WWW.THECOLLECTOR.COM

How the Suez Canal Bridged Two Worlds

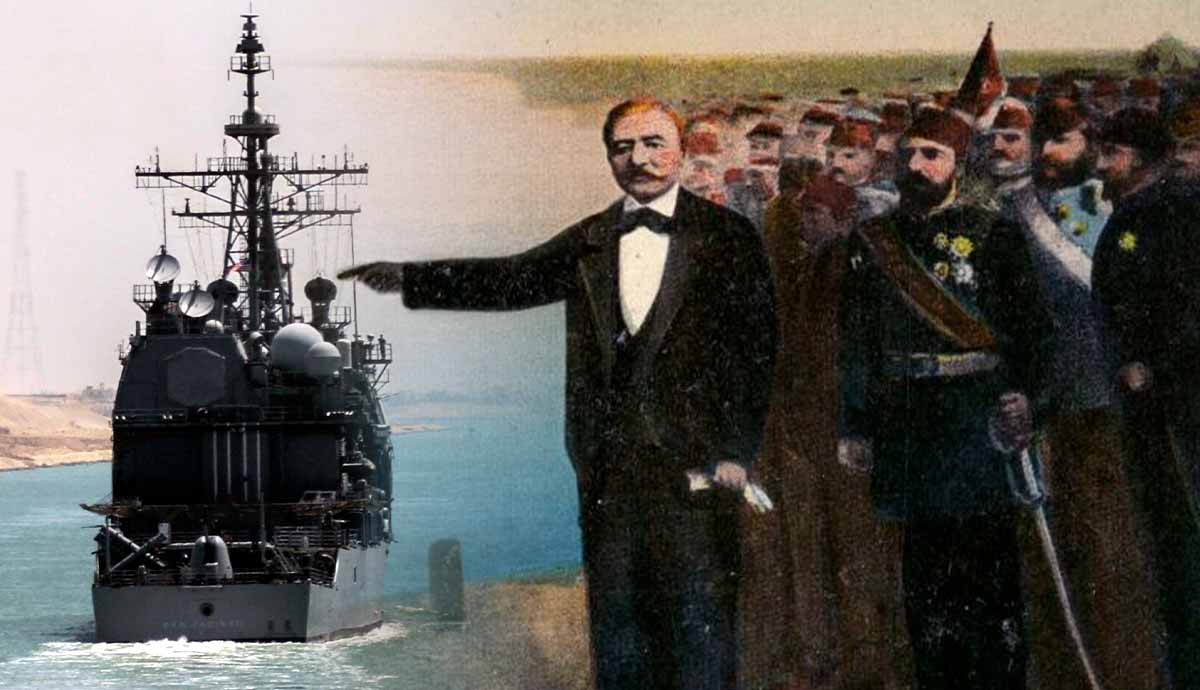

On April 25, 1859, French diplomat Ferdinand de Lesseps officially launched an engineering project he had envisioned since the 1830s: the piercing of the isthmus of Suez, a land bridge connecting the African continent with Asia. De Lesseps and the engineers involved in creating the Suez Canal sought to establish a faster trade route between Europe and the Indian Ocean. On that day, around 150 picketers gathered in Damietta, a port city in northern Egypt, and began excavating the land separating the Mediterranean and the Red Sea. Slowed by political conflicts, a cholera epidemic, and an initial lack of labor power, the construction of the Suez Canal lasted ten years.The Suez Canal in Ancient TimesStatue of Pharaoh Necho II. Source: Rijksmuseum, AmsterdamThe picketers who gathered on the northern shore of the Nile in 1859 were not the first workers to excavate the land between the river and the Red Sea. Ancient Greek historian and geographer Herodotus reported that Pharaoh Necho II, who ruled Egypt from 610 BCE to 595 BCE, began the making of the canal into the Red Sea, which was finished by Darius the Persian.The ancient waterway passed through the valley of Wadi Tumilat and the Bitter Lakes to reach the Red Sea. Necho II likely launched the project to facilitate the growing trade in the delta of the Nile. According to Herodotus, a hundred and twenty thousand Egyptians perished in the digging of it. However, an unfavorable oracle led the pharaoh to cease the operations.In his Library, Greek historian Diodorus (active in the time of Julius Caesar and Augustus) wrote that Darius also stopped the digging of the ancient canal for he was informed by certain persons that if he dug through the neck of land he would be responsible for the submergence of Egypt, for they pointed out to him that the Red Sea was higher than Egypt. According to Diodorus, the Ptolemy dynasty finally finished the canal, installing an ingenious kind of a lock to prevent floodings.Today, it is believed that the waterway mentioned by Herodotus and Diodorus dates back to the 1850s BCE when Egyptian pharaohs began building irrigation channels between the Nile and the Red Sea. After his military campaigns in the area, Roman Emperor Trajan extended the canal for trade purposes. After falling into disuse during the Byzantine period, the ancient waterway was finally closed around 760 CE, when the Abbasid caliphs sought to prevent the rebelling cities of Mecca and Medina from using it for supplies. Toward the end of the 18th century, when France occupied Egypt, Napoleon Bonaparte saw the remains of the ancient Suez Canal.Dreaming of a Canal: From Napoleon Bonaparte to Ferdinand de LessepsBonaparte et son tat-Major en Egypte by Jean-Lon Grme, 1863. Source: ArtReviewIn the 15th and 17th centuries, as several European countries sought to establish their dominance in trade with the East, the maritime Republic of Venice and France speculated about the possibility of redigging the ancient Canal of the Pharaohs. However, they never carried out the hypothetical schemes.In 1798, when Napoleon Bonaparte conquered Egypt, European vessels had to circumnavigate the African continent to reach the Indian Ocean. Hoping to reduce Great Britains presence in India and the Middle East, the future French emperor proposed creating a faster route between Europe and the Indian Ocean by restoring the canal dug by the Egyptian rulers. A waterway connecting the Mediterranean and the Red Sea would serve the double purpose of expanding international trade and securing the French monopoly of the surrounding area.Shortly after his successful campaign in Egypt, Bonaparte visited the isthmus of Suez and the location of the ancient channel. Upon his return, he sent a team of scientists and engineers to survey the area and lay the groundwork for his ambitious endeavor.The preliminary studies results, however, disappointed the French general. Head engineer Jacques-Marie Lepre, commissioned to design the future canal, overestimated the difference in the Mediterranean and Red Seas altitude levels. Because of his incorrect calculation, Lepre advised against building a direct connection between the two bodies of water, warning that during the high tide, the Red Sea rose 10 meters (33 feet). Thus, it would overflow onto the Nile and the surrounding areas.Ferdinand de Lesseps. Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New YorkDespite widespread doubts about its feasibility, the idea of piercing the isthmus of Suez did not disappear, especially among the French scientific community. In 1833, a group of engineers traveled to Egypt to conduct a new survey of the land between the African continent and Asia. The young scientists belong to the Saint-Simone sect, a society following social theorist Henri de Saint Simones beliefs on the key role of science and technology in modern society. Prosper Enfantin, the leader of the Saint-Simonians, was passionate about the old project of creating a canal in Suez. Skeptical about the accuracy of the former studies of the isthmus, Enfantin founded the international Socit dtudes du Canal de Suez (Suez Canal Study Group) in 1846.The group disputed Lepres calculation, declaring that the Mediterranean and Red Sea had almost identical altitudes. In particular, Luigi (Alois) Negrelli, a civil engineer of Italian origins employed at the court of the Austrian emperor, introduced the idea of connecting the two bodies of water with a canal starting on the northern shores of the Nile and ending directly in the Red Sea. Faced with the opposition of Great Britain and the Khedive (viceroy) of Egypt, Abbas Pasha, the efforts of the study group came to nothing in the early 1850s.In the same period, the idea of excavating a canal in Suez also caught the attention of Ferdinand de Lesseps, the former French consul to Cairo. During his post in the Egyptian city, de Lesseps became acquainted with Said Pasha, a son of the ruling Viceroy. In 1854, when Abbas Pasha died, the French diplomat shared his scheme for a canal between the Mediterranean and the Red Sea with his friend. On November 30, the new Viceroy granted de Lesseps the concession to establish a company to build the waterway.Great Britains Opposition and an Engineering FeudLord Palmerston, a fierce opponent of the Suez Canal, 1850s. Source: University of Southampton Special CollectionsUpon obtaining the concession from the Viceroy, Ferdinand de Lesseps began lobbying for the Suez Canal Company throughout Europe, calling for entrepreneurs and politicians to support his project. While the plan to create a faster trade route was met with interest in several countries, Great Britain firmly opposed de Lesseps endeavor. In December 1854, de Lesseps complained to an acquaintance that British officials stationed in Constantinople had even begun pressuring the Sultan to withhold his approval for the canal. Canvass opinion in England, wrote de Lesseps, heaven helps those who help themselves.In 1855, the French diplomat himself went to London in an effort to persuade the British government that a direct connection between the Mediterranean and the Red Seas would be beneficial to the countrys commercial and colonial interests.I have received sympathy and promises of assistance, and even of active co-operation, from a large number of gentlemen of influence in politics, science, trade, and commerce, reported de Lesseps in a letter addressed to Napoleon III. However, Lord Palmerston, the prime minister, remained firmly opposed to the idea of a canal, comparing it to the many bubble schemes which are palmed upon gullible capitalists.Arabia, William Henry F. Plate, 1847. The map shows the isthmus of Suez before the creation of the maritime canal. Source: Qatar Digital LibraryOver the following years, the Suez Canal became one of the major political issues in the United Kingdom, with businessmen, newspapers, scientists, and members of Parliament intensively debating the project. Lord Palmerston unwaveringly claimed that the de Lesseps scheme was incompatible with the standing policy of England on foreign affairs. In particular, the prime minister feared the Suez Canal would weaken the integrity of the Ottoman Empire, which the British government had always sought to maintain. He also believed what he dismissively called the French ditch would foster French influence in the area. During the parliamentary debate of July 1857, Palmerston claimed that the Alexandria-Cairo railway, commissioned by Abbas Pasha to Robert Stephenson, was much more beneficial to British interests.Panoramic view of the isthmus of Suez, 1855. Source: Gallica, Bibliothque nationale de FranceDuring the session, the British engineer supported Lord Palmerstons view on the canal, emphasizing its skepticism about the projects feasibility. A year later, Stephenson attacked Luigi Negrellis proposal for the waterway, disputing his findings in another parliamentary debate on the Suez Canal. The Austrian engineer responded with an article in the sterreichische Zeitung (Austrian Newspaper). A heated war of words between the two experts ensued, with Stephenson and Negrelli challenging each other in a series of open letters published in the Austrian newspaper and the Times. Both engineers died before they could mend their feud.The Suez Canal CompanyThe Suez Canal Company headquarters in Egypt. Source: Egypt TodayDespite the British governments hostility and lobbying against the canal, de Lesseps wasted no time in laying the groundwork for the excavation of the isthmus of Suez. In 1855, he created an International Scientific Commission to assess all previous proposals for the waterway between the Mediterranean and the Red Sea. In November of the same year, he accompanied some engineers of the commission to Egypt, where they conducted extensive geological studies. In 1857, after several debates, the Suez Commission officially adopted the plan designed by Luigi Negrelli.In 1858, after a second concession from the Egyptian viceroy, Ferdinand de Lesseps was finally able to establish the Compagnie Universelle du Canal Maritime de Suez (Suez Canal Company). The two acts of concession granted the company control of the waterway for 99 years after the end of the excavation. Then, Egypt would obtain full ownership of the canal. In November, de Lesseps offered 400,000 shares of the company. Each share cost 500 Francs. While thousands of French citizens opted to invest in the diplomats project, the portions offered to Austria, Britain, Russia, and the United States remained largely unsold. To avoid delaying the start of the works, Said Pasha had to buy the rest of the shares. The Viceroy took a large loan from France to cover the cost.1859-1869: A Ten-Year ProjectWorkers at a Suez Canal job site, Justin Kozlowski, 1869. Source: Gallica, Bibliothque nationale de FranceWorks on the Suez Canal officially began on the northern shores of the Nile River on April 25, 1859. In the early phases, the excavation was carried out by picketers, who dug the land and the bed of the lakes with pickaxes and baskets. Working conditions were extremely hard, with the men standing naked in the water for hours, dredging mud from rivers and lakes.The construction of the waterway drew many job seekers to Egypt. While some men and women employed by the Egyptian government and the Suez Canal Company received some form of compensation, many joined the excavation under the threat of violence. Despite de Lasseps claim that workers [came] running to our worksites, on many excavations sites, forced laborers toiled with their pickaxes as foremen threatened to whip those deemed too slow.However, in the first years, the operations at the Suez Canal slowed down because of the opposition of the British government rather than labor troubles. Indeed, the British ambassador in Constantinople managed to stop all operations when he revealed to the Egyptian authorities that the Sultan had yet to approve of the project. Only the direct intervention of Napoleon III solved the stalemate, allowing the Suez Canal Company to resume the excavation.In 1865, a cholera epidemic further delayed the construction of the canal. In the last years of operations, however, the use of mechanical dredgers and shovels sped up the excavation. In August 1869, ten years after the first pickaxe blow, the Mediterranean and the Red Sea were finally connected. Workers had to dig 73 million cubic meters (97 million cubic yards) of mud and soil to achieve that result. The Suez Canal Company had spent more than double the original budget raised for the project.The Inauguration of the Suez CanalFerdinand de Lesseps and Ismail, the viceroy of Egypt, during the inauguration of the Suez Canal. Source: Gallica, Bibliothque nationale de FranceThe canal officially opened with a solemn ceremony on November 17, 1869. Thousands of dignitaries, emperors, and leaders gathered in Egypt to participate in the boat procession through the newly built Suez Canal. The LAigle, the vessel of French Empress Eugenie, was the first ship to travel through the waterway. Firework displays and evening balls entertained the guests. The Egyptian Viceroy had also commissioned Italian composer Giuseppe Verdi to write an opera for the inauguration. However, the Franco-Prussian War and the Siege of Paris delayed the shipping of the scenery for the performance. Thus, the opera house staged Verdis Rigoletto instead of the scheduled premiere of Aida.A US missile cruiser navigating the Suez Canal, 2013. Source: US Department of DefenseDuring the first two years after its opening, the number of ships passing through the canal was smaller than the companys projections. The width and depths of several spots made navigation difficult for larger vessels. Between 1870 and 1884, about 3,000 ships got stranded. In 1876, when the waterway underwent extensive improvement, the daily traffic rose consistently. Ironically, the majority of the vessels using the Suez Canal displayed a British flag. In 1875, when the Egyptian government faced a financial crisis, British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli bought the Viceroys shares of the Suez Canal Company.Shortly after its opening, the Suez Canal became one of the most important maritime routes. In 1956, after the so-called Suez Canal Crisis, Egypt gained control of the waterway.

0 Comentários

0 Compartilhamentos

183 Visualizações