ALLTHATSINTERESTING.COM

How Todays Most Popular Thanksgiving Foods Made It To The Dinner Table

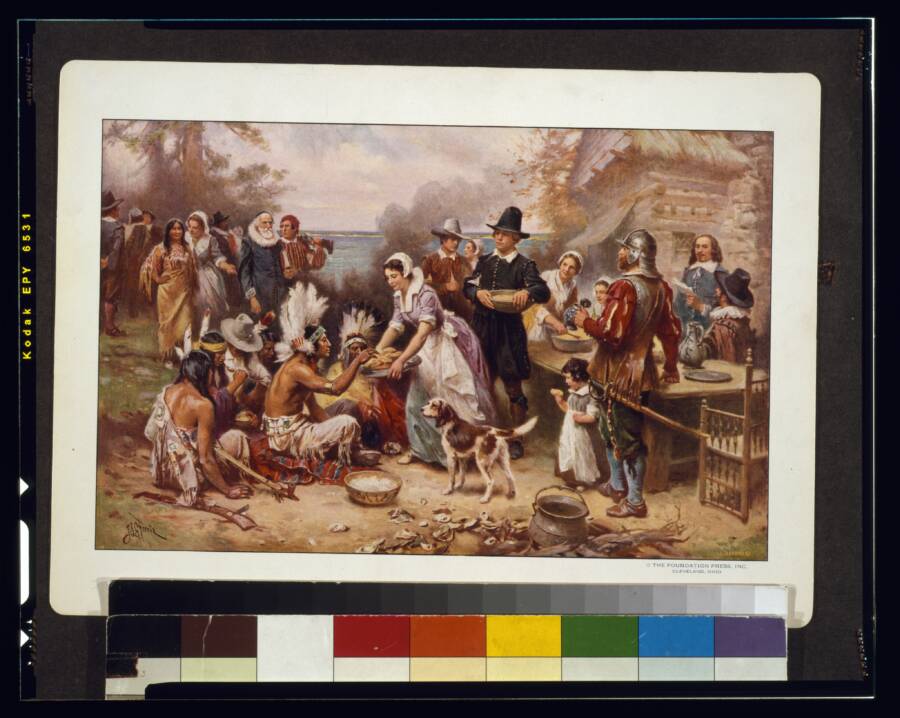

Every fourth Thursday in November, millions of Americans gather around tables laden with turkey, stuffing, cranberry sauce, and pumpkin pie. These Thanksgiving foods have become so synonymous with the holiday that its hard to imagine the annual feast without them. Click here to view slideshowYet the meal we recognize today bears only a passing resemblance to that shared by the Wampanoag people and English colonists in 1621. Most of the Thanksgiving foods we associate with the holiday didn't debut at that three-day celebration in Plymouth. Instead, they developed gradually over the centuries, influenced by regional preferences, agricultural changes, cookbook authors, marketing campaigns, and the contributions of diverse immigrant communities. And so, what began as a local harvest celebration eventually became a national holiday with an increasingly standardized menu. Above, look through photos of vintage Thanksgiving celebrations. And below, learn more about the origins of your favorite Thanksgiving foods.The First Thanksgiving In 1621: A Large Harvest CelebrationThe gathering that would later be referred to as "the first Thanksgiving" was, in reality, a harvest festival that shared little with our contemporary celebration beyond its spirit of gratitude. When approximately 50 English colonists and 90 Wampanoag people gathered in Plymouth in autumn 1621, they weren't following a prescribed menu or establishing an annual tradition. They were simply sharing a meal after a successful harvest, drawing from whatever foods were abundant and available in their coastal New England environment.The centerpiece of that meal was almost certainly not turkey, or at least not turkey alone. Wild fowl featured prominently, as colonist Edward Winslow noted in a letter that December that Governor William Bradford had asked men to hunt birds for the occasion: "[O]ur harvest being gotten in, our governor sent four men on fowling, that so we might after a more special manner rejoice together, after we had gathered the fruit of our labors." While wild turkey may have been among the birds, the colonists likely brought back mostly ducks, geese, and swans. Waterfowl would have been plentiful along the coast and easier to hunt than wild turkey. Winslow also wrote that the Wampanoag contributed five deer to the feast, meaning venison likely dominated the table as much as any bird.The meal would have been heavy on protein and notably lacking in many Thanksgiving foods we consider essential today. For instance, there were likely no mashed potatoes, as potatoes hadn't yet become a staple crop in North America. And while cranberries grew in the region, the colonists had little sugar, and thus no way to make a sweet sauce out of the fruit. And without wheat or butter, pumpkin pie couldn't have appeared in the form we know today. Library of CongressJean Leon Gerome Ferris' depiction of the first Thanksgiving, painted circa 1912.However, the Pilgrims and Wampanoag people did probably dine on pumpkins and squashes that were roasted whole in embers or stewed.What they did eat reflected the bounty of the season and the collaborative nature of the harvest. Corn appeared in various forms possibly as cornbread or porridge. Seafood was also a major part of the meal. As Winslow wrote: "[O]ur bay is full of lobsters all the summer, and affordeth variety of other fish; in September we can take a hogshead of eels in a night, with small labor, and can dig them out of their beds, all the winter we have mussels... at our doors: oysters we have none near, but we can have them brought by the Indians when we will."Native fruits and nuts, including walnuts, chestnuts, and perhaps dried berries, rounded out the meal. The Thanksgiving food was likely seasoned with herbs but lacked the black pepper and cinnamon we've come to associate with holiday cooking.For nearly two centuries after that 1621 gathering, Thanksgiving remained a sporadic, regionally varied affair. Communities held harvest celebrations, but they occurred at different times and featured whatever local tradition and availability dictated. Southern tables might have featured ham or seafood, while frontier families made do with wild game. There was no single "Thanksgiving meal" because there was no single, unified Thanksgiving holiday. The transformation into the celebration as we know it today began in earnest in the mid-19th century and was driven largely by Sarah Josepha Hale, the editor of the influential Godey's Lady's Book.How Thanksgiving Foods Transformed Over The CenturiesHale campaigned for years for Thanksgiving to become a national holiday, writing editorials and letters to governors and presidents, requesting that the last Thursday in November be set aside to "offer to God our tribute of joy and gratitude for the blessings of the year," according to the Old Farmer's Almanac.Public DomainA Winslow Homer engraving depicting Thanksgiving dinner that was printed in Harper's Weekly in November 1858.She also published recipes and menu suggestions that helped standardize Thanksgiving foods across the country. When President Abraham Lincoln finally proclaimed Thanksgiving a national holiday in 1863, Hale's vision of the ideal feast had already taken root in the American imagination.Turkey's rise to dominance on the Thanksgiving table came from several factors. The bird was large enough to feed a gathering, distinctly North American, and unlike chickens or cows not useful for eggs or milk, making it practical to slaughter for a feast. By the late 19th century, turkey farms were emerging, and the bird was becoming more affordable and accessible, all while cookbook authors and women's magazines reinforced turkey as a centerpiece of the Thanksgiving meal. The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw other modern staples solidify their place on the menu.Cranberry sauce evolved from a regional preserve into a national standard, especially after the 1912 invention of canned cranberries made them available year-round and coast-to-coast. Sweet potatoes, often served with marshmallows in a combination that emerged in the 1920s, became particularly popular in the South and eventually spread nationwide. Green bean casserole, meanwhile, didn't exist until 1955, when a Campbell's Soup Company employee created it as a way to promote cream of mushroom soup.Stuffing evolved from simple bread-and-herb mixtures to countless variations incorporating oysters, sausage, cornbread, chestnuts, and other regional ingredients. And mashed potatoes became standard as potatoes themselves became an American staple crop. Pumpkin pie finally achieved the form we recognize thanks to industrialization providing affordable sugar and spices. Canned condensed milk (introduced in the 1850s) and canned pumpkin (commercially available by the 1920s) made its preparation far easier.Of course, people across the United States and Canada have continued to innovate Thanksgiving foods based on their own family traditions or dietary restrictions, introducing alternatives like tofurkey. Even then, the idea of a Thanksgiving dinner is instantly recognizable and a far cry from the more sporadic harvest celebrations that preceded the holiday's formal induction. Still, whether we serve grandma's secret stuffing recipe or experiment with new fusion dishes, we're participating in the same ongoing evolution that transformed deer and eel into turkey and green bean casserole, showing how Thanksgiving food traditions have changed over time. After reading about the mouth-watering history of Thanksgiving foods, look through our vintage photographs from the Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade. Then, check out some of the weirdest Thanksgiving ads from years past.The post How Todays Most Popular Thanksgiving Foods Made It To The Dinner Table appeared first on All That's Interesting.

0 Kommentare

0 Geteilt

24 Ansichten