WWW.THECOLLECTOR.COM

The Difficult Legacy of the Spanish Inquisition in the Americas

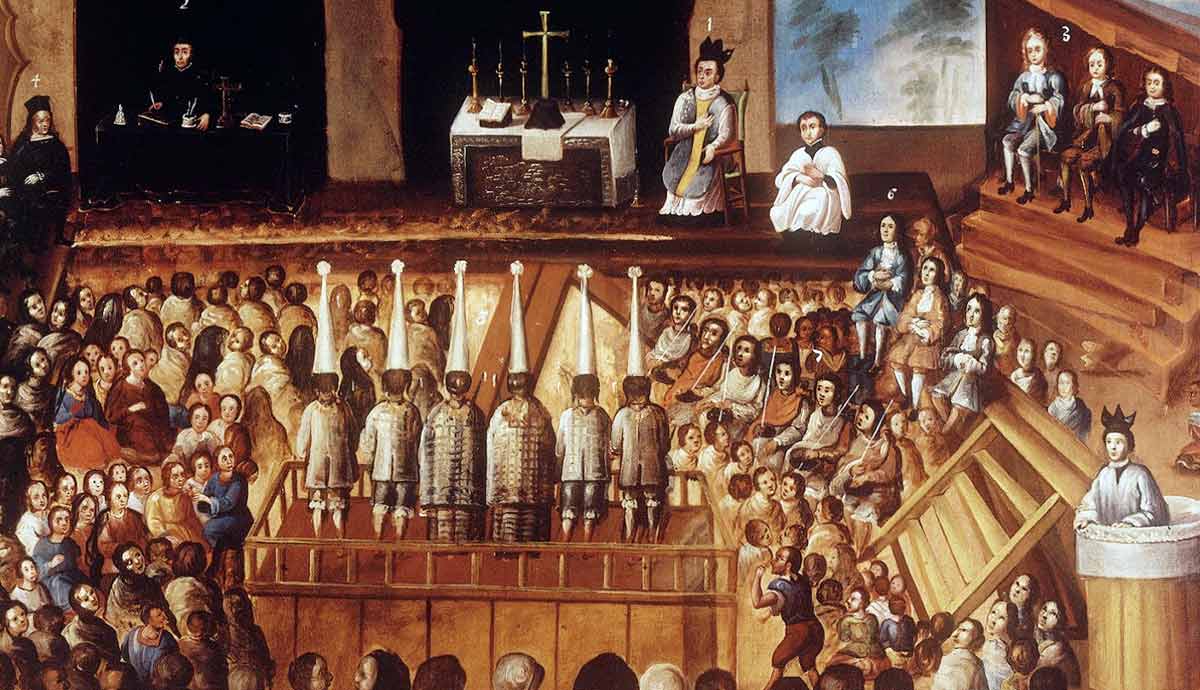

The Inquisition was not merely a mechanism of religious persecution but also a sophisticated instrument of ideological control that shaped culture, morality, and social structures in the colony. Examining cases such as the persecution of Jews and witch hunts reveals the brutality of its methods, its capacity to dismantle communities, the prejudices of the time, and how it perpetuated a legacy of fear and repression.The Inquisition and Its Expansion to AmericaShield of the Holy Inquisition of Mexico, Anonymous, 17th century. Source: Mediateca INAHThe Inquisition was an institution created by the Catholic Church in the 13th century to combat heresy and preserve orthodoxy. However, the Spanish Inquisition functioned somewhat differently from others. In the period of Catholic monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella, it was said that there were many Christians who, after being converted from Judaism, continued practicing their old customs. At the request of the Spanish rulers, Pope Sixtus IV issued a bull in 1478 in which he authorized them to appoint their own inquisitors and remove such heretics in perpetuity. The Spanish Inquisition became part of the State itself and answered to the policies and interests of the kingdom, not to the Pope or the Catholic hierarchy. The Spanish Inquisition quickly became an instrument of power for the monarchy, used to pressure and influence the beliefs of its subjects.In the nascent American colonies, the situation was different for two reasons. First, the distance from the center of power, so remote, allowed a greater laxity in the practice of Catholicism, deviating from the orthodoxy that had to be maintained on the peninsula; this led to fears that the colonies would attract people who were fleeing from this control. Second, there was also the question of Indigenous peoples and their religious practices. Ultimately, ideological and religious struggles in the Americas were not only due to internal deviations within Catholicism but also the belief systems deeply rooted in Indigenous societies.Inquisition tribunals were created in the Americas, one in Lima and another in Mexico; later, in 1610, a third tribunal was added in Cartagena de Indias. Among them, they had jurisdiction over the entire territory of Spanish America, and the most relevant cases were brought to these courts.Judaism: The First Crime of the InquisitionManuscript of Luis de Carvajal describing the Ten Commandments, c. 1595. Source: SmartHistory.orgJudaism was seen as a grave sin; after the religious unification following the Reconquista and the expulsion of the Jews, Catholic orthodoxy was imposed in Spain and in the new colonies. It was feared that Jews would escape to the New World in order to continue secretly practicing the rites far from the control of the authorities. Recent DNA studies of Latin Americans reveal a Sephardic ancestry much broader than was originally believed, even greater than in countries such as Spain and Portugal, which indicates the likelihood that many more Jews traveled than was thought, although many practiced in secret.A notable case is that of the Jewish leader Luis de Carvajal, one of the most famous in the New World and the first Jewish author in the Americas, whose work has endured to the present day. Much is known about his Judaism: how he adopted the pseudonym Jose Lumbroso (Joseph the Enlightened), how he circumcised himself with an old pair of scissors, how he prayed, how he celebrated his holidays and fasts, and how he assumed leadership of his sizeable secret Jewish community, which had fled the Inquisition from Portugal and Spain to Mexico in the mid-sixteenth century. Carvajal was caught and arrested for secretly practicing Judaism and was subjected to torture. Carvajal ended up betraying more than a hundred people who secretly practiced Judaism, including the names of his sister and his mother.General Auto-da-F in Mexico, 1649, Anonymous. Source: Mediateca INAHHis confession helped to reveal the internal structure of the Jewish community in Mexico City, which triggered the infamous autos de fe of 1596 and 1601. These were public ceremonies organized by the inquisitorial authorities in which the defendants were denounced and punished. The punishments ranged from public penances, confiscation of goods, forced labor, and, in the most severe cases, the relaxation to the secular arm, which meant being handed over to the civil authorities to be executed, generally by means of a stake. In these two autos de fe, two hundred and ten individuals were accused of various heresies, 86 of them Jews, of whom Carvajal had named 57. In total, 11 were burned at the stake, 10 of whom had been named by Carvajal. The eleventh was Carvajal himself.This process demonstrates the meticulous efficiency of the inquisitorial apparatus: extensive investigations and information networks, the detailed record of all interrogations and torture sessions. The Inquisition used torture to extract information, although most of the time, it was already known through other sources; it served to expand and confirm this information but also as a tool of terror and social control. Thus, it came to have the capacity to dismantle entire communities, destroying the cultural and social life of Jews in the viceroyalty. The autos de fe were ritualized and theatrical, since the objective was not only to punish the guilty but also to serve as a warning to reinforce Catholic orthodoxy and to display the power of the church.Hunting Witches: Superstition and ControlAuto da fe in the Town of San Bartolom Otzolotepec, Anonymous, 18th century. Source: Google Arts and CultureIn Spanish America, there existed an ancient magical tradition deeply connected to religious beliefs and medicinal practices. With the arrival of the Spaniards, a very rigid, dogmatic, and Eurocentric approach was imposed in which the ancient Indigenous idols were associated with representations of the devil. Furthermore, any Indigenous spiritual practice, even those exclusively related to natural medicine, was also demonized.Just as in the European tribunals, the high point of the persecution against superstitions and witches occurred in the first forty years of the 17th century, when the crypto-Jews were fewer in number, and the Lutherans no longer represented a significant threat. The Inquisition had to focus its efforts on other targets that would allow it to justify its existence and maintain ideological control.Accusations of witchcraft and superstition became an inexhaustible source of cases, particularly in the witchcraft epidemics imported from Europe, where fear reigned. These not only served to keep the prisons full but also silenced dissidents and maintained a social order aligned with colonial and ecclesiastical interests.Drawing in a file on heretical propositions, Jos Ventura Gonzlez, 1789-1790. Source: Memorica, Government of MexicoMany of the women accused of being witches or sorceresses belonged to lower social classes; they used these practices to pocket a few pesos, offering services related to love, wealth, and health. Some of them also engaged in prostitution, and witchcraft served as a tool to attract more clients or ensure their loyalty.A very well-known case was that of Paula de Eguluz, a Creole Black woman. In her file it is explained how, on a bad day, the devil appeared to her in the form of a woman and then as a very handsome man, with whom she had carnal relations and afterward went to a coven near Havana. She was sentenced to serve the poor in a hospital. This occurred in 1623, but in 1630, she again had to face the inquisitors, as she was once again accused of converting her neighbors and friends into witches. According to her statements, a little devil called Mantelillos had taught her the science of making strange cures and of exhuming corpses to devour them in her fantastic covens. This time, she was punished with two hundred lashes and was condemned to wear a habit and be imprisoned perpetually.This case shows a mixture of European conceptions of Satanism and the social and cultural dynamics proper to the colonial context. Many of the narrated elements, such as having relations with a demon or covens, did not necessarily reflect real experiences but rather were induced by the inquisitors in order to fit the confessions within the narratives imported from Europe.The Mulatta (The Supper at Emmaus) by Diego Gelzquez, circa 1618. Source: National Gallery of IrelandHistory also highlights Paulas vulnerable position, being a woman, Black, a slave, a healer, and having an active social life; she was more exposed to stigmatization and was made an easy target for accusations of witchcraft both by the authorities and by her own neighbors, who often denounced her and invented stories about her.Under inquisitorial pressures, Paula ended up confessing, either due to internalizing certain beliefs or, perhaps most likely, because it was a means of survival; confessing was a means to avoid more severe penalties. The reality was that sometimes there was no other way to save oneself; the inquisitors sought to fit the accounts within their pre-established notions of witchcraft.The sentences for this type of case were generally not severe and are in no way comparable with the great European tribunals burning all the witches who fell into their hands at the stake. The most common punishments were lashes, exile, serving in hospitals, or being interned with the sick.Behind many of these cases there was an underlying attempt to impose a morality, to punish sexuality and the women who defied hegemonic patriarchal narratives, ultimately seeking to exercise control over women, popular knowledge, and marginalized figures in a deeply unequal colonial system.Echoes of the InquisitionPainting depicting an auto-de-fe, Francisco Goya, 1808-1812. Source: Google Arts and CultureThe Inquisition was not only a system of religious persecution but also a sophisticated and meticulous system of justice that shaped the social and cultural life of the colony. Unlike the justice administered by ordinary courts, which was quite lax, the Inquisition was extremely careful in its procedures, with long trials and severe punishments. Although both types of courts belonged to the Spanish crown, the paramount importance of the Inquisition is visible; beyond punishment, it was a means of ideological control, shaping morality and imposing social rules.Fear was one of the most enduring legacies, for mentalities are the most difficult thing to change in history, enduring through material structures as well as economic and political changes. The surveillance, denunciation, and punishment of the Inquisition left a symbolic mark that persisted over time in subsequent censures, educational control, mechanisms of state repression, and control of information.However, the Inquisition also left an invaluable legacy of documentary sources, records that have allowed modern historians to understand the cultural aspects of everyday life and the experiences of women and ordinary people that were rarely documented elsewhere. Furthermore, because the accusations and trials focused on behaviors considered transgressive, they offer a view into the social practices, beliefs, and cultural tensions of the era. They must be seen as much more than simple norms, for they reveal a mechanism of control that sought to impose a uniform morality. The very prohibitions allow us to glimpse the behaviors that people practiced in secret.

0 Commentaires

0 Parts

202 Vue