WWW.THECOLLECTOR.COM

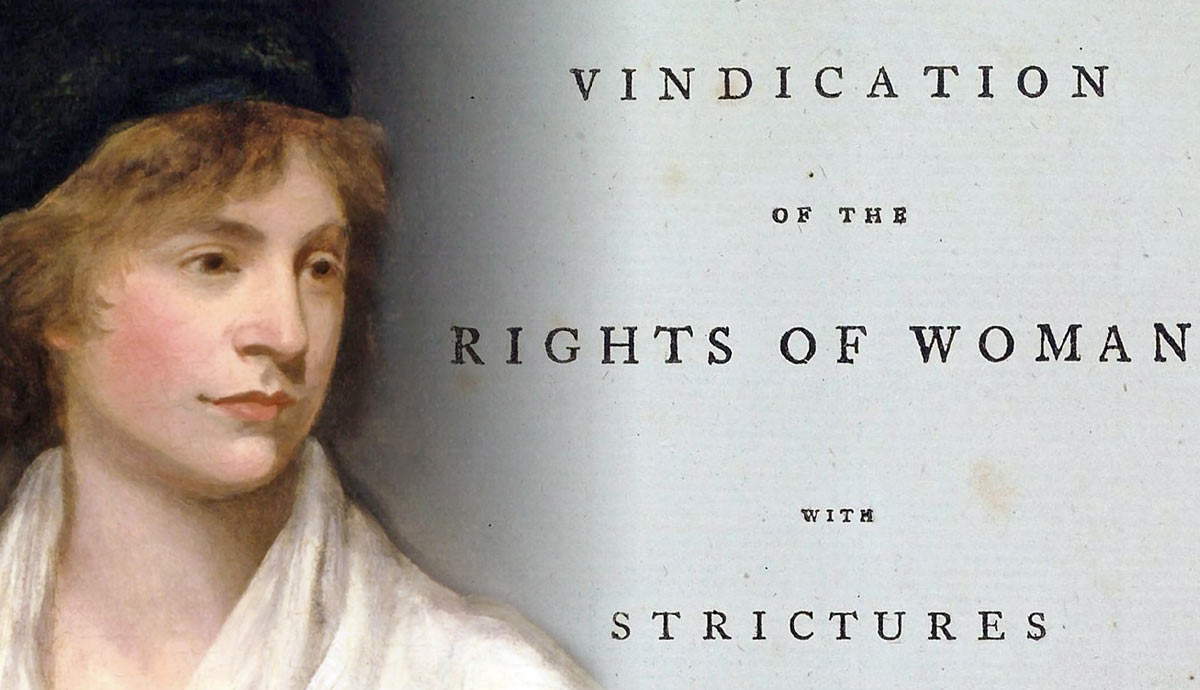

Mary Wollstonecraft, The Woman Who Laid the Foundation for Feminism

The life of Mary Wollstonecraft was more than just the writing of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, although this is what has made her an enduring figure in the history of feminism. Her biography is just as exciting and ahead of its time as that short but hugely influential 18th-century text. Mary Wollstonecraft was a woman who lived out her principles, especially her passionate devotion to liberty and her belief in the power of womens genius.Mary Wollstonecraft: The Enlightenment WomanAn Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump, by Joseph Wright of Derby, 1768. Source: Wikimedia Commons/National Gallery, LondonMary Wollstonecraft, born in 1759, grew up during what we now call the Age of Enlightenment. In London, where she was born, Samuel Johnson published his dictionary and would soon issue a complete edition of Shakespeares works and Lives of the Most Eminent English Poets. Adam Smith was theorizing about moral sentiments, such as sympathy.Across the Channel, Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Voltaire were publishing philosophical novels and treatises. Denis Diderots Encyclopdie began to appear from 1751, and the Encyclopedia Britannica followed in 1771: a world of knowledge was opening up rapidly.But not for women, as Wollstonecraft found. The idea of co-education was still some way off, and girlseven those lucky enough to be born into wealthy familiesreceived a far less stimulating education than boys. They were merely equipped with accomplishments, things like embroidery, a little music (but not too much), and housework.Wollstonecraft was born into a family which often had to move around the country due to financial instability, and neither of her parents was especially interested in her education because (by her own account) her father was prone to violent, often drunken outbursts, during which he was physically abusive towards her mother.First page of Thoughts on the Education of Daughters, by Mary Wollstonecraft, 1787. Source: Wikimedia Commons/Eighteenth Century Collections Online; with The Governess, by Rebecca Solomon, c. 1851. Source: Wikimedia Commons/Art Renewal CenterAs a young adult, Wollstonecraft gained some educational experience, first as a ladys companion in Bath and later as co-founder of a school in Newington Green, north London. Both experiences would inform how she wrote about womens education, not just in her most famous work, but in its precursor, her first book, Thoughts on the Education of Daughters (1787). This was primarily an advice manual, reciting conventional wisdom around contemporary educational norms. However, it also contained seeds of her later critiques of the practice of limiting womens education to so-called feminine matters.The Young RadicalThe Nightmare, by Henry Fuseli, 1781. Source: Wikimedia Commons/Detroit Institute of ArtsAlso at this stage, Wollstonecraft showed signs of the radical behavior for which she would later become notorious. When her younger sister, Eliza, married and had a child, Mary recognized the signs of what we would now call postpartum depression, and could see that the marriage between Eliza and her husband was over. Late-18th-century divorce laws in Britain severely limited womens ability to leave a marriage for any reason whatsoever. Only with the passing of the Matrimonial Causes Act 75 years later, in 1857, did women gain the right to petition for divorce on the grounds of adultery, cruelty, or desertionand even then with difficulty.Mary, therefore, helped her sister secretly escape her husband and live apart from him, a decisive act that brought Eliza freedom at the cost of social ostracization. This was just one instance, along with setting up the Newington Green school in a Dissenting community (a separatist group who rejected the authority of the state and church in England), that showed Wollstonecraft beginning to move in radical circles.Mary Wollstonecraft, by John Opie, c. 1797. Source: Wikimedia Commons/National Portrait Gallery, LondonThese centered around the publisher Joseph Johnson, who was from a Dissenting background and applied these principles to his work, supporting and promoting thinkers who were critical of the establishment. Johnson was devoted to achieving political change through his publications, working with authors who argued in favor of religious tolerance, the American Revolution, and (even before Wollstonecraft came along, but especially once he became her publisher) womens rights.Also a legendary dinner host, Johnson would gather these liberal firebrands around his table in London, fostering a community which encouraged Wollstonecraft in her gradually awakening wish to become what she called the first of a new genus, that rare thing, a female author (Wollstonecraft, 2003, 139).Henry Fuseli, by James Northcote, date unknown. Source: Wikimedia Commons/National Portrait Gallery, LondonAt one of Johnsons dinners, Wollstonecraft met William Godwin, three years her senior, who was beginning to dip his toe into political criticism and philosophy. The meeting was not a great success. Having come to hear the exciting revolutionary Thomas Paine, who had galvanized America into finding freedom, Godwin found himself arguing with Wollstonecraft all night instead.She fared betterinitiallywith the Swiss painter Henry Fuseli, whose 1781 painting The Nightmare hung in Johnsons dining-room. The two were captivated by each others genius, and she quickly fell in love with Fuseli, despite knowing he had a wife. In a characteristically radical move, unfazed by social judgment, Wollstonecraft proposed that she live with Fuseli and his wife. Her experiences with both her parents and her sister Eliza had clouded her view of conventional marriage, and she sought arrangements that might prove more liberating. Fuselis wife, however, did not consider it liberating to share her husband with another woman, and the painter broke off contact with Wollstonecraft.Mary Wollstonecraft: The PamphleteerThe National Assembly taking the Tennis Court Oath, by Jacques-Louis David, 1791. Source: Muse National du Chteau, VersaillesDetermined to make a living as a writer, Wollstonecraft spent her late twenties contributing reviews and criticism to Johnsons Analytical Review and translating works from French and German into English. She was keenly interested in the more radical discussions among Johnsons circle, and in 1790 she found the perfect outlet for her literary and political fervor.In November, the politician and philosopher Edmund Burke published Reflections on the Revolution in France, a response to the events of 1789the storming of the Bastille and the fall of the Ancien Rgime in France. Burkes pamphlet discusses the populace as a body, extending the metaphor by asserting that it is naturallike the laws of biologyfor some parts of that social body to defer to others, that is, for civilians to worship their monarch. Contrasting France, in all its upheaval, with its neighbor, Burke celebrates Britains conservative stability, reiterating the idea of the nation as a body by claiming that the laws of succession are a healthy habit agreed upon mutually by the monarchy, the government, and the people.As radicals such as Wollstonecraft argued, Burkes idea of society as a contract was compromised by the fact that vast swathes of the populace had no means of agreeing to this contract, since the power to vote was limited to land-owning men over 21. Wollstonecraft immediately set to work on a response that would, as its title suggested, vindicate the part that all people have to play in society.Edmund Burke, by James Northcote (based on the original by Joshua Reynolds), 1770s. Source: Art UK/Royal Albert Memorial Museum & Art Gallery, Exeter, DevonA Vindication of the Rights of Men, written in a matter of weeks, is a defense of liberty and equality, and a point-for-point refutation of Burkes pamphlet. (The use of men in the title, she explains, is a concession to the fact that other writers of the day referred to the rights of men even though what they really meant was, as she puts it, the rights of humanity.) Wollstonecraft undertakes a methodical deconstruction of Burkes slavish paradoxes and, engaging with some of the most crucial terms in 18th-century philosophy, claims that both our reason and our emotion ought to lead us to the conclusion that hereditary privileges are unjust.Another important dichotomy Wollstonecraft invokes is the sublime and the beautiful, concepts which Burke himself had theorized in a 1757 treatise. Like reason and emotion, these terms had gendered connotationsthe overawing sublime was aligned with masculinity, while beauty was delicate and feminine. Using Burkes own language against him, Wollstonecraft constructs an argument that she would soon expand on in A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. Confining women to the realm of the beautiful hindered their development in every way, but especially morally, making it impossible for them to partake in politics, and ultimately injuring a huge portion of the social body.The Slave Ship, by J.M.W. Turner, 1840. Source: The Museum of Fine Arts BostonAs Wollstonecraft proves with her own rational critique of Burkes text, this equation of women with passivity and weakness is not innate, only socially enforced. It is entirely possible for women to make rational arguments. Moreover, Wollstonecraft also challenges Burkes other claims about innatenessparticularly the idea that it is natural for people to defer to social hierarchy.The French Revolution had provided the backdrop for Wollstonecrafts first political work, which was an instant success. Although published anonymously at first, it soon catapulted her to fame when the second edition carried her name. More responses to Burke followed in 1791, including Thomas Paines Rights of Man, and Wollstonecraft kept a keen eye on events across the Channel, particularly the ongoing debates about how women might fit into libert, galit, fraternit. She would soon travel to Paris to see the revolution in action for herself, but not before she had written the text that would truly make her name.A Vindication of the Rights of WomanTitle page of the first edition of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, by Mary Wollstonecraft, 1792. Source: Wikimedia Commons/New York Public LibraryTaking Wollstonecrafts best-known work out of context, it might be easily overlooked that the Rights of Woman sprang directly from its authors response to the French Revolution. However, the text was dedicated to Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Prigord, a statesman who had presented his plan of reforms to Frances National Assembly in 1791, including the recommendation that women remain at home while men participate in the public sphere, and that their respective educations prepare them for these roles. Wollstonecraft met Talleyrand in 1792 after the publication of Rights of Woman, and reiterated its call for him to reconsider this recommendation.This second Vindication combined Wollstonecrafts ideas from the first about societys oppression with her earlier opinions on girls education. Expanding the discussion of education to cover matters such as marriage, parenting, and health (mental, emotional, and physical), Wollstonecraft proves the integral place of womens rights in establishing a just, functional society, as the revolutionaries across the Channel were supposedly trying to do.Portrait of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, by Maurice Quentin de la Tour, late 18th century. Source: Wikimedia Commons/Muse Antoine-Lcuyer, Saint-QuentinMary Wollstonecraft begins her book by reflecting on Rousseau and his concepts of nature and civilization. She then argues that the weakness commonly attributed to women is not natural but a result of their education and upbringing. Male authors, from philosophers to conduct-book writers, have perpetuated the misconception that women are innately weak, which only compounds the problem: society is predicated on this misconception, so women begin to believe it of themselves.Thus, as Wollstonecraft admits, the women she has observed are weak, frivolous, and artificial, but only because they have been told they are. They are taught that the natural way of things is for them to be beautiful, which will smooth the path towards their main aspiration: marriage. As long as they can simulate all the behaviors associated with beauty in refined societydelicacy, feigned or unfeigned weakness, a little learning but not too much (the accomplishments Wollstonecraft had described in Thoughts on the Education of Daughters)they will be able to marry. This was no small matter at a time when women could not own property and were therefore financially dependent on male relatives, either fathers or husbands.Mary Wollstonecraft, by John Opie, 1790-91. Source: Wikimedia Commons/Tate Britain, LondonHowever, basing womens capacity for marriage only on their fulfilment of beauty, as Wollstonecraft argues, creates unequal marriages in which women are akin to slaves. She is conscious that the comparison to slavery is highly charged, given the abolitionist debates taking place in Britain at this time. Still, she insists that a system which doles out a limited education to women, so that they may enter into an extremely dependent legal arrangement with their husbands, is enforcing a kind of bondage.Rights of Woman was a rallying call. Several times, Wollstonecraft proclaims the need for a revolution in female manners. From this and the emphasis throughout the text on how languishing and ineffectual many women of the time had become, it might seem like Wollstonecraft was placing the onus on women to effect change. However, she recognized that meaningful change (which, remembering the pamphlets context in revolutionary politics, meant a total reorganization of society) could only come about through the collaboration of the sexes.Since men controlled the public sphere, dictated the laws, and swayed opinion on how boys and girls ought to be educated, it was for them to generously snap our chains, and be content with rational fellowship, instead of slavish obedience. This arrangement would benefit both men and women too: marriages would be more successful, children would be better brought up, and society as a whole would be more equitable.The Eyewitness to RevolutionUne Excution capitale, place de la Rvolution by Pierre-Antoine Demachy, 1793. Source: Muse Carnavalet, ParisWhen Wollstonecraft traveled to France at the end of 1792, she had the chance to put her ideas to the test. Was it possible for a rational woman, who had fought against the limitations placed on women in her time, to meet men on their level, to nurture relationships founded on mutual recognition of intellect and morality?Wollstonecraft was among several British people (along with Paine and the then relatively unknown poet William Wordsworth) who flocked to Paris in a wave of revolutionary fervor. By the time she arrived, however, this initial promise had given way to violence, and Wollstonecraft found herself unexpectedly moved by Louis XVIs trial and execution.Now stuck in limbo as increasing hostilities between Britain and France prevented her leaving, Wollstonecraft sought security by registering at the American Embassy as the wife of an adventurer turned diplomat (and, unbeknownst to Wollstonecraft, investor in slave ships), Gilbert Imlay. She was not Imlays wife, but she had fallen deeply in love with him and they had slept together. Wollstonecrafts personal life became a testing ground for the arguments she was making publiclythat women ought to be granted the same freedoms as men, and judged by the same standards of morality.Le Dernier banquet des Girondins, by Henri Flix Emmanuel Philippoteaux, c. 1850. Source: Wikimedia Commons/Museum of the French Revolution, VizilleBy 1794, Wollstonecraft was becoming disillusioned with post-Revolution France, not least because the triumphant Jacobins were no more inclined to treat women as equal citizens than the Ancien Rgime had been. Still unable to leave, she gave birth to Imlays child in May, a daughter named Fanny. Beyond this, however, her experiment in seeking a more equitable relationship between men and women was not bearing fruit. Imlay was unwilling to set up a home with Wollstonecraft permanently, and spent long periods away from her on business. Against the backdrop of these personal difficulties, Wollstonecraft nevertheless managed to write a historical account of what she had seen during her residence in France, An Historical and Moral View of the French Revolution (1794).Mary Wollstonecraft: The TravelerLandscape with Waterfall, by Allart van Everdingen, c. 1660-75. Source: The Wallace Collection, LondonA mixture of expediency and drive led to Wollstonecrafts next publication, the remarkable Letters Written During a Short Residence in Sweden, Norway, and Denmark (1796). Finally able to leave France after the fall of the Jacobins, she sought Imlay in London, but he was unwilling to rekindle their relationship and she was left suicidal.Though increasingly aware that he would not be faithful to her, she made a final attempt to prove her loyalty by traveling to Scandinavia to aid his business interests there. To make this journey alone, without Imlay, and with just their infant daughter and a maid, was highly unusualbut Wollstonecraft was by now well used to taking the radical path. Imlay ultimately responded to her loyalty by taking up with another woman during her absence.While traveling through Sweden, Norway, and Denmark, Wollstonecraft wrote 25 letters to Imlay, eventually published together in book form. The letters are remarkable not only for the personal circumstances behind them but also for the reflections on the self, society, and nature prompted by what Wollstonecraft sees on her journey.Wollstonecrafts observations do not aim at objectivity. Everything is colored by her feelings as an observer, informed by what is happening in her life then. As such, Letters is as much of a memoir as it is a travelogue. It even resembles the epistolary novel, comprised entirely of letters, and presents a narrative of increasing despair at Imlays faithlessness.A Lake in Norway, by Francis Danby, c. 1825. Source: Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon CollectionInfluenced by Rousseaus confessional writing, Wollstonecraft does not flinch from revealing how she feels at each turn to the reader. Also, returning to her reading of Burke, Wollstonecraft employs the concept of the sublime to discuss the landscapes she passes through. Her letters continually move between observations of, for instance, a roaring waterfall, with its incessant, oppressive current, and her own experience of oppression.Like her previous works, Letters contains philosophical reflections on the relationship between reason and emotion, the natural, and the imagination. In using nature as a stimulus for these thoughts, Wollstonecraft participates in the emerging Romantic movement. It was not until poets like Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge published their own work on man and nature that Romanticism was fully recognized. However, Wollstonecrafts Letters was a key influence for these poets (Holmes, 1987, p. 41), guiding a whole generation of soul-seeking wanderers.The Wife and MotherWilliam Godwin, by James Northcote, 1802. Source: Wikimedia Commons/National Portrait Gallery, LondonA turbulent test of her beliefs that women and men could form equal partnerships had left Wollstonecraft suicidal more than once. However, she was undeterred by her disappointments with Imlay. She maintained her principles and put them into practice again in 1796, when she came back into the orbit of a certain philosopher: William Godwin.Godwin later wrote that reading Letters, with its blend of keen observation and deep reflection, had made him fall in love with its author. He also fell in love with her through continued meetings in their shared literary circles. Like Wollstonecraft, Godwin had been immensely interested in the developments in France. However, the book he published as a resulthis seminal Enquiry Concerning Political Justicedid not directly refer to the events.Nevertheless, Political Justice was a critique of the same institutions that had come under fire both during the Revolution and in Wollstonecrafts writing: hereditary monarchy, property ownership, and marriage. Like Wollstonecraft, Godwin believed in the innate reason of the individual, and, therefore, the capacity of a collective to agree on the best form of government.Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, by Richard Rothwell. Source: Wikimedia Commons/National Portrait Gallery, LondonIt is debatable whether Wollstonecraft was against marriage altogether, or primarily in its contemporary form, and therefore would have been in favor had she been sure she was founding a new, equal version of it with someone who shared her views. Yet Godwin was this long-sought equal partner, and ultimately the two only married out of necessity. She became pregnant in late 1796, and to ensure the child would be legitimate, they married in March 1797. Although their more radical friends saw this as unnecessary deference to social norms, Wollstonecraft and Godwin maintained their commitment to reforming the institution of marriage by living in separate, adjoining houses in London.Tragically, however, the couples experiment did not last long. At the end of August, Wollstonecraft gave birth, and less than two weeks later, she died following a childbed infection. Godwin was inconsolable, and wrote to a friend: I firmly believe that there does not exist her equal in the world. I know from experience we were formed to make each other happy. I have not the least expectation that I can now ever know happiness again (Kegan Paul, 1876, chapter 10). Her child survived: not the son Godwin had hoped to call William, but a daughter named Mary after her mother.Mary Wollstonecraft: The Founding FeministSt Pancras Old Church, seen in 1815, engraved by Charles Pye from a drawing by John Preston Neale. Source: Wikimedia CommonsA year after Wollstonecrafts death, Godwin inadvertently damaged her reputation by publishing Memoirs of the Author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. To his mind, it was a tribute to his brilliant equal. However, to many readers, it revealed what only their friends had known before, that Wollstonecraft had pursued a married man, had had a child out of wedlock, and (as likely to cause shock as sympathy in this period) had attempted suicide more than once. It was many years before Wollstonecraft was recognized and appreciated for her writings, rather than judged for her private life.Her radical spirit lived on in her daughter, who was only 16 when she eloped with the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley (a hard to substantiate story claims that Mary and Percy first slept together at Wollstonecrafts grave at St. Pancras churchit is at least true that Mary visited there often and took Percy for walks in the churchyard). Two years later, during an infamous ghost story contest at the shores of Lake Geneva, Mary Shelley began writing the novel that would make her as much of a founder as her mother, but this time, the founder of the science fiction genre: Frankenstein.First pages of French translation of Maria, or the Wrongs of Woman, by Mary Wollstonecraft, 1798. Source: Rare Book Collections at Princeton University LibraryWollstonecrafts most substantial posthumous work is a good counterpart to her daughters novel. Maria: or the Wrongs of Woman was published in 1798, perhaps overlooked partly because Godwins memoirs had turned many reviewers against her, but partly also because it was so radical. Maria is an astounding tale of cross-class solidarity and dissent among women in an asylum: the servant Jemima, whose illegitimacy and precarious social position have left her open to abuse, and the upper-class woman Maria, who has fared little better despite a seemingly happy, respectable existence as wife of a prominent gentleman.The novel is remarkable not just for its horrifying portrayal of suffering, but for the way it acts as a continuation of Wollstonecrafts arguments in the non-fictional Vindication of the Rights of Woman. Neither of the female protagonists is protected from patriarchal abuse. Despite their wildly different circumstances, both fall victim to all the forms of mistreatment experienced by 18th-century wives: physical, emotional, and financial. Although unfinished, the fragments of Maria offer the greatest testament to the range of Mary Wollstonecrafts talents, as an author, a political thinker, and a galvanizing feminist philosopher.BibliographyBurke, E. (2005). The Works of the Right Honourable Edmund Burke, Vol. 03. Project Gutenberg edition, https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/15679/pg15679-images.htmlKegan, P. C. (1876). William Godwin: His Friends and Contemporaries, Vol. 1 by C. Kegan Paul. Henry S. King and Co.Holmes, R. (1987). Introduction. A Short Residence in Sweden, Norway and Denmark and Memoirs of the Author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. Penguin Books.Raymond, E. (2021). The Early Life of Mary Wollstonecraft. East End Womens Museum blog, https://eastendwomensmuseum.org/blog/2021/4/30/the-early-life-of-mary-wollstonecraftWollstonecraft, M. (1790). A Vindication of the Rights of Men. Printed for J. Johnson. WikiSource version, https://web.archive.org/web/20150906163640/https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/A_Vindication_of_the_Rights_of_MenWollstonecraft, M. (2002). A Vindication of the Rights of Woman. Project Gutenberg edition, https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/3420/pg3420-images.htmlWollstonecraft, M. (2003). The Collected Letters of Mary Wollstonecraft. Ed. Janet Todd. Columbia University Press.

0 Comentários

0 Compartilhamentos

185 Visualizações