0 Commentarii

0 Distribuiri

214 Views

Director

Elevate your Sngine platform to new levels with plugins from YubNub Digital Media!

-

Vă rugăm să vă autentificați pentru a vă dori, partaja și comenta!

-

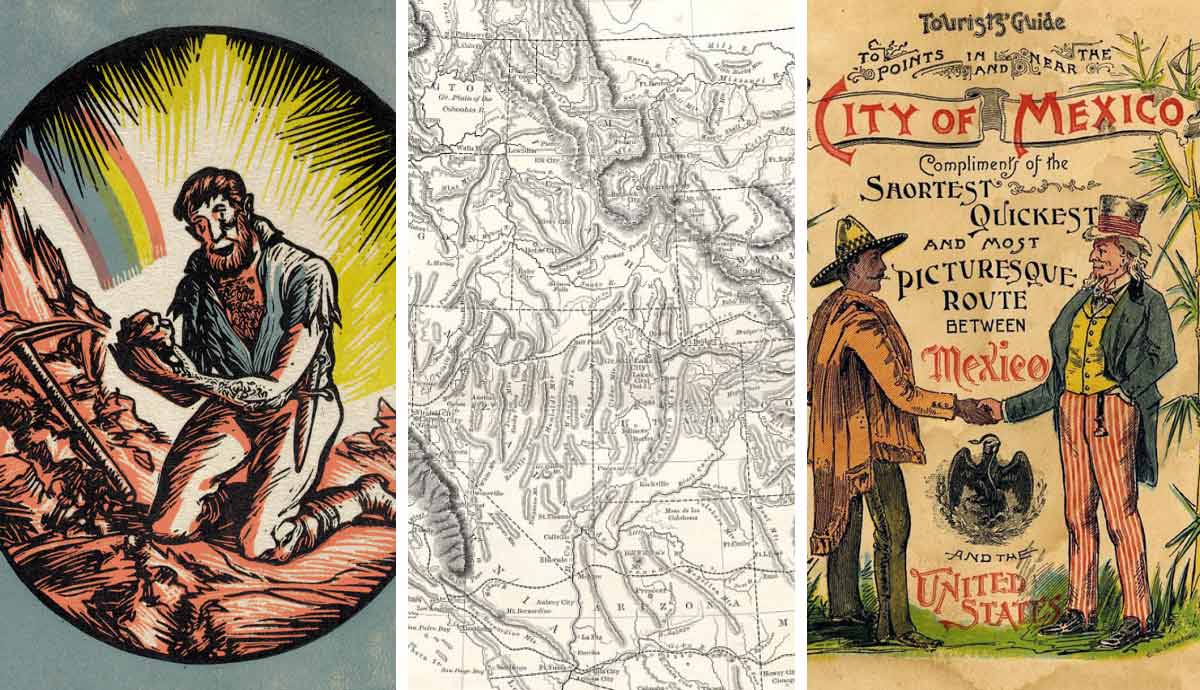

WWW.THECOLLECTOR.COMThe War That Made California American and Changed the WorldThe Mexican-American War is one of the shortest armed conflicts in the history of the United States. In addition to serving as the proving ground for talented US Army officers who fought on both sides of the American Civil War, the war resulted in huge territorial gains for the United States, elevating its international prestige and opening up economic opportunities over the following decades. However, Americas victory has been subject to negative interpretations in recent years due to its impact on local populations.Historical ContextPresident James K. Polk by John Sartain, 1845. Source: National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian InstitutionAlthough largely overlooked in modern society, the Mexican-American War was a significant event in American history. While the immediate causes of the conflict were the territorial disagreements following the annexation of the Republic of Texas in 1845, the Mexican-American War is indicative of several larger geopolitical, economic, and military trends of the United States in the early and mid-19th century.After winning independence in the American Revolutionary War, the United States sought to expand its territory westward. Guided by the defining pillar of Manifest Destiny, the idea that America had a divinely inspired mission to spread liberal values across its home continent, during the first half of the 19th century American statesmen such as Presidents Thomas Jefferson and James Monroe acquired new land via the Louisiana Purchase and Adams-Ons Treaty respectively. While these agreements saw the country incorporate territory from 15 current-day states to the south and west of the original 13 colonies, the United States also hoped to acquire Mexican territories including Texas, California, and New Mexico.By 1846, border disputes with Mexico over Texas southern boundary boiled over into armed hostilities. Shortly afterwards, President James K. Polk successfully prevailed upon Congress to declare war after an offer to purchase the desired territories was rejected out of hand by the Mexican authorities. The United States secured victory in several early engagements including the Battles of Palo Alto, Resaca de la Palma, and Monterrey as well as the Siege of Fort Texas.Final BattlesGeneral Winfield Scott, artist unknown, 1861. Source: National Museum of American History, Smithsonian InstitutionAfter intense fighting early in the conflict, the United States saw a path to final success by August 1847. At the Battle of Contreras, American forces under General Winfield Scott achieved decisive victory, opening the way to the Mexican capital. On the same day, August 20, 1847, Scotts soldiers effectively overcame Mexican defenses at Churubusco despite heavy resistance.Nearly three weeks later, Scotts army inched closer to Mexico City. On September 8, 1847, American forces defeated Mexican troops at the Battle of Molino del Rey after some of the bloodiest fighting of the Mexican-American War. Before reaching the capital, however, General Scott and his army, including then-lieutenant and future president Ulysses S. Grant, had to negotiate Mexican fortifications at Chapultepec Castle. The stronghold presented unique challenges for the American offensive, but to secure western avenues of approach to Mexico City, capturing the castle was vital.Through effective artillery bombardment and overwhelming infantry attacks, General Scott and his American troops successfully seized Chapultepec Castle from the outnumbered Mexican garrison. This victory allowed the swift capture of Mexico City after light civilian resistance and the departure of government officials, essentially ending major combat operations of the Mexican-American War on September 17, 1847. The Mexican government sued for peace and after five months the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was concluded between the two parties.Treaty of Guadalupe HidalgoMap of western states less than two decades after the Mexican-American War, 1865. Source: National Museum of American History, Smithsonian InstitutionAs the victors of the Mexican-American War, the United States was heavily favored in the terms of the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Most significantly, Mexico was obliged to surrender over 50 percent of its land mass to the United States. The ceded territory, composed of the modern-day states of Nevada, California, and Utah in addition to parts of Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and Wyoming, fulfilled many of the expansionistic desires of the United States that caused the conflict.A second outcome of the agreement led to Mexican recognition of the American annexation of Texas and defined its boundaries. While Texas successfully obtained its independence from Mexico over ten years earlier, many Mexicans refused to recognize its legitimacy. After the war, however, Mexico acknowledged Texas as part of the United States and recognized its southern border at the Rio Grande River. While these territorial gains significantly benefited the United States, the Americans did offer some financial compensation. Despite assuming $3.25 million in debt owed to United States citizens, Mexico was paid $15 million for its lost lands.With over half a million square miles in newly acquired land, America faced the elusive question of how to handle Mexican citizens living in the newly annexed regions. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo granted affected peoples the option of moving within the revised and narrowed Mexican borders or stay put as American citizens with full civil rights.Americas Victorious GeneralsGeneral Zachary Taylor illustrated by Marie Alexandre Alophe, 1849. Source: National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian InstitutionThe Mexican-American War had tangible outcomes on the conflicts victorious leaders. Militarily, General Zachary Taylor commanded US forces during the early stages of the war and gained victory at Palo Alto and Buena Vista. These conquests made Taylor a war hero and inspired him to run a successful campaign to become the countrys twelfth president. Nicknamed Old Rough and Ready, the popular general took office in 1849 but died less than two years into his term.General Winfield Scott succeeded Taylor as commander of the main US army and achieved the victories that ended the conflict. Scott remained a key military figure up to the American Civil War and was responsible for Union strategy during its earliest stage, but his retirement in 1861 passed the torch to subordinate officers who served alongside him in Texas and Mexico. The Mexican-American War provided comprehensive combat experience to young junior officers Generals Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee, who served as the principal commanders of the Union and Confederate Armies during the Civil War. Grants victories in the Civil War paved his way to serve two terms as the countrys 18th president.Politically, President Polks policies and decisions helped instigate the Mexican-American War. Polk did not seek reelection after the end of his first term and died from illness three months later in June 1849. Despite enjoying a rise in public approval in the years following the conflict, Polks legacy has diminished over time. While the United States economically thrived with new territorial additions, critics including future president Abraham Lincoln were outspoken in their opposition to Polk, arguing that war with Mexico was a conscious effort to expand slavery.Long-Term Outcomes of VictoryIllustration of gold in California by Harry Cimino, 1926. Source: Smithsonian American Art MuseumAs victors of the Mexican-American War, the United States benefitted long-term from the conflict. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo granted over 500,000 square miles of land to the United States, which were subsequently organized into seven states that have made significant contributions to the American economy.In the years following the hostilities, California, one of the primary targets of American expansion due to its long Pacific coastline, witnessed mass immigration as a result of the Gold Rush. Officially beginning in January 1848, just weeks before the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgos signing, the California Gold Rush saw over 300,000 miners move west seeking to make their fortunes. While the movement lasted less than a decade and most entrepreneurs failed to become rich, its effects are far-reaching. The Gold Rush led to a diverse population boom, initiating a process to make it the most populous state in America today and an economic powerhouse as the home of Silicon Valley.A final lasting outcome of the Mexican-American War is the strong and lasting Mexican presence in southwestern regions of the United States. When Mexican families were given the choice of remaining in newly acquired territories or relocating to Mexicos reduced boundaries following the war, many civilians chose to stay in the United States with full protections under the countrys laws. This greatly influenced the society, culture, and economics in the southwestern United States.Modern InterpretationsTourists guide from an advertised route between Mexico and the United States, 1890. Source: National Museum of American History, Smithsonian InstitutionDespite the major benefits enjoyed by the United States after the Mexican-American War, the conflict also leaves a controversial legacy in the present day. The expansion of American frontiers resulted in the displacement of Native American tribes from acquired regions, mirroring developments after the War of 1812 just three decades prior. The methods by which the United States gained and exploited its southwestern territories are often viewed critically in the 21st century.Aside from harmful consequences to Native American groups, the Mexican-American War also opened the door to influential debates over the future of slavery in the United States. While Democratic congressman David Wilmot presented the Wilmot Proviso before Congress to prevent slavery from expanding into the regions obtained by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, the proposal was rejected by Congress. Resulting disagreements surrounding slavery in both existing and newly acquired states contributed to the American Civil War just over a decade later. The 1850s saw the realignment of American party politics and the establishment of the Republican Party led by anti-slavery figures including President Abraham Lincoln.As a result, while the United States made considerable gains following victory in the Mexican-American War, many Americans believe the conflict was illegitimate and a cause of embarrassment for the countrys claims to be spreading freedom and democracy.0 Commentarii 0 Distribuiri 215 Views

WWW.THECOLLECTOR.COMThe War That Made California American and Changed the WorldThe Mexican-American War is one of the shortest armed conflicts in the history of the United States. In addition to serving as the proving ground for talented US Army officers who fought on both sides of the American Civil War, the war resulted in huge territorial gains for the United States, elevating its international prestige and opening up economic opportunities over the following decades. However, Americas victory has been subject to negative interpretations in recent years due to its impact on local populations.Historical ContextPresident James K. Polk by John Sartain, 1845. Source: National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian InstitutionAlthough largely overlooked in modern society, the Mexican-American War was a significant event in American history. While the immediate causes of the conflict were the territorial disagreements following the annexation of the Republic of Texas in 1845, the Mexican-American War is indicative of several larger geopolitical, economic, and military trends of the United States in the early and mid-19th century.After winning independence in the American Revolutionary War, the United States sought to expand its territory westward. Guided by the defining pillar of Manifest Destiny, the idea that America had a divinely inspired mission to spread liberal values across its home continent, during the first half of the 19th century American statesmen such as Presidents Thomas Jefferson and James Monroe acquired new land via the Louisiana Purchase and Adams-Ons Treaty respectively. While these agreements saw the country incorporate territory from 15 current-day states to the south and west of the original 13 colonies, the United States also hoped to acquire Mexican territories including Texas, California, and New Mexico.By 1846, border disputes with Mexico over Texas southern boundary boiled over into armed hostilities. Shortly afterwards, President James K. Polk successfully prevailed upon Congress to declare war after an offer to purchase the desired territories was rejected out of hand by the Mexican authorities. The United States secured victory in several early engagements including the Battles of Palo Alto, Resaca de la Palma, and Monterrey as well as the Siege of Fort Texas.Final BattlesGeneral Winfield Scott, artist unknown, 1861. Source: National Museum of American History, Smithsonian InstitutionAfter intense fighting early in the conflict, the United States saw a path to final success by August 1847. At the Battle of Contreras, American forces under General Winfield Scott achieved decisive victory, opening the way to the Mexican capital. On the same day, August 20, 1847, Scotts soldiers effectively overcame Mexican defenses at Churubusco despite heavy resistance.Nearly three weeks later, Scotts army inched closer to Mexico City. On September 8, 1847, American forces defeated Mexican troops at the Battle of Molino del Rey after some of the bloodiest fighting of the Mexican-American War. Before reaching the capital, however, General Scott and his army, including then-lieutenant and future president Ulysses S. Grant, had to negotiate Mexican fortifications at Chapultepec Castle. The stronghold presented unique challenges for the American offensive, but to secure western avenues of approach to Mexico City, capturing the castle was vital.Through effective artillery bombardment and overwhelming infantry attacks, General Scott and his American troops successfully seized Chapultepec Castle from the outnumbered Mexican garrison. This victory allowed the swift capture of Mexico City after light civilian resistance and the departure of government officials, essentially ending major combat operations of the Mexican-American War on September 17, 1847. The Mexican government sued for peace and after five months the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was concluded between the two parties.Treaty of Guadalupe HidalgoMap of western states less than two decades after the Mexican-American War, 1865. Source: National Museum of American History, Smithsonian InstitutionAs the victors of the Mexican-American War, the United States was heavily favored in the terms of the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Most significantly, Mexico was obliged to surrender over 50 percent of its land mass to the United States. The ceded territory, composed of the modern-day states of Nevada, California, and Utah in addition to parts of Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and Wyoming, fulfilled many of the expansionistic desires of the United States that caused the conflict.A second outcome of the agreement led to Mexican recognition of the American annexation of Texas and defined its boundaries. While Texas successfully obtained its independence from Mexico over ten years earlier, many Mexicans refused to recognize its legitimacy. After the war, however, Mexico acknowledged Texas as part of the United States and recognized its southern border at the Rio Grande River. While these territorial gains significantly benefited the United States, the Americans did offer some financial compensation. Despite assuming $3.25 million in debt owed to United States citizens, Mexico was paid $15 million for its lost lands.With over half a million square miles in newly acquired land, America faced the elusive question of how to handle Mexican citizens living in the newly annexed regions. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo granted affected peoples the option of moving within the revised and narrowed Mexican borders or stay put as American citizens with full civil rights.Americas Victorious GeneralsGeneral Zachary Taylor illustrated by Marie Alexandre Alophe, 1849. Source: National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian InstitutionThe Mexican-American War had tangible outcomes on the conflicts victorious leaders. Militarily, General Zachary Taylor commanded US forces during the early stages of the war and gained victory at Palo Alto and Buena Vista. These conquests made Taylor a war hero and inspired him to run a successful campaign to become the countrys twelfth president. Nicknamed Old Rough and Ready, the popular general took office in 1849 but died less than two years into his term.General Winfield Scott succeeded Taylor as commander of the main US army and achieved the victories that ended the conflict. Scott remained a key military figure up to the American Civil War and was responsible for Union strategy during its earliest stage, but his retirement in 1861 passed the torch to subordinate officers who served alongside him in Texas and Mexico. The Mexican-American War provided comprehensive combat experience to young junior officers Generals Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee, who served as the principal commanders of the Union and Confederate Armies during the Civil War. Grants victories in the Civil War paved his way to serve two terms as the countrys 18th president.Politically, President Polks policies and decisions helped instigate the Mexican-American War. Polk did not seek reelection after the end of his first term and died from illness three months later in June 1849. Despite enjoying a rise in public approval in the years following the conflict, Polks legacy has diminished over time. While the United States economically thrived with new territorial additions, critics including future president Abraham Lincoln were outspoken in their opposition to Polk, arguing that war with Mexico was a conscious effort to expand slavery.Long-Term Outcomes of VictoryIllustration of gold in California by Harry Cimino, 1926. Source: Smithsonian American Art MuseumAs victors of the Mexican-American War, the United States benefitted long-term from the conflict. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo granted over 500,000 square miles of land to the United States, which were subsequently organized into seven states that have made significant contributions to the American economy.In the years following the hostilities, California, one of the primary targets of American expansion due to its long Pacific coastline, witnessed mass immigration as a result of the Gold Rush. Officially beginning in January 1848, just weeks before the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgos signing, the California Gold Rush saw over 300,000 miners move west seeking to make their fortunes. While the movement lasted less than a decade and most entrepreneurs failed to become rich, its effects are far-reaching. The Gold Rush led to a diverse population boom, initiating a process to make it the most populous state in America today and an economic powerhouse as the home of Silicon Valley.A final lasting outcome of the Mexican-American War is the strong and lasting Mexican presence in southwestern regions of the United States. When Mexican families were given the choice of remaining in newly acquired territories or relocating to Mexicos reduced boundaries following the war, many civilians chose to stay in the United States with full protections under the countrys laws. This greatly influenced the society, culture, and economics in the southwestern United States.Modern InterpretationsTourists guide from an advertised route between Mexico and the United States, 1890. Source: National Museum of American History, Smithsonian InstitutionDespite the major benefits enjoyed by the United States after the Mexican-American War, the conflict also leaves a controversial legacy in the present day. The expansion of American frontiers resulted in the displacement of Native American tribes from acquired regions, mirroring developments after the War of 1812 just three decades prior. The methods by which the United States gained and exploited its southwestern territories are often viewed critically in the 21st century.Aside from harmful consequences to Native American groups, the Mexican-American War also opened the door to influential debates over the future of slavery in the United States. While Democratic congressman David Wilmot presented the Wilmot Proviso before Congress to prevent slavery from expanding into the regions obtained by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, the proposal was rejected by Congress. Resulting disagreements surrounding slavery in both existing and newly acquired states contributed to the American Civil War just over a decade later. The 1850s saw the realignment of American party politics and the establishment of the Republican Party led by anti-slavery figures including President Abraham Lincoln.As a result, while the United States made considerable gains following victory in the Mexican-American War, many Americans believe the conflict was illegitimate and a cause of embarrassment for the countrys claims to be spreading freedom and democracy.0 Commentarii 0 Distribuiri 215 Views -

WWW.THECOLLECTOR.COMHow Underwater Shells Became the First Global MoneyThere are over 250 different species of cowrie shells around the globe. However, two species in particular became woven into various Asian and African societies both as a form of currency and an object with ceremonial, cultural, and ritualistic significance. From the 17th century, cowries, gold, and tobacco became entwined in the Atlantic, playing an integral role in the Transatlantic Slave Trade. In North America, cowries even found a place within the 17th and 18th century fur trade. From the beaches of the Maldives, cowries transformed into a cornerstone of the modern world.Monetaria Moneta: The Money CowrieCowrie money and Euro cent coins. Source: Wikimedia CommonsCowries can be found in the waters of Central Mexico, coastal East Africa, and areas of South and Southeast Asia. However, one species of cowrie in particular gained significance as a form of currency to the extent its Latin name, monetaria moneta, literally translates to money cowrie. It is found only in the Maldives, an archipelago (island group) off the coast of present-day Sri Lanka. It is here that the cowrie snail plays a role in the underwater ecosystem, eating algae to maintain the health of surrounding coral reefs and other habitats.Above water, however, cowries came to be valued for their visual appearance. Their milky-smooth surfaces have been likened to porcelain and vice versa. In fact, the word porcelain comes from the word porcellanaduring Marco Polos travels to China in the 13th century, he came across cowrie shells in various parts of Asia, particularly in trade settings. To him, the rounded backs of the shells bore similarities to a porcellus, or piglet. It is no wonder that Marco Polo saw similarities between porcelain and cowrie shells, as both had a polished glow and snow white surfaces.Extracting the CowrieTiger cowrie (Cypraea tigris). The snail can stretch its body around the shell, as depicted here. Source: FlickrAccording to various Arab, Portuguese, British, and Dutch sources, cowries were extracted using several methods. Cowries washed up on shore were considered low quality. This was due to surface weathering after being continuously rolled on the beach, causing them to lose their shine and luster. The small animal inside needed to be living in order for cowrie shells to be of any value. Cowries were also mainly found in the atolls, or islands surrounded by coral reefs, of Ari, Huvadhu, and Haddhunmathi.Although several methods of cowrie extraction have been recorded, the one used most frequently was the wading method. This involved going into sea at about hip-level and pulling cowries off stones beneath the shallow surface. With this method, around 12,000 could be gathered by a single person in a day. Notably, this labor would be done primarily by Maldivian women. However, this changed in the 19th century to include men, most likely due to high demand.Photograph of the North Mal Atoll, Maldives. Source: rawpixel.com10th century Muslim traveler and historian al-Masudi records that from the sea, shells would be placed on shore, where the unfortunate inhabitants of these shells would be dried out under the heat of the sun. Four centuries later, however, one of the most famous Muslim travellers, Ibn Battuta, records that shells would be buried underground in pits instead. After an intensive cleaning process with both sea and freshwater, they would be wrapped into bundles made from coconut leaves called kotta, which numbered 12,000 shells.Whichever method was used, the result was the sameonce the animal was dried out, the shell transformed from a part of the Maldivian biological ecosystem into a commodity ready to be exchanged between merchants operating in the Indian Ocean trade network.Ancient CowriesLeather container covered entirely with cowrie shells, Niger. Source: Science Museum Group, LondonCowries have been found at archaeological sites associated with the Shang Dynasty in China (1600-1046 BCE), the Indus Valley Civilization (3300-1300 BCE), and the Mauryan Empire (322-185 BCE). The 1250 BCE tomb of Lady Hao (or Fu Hao), the favorite wife of Shang emperor Wu Ding, revealed over 6,800 cowries alongside jade, various metals, and other important objects. The cowries were definitely imports, and their presence within such a sacred space as an elite burial speaks to the high value ancient Chinese society placed on cowries.This also seeped into currencydue to the distance between China and the Maldives, cowries were not easily incorporated into the monetary system. Yet, they did not abandon the idea of cowries as money completely. Although the role of cowries within as currency in ancient China is much debated, cowrie-shaped objects were carved from materials such as stone, jade, metal, and bone. However, by the end of the Han Dynasty, these faux cowries would become replaced entirely by metal money in the form of coins.Cowries as Currency: Bengal and ThailandFrench cartographer Jacques-Nicolas Bellins map of the Bay of Bengal, circa 1747. Source: Wikimedia CommonsAfter being plucked out of Maldivian beaches, cowries would await export. Notably, cowries were not used as a form of currency within the Maldives itself, which used silver coins. The Bay of Bengal was one of the main export regions for cowries. This could have been due to the abundance of rice in this region, a diet staple of Maldivians. 14th century Chinese traveller Wang Dayuan even noted that one shipload of cowries would be sent in exchange for a shipload of rice.Through this exchange, the Bay of Bengal gained a steady influx of cowrie shells. By the 7th century CE, these were incorporated into their monetary system, alongside gold, silver, and also pearls. Over time, cowries began to be used for small transactions, followed by silver, then gold for larger transactions. In the Bay of Bengals Odisha province, Wang Dayuan recorded that 250 cowries could be exchanged for one basket of rice.Wat Chaiwatthanaram in Ayutthaya Historical Park in Ban Pom, Thailand. Source: pexels.comBengal also became an exporter of cowries to regions in the east, specifically on the monsoon trade routes to Southeast Asia. In present-day Thailand, cowrie shells were used as a form of currency. The Mangrayathammasart, a 13th century legal code promulgated by King Mangrai of Chiang Mai in present-day north Thailand, listed cowries as a form of payment for fines, alongside silver coins. Cowries would also be used for purchasing clothes, animals, tools, enslaved people, and even land. Cowrie shells were even used to incentivize soldiers. Allegedly, King Mangrai would provide soldiers with cowries and silver before battle, enticing members of Chiang Mai society to serve in his army (Baker and Phongpaichit, p. 98). Cowries were later used by the Kingdom of Ayutthaya in central Thailand, a major node in the Indian Ocean trade.Cowries, Culture, and Currency: Pre-1500s West AfricaBarjees (also Barjis) is a board game, possibly of Persian origin, where cowries are thrown onto an embroidered cloth board. Source: Wikimedia CommonsIn an age of paper money, metal coins, and cards as common means of exchange, the concept of shells as currency may sound inefficient. However, cowrie shells were impossible to forge, were not easily broken, could not be melted down into something else, and were always of a similar size, shape, and weight. Besides currency, they could be easily incorporated into any ritual, ceremonial, or everyday object. This was especially the case in many regions throughout East, Central, and West Africa.The eastern coast of Africa, specifically from southern Somalia to Mozambique, is often referred to as the Swahili coast due to the presence of a unified Swahili culture. The Swahili coast was home to its own species of cowrie, the monetaria annulus, which were mainly from the Zanzibar archipelago off the coast of present-day Tanzania. Although cowries also circulated in West Africa, these were typically from the Maldives, and arrived in West Africa after a one-year journey through the trans-Saharan trade network.Maldivian cowries were present in West Africa at least by the 7th century CE. They were used as adornments in certain communities in the form of jewelry, headpieces, and as decorations tied into womens hair. A 7th century burial at the site of Kissi (present-day Burkina Faso) revealed several cowries drilled with holes, strung together and placed in the location of the head, possibly a woman, as a form of a headpiece.Cowries were also embedded with meaning exceeding the bounds of decorationthey were incorporated into rituals, ceremonies, objects, and became affiliated with symbols of fertility and protection. They also functioned as objects whose ownership demonstrated power and status. Further, at least by the 14th century, cowries were being used as currency in places like Gao (an inland city in present-day Mali).Sine Qua Non: Cowries as the Absolute ConditionA photograph of cowrie shells taken in Kolkata, West Bengal, India. Source: Wikimedia CommonsThe longstanding history of cowries in West Africa was noted by the Portuguese in the 16th century, who understood that the societies they encountered on the West African coast, especially in the Bight of Benin (including present-day Nigeria, Ghana, Benin, and Togo), highly valued these objects and used them as a tool of monetary exchange. The Portuguese brought the first European shipment of cowries from the Maldives to the Bight of Benin in 1515. By 1690, cowries were an instrumental unit of exchange for European merchants to buy enslaved West Africans bound for the Americas.Although cowrie shells were used in West Africa prior to European arrival, following the establishment of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, cowries filtered into West Africa in unprecedented numbers. In the late 17th century, cowries were 20-50 percent of the purchasing price of a person (Heath, p. 61). This was 10-30,000 shells. By 1770, it rose to 160-176,000 shells. Cowries became the sine qua non, the absolute condition, to carry out trade with coastal West African leaders (Hogendorn, p. 32).1899 Map of the Slave Trade of Africa by Harry Hamilton Johnston and John George Bartholomew. Source: New York Public LibraryCowries werent the only currency of the slave trade (Heath, p. 61). Other objects, consumables, and materials desired by West Africans leading the slave trade were also incorporated into trade transactions. Many of these objects came from European colonies throughout the Americas and Caribbean, and were often produced by enslaved West African laborthese were items such as sugar, alcohol, gold, and tobacco processed with molasses from Bahia (present-day Brazil). Gold dust would usually remain in the hands of Dahomean kings, while cowries would circulate in local markets and all strata of West African society.Counting the CowrieString of cowrie Shells from Ancient Egyptian Hepy Burial, ca. 1950-1885 BCE. Source: Metropolitan Museum of ArtBetween 1700 and 1790, 10 billion cowrie shells were shipped from British and Dutch ports, like London and Amsterdam, to West Africa. A 1780 settlement between the Yoruba Empire and Dahomey Kingdom was made in 400 bags of cowries, the equivalent of 1,600 at the time. Today, this is the same purchasing power as approximately 247,540. However, how would this amount of cowries be accounted for and organized in transactions?Once in West Africa, cowries would often be drilled with holes and placed on string in units of 40. A similar method of drilling and stringing cowries would also appear in East Africa. In the Buganda Kingdom of present-day Uganda, East African cowries were put on strings of 100, but could be halved or even broken down to units of five per string. In doing so, they could be used for transactions of varying value. Even in the above photo of a Shang Dynasty cowrie carved from bone, a visible hole was drilled in the back. This could suggest a similar way of keeping cowries organized, as far back as 1200 BCE or even earlier.North American CowriesWampam Shoulder Belt for a Powder Horn, 19th century. Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New YorkCowries even travelled as far as North America, where they were also used as currency in the fur trade between European settlers and merchants with various indigenous groups. Cowries were present at several indigenous burials in Queens, New York and Long Island. It is possible they were brought to North America by both the Dutch and French. Trading in a natural currency like shells would not have been foreign to European settlerstransactions already taking place between themselves and various Cherokee, Algonquian, and Iroquois Confederacy peoples who used wampam as a currency, which were tiny shell beads. Burials of the Arikara in South Dakota have also revealed over 44 cowries of the Maldivian monetaria moneta species, indicative of the spread of the trade in cowries.From the Maldives to the WorldA Ghanaian one-cent cedi, issued in 1979. Source: Wikimedia CommonsCowries from the Maldives appear all across the globe. They are present in regions as far as China in the east, and North America in the west, not to mention all the cultures and regions in between. Cowries were, and still are, a commodity that connected many regions and cultures throughout both time and space. They were the currency for transactional exchange for anything from objects to people. Both an economic tool and a cultural object, their significance remains today, albeit in more opaque ways. In West Africa, although cowries are no longer used as currency, the Ghanaian one cedi coin bears an image of a cowrie.SourcesBaker, C., & Phongpaichit, P. (2017). A History of Ayutthaya: Siam in the Early Modern World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Heath Barbara (2016). Commoditization, Consumption and Interpretive Complexity: The Contingent Role of Cowries in the Early Modern World. Presented at Society for Historical Archaeology, Washington, D.C.Hogendorn, J. S. (1981). A supplyside aspect of the African slave trade: The cowrie production and exports of the Maldives. Slavery & Abolition, 2 (1), 3152.0 Commentarii 0 Distribuiri 214 Views

WWW.THECOLLECTOR.COMHow Underwater Shells Became the First Global MoneyThere are over 250 different species of cowrie shells around the globe. However, two species in particular became woven into various Asian and African societies both as a form of currency and an object with ceremonial, cultural, and ritualistic significance. From the 17th century, cowries, gold, and tobacco became entwined in the Atlantic, playing an integral role in the Transatlantic Slave Trade. In North America, cowries even found a place within the 17th and 18th century fur trade. From the beaches of the Maldives, cowries transformed into a cornerstone of the modern world.Monetaria Moneta: The Money CowrieCowrie money and Euro cent coins. Source: Wikimedia CommonsCowries can be found in the waters of Central Mexico, coastal East Africa, and areas of South and Southeast Asia. However, one species of cowrie in particular gained significance as a form of currency to the extent its Latin name, monetaria moneta, literally translates to money cowrie. It is found only in the Maldives, an archipelago (island group) off the coast of present-day Sri Lanka. It is here that the cowrie snail plays a role in the underwater ecosystem, eating algae to maintain the health of surrounding coral reefs and other habitats.Above water, however, cowries came to be valued for their visual appearance. Their milky-smooth surfaces have been likened to porcelain and vice versa. In fact, the word porcelain comes from the word porcellanaduring Marco Polos travels to China in the 13th century, he came across cowrie shells in various parts of Asia, particularly in trade settings. To him, the rounded backs of the shells bore similarities to a porcellus, or piglet. It is no wonder that Marco Polo saw similarities between porcelain and cowrie shells, as both had a polished glow and snow white surfaces.Extracting the CowrieTiger cowrie (Cypraea tigris). The snail can stretch its body around the shell, as depicted here. Source: FlickrAccording to various Arab, Portuguese, British, and Dutch sources, cowries were extracted using several methods. Cowries washed up on shore were considered low quality. This was due to surface weathering after being continuously rolled on the beach, causing them to lose their shine and luster. The small animal inside needed to be living in order for cowrie shells to be of any value. Cowries were also mainly found in the atolls, or islands surrounded by coral reefs, of Ari, Huvadhu, and Haddhunmathi.Although several methods of cowrie extraction have been recorded, the one used most frequently was the wading method. This involved going into sea at about hip-level and pulling cowries off stones beneath the shallow surface. With this method, around 12,000 could be gathered by a single person in a day. Notably, this labor would be done primarily by Maldivian women. However, this changed in the 19th century to include men, most likely due to high demand.Photograph of the North Mal Atoll, Maldives. Source: rawpixel.com10th century Muslim traveler and historian al-Masudi records that from the sea, shells would be placed on shore, where the unfortunate inhabitants of these shells would be dried out under the heat of the sun. Four centuries later, however, one of the most famous Muslim travellers, Ibn Battuta, records that shells would be buried underground in pits instead. After an intensive cleaning process with both sea and freshwater, they would be wrapped into bundles made from coconut leaves called kotta, which numbered 12,000 shells.Whichever method was used, the result was the sameonce the animal was dried out, the shell transformed from a part of the Maldivian biological ecosystem into a commodity ready to be exchanged between merchants operating in the Indian Ocean trade network.Ancient CowriesLeather container covered entirely with cowrie shells, Niger. Source: Science Museum Group, LondonCowries have been found at archaeological sites associated with the Shang Dynasty in China (1600-1046 BCE), the Indus Valley Civilization (3300-1300 BCE), and the Mauryan Empire (322-185 BCE). The 1250 BCE tomb of Lady Hao (or Fu Hao), the favorite wife of Shang emperor Wu Ding, revealed over 6,800 cowries alongside jade, various metals, and other important objects. The cowries were definitely imports, and their presence within such a sacred space as an elite burial speaks to the high value ancient Chinese society placed on cowries.This also seeped into currencydue to the distance between China and the Maldives, cowries were not easily incorporated into the monetary system. Yet, they did not abandon the idea of cowries as money completely. Although the role of cowries within as currency in ancient China is much debated, cowrie-shaped objects were carved from materials such as stone, jade, metal, and bone. However, by the end of the Han Dynasty, these faux cowries would become replaced entirely by metal money in the form of coins.Cowries as Currency: Bengal and ThailandFrench cartographer Jacques-Nicolas Bellins map of the Bay of Bengal, circa 1747. Source: Wikimedia CommonsAfter being plucked out of Maldivian beaches, cowries would await export. Notably, cowries were not used as a form of currency within the Maldives itself, which used silver coins. The Bay of Bengal was one of the main export regions for cowries. This could have been due to the abundance of rice in this region, a diet staple of Maldivians. 14th century Chinese traveller Wang Dayuan even noted that one shipload of cowries would be sent in exchange for a shipload of rice.Through this exchange, the Bay of Bengal gained a steady influx of cowrie shells. By the 7th century CE, these were incorporated into their monetary system, alongside gold, silver, and also pearls. Over time, cowries began to be used for small transactions, followed by silver, then gold for larger transactions. In the Bay of Bengals Odisha province, Wang Dayuan recorded that 250 cowries could be exchanged for one basket of rice.Wat Chaiwatthanaram in Ayutthaya Historical Park in Ban Pom, Thailand. Source: pexels.comBengal also became an exporter of cowries to regions in the east, specifically on the monsoon trade routes to Southeast Asia. In present-day Thailand, cowrie shells were used as a form of currency. The Mangrayathammasart, a 13th century legal code promulgated by King Mangrai of Chiang Mai in present-day north Thailand, listed cowries as a form of payment for fines, alongside silver coins. Cowries would also be used for purchasing clothes, animals, tools, enslaved people, and even land. Cowrie shells were even used to incentivize soldiers. Allegedly, King Mangrai would provide soldiers with cowries and silver before battle, enticing members of Chiang Mai society to serve in his army (Baker and Phongpaichit, p. 98). Cowries were later used by the Kingdom of Ayutthaya in central Thailand, a major node in the Indian Ocean trade.Cowries, Culture, and Currency: Pre-1500s West AfricaBarjees (also Barjis) is a board game, possibly of Persian origin, where cowries are thrown onto an embroidered cloth board. Source: Wikimedia CommonsIn an age of paper money, metal coins, and cards as common means of exchange, the concept of shells as currency may sound inefficient. However, cowrie shells were impossible to forge, were not easily broken, could not be melted down into something else, and were always of a similar size, shape, and weight. Besides currency, they could be easily incorporated into any ritual, ceremonial, or everyday object. This was especially the case in many regions throughout East, Central, and West Africa.The eastern coast of Africa, specifically from southern Somalia to Mozambique, is often referred to as the Swahili coast due to the presence of a unified Swahili culture. The Swahili coast was home to its own species of cowrie, the monetaria annulus, which were mainly from the Zanzibar archipelago off the coast of present-day Tanzania. Although cowries also circulated in West Africa, these were typically from the Maldives, and arrived in West Africa after a one-year journey through the trans-Saharan trade network.Maldivian cowries were present in West Africa at least by the 7th century CE. They were used as adornments in certain communities in the form of jewelry, headpieces, and as decorations tied into womens hair. A 7th century burial at the site of Kissi (present-day Burkina Faso) revealed several cowries drilled with holes, strung together and placed in the location of the head, possibly a woman, as a form of a headpiece.Cowries were also embedded with meaning exceeding the bounds of decorationthey were incorporated into rituals, ceremonies, objects, and became affiliated with symbols of fertility and protection. They also functioned as objects whose ownership demonstrated power and status. Further, at least by the 14th century, cowries were being used as currency in places like Gao (an inland city in present-day Mali).Sine Qua Non: Cowries as the Absolute ConditionA photograph of cowrie shells taken in Kolkata, West Bengal, India. Source: Wikimedia CommonsThe longstanding history of cowries in West Africa was noted by the Portuguese in the 16th century, who understood that the societies they encountered on the West African coast, especially in the Bight of Benin (including present-day Nigeria, Ghana, Benin, and Togo), highly valued these objects and used them as a tool of monetary exchange. The Portuguese brought the first European shipment of cowries from the Maldives to the Bight of Benin in 1515. By 1690, cowries were an instrumental unit of exchange for European merchants to buy enslaved West Africans bound for the Americas.Although cowrie shells were used in West Africa prior to European arrival, following the establishment of the Transatlantic Slave Trade, cowries filtered into West Africa in unprecedented numbers. In the late 17th century, cowries were 20-50 percent of the purchasing price of a person (Heath, p. 61). This was 10-30,000 shells. By 1770, it rose to 160-176,000 shells. Cowries became the sine qua non, the absolute condition, to carry out trade with coastal West African leaders (Hogendorn, p. 32).1899 Map of the Slave Trade of Africa by Harry Hamilton Johnston and John George Bartholomew. Source: New York Public LibraryCowries werent the only currency of the slave trade (Heath, p. 61). Other objects, consumables, and materials desired by West Africans leading the slave trade were also incorporated into trade transactions. Many of these objects came from European colonies throughout the Americas and Caribbean, and were often produced by enslaved West African laborthese were items such as sugar, alcohol, gold, and tobacco processed with molasses from Bahia (present-day Brazil). Gold dust would usually remain in the hands of Dahomean kings, while cowries would circulate in local markets and all strata of West African society.Counting the CowrieString of cowrie Shells from Ancient Egyptian Hepy Burial, ca. 1950-1885 BCE. Source: Metropolitan Museum of ArtBetween 1700 and 1790, 10 billion cowrie shells were shipped from British and Dutch ports, like London and Amsterdam, to West Africa. A 1780 settlement between the Yoruba Empire and Dahomey Kingdom was made in 400 bags of cowries, the equivalent of 1,600 at the time. Today, this is the same purchasing power as approximately 247,540. However, how would this amount of cowries be accounted for and organized in transactions?Once in West Africa, cowries would often be drilled with holes and placed on string in units of 40. A similar method of drilling and stringing cowries would also appear in East Africa. In the Buganda Kingdom of present-day Uganda, East African cowries were put on strings of 100, but could be halved or even broken down to units of five per string. In doing so, they could be used for transactions of varying value. Even in the above photo of a Shang Dynasty cowrie carved from bone, a visible hole was drilled in the back. This could suggest a similar way of keeping cowries organized, as far back as 1200 BCE or even earlier.North American CowriesWampam Shoulder Belt for a Powder Horn, 19th century. Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art, New YorkCowries even travelled as far as North America, where they were also used as currency in the fur trade between European settlers and merchants with various indigenous groups. Cowries were present at several indigenous burials in Queens, New York and Long Island. It is possible they were brought to North America by both the Dutch and French. Trading in a natural currency like shells would not have been foreign to European settlerstransactions already taking place between themselves and various Cherokee, Algonquian, and Iroquois Confederacy peoples who used wampam as a currency, which were tiny shell beads. Burials of the Arikara in South Dakota have also revealed over 44 cowries of the Maldivian monetaria moneta species, indicative of the spread of the trade in cowries.From the Maldives to the WorldA Ghanaian one-cent cedi, issued in 1979. Source: Wikimedia CommonsCowries from the Maldives appear all across the globe. They are present in regions as far as China in the east, and North America in the west, not to mention all the cultures and regions in between. Cowries were, and still are, a commodity that connected many regions and cultures throughout both time and space. They were the currency for transactional exchange for anything from objects to people. Both an economic tool and a cultural object, their significance remains today, albeit in more opaque ways. In West Africa, although cowries are no longer used as currency, the Ghanaian one cedi coin bears an image of a cowrie.SourcesBaker, C., & Phongpaichit, P. (2017). A History of Ayutthaya: Siam in the Early Modern World. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.Heath Barbara (2016). Commoditization, Consumption and Interpretive Complexity: The Contingent Role of Cowries in the Early Modern World. Presented at Society for Historical Archaeology, Washington, D.C.Hogendorn, J. S. (1981). A supplyside aspect of the African slave trade: The cowrie production and exports of the Maldives. Slavery & Abolition, 2 (1), 3152.0 Commentarii 0 Distribuiri 214 Views -

WWW.THECOLLECTOR.COMHow Did Napoleon Bonaparte Build the Greatest Army of Its Era?Napoleon Bonaparte dominated continental Europe as his French First Empire expanded at the start of the 19th century. Indeed, by 1808, Napoleon ruled an empire extending from Portugal to Poland. Napoleons army became the perfect instrument to execute the mobile and offensive style of war that military theorists dubbed Napoleonic. The army Napoleon forged was built upon ideas and innovations developed by French military theorists and commanders both before and during the French Revolutionary Wars (1792-1802). However, some of Napoleons strategies and tendencies contributed to the armys defeat and his downfall.Napoleon Bonaparte & the Royal and French Revolutionary ArmiesThe Battle of Valmy, September 20th, 1792, by Horace Vernet, 1826. Source: Wikimedia Commons/The National Gallery, LondonIn the 18th century, France boasted one of Europes largest and finest armies. However, defeat in the Seven Years War and mounting debts, stemming in part from Frances participation in the American Revolution, weakened the countrys military capabilities and helped set the stage for the French Revolution in 1789.Moreover, the Revolution plunged the countrys army into a crisis of command and organization. In the early years of the Revolution, many aristocrats serving as officers resigned or even defected to join one of Frances enemies.While initially this command shakeup weakened the military, it also paved the way for many capable ordinary soldiers to be promoted based on merit. One such commander was none other than the young Napoleon Bonaparte.According to historian Gunther Rothenberg, Napoleons military strategies and organizational changes blended reforms and innovations suggested by others in the late 18th century (2006, 24). France, both before and during the Revolution, produced several prominent military theorists, including Lazare Carnot and Swiss-born Antoine-Henri Jomini.Moreover, French theorists were particularly strong in developing innovative techniques and approaches to artillery, including the Gribeauval system. Napoleon specialized in artillery during his military education.Revolutionary France also built a modern conscription system to ensure the mass mobilization of French society for war, beginning with the Leve en masse in 1793.Below, well take a closer look at how Napoleon embraced and modified these earlier proposals as he built the Grande Arme.Napoleon Bonaparte as Commanding GeneralPortrait of Napoleon as King of Italy, by Andrea Appiani, 1805. Source: Wikimedia Commons/Kunsthistorisches Museum, ViennaNapoleon Bonapartes talent as a battlefield commander and propagandist was another crucial factor in Frances military success during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars.Napoleon was constantly focused on attacking his enemies and staying on the offensive. According to Gunther Rothenberg, the French emperor fought only three battles in his career on the defensive, all of which occurred between 1813 and 1814 (2006, 36).The success of most Napoleonic campaigns and battles depended on swift, long-distance marches and Napoleons ability to win meeting engagements. Historian J.P. Riley explains that a meeting engagement occurs when opposing forces on the march, lacking complete information about one another, unexpectedly collide. Napoleon generally welcomed chaos and confusion in the initial stages of battle (2000, 79).Propaganda was a key ingredient of Napoleons success as a commander. According to historian J. David Markham, Napoleon was a master of spin in our modern understanding (2003, 1). Beginning in Italy in 1796 and continuing throughout his career, Napoleon was involved in reporting his armys exploits. As Markham explains, Napoleon founded a newspaper for his Army of Italy in 1796-1797, where he shared stories to boost troop morale and bolster support in Paris. He continued this tradition through the bulletins he issued as Emperor (2003, 2-3).While he frequently exaggerated the extent of his victories and minimized his losses, Napoleons actual record on the battlefield was impressive. He also encouraged and sponsored engravings, prints, and even monumental art to tell the French people and the world about his exploits.Organizational InnovationsGeneral Bonaparte and his chief of staff, General Berthier, at the Battle of Marengo, by Joseph Boze, Robert Lefvre, and Carle Vernet, 1800-1801. Source: Wikimedia CommonsHistorian Gunther Rothenberg noted that the weapons, equipment, and troop types in the armies of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars remained largely unchanged from those of Frederick the Greats army several decades earlier. What had changed was the size of the armies, their organization, and how armies were deployed (2006, 24-25).Armies fought more battles in Europe during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars than in prior conflicts. For example, historian Tim Blanning notes that 713 battles were fought over the 23-year period between 1792 and 1815. There had only been 2,659 battles during the preceding three hundred years (2007, 643). The sheer volume of battles suggests that Napoleon and his opponents sought a complete victory.According to Gunther Rothenberg, this decisive outcome was dramatically different from the more limited objectives of earlier warfare in Europe. Most wars before the French Revolution ended without many bloody battles due to a lack of funds and resources (2006, 25).Napoleon adopted new methods of organization, including the establishment of a permanent corps structure. Before Napoleon, commanders used corps temporarily.A permanent corps structure essentially created miniature armies. This meant that each corps traveled along designated roads and had specific foraging areas to gather supplies. The permanent corps system thus permitted Napoleon to execute rapid, long-distance marches without clogging up roads and exhausting supplies.In terms of organization, Napoleon benefited from the work of his chief of staff, Alexandre Berthier. Berthier became one of Napoleons marshals despite rarely receiving a battlefield command.Napoleonic Warfare & WarsNapoleon during the Battle of Eylau, by Antoine-Jean Gros, 1808. Source: Wikimedia Commons/The Louvre Museum, ParisThe Napoleonic approach to war emphasized mobility, speed, and the concentration of superior numbers. The strategy behind this approach was to quickly and decisively crush enemy armies, thereby securing a rapid victory in a campaign or war.Napoleon and other French officers of the era favored aggressive tactics. We can see evidence of Napoleons method of waging war from the onset of his career as a commanding general during the Italian campaigns of 1796-1797. Here, Napoleon split the opposing Austrian and Piedmontese armies and defeated them separately. In less than one month, Napoleon forced Piedmont to seek peace and laid the foundation for a successful campaign against the Austrians.However, no campaign captured the essence of Napoleons way of war more than the Ulm-Austerlitz campaign of 1805. Historian Tim Blanning points out that the Austrian commander at Ulm, General Karl Mack, estimated it would take Napoleons army 80 days to reach his position. In reality, Napoleons troops covered the 300 miles (480 km) in just 13 days. As a result, the French achieved complete surprise and forced Macks surrender (2007, 655). Napoleon followed up the capture of Ulm with his greatest victory at Austerlitz on December 2, 1805.Napoleonic strategies had a profound impact on generations of military commanders, especially in the 19th century. For example, Napoleonic strategy and tactics dominated the military thinking and battlefield decisions of American Civil War officers, as well as those of the legendary Prussian commander Helmuth von Moltke the Elder.Meritocracy and Compromise: The MarshalatePortrait of Louis Nicolas Davout holding his marshals baton, by Tito Marzocchi de Bellucci after Pierre-Claude Gautherot, ca. 1852. Source: Wikimedia Commons/Palace of Versailles, Versailles, FranceOne reason for the success of Frances army and the expansion of Napoleons empire was the blending of the egalitarian and republican spirit of the French Revolution with the traditional privileges and structure of the pre-Revolution Ancien Rgime (old order).Historians Gregory Fremont-Barnes and Todd Fisher note that when he ruled as First Consul, Napoleon established the Legion of Honor to recognize excellence in various fields, both civilian and military. This award created a sort of nobility, but one based on merit (2004, 28).Few areas of Napoleonic France experienced this compromise between old and new as strongly as the military. Well take one specific example of this fusion as seen in Napoleons senior command structure: the marshalate.The rank of marshal in the French army was a symbol of the Ancien Rgime. Fremont-Barnes and Fisher explain that initially, Napoleon nominated 18 generals as marshals. They were selected based on ability, personal loyalty to Napoleon, or because they represented a political faction Napoleon wished to win (2004, 28).Fremont-Barnes and Fisher point out that Marshal Davout was the youngest of the original appointments. Marshal Bessires was a nobleman who was also intensely loyal to Napoleon (2004, 29-30). Other marshals, including Lannes and Massna, came from humble origins.Napoleons insistence on a centralized command, however, created problems for his marshals. For example, his orders prevented marshals from acting independently. In an era before instant communication and battlefields shrouded in smoke, Napoleons orders could arrive long after the situation a particular marshal faced had changed.Napoleons Soldiers I: LoyaltyMilitary Festival at Boulogne with Napoleon Distributing Stars of the Legion of Honor, print by Victor Adam, 19th century. Source: Wikimedia Commons/Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York CityHistorians Gregory Fremont-Barnes and Todd Fisher point out that a popular saying at the time suggested there was a marshals baton in every [soldiers] knapsack (2004, 28). Indeed, several of Napoleons marshals began their military careers as ordinary soldiers from the ranks.These words of encouragement inspired the troops of the Grande Arme, the name associated with Napoleons main army on campaign from 1805. As weve mentioned, Napoleon was a talented propagandist who helped cultivate his public image and legend. He was also a great motivator of his soldiers. According to historian Andrew Roberts, Napoleon taught ordinary people that they could make history (2014, 135).Napoleons soldiers also remained loyal followers because of their attachment to the regiment or unit in which they served. Napoleon recognized the value of legends and stories surrounding particular regiments as tools to inspire troops to fight and maintain discipline.Nevertheless, the life of a Napoleonic soldier was difficult. For example, soldiers often marched 20 miles (32 km) per day on campaign. According to historian Terry Crowdy, soldiers could march even greater distances if deemed necessary to execute Napoleons strategy (2002, 26).Napoleons emphasis on troops foraging for most supplies made sense during the lightning campaigns waged between 1796 and 1805. However, French troops suffered due to poor logistical situations in campaigns after 1805. According to historian Digby Smith, French supply systems broke down due to the increasingly larger armies, longer campaigns, and poor road conditions in places such as Spain and Eastern Europe (2010, 13).Napoleons Soldiers II: ConscriptionGrande Arme Infantry in 1812, by Carle Vernet, 1812. Source: Wikimedia CommonsThe bulk of Napoleons armies were not made up of volunteers, but of conscripts from across the empire. As weve seen with various organizational and tactical innovations of the Napoleonic era, conscription had also been utilized with great success during the French Revolution.Historian Terry Crowdy notes that Jourdans Law of 1798 made all unmarried males aged 20-25 liable for military service. As troop shortages became an issue due to the frequent conflicts of the Napoleonic era, it was common for conscripts to be borrowed from the following years draft class (2002, 6). As a result, Napoleons armies grew younger and more inexperienced, particularly in the campaigns of 1813-1815.Departure of the Conscripts in 1807, by Louis-Lopold Boilly, ca. 1808. Source: Muse Carnavalet Wikimedia Commons/Muse Carnavalet, ParisPerhaps the most famous conscript class was the Marie-Louises. Crowdy notes that these teenage recruits derived their nickname from Napoleons second wife, Empress Marie-Louise, who signed the conscription decree in Napoleons absence during the 1812 Russian campaign (2002, 62).Conscription was deeply unpopular and became a source of resistance in many territories conquered by France. Many Germans, Italians, Swiss, and others were forced to join units attached to the Grande Arme.Occasionally, resistance to conscription helped fuel revolts against Napoleonic rule. In 1809-1810, Andreas Hofer led an Austrian-backed peasant revolt in Tyrol against Napoleons ally, Bavaria. Hofers Tyroleans resented Bavarian taxation and conscription policies, which were designed to support Napoleon against Austria, Tyrols traditional ruler. However, historians Gregory Fremont-Barnes and Todd Fisher explain that French and Bavarian forces crushed the revolt, and Hofer was executed in 1810 (2004, 144).The Decline and Defeat of the Napoleonic EmpireNapoleon near Borodino, by Vasily Vereshchagin, 1897. Source: Wikimedia Commons/State Historical Museum, MoscowResistance to conscription proved to be one of many problems Napoleonic France faced by the time the Grande Arme invaded Russia in the summer of 1812.According to historian Digby Smith, of the roughly 325,000 troops in the Grande Arme at the onset of the disastrous Russian campaign of 1812, only 155,400 were French (2010, 18). The size of non-French troops suggests, in part, the extent to which Napoleon controlled vast swaths of Europe. However, it also highlights the immense losses suffered by French soldiers during the years of bloody battles.Moreover, many of Napoleons best French forces were tied down in Spain and thus unable to join the Russian campaign. Spain indeed was another major factor in Napoleons eventual defeat. British forces, along with their Spanish and Portuguese allies, defeated multiple French armies in Spain and Portugal.Napoleon also failed to appreciate that his enemies could emulate his organization and tactics, thereby turning the tables on the French. Once coalition partners like Austria, Britain, Prussia, and Russia could concentrate their forces, it became difficult for French armies to achieve victory, even with a noted military genius like Napoleon as their commander.Although defeated in successive campaigns between late 1813 and June 1815, Napoleons Grande Arme left a lasting impact on modern militaries worldwide. Indeed, Napoleons campaigns are still taught in military academies. Moreover, the permanent corps system remains the main form of military organization in the 21st century.References and Further ReadingBlanning, T. (2007). The Pursuit of Glory: The Five Revolutions that Made Modern Europe, 1648-1815. Penguin.Crowdy, T. (2002). French Napoleonic Infantryman, 1803-1815. Osprey.Fremont-Barnes, G. and T. Fisher. (2004). The Napoleonic Wars: The Rise and Fall of an Empire. Osprey.Markham, J.D. (2003). Imperial Glory: The Bulletins of Napoleons Grande Arme 1805-1814. Greenhill Books.Riley, J. (2000). Napoleon and the World War of 1813: Lessons in Coalition Warfighting. Cass.Roberts, A. (2014). Napoleon the Great. Penguin.Rothenberg, G. E. (2006). The Napoleonic Wars. Collins. (Original work published 1999).Smith, D. (2010). Armies of 1812: The Grand Arme and the Armies of Austria, Prussia, Russia, and Turkey. Spellmount.0 Commentarii 0 Distribuiri 215 Views