WWW.THECOLLECTOR.COM

The Story of the Nicaraguan Revolution & Counterrevolution

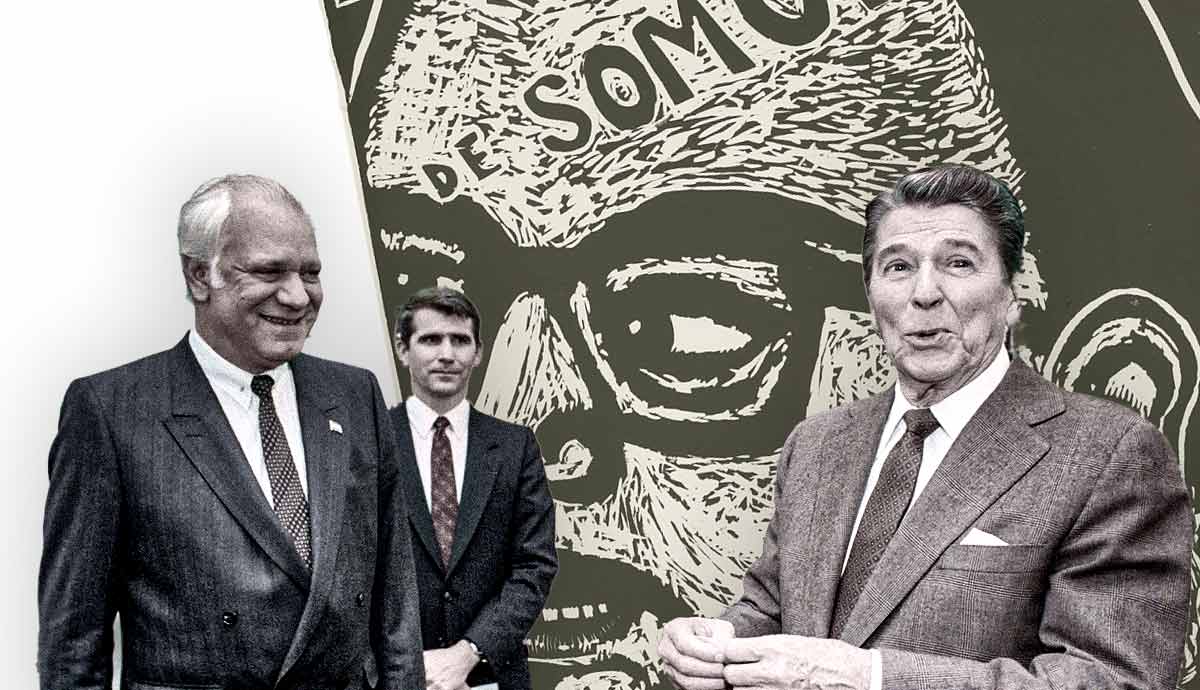

In the mid-20th century, much of Latin America was ruled by wealthy autocrats or military regimes. These countries powerful northern neighbor, the United States, funneled economic and military support their way, turning a blind eye to human rights abuses and corruption so long as it meant communist forces were kept at bay. But the successful 1959 Cuban revolution sparked hope in the regionanother way was possible, and opposition movements began popping up, promising a more egalitarian, prosperous future for all.Autocracy and Imperialism: A Revolution Takes ShapeNicaraguan President Anastasio Somoza welcomed to the House of Representatives by Speaker of the House William B. Bankhead. Washington DC, May 8, 1939. Source: Library of CongressBy the 1970s, when a viable opposition movement first began to take shape in Nicaragua, the country had been ruled by the Somoza family for decades: first, the father, Anastasio, who came to power in 1937, then his eldest son, Luis, and finally his younger son, also Anastasio. The family spent its time in power gobbling up the countrys land, granting political favors to the wealthyincluding US businessesand enriching themselves. The country also retained US support by providing a base from which the CIA could carry out operations in neighboring countries.Throughout the familys rule, a veneer of democracy was retained, with opposition parties allowed political space, but elections were rigged, and outright dissent was quickly quashed. It was no surprise when the revolutionary fervor that had begun to take root in the region with the success of the Cuban revolution made its way to Nicaragua as well, with initial pro-labor, anti-imperialism groups forming in the 1960s. The group that would come to take center stage, the Frente Sandinista de Liberacin Nacional (Sandinista National Liberation Front, FSLN), was founded in 1961 by Carlos Fonseca, Silvio Mayorga, and Toms Borge, three Nicaraguan exiles living in Honduras.The FSLN would ultimately comprise three separate factions with the same goaloverthrowing the dictatorship in favor of socialist reformsbut differing ideas about how best to achieve it, with various tactics employed throughout the 1970s.At War With the SomozasManagua earthquake, 1972. Photo by Oriol Maspons. Source: Museu Nacional dArt de Catalunya, BarcelonaAfter a 1972 earthquake destroyed much of Managua and international aid disappeared in the Somoza familys pockets, the tide began to turn. The Somozas blatant theft of earthquake aid was too much, even for some of the countrys elites, who also faced new emergency taxes implemented for disaster aid and reconstruction. Though many Nicaraguans didnt necessarily agree with the socialist or communist policies of the countrys revolutionary groups, a coalition movement slowly began to coalesce around their common ground: it was time for the Somozas to go. Strikes and demonstrations began in earnest while the FSLN sought recruits in the countryside.One key moment in the fight came when the FSLN succeeded in holding a group of wealthy government officials hostage in 1974, presenting the Somoza government with a series of demands for their release. Once their demands were met and the hostages released, Somozas response was an indiscriminately violent crackdown designed to root out guerrillas that terrorized the rural population. The attacks horrified the Catholic Church, which brought worldwide attention to the atrocities of the Somoza regime.International attention brought a brief reprieve, but violent anti-terrorism campaigns, martial law, and suspension of the free press continued on and off throughout the decade. The more the government cracked down on dissident groups and sympathizersperhaps most notably Joaqun Chamorro, a popular newspaper editor Somoza had assassinatedthe larger the opposition movement grew, while the National Guards human rights abuses drove the regimes foreign allies to distance themselves.The FSLN Comes to PowerEnough Somozas. Long live a free Nicaragua. Anti-Somoza poster. Wilfred Owen Brigade, 1976. Source: Library of CongressBy the end of the decade, the countrys National Guard could no longer counter the revolutionary army. The FSLN had solidified a broad base from nearly all sectors of Nicaraguan society and was receiving additional support from the USSR, Cuba, and other countries in Latin America. It controlled nearly the entire country, except for the capital, Managua, and had established a provisional government, the Junta de Gobierno de Reconstruccin Nacional (Government Junta for National Reconstruction).Meanwhile, military repression combined with nationwide strikes and capital flight had devastated the economy and driven away foreign and military aid to the Somoza regime. In July 1979, FSLN guerrillas surrounded the capital, and the Somozas fled.Nicaraguas initial post-insurgency government was a coalition of FSLN leaders and other non-Sandinista opponents of Somoza, a measure designed to bolster the image of the new regime as democratic and assure the Nicaraguan people that the diverse interests of all were represented. The new government, not in a position to burn bridges, sought diplomatic relations with countries at all points on the political spectrum, including the US.The FSLN had inherited a country in ruins: 50,000 people had been killed during the war, 600,000 were homeless, and the economy was devastated. Rebuilding it was a top priority, and, counter to the groups Marxist ideological roots, private sector representatives were appointed to handle the essential economic tasks of renegotiating debt and securing aid.Mural in Nicaragua depicting the liberators of Latin America and founders of the FSLN. Source: Cordelia Persen, FlickrEqually important, however, was retaining the groups support base, the rural and urban poor who believed in the radical social transformation project the FSLN had promised. Leadership quickly moved to adopt some of the most prominent measures it had been advocating over the previous decade, including the nationalization of the land the Somozas had accumulated, which was distributed to farming cooperatives. Spending on health and education increased dramatically, vaccination campaigns were undertaken, health centers and schools were built, thousands of new teachers were trained, and the new government received an award from UNESCO for its literacy crusade.Despite the inclusive nature of the new regime, in a relatively short time, it became apparent that the FSLN was truly in charge, with Sandinistas taking over the highest positions in leadership and holding the majority in representative organizations. As a result, some more moderate elements dropped out of the coalition. Without these moderate elements to act as guardrails, the FSLN government slowly adopted more radical measures that drew the condemnation of the countrys middle and upper classes as well as key foreign powers. Land and assets were confiscated from the wealthy and business leaders while the government sought closer ties with socialist countries, and democratic elections were deemphasized in favor of popular organizations providing feedback and input to the coalition government.Counterrevolution: Opposing the OppositionPresident Ronald Reagan with Adolfo Calero, a Nicaraguan Democratic Resistance (Contra) Leader, and Oliver North, April 1985. Source: National ArchivesBacklash to the FSLN came almost immediately from the remaining Somoza supporters and elites, as well as the moderates who felt locked out of governing by the Sandinistas. Of greatest concern, however, was the counterrevolutionary army, the Contras, that quickly sprung up among former National Guard membersbacked by a rich, powerful ally.US President Jimmy Carter had withdrawn support from the repressive Somoza regime in the late 1970s, helping to solidify the FSLNs victory. Once they took power, he worked to develop a relationship with the Sandinistas and sought Congressional approval for aid that he believed would help ensure the new regime did not turn further leftward in its fight for social justice but maintained a mixed economy and a cooperative relationship with the US. Carters time in office, though, was nearly at an end by the time the FSLN achieved victory.After the US presidential elections in 1980, the Sandinistas quickly drew the ire of Carters successor, Ronald Reagan, by reportedly aiding revolutionaries in El Salvador, and US aid to Nicaragua was quickly terminated. Within his first year, Reagan had determined that the Sandinistas were also displaying unacceptable Marxist and totalitarian tendencies, and he became determined to remove them from power.Nicaraguas first post-Somoza President, Daniel Ortega, at the UN, July 1986. Source: Library of CongressAn outright war was out of the question, so instead, Reagan opted for a low-intensity conflictcomprising military, economic, political, and psychological pressuresdesigned to undermine the government and its popular social reform projects. Primary among these was his decision to finance, arm, and train the emerging Contra army.Having apparently made an enemy of the new US administration, Nicaragua held presidential and parliamentary elections in 1984 with the hope of gaining support among democratic governments. Though boycotted by right-wing parties and condemned as rigged before they even happened by the US, Nicaraguans turned out in droves to vote, and the FSLN candidate, Daniel Ortega, a prominent figure in the revolutionary movement and existing governing coalition, won handily. The FSLN also held a majority in the National Assembly, ensuring their economic and social reform projects could continue.The elections did little to legitimize the government outside the country, and the war with the Contras deepened. As the Contras launched more and deadlier attacks around the country, the Sandinistas were forced to dedicate increased spending to defense rather than the social justice and poverty reduction programs it had made the hallmark of its victory. Meanwhile, thanks to a US embargo, it was simultaneously relying more heavily on trade and financing from Cuba and the Soviet Union, the very countries the US wanted to stop the new regime from emulating. As opposition grew, the Sandinistas regime looked increasingly like its predecessors, rescinding press freedoms and cracking down on opposition organizations.The Revolution Comes to an EndVioleta Chamorro celebrates her victory in the presidential race, 1990. Source: La PrensaEarly on, the FSLN proved that it could indeed better the lives of Nicaraguans. However, as the counterrevolution progressed, the Sandinistas ability to improve or even protect lives rapidly deteriorated. When Hurricane Juana hit in 1988, leaving 180,000 people homeless, the war-ravaged country and flailing Sandinista government could not cope, and support plummeted further as elections drew near.In 1990, Violeta Chamorro, widow of murdered La Prensa editor Pedro Joaquin Chamorro and one-time member of the post-Somoza junta, ran for president as part of an anti-Sandinista coalition and won in elections determined to be free and fair by nonpartisan international observers. The coalition, orchestrated by the US, had given the Nicaraguan people a choice: the Sandinistas or an end to the war.Its noteworthy that the Sandinistas could have employed a number of tactics to remain in power, as seen so often in neighboring countries. They might have delayed elections because of the circumstances or refused to recognize the elections as valid because of US interference. Instead, they accepted the outcome of the elections and allowed a peaceful transition of power, becoming an opposition party in a participatory democracy at least for a few election cycles. The Sandinistas, still under the leadership of Daniel Ortega, won the presidency again in 2006. Ortega remains in power today.Additional Sources:Skidmore, Thomas E and Smith, Peter H. Modern Latin America. Oxford University Press, 2001Prevost, Gary and Venden, Harry E. Politics of Latin America: The Power Game. Oxford University Press, 2002

0 Commentarios

0 Acciones

224 Views