debate at the Second Continental Congress laid the groundwork for July 4, 1776.7. They Adopted the Declaration of IndependenceThe Declaration of Independence, 1776. Source: Wikimedia CommonsThe climax of the Second Continental Congress came on July 4, 1776, when delegates officially adopted the Declaration of Independence. Crafted primarily by Thomas Jefferson, the document laid out the colonies problems with King George III and boldly declared that they had the right to dissolve their ties with Britain based on the Enlightenment ideal of a peoples right to decide their own government.The Congress spent days debating the wording, making revisions, and ensuring each colony could stand behind it. On July 2, they voted for independence, and on July 4, the final text of the Declaration was approved. By signing it, the delegates essentially put their lives on the line, risking charges of treason if the rebellion failed.As word of the Declaration spread, celebrations erupted, complete with readings and the tearing down of British symbols. While the Declaration of Independence inspired colonists and remains a cornerstone of American identity, it was just the beginning of a challenging fight for freedom that would go on for years to come.

0 Σχόλια

0 Μοιράστηκε

21 Views