WWW.THECOLLECTOR.COM

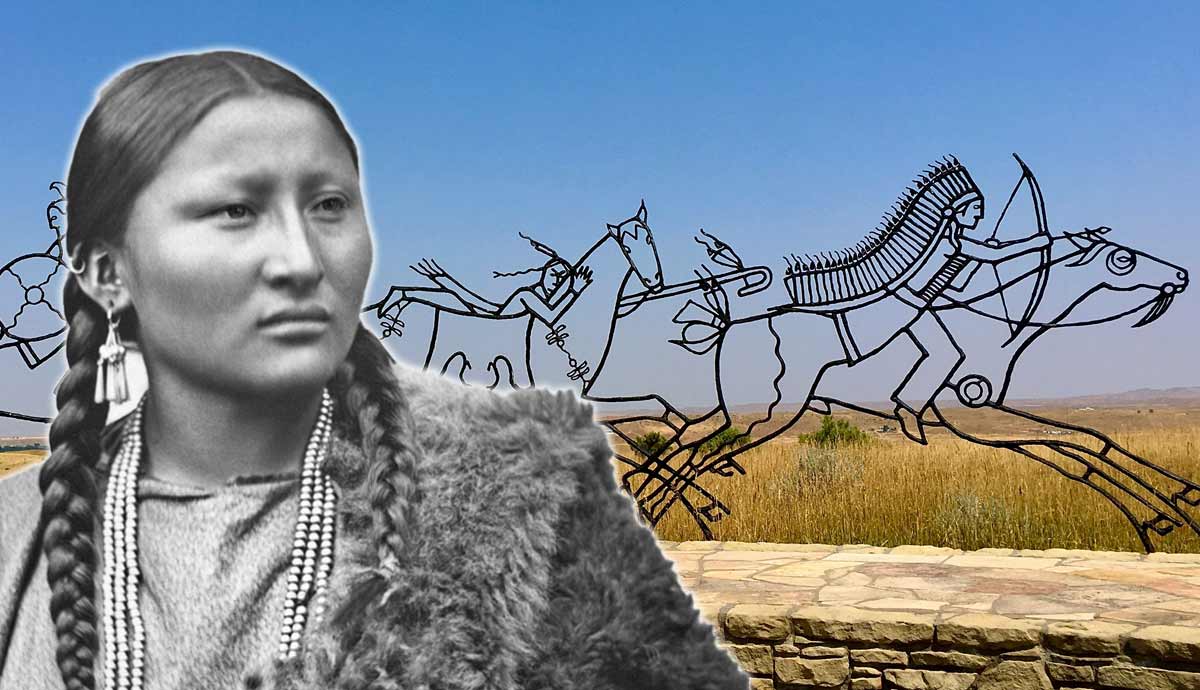

The Indigenous Women Who Fought at the Battle of Little Bighorn

The Battle of Little Bighorn is also known as Custers Last Stand. The name of Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer (1839-1876), who led the 7th Cavalry Regiment in the U.S. Army against a coalition of Native American tribes near the Little Bighorn River in Montana, will forever be linked to his defeat at Little Bighorn and to the humiliation of his persona. However, few people associate the Battle of Little Bighorn with the names of the hundreds of Native American chiefs and warriors who fought there. Even fewer remember the women who fought at Little Bighorn alongside Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse, and contributed to the defeat of George Armstrong Custer. Here are four of them.What Happened at Little Bighorn?Gathering of the Clans, painting by Jules Tavernier, 1876. Source: Fine Arts Museums of San FranciscoThe Battle of Little Bighorn was the direct result of the discovery of gold in the Black Hills, in present-day South Dakota. In 1868, with the Treaty of Fort Laramie, the American government established the Great Sioux Reservation, an area set aside for the Lakota people. Here they were promised they could live forever in peace, on land that would be theirs as long as grass grow, wind blow, and the sky is blue, as Jack Crabb (Dustin Hoffman) puts it at the end of Arthur Penns revisionist film Little Big Man (1970).The Great Sioux Reservation included the Black Hills. Under the leadership of Ulysses S. Grant (1822-1885), the 18th president of the United States, the American government attempted to persuade the Lakota to sell their lands, but they refused.Black Hills, photograph by Pamela Huber, 2020. Source: UnsplashOn June 25, 1876, the 7th Cavalry Regiment of the U.S. Army, led by George Armstrong Custer attacked an encampment of approximately 6,000 to 7,000 Lakota Sioux, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho along the Little Bighorn River in the Crow Indian Reservation in southeastern Montana. The exact number of people who died between June 25 and June 26 is uncertain. It is estimated that among Custers men, 258 were killed or died of wounds, including Custer himself and Canadian newspaper reporter Mark Kellogg. Of the casualties, 16 were officers and 242 were troopers.Estimates of Indigenous casualties range from 36 to 136, as reported by Lakota chief Red Horse in 1877, to some 300 Lakota and Northern Cheyenne. One of them was Hunkpapa Sioux One Hawk, who was the brother of Moving Robe Woman, one of the women who fought at Little Bighorn.General George Armstrong Custer, painting by Henry H. Cross, 1874. Source: Gilcrease MuseumAdditionally, on the Native American side, we should also remember six (unnamed) women and four (unnamed) children who were likely killed at the very start of the battle. The Battle of Little Bighorn continues to be one of the most extensively studied events in the history of the United States of America and Canada.Despite their significant victory at Little Bighorn, three thousand Teton Lakota moved into present-day southwestern Saskatchewan over the next few months, settling around Cypress Hills and Wood Mountain. In 1863, a group of Santee had already crossed the border following the Battles of New Ulm (or Minnesota Uprising), joining the Mtis around Upper Fort Garry, at the forks of the Red and Assiniboine rivers, in what is now Manitoba.Little Big Man wearing his beaded war shirt, photograph by William Henry Jackson. Source: Gilcrease MuseumThe Battle of Little Bighorn turned Indigenous leaders and warriors into legendary figures. Sitting Bull (or Tatka yotake), Crazy Horse (Take Witk), Little Big Man (Wiha Tkala), and Kicking Bear (Mat Wantaka) are just four of the manyNative American leaders who fought at Little Bighorn. Among them were also four women from different tribes, including the Hunkpapa Sioux, Oglala, Northern Cheyenne, and Arapaho, who fought alongside their husbands, friends, and relatives, andcontributed to changing the course of North American history.Moving Robe WomanSioux family, ca. 1850-1900. Source: Gilcrease MuseumDuring her (relatively) long life, Moving Robe Woman was known by many names. Among the Hunkpapa Sioux, the Lakota group she belonged to, she was called Tana Mni. Among non-Indigenous, she was known as Walks With Her Robe, Walking Blanket Woman, She Walks With Her Shawl, or simply Mary Crawler.The Dakota people have always been known by the name of Sioux among non-Indigenous people, which is an abbreviation of Nadouessioux, a French transcription of Nadowessi. In the language of the Ojibwa, Nadowessi translates as snake and enemy. The Dakota Nation is divided into three major groups: the Wihyena (comprising the Yankton and Yanktonai), the Santee Dakota (or Eastern Dakotas), and finally the Teton Lakota. The Hunkpapa Sioux, to which Moving Robe Woman and her beloved brother belonged, was one of the seven bands (or council fires) making up the Teton Lakota.Sioux Camp Scene, by Alfred Jacob Miller, 1858-1860. Source: The Walters Art MuseumThe word Hkpapa means Head of the Circle in Lakhota (or Laktiyapi) one of the three dialects of the Sioux language, which belongs to the larger Siouan family group. Moving Robe Woman, the daughter of Crawler (or Siohan), an important Hungpapa chief and warrior, and Sunflower Face was in her early 20s when she moved with her family from Grand River in South Dakota, where she was born, to Peji Sla Wakapa, or Greasy Grass, in what is now Montana. Among non-Indigenous Anglophones, Peji Sla Wakapa is known as the Little Bighorn.On June 25, 1876, the day of the battle, Moving Robe Woman was digging wild turnips with other girls when a warrior rode swiftly into the camp announcing that American soldiers under the command of Pehin Hanska were approaching. Reportedly, Moving Robe Woman jumped on her horse and rode in their direction with her father and other warriors.A Lakota beaded belt, which warriors would wear in battle, 1880-1890. Source: Brooklyn MuseumThe valley was dense with powder smoke, she recalled in 1931. I never heard such whooping and shouting. () There were Indians everywhereIt was not a massacre, but a hotly contested battle between two armed forces. Her brother, One Hawk, was killed in the initial attack, and she rode into battle with her face painted crimson and her hair braided, as a sign of mourning. She shot army interpreter Isaiah Dorman (1820-1876), the only African American killed at Little Bighorn, and killed another soldier with a knife. Some sources claim that it was Moving Robe Woman who killed Custer, repeatedly stabbing him in the back as Oglala Lakota warrior Fast Eagle held his arms.Pretty NosePretty Nose, photograph by Laton Alton Huffman, 1879. Source: Wikimedia CommonsThe Arapaho people believe that their ancestors once lived permanently in the Eastern Woodlands, in the western Great Lakes region along the Red River Valley. They likely occupied a large territory spanning contemporary Manitoba and Minnesota. Due to conflicts with the Ojibwe, they were compelled to migrate westward along the Platte and Arkansas rivers, in present-day Kansas, Nebraska, Colorado, and Wyoming. Here, they shifted from farming to buffalo hunting. Like other Plains people in the United States and Canada, they used to live in tepees, relied on horses for transportation and hunting, and traded buffalo products for the squash, beans, and corn that their ancestors once cultivated in the Eastern Woodlands. Since 1878, the Northern Arapaho have been residing with another group, the Shoshone, on the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming.Thunderhead, by Eugene Ridgely Jr. (also known as Niieihii Nooteihi), a member of the Northern Arapaho tribe from Ethete, Wyoming. Source: Museum of BoulderThe 1867 Treaty of Medicine Lodge established a reservation in Oklahoma for the Southern Arapaho, who had been living along the Arkansas River since the 1830s. The Arapaho shared the reservation with other bands of Southern Cheyenne, who referred to them as Hitanwoiv, People of the Sky. Arapaho warriors fought alongside the Cheyenne at Little Bighorn, and among them was a woman known as Pretty Nose.In a photograph taken by Laton Alton Huffman (1854-1931), three years after the Battle of Little Bighorn, Pretty Nose sits proudly in her elegant cloth dress and buffalo robe, with her hair braided and her hands adorned with rings. Another picture shows her with her little sister on her lap. Little is known about Pretty Noses life before the battle at Little Bighorn, much like many of the men and women who fought (and died) there.Arapaho parfleche bag with designs inspired by Whirlwind Woman, the mystical woman in Arapaho oral traditions, 1900. Source: Brooklyn MuseumMost of what we know about Pretty Noses life after the battle and her status among the Arapaho and Cheyenne comes from the words of one of her descendants, tribal leader and storyteller Mark Soldier Wolf (1928-2018).She was (likely) born around 1851 and reportedly died after 1952. In 1952, she was alive to see her 24-year-old descendant, Mark Soldier Wolf, return to the Wind River Indian Reservation after serving in the Korean War. Historians have therefore speculated that she was over 100 years old when she finally passed away. When she saw young Mark Soldier Wolf return to Wind River, she was working in a field. Upon seeing him, she started singing a war song in his honor. Wolf later reported that she was wearing beaded cuffs around her wrists, a testament to her status as a War Chief among the Arapaho of Wind River, among the men and women who fought at Little Bighorn.Buffalo Calf Road WomanCheyenne warrior on horseback wearing a stripe and blue shirt, long leggings, and two feathers on his head knocks his non-Indigenous enemy off his horse, 1890. Source: Brooklyn MuseumBuffalo Calf Road Woman, also known as Brave Woman, was a Northern Cheyenne warrior. Her people were close allies of the Arapaho since at least 1811, more than six decades before the Battle of Little Bighorn. Like the Arapaho, they had moved westward from the Great Lakes region to present-day North Dakota and Minnesota after conflicts with the Assiniboine during the 17th century. They then relocated from the Missouri River to the Powder River Country, in northeastern Wyoming, between the Black Hills and the Bighorn Mountains.Through their formal alliance with the Arapaho,the Cheyenne were able to expand their territory on the Great Plains in the 19th century. By the 1820s, the Cheyennes hunting territory extended from southern Montana through Wyoming, part of Colorado and Nebraska, including the Washita and Cimarron Rivers in Oklahoma, and Bear Butte, in South Dakota.Bear Butte, the South Dakota mountain sacred to the Cheyenne, photograph by Jon Sailer, 2022. Source: UnsplashBear Butte is a sacred mountain to the Cheyenne, who call it Nhkhe-vose, translating to Bear Hill, or Noah-vose, Giving Hill. According to Cheyenne belief, it is at Bear Butte that the Great Spirit, Maheoo, transmitted essential knowledge to Motseeve, the prophet commonly known as Sweet Medicine or Sweet Medicine Standing. This knowledge became the heart of Cheyenne society and culture, shaping them into feared mounted horse-riding warriors organized in distinct warrior societies on the Plains.By the early 1800s, the Cheyenne society was organized into two related tribes, the Suhtai (Staeoo), also known as Sutaio (Stataneoo), and the Tstshsthese / Tsitsistas (or Cheyenne). By the mid-19th century, the Suhtai merged with the Tstshsthese / Tsitsistas to form the Cheyenne as we know them today, although the two groups continue to have their own prophets. In 1825, the Cheyenne split into the Northern and Southern Cheyenne, with the Northern Cheyenne moving into present-day eastern Wyoming.By the 1820s, the Cheyennes hunting territory stretched from southern Montana through Wyoming (pictured here), photograph by Michael Kirsh, 2022. Source: UnsplashThe Northern Cheyenne fought at Little Bighorn alongside their historic allies, the Arapaho, under the command of respected chief Morning Star (Vhhve in the language of the Cheyenne), who was also one of the signatories of the first Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1851. As far as the Cheyenne and Arapaho are concerned, the treaty established that the lands between the Arkansas and North Platte Rivers, encompassing Wyoming and Nebraska south of the North Platte River, western Kansas, and Colorado north of Arkansas, were theirs to live on, without fearing the encroachment of American settlers.Buffalo Calf Road Woman and her husband, Black Coyote, were both skilled Northern Cheyenne warriors who fought together at the Battle of Little Bighorn. Just nine days before the battle, Buffalo Calf Road Woman had saved her wounded brother, Chief Comes in Sight, during the Battle of the Rosebud. The Cheyenne refer to this battle as The Battle Where the Girl Saved Her Brother.Cheyenne family, ca. 1871-1907. Source: Wikimedia CommonsThe Sioux claim that it was their warrior Moving Robe Woman who fatally stabbed Custer. In June 2005, storytellers of the Northern Cheyenne Tribe of Montana finally shared stories about the battle, stories that had been handed down for years from generation to generation, breaking the 100-year-long silence their ancestors had imposed for fear of retribution. Among the stories shared in their account, one concerns Buffalo Calf Road Woman. According to Cheyennes oral tradition, she was the one who knocked Custer off his horse with a club-like object before other warriors finished him off.The only known picture of her was taken between 1870 and 1875. It shows Buffalo Calf Road Woman staring straight into the camera with her braided hair falling in two thick braids across her chest.Minnie Hollow Wood and One Who Walks With the StarsNative American warrior on a charging horse clubbing a gun-brandishing soldier wearing his blue army uniform with a tomahawk weapon, 1890. Source: Brooklyn MuseumAt least two Lakota women warriors fought at Little Bighorn. One of them was Minnie Hollow Wood. The other was One Who Walks With the Stars, also known as Woman-Who-Walks-with-the-Stars.The Lakota, also known as Teton Sioux, are one of the three divisions of the Sioux, along with the Wihyena (or Western Dakota) and the Santee Lakota (or Eastern Dakota). They are divided into seven sub-tribes: the Sihu (commonly known as the Brul), the Oglla, Hkpapa (Hunkpapa), Miniconjou, Sihsapa (Blackfeet), Itzipho (Sans Arc), and Ohenupa (or Two Kettles). Crazy Horse, for instance, who fought in various battles against American settlers and soldiers before he died in 1877, was a member of the Oglla and Miniconjou sub-tribes.Lakota womans leggings, ca. 1870-1895. Source: Brooklyn MuseumOne Who Walks With the Stars was a member of the Oglla tribe. Her husband, Crow Dog (Ka ka), was a Brul Lakota warrior and subchief born in Horse Stealing Creek, in what is now Montana. Unsurprisingly, although Crow Dog did not kill anyone during the Battle of Little Bighorn, historians have been able to gather more information about him than about One Who Walks With the Stars. For a long time, she has been known mainly as Crow Dogs wife rather than as a respected Lakota warrior and an active participant in the Battle of Little Bighorn.She reportedly slashed, clubbed, and eventually killed two soldiers who were attempting to swim across the Little Bighorn River as she was rounding up stray cavalry horses near her husbands Brul Lakota camp.A wounded (possibly Cheyenne) warrior lies on the ground, bleeding from his mouth, next to his wounded horse, whos bleeding from his nose, as five army men fire at them, 1890. Source: Brooklyn MuseumIn 1925, nearly 50 years after the Battle of Little Bighorn, Minnie Hollow Wood (1856-1930s) was photographed staring into the camera wearing her warbonnet. Standing next to her was (likely) her husband, Hollow Wood, a Cheyenne warrior who also fought at Little Bighorn. Among the Lakota, Minnie Hollow Wood was the only woman entitled to wear a war bonnet as a symbol of gratitude from her tribe for her role in the battle. Unfortunately, not much else is known about Minnie Hollow Woods contribution to the victory of her people at Little Bighorn.In the aftermath of the battle, she and her husband surrendered to Colonel Nelson A. Miles (1839- 1925) at Fort Keogh in Montana. They lived the rest of their lives in the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation, located in the North Western Great Plains in southeastern Montana. In Cheyenne, it is known as Tshstno and was formerly called the Tongue River Reservation, after the Tongue River that borders it to the east.Cheyenne warriors captured by Custers forces after the Battle of the Washita River, here held prisoners at Fort Dodge next to U.S. Army chief John O. Austin, 1868. Source: Wikimedia CommonsMinnie Hollow Wood frequently worked with ethnographer and amateur historian Thomas Bailey Marquis until her death in the 1930s. She provided unique insights into the Battle of the Little Bighorn and shared the Native American perspective with Marquis and his white audience.The Cheyenne, Sioux, Arapaho, and Lakota were the undisputed warriors of the Battle of Little Bighorn. The death of General G. A. Custer held symbolic significance beyond practical value. The man who had led so many aggressive attacks against Native American camps, the man responsible for the slaughter of innocent and unarmed women and children at the Washita River, was finally dead, killed by Native American warriors. Custers defeat sent shockwaves across American society and the US Army, underlining their miscalculation of Native American resistance, fighting skills, and tactics, and deeply embarrassing the government.Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument, photograph by Karen Matinez, 2020. Source: UnsplashThe Cheyenne, Sioux, Arapaho, and Lakota, like many other Indigenous people worldwide, won the battle but lost the war. However, historians, academics, and the general public are now at long last re-evaluating the bravery and strength of Native American men and women, warriors and civilians alike, before and after the Battle of Little Bighorn.

0 Σχόλια

0 Μοιράστηκε

194 Views