0 Comentários

0 Compartilhamentos

127 Visualizações

Diretório

Elevate your Sngine platform to new levels with plugins from YubNub Digital Media!

-

Faça o login para curtir, compartilhar e comentar!

-

New soulslike Wuchang Fallen Feathers soars on Steam, but user reviews are awfulNew soulslike Wuchang Fallen Feathers soars on Steam, but user reviews are awful As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases and other affiliate schemes. Learn more. Stylish soulslike Wuchang: Fallen Feathers is already soaring up the Steam charts, but it's also the latest game to suffer a major user-score...0 Comentários 0 Compartilhamentos 1KB Visualizações

-

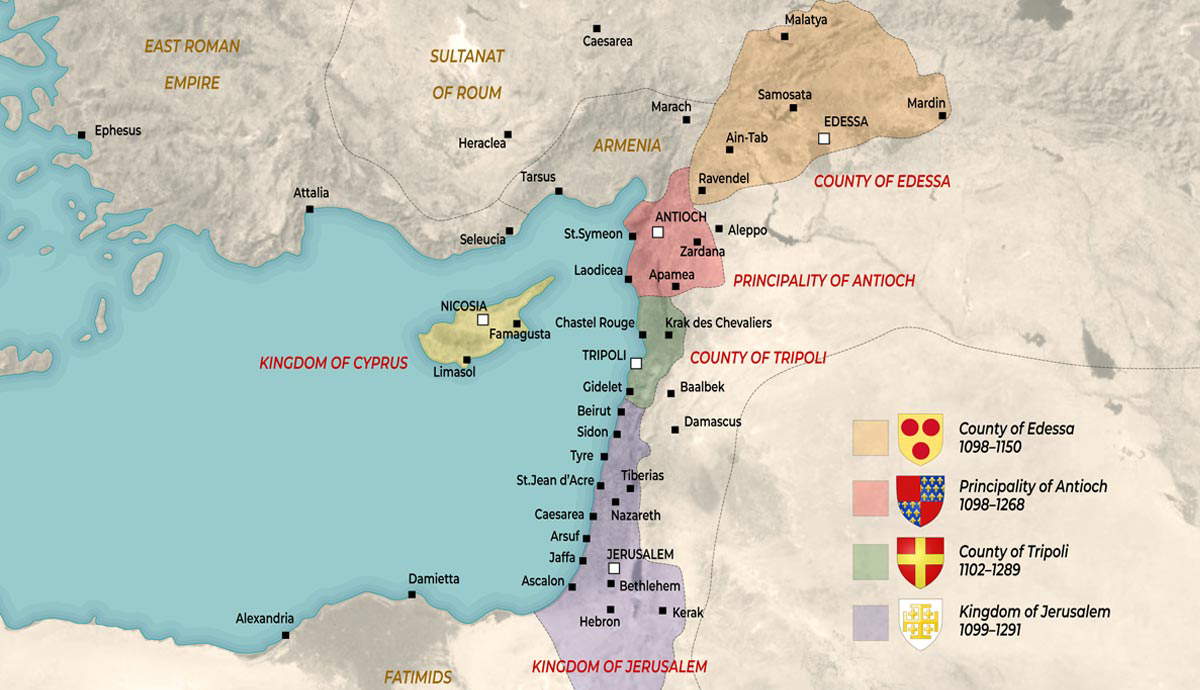

WWW.THECOLLECTOR.COMThe Four Crusader States in the Holy LandAs a site of great significance for three world religions, the Levant has been subject to brutal wars over the centuries. When Pope Urban II launched the First Crusade in 1095, the main target was Jerusalem and the Holy Land. During the First Crusade, the Christians successfully established four Crusader states, known collectively as Outremer. While the Christian territory shrank over time, they maintained a presence in the Holy Land for almost two centuries until what remained of the Kingdom of Jerusalem was conquered by the Egyptian Mamluks in 1291.The Four Crusader States in the Holy LandKingdomYear of EstablishmentYear of CollapseCause of collapseCounty of Edessa10981144Conquered by the ZengidsPrincipality of Antioch10981268Conquered by the Mamluk SultanateCounty of Tripoli11021289Conquered by the Mamluk SultanateKingdom of Jerusalem10991291Conquered by the Mamluk SultanatePope Urban II and the First CrusadePope Urban II preaching the First Crusade in the Square of Clermont, Francesco Hayez, 1835. Source: Wikimedia CommonsThe Holy Land had been under Islamic rule ever since the Arab conquests of the 7th century CE. They generally left Jews and Christians alone, but the rise of the Seljuk Turks concerned Christian leaders in Europe. The Byzantine Empire, under the leadership of Emperor Alexios I Komnenos, began a war with the Seljuks to push them out of Anatolia and requested support from the Papacy. Notwithstanding his prior conflicts with the Normans, Alexioss plea was earnestly received by the Council of Piacenza, which heard reports of the brutal massacres of Levantine Christians by the Seljuks.In 1095, Pope Urban hosted the Council of Clermont and called for an army of Christians to march on the Holy Land and drive out the Seljuks. Urbans motivations were varied: he wished to cement Romes authority over European Christianity and he hoped that, by coming to the aid of Eastern churches, he could heal the Great Schism between Roman Catholicism and Byzantine Orthodoxy. Urban was a Frenchman and he began touring his homeland seeking French nobles to lead this expedition.The First Crusade also became known as the Peoples Crusade because of the large-scale involvement of Commoners in its ranks. A French priest from Amiens known as Pierre lErmite, or Peter the Hermite, led an army through the Holy Roman Empire and southeastern Europe. Another more professional force led by the leading knights of Europe also marched on a similar path.Establishment of the Crusader StatesBaldwin of Boulogne entering Edessa in February 1098, by Joseph-Nicolas Robert-Fleury, 1840. Source: Wikimedia CommonsOne of the principal goals of the Council of Clermont was to establish Christian kingdoms in the Levant and Anatolia to counteract the Seljuk advances and the spread of Islam.After advancing into Anatolia along with the Byzantine army, the Crusaders turned southwards and rapidly advanced against major Seljuk strongholds. Nicaea was captured in 1097, Edessa in March 1098, and Antioch shortly after in June. The main target of the Crusaders, Jerusalem, was taken in a siege in 1099.Reinforcements ferried to the Levant by the Italian city-states of Venice, Genoa, and Pisa assisted the Christian advances. By 1109, they controlled Tripoli and seized several more Levantine cities in subsequent years.The successes of the Crusaders were stunning considering that they were hundreds of miles from home. Local Christian communities varied in their reaction to these advances. For instance, some Armenians helped the Crusaders capture Antioch. In other cases, local Christian communities allied with the Seljuks. This created some tensions between these communities and the Crusaders. Once the conquests were complete, the Christian nobles who led their followers to the Levant started to establish various different feudal states.The first Crusader state established was the Country of Edessa under the leadership of Baldwin of Boulogne. The second one was the Principality of Antioch, led by Bohemund of Normandy. The most powerful of the four was the Kingdom of Jerusalem, founded by Godfrey of Bouillon. Lastly, the County of Tripoli was established after its capture by Raymond of Toulouse and was the most independent of all four states.Governance in the Crusader StatesMap of the Crusader states created after the First Crusade. Source: TheCollectorAll four Crusader states had a similar form of political administration: they based their leadership on European feudal hierarchies. At the top of the realm was a king or prince, depending on the state. They ruled over a court of nobles, known as the High Court or Haute Cour. This court had much more power than its European counterparts and could elect or depose a regent depending on the circumstances. Members of the court were in charge of separate fiefdoms similar to what existed in medieval Europe.The Kingdom of Jerusalem was the most powerful of the four kingdoms owing to the strength of its military and the symbolic significance of ruling over Jerusalem. However, all four states struggled with the lack of effective governing structures and internal chaos. They relied heavily on the support of the Papacy and European monarchies to keep them stable in the face of attacks by different Muslim states. Their economies existed due to limited trade ties facilitated by the Italian city-states and taxes collected by the various nobles from the residents of their feudatories.The Catholic Church was the most powerful institution in medieval Europe and it had a strong influence in the Levant. Various popes sent money and resources to each of the four states and ensured that they received support from Europe. At the same time, it competed with the Eastern Church for followers in the region. When this support dried up, the polities in Outremer became more precarious.Demographics of the Crusader StatesRemnants of a Crusader castle in Sidon, Lebanon, where many Frankish settlers lived after emigrating, 2016. Source: American Society of Overseas ResearchThe four Crusader states were characterized by diverse and often stratified populations. Though ruled by Western European Christian elites, the vast majority of inhabitants were local non-Latin peoples. Catholics, primarily from France, Italy, and the Holy Roman Empire, formed the military and political aristocracy but remained a small minority. They settled mostly in urban centers and fortified positions, often establishing separate quarters from the local population. Catholic settlers included knights, clergy, merchants, and pilgrims who arrived during or shortly after the First Crusade.The majority population consisted of Eastern Christians, such as Greek Orthodox, Armenian Apostolic, Syrian Orthodox, and Maronite Christians, Muslims (Sunni and Shia), and Jews. Eastern Christians often served as bureaucrats, merchants, and farmers. While relations with Latin rulers were sometimes strained, they were often co-opted into administrative roles. Muslims, who made up a large share of the rural and some urban population, were subject to higher taxes and at times legal restrictions, but many continued their lives under Crusader rule with a degree of continuity.Armenians, particularly in the County of Edessa, were influential allies. Many of them were involved in state administration. Jews were a smaller group, often confined to specific towns or quarters. They often suffered from Christian persecution based on the idea that they were responsible for the death of Jesus. Overall, the Crusader states were complex, multilingual societies shaped by cooperation, coexistence, and periodic conflict among their many ethnic and religious communities.The Crusading Orders19th-century print of Jacques de Molay, the last Grand Master of the Templars. Source: Wikimedia Commons via Bibliothque Nationale de FranceTo maintain order and defend against Seljuk and Mamluk attacks on Outremer, each Crusader state developed armies and stationed them in castles and outposts on the periphery. Each ruler had barons under their command who had anywhere between 10 and 100 knights as subordinates.Crusader knights formed several military orders, the most famous of which was called the Knights Templar. Most knights fought on horseback, creating a formidable cavalry force that often overwhelmed the poorly-equipped Seljuk armies. The infantry consisted of men armed with spears, short swords, or longbows/crossbows that sought to exploit any breach created by the cavalry.Most crusader armies numbered only a couple of thousand men. Except for the First Crusade, their armies were often outnumbered by the larger Muslim armies that attacked them. For instance, the Muslim leader Saladin organized a force of 20,000 men after uniting the Muslims of Egypt, Syria, and parts of Iraq. The Kingdom of Jerusalem, being the most populous Crusader state, could field the largest force, but even that paled in comparison to the Seljuk or Mamluk forces.While the barons and knights were generally European, much of the infantry and mounted archers (Turcopoles) were recruited from local Christian communities. Armenian, Syrian, Maronite, and Palestinian Christians contributed large numbers of men to the Crusader armies. They served alongside European Christians who traveled to the Levant to fight against the Muslim armies during subsequent crusades. By the end of the 12th century, the Crusader states had become reliant on local levies to address their manpower shortages; even this did not prove enough.Collapse of the Four KingdomsSaladins conquest of Jerusalem. Print by Jan Lukyen, 1683. Source: World History EncyclopediaThe collapse of the four Crusader states was a gradual process driven by internal weakness, lack of support from Europe, and increasingly effective Muslim resistance. The first to fall was the County of Edessa, captured by Zengi of Mosul in 1144. This event shocked Europe and triggered the unsuccessful Second Crusade. Edessas position far from the coast made it especially vulnerable. The remaining states survived but were shaken.Over the next century, the Kingdom of Jerusalem suffered from dynastic instability, overreliance on military orders like the Templars and Hospitallers, and the decline in crusading zeal in Europe. Its pivotal defeat came in 1187, when Saladin defeated the Crusaders at the Battle of Hattin and recaptured Jerusalem, leaving only a few coastal cities under Christian control.Though the Christians recaptured some territory such as the port of Acre during the Third Crusade, the Kingdom of Jerusalem never fully recovered. The Principality of Antioch and County of Tripoli held on until the late 13th century but were weakened by Mongol invasions and increasing pressure from the Mamluk Sultanate, which became the dominant Muslim power in the region. Antioch fell in 1268 to Sultan Baibars, a Mamluk Sultan from Egypt, and Tripoli followed in 1289.Finally, the once-mighty Crusader presence ended with the fall of Acre in 1291, marking the collapse of the Kingdom of Jerusalem and the end of Crusader rule in the Levant. The remaining Catholic enclaves were evacuated, and the region returned to Muslim control. The four kingdoms left a mark on the Levant, and the imposing ruins of their castles and fortresses can still be seen today.0 Comentários 0 Compartilhamentos 116 Visualizações

WWW.THECOLLECTOR.COMThe Four Crusader States in the Holy LandAs a site of great significance for three world religions, the Levant has been subject to brutal wars over the centuries. When Pope Urban II launched the First Crusade in 1095, the main target was Jerusalem and the Holy Land. During the First Crusade, the Christians successfully established four Crusader states, known collectively as Outremer. While the Christian territory shrank over time, they maintained a presence in the Holy Land for almost two centuries until what remained of the Kingdom of Jerusalem was conquered by the Egyptian Mamluks in 1291.The Four Crusader States in the Holy LandKingdomYear of EstablishmentYear of CollapseCause of collapseCounty of Edessa10981144Conquered by the ZengidsPrincipality of Antioch10981268Conquered by the Mamluk SultanateCounty of Tripoli11021289Conquered by the Mamluk SultanateKingdom of Jerusalem10991291Conquered by the Mamluk SultanatePope Urban II and the First CrusadePope Urban II preaching the First Crusade in the Square of Clermont, Francesco Hayez, 1835. Source: Wikimedia CommonsThe Holy Land had been under Islamic rule ever since the Arab conquests of the 7th century CE. They generally left Jews and Christians alone, but the rise of the Seljuk Turks concerned Christian leaders in Europe. The Byzantine Empire, under the leadership of Emperor Alexios I Komnenos, began a war with the Seljuks to push them out of Anatolia and requested support from the Papacy. Notwithstanding his prior conflicts with the Normans, Alexioss plea was earnestly received by the Council of Piacenza, which heard reports of the brutal massacres of Levantine Christians by the Seljuks.In 1095, Pope Urban hosted the Council of Clermont and called for an army of Christians to march on the Holy Land and drive out the Seljuks. Urbans motivations were varied: he wished to cement Romes authority over European Christianity and he hoped that, by coming to the aid of Eastern churches, he could heal the Great Schism between Roman Catholicism and Byzantine Orthodoxy. Urban was a Frenchman and he began touring his homeland seeking French nobles to lead this expedition.The First Crusade also became known as the Peoples Crusade because of the large-scale involvement of Commoners in its ranks. A French priest from Amiens known as Pierre lErmite, or Peter the Hermite, led an army through the Holy Roman Empire and southeastern Europe. Another more professional force led by the leading knights of Europe also marched on a similar path.Establishment of the Crusader StatesBaldwin of Boulogne entering Edessa in February 1098, by Joseph-Nicolas Robert-Fleury, 1840. Source: Wikimedia CommonsOne of the principal goals of the Council of Clermont was to establish Christian kingdoms in the Levant and Anatolia to counteract the Seljuk advances and the spread of Islam.After advancing into Anatolia along with the Byzantine army, the Crusaders turned southwards and rapidly advanced against major Seljuk strongholds. Nicaea was captured in 1097, Edessa in March 1098, and Antioch shortly after in June. The main target of the Crusaders, Jerusalem, was taken in a siege in 1099.Reinforcements ferried to the Levant by the Italian city-states of Venice, Genoa, and Pisa assisted the Christian advances. By 1109, they controlled Tripoli and seized several more Levantine cities in subsequent years.The successes of the Crusaders were stunning considering that they were hundreds of miles from home. Local Christian communities varied in their reaction to these advances. For instance, some Armenians helped the Crusaders capture Antioch. In other cases, local Christian communities allied with the Seljuks. This created some tensions between these communities and the Crusaders. Once the conquests were complete, the Christian nobles who led their followers to the Levant started to establish various different feudal states.The first Crusader state established was the Country of Edessa under the leadership of Baldwin of Boulogne. The second one was the Principality of Antioch, led by Bohemund of Normandy. The most powerful of the four was the Kingdom of Jerusalem, founded by Godfrey of Bouillon. Lastly, the County of Tripoli was established after its capture by Raymond of Toulouse and was the most independent of all four states.Governance in the Crusader StatesMap of the Crusader states created after the First Crusade. Source: TheCollectorAll four Crusader states had a similar form of political administration: they based their leadership on European feudal hierarchies. At the top of the realm was a king or prince, depending on the state. They ruled over a court of nobles, known as the High Court or Haute Cour. This court had much more power than its European counterparts and could elect or depose a regent depending on the circumstances. Members of the court were in charge of separate fiefdoms similar to what existed in medieval Europe.The Kingdom of Jerusalem was the most powerful of the four kingdoms owing to the strength of its military and the symbolic significance of ruling over Jerusalem. However, all four states struggled with the lack of effective governing structures and internal chaos. They relied heavily on the support of the Papacy and European monarchies to keep them stable in the face of attacks by different Muslim states. Their economies existed due to limited trade ties facilitated by the Italian city-states and taxes collected by the various nobles from the residents of their feudatories.The Catholic Church was the most powerful institution in medieval Europe and it had a strong influence in the Levant. Various popes sent money and resources to each of the four states and ensured that they received support from Europe. At the same time, it competed with the Eastern Church for followers in the region. When this support dried up, the polities in Outremer became more precarious.Demographics of the Crusader StatesRemnants of a Crusader castle in Sidon, Lebanon, where many Frankish settlers lived after emigrating, 2016. Source: American Society of Overseas ResearchThe four Crusader states were characterized by diverse and often stratified populations. Though ruled by Western European Christian elites, the vast majority of inhabitants were local non-Latin peoples. Catholics, primarily from France, Italy, and the Holy Roman Empire, formed the military and political aristocracy but remained a small minority. They settled mostly in urban centers and fortified positions, often establishing separate quarters from the local population. Catholic settlers included knights, clergy, merchants, and pilgrims who arrived during or shortly after the First Crusade.The majority population consisted of Eastern Christians, such as Greek Orthodox, Armenian Apostolic, Syrian Orthodox, and Maronite Christians, Muslims (Sunni and Shia), and Jews. Eastern Christians often served as bureaucrats, merchants, and farmers. While relations with Latin rulers were sometimes strained, they were often co-opted into administrative roles. Muslims, who made up a large share of the rural and some urban population, were subject to higher taxes and at times legal restrictions, but many continued their lives under Crusader rule with a degree of continuity.Armenians, particularly in the County of Edessa, were influential allies. Many of them were involved in state administration. Jews were a smaller group, often confined to specific towns or quarters. They often suffered from Christian persecution based on the idea that they were responsible for the death of Jesus. Overall, the Crusader states were complex, multilingual societies shaped by cooperation, coexistence, and periodic conflict among their many ethnic and religious communities.The Crusading Orders19th-century print of Jacques de Molay, the last Grand Master of the Templars. Source: Wikimedia Commons via Bibliothque Nationale de FranceTo maintain order and defend against Seljuk and Mamluk attacks on Outremer, each Crusader state developed armies and stationed them in castles and outposts on the periphery. Each ruler had barons under their command who had anywhere between 10 and 100 knights as subordinates.Crusader knights formed several military orders, the most famous of which was called the Knights Templar. Most knights fought on horseback, creating a formidable cavalry force that often overwhelmed the poorly-equipped Seljuk armies. The infantry consisted of men armed with spears, short swords, or longbows/crossbows that sought to exploit any breach created by the cavalry.Most crusader armies numbered only a couple of thousand men. Except for the First Crusade, their armies were often outnumbered by the larger Muslim armies that attacked them. For instance, the Muslim leader Saladin organized a force of 20,000 men after uniting the Muslims of Egypt, Syria, and parts of Iraq. The Kingdom of Jerusalem, being the most populous Crusader state, could field the largest force, but even that paled in comparison to the Seljuk or Mamluk forces.While the barons and knights were generally European, much of the infantry and mounted archers (Turcopoles) were recruited from local Christian communities. Armenian, Syrian, Maronite, and Palestinian Christians contributed large numbers of men to the Crusader armies. They served alongside European Christians who traveled to the Levant to fight against the Muslim armies during subsequent crusades. By the end of the 12th century, the Crusader states had become reliant on local levies to address their manpower shortages; even this did not prove enough.Collapse of the Four KingdomsSaladins conquest of Jerusalem. Print by Jan Lukyen, 1683. Source: World History EncyclopediaThe collapse of the four Crusader states was a gradual process driven by internal weakness, lack of support from Europe, and increasingly effective Muslim resistance. The first to fall was the County of Edessa, captured by Zengi of Mosul in 1144. This event shocked Europe and triggered the unsuccessful Second Crusade. Edessas position far from the coast made it especially vulnerable. The remaining states survived but were shaken.Over the next century, the Kingdom of Jerusalem suffered from dynastic instability, overreliance on military orders like the Templars and Hospitallers, and the decline in crusading zeal in Europe. Its pivotal defeat came in 1187, when Saladin defeated the Crusaders at the Battle of Hattin and recaptured Jerusalem, leaving only a few coastal cities under Christian control.Though the Christians recaptured some territory such as the port of Acre during the Third Crusade, the Kingdom of Jerusalem never fully recovered. The Principality of Antioch and County of Tripoli held on until the late 13th century but were weakened by Mongol invasions and increasing pressure from the Mamluk Sultanate, which became the dominant Muslim power in the region. Antioch fell in 1268 to Sultan Baibars, a Mamluk Sultan from Egypt, and Tripoli followed in 1289.Finally, the once-mighty Crusader presence ended with the fall of Acre in 1291, marking the collapse of the Kingdom of Jerusalem and the end of Crusader rule in the Levant. The remaining Catholic enclaves were evacuated, and the region returned to Muslim control. The four kingdoms left a mark on the Levant, and the imposing ruins of their castles and fortresses can still be seen today.0 Comentários 0 Compartilhamentos 116 Visualizações -

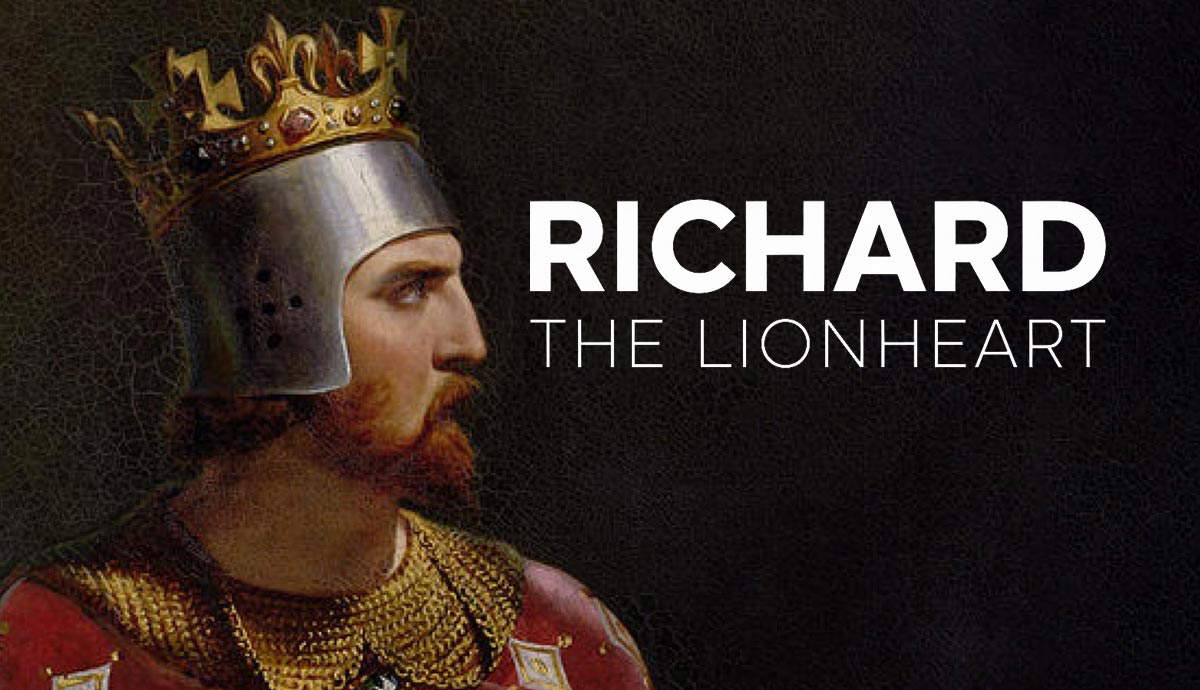

WWW.THECOLLECTOR.COMHow Did Richard the Lionheart Become Englands Most Famous King?Richard I (1157-1199), the Lionheart, is celebrated as Englands great warrior king, a man who embodied the ideals of medieval chivalry and nobility. Historically, however, Richard was notorious for having had little interest in England or the Englishand in truth, he was never supposed to rule England at all. Yet despite this, he is still beloved as an English national icon and one of the countrys most beloved rulers. How then did Richard become King, and why is he so beloved in a country he apparently cared little for?Born to Rule, but Not in EnglandThe iconic statue of Richard I outside the Houses of Parliament in London. Source: Wikimedia CommonsRichards re-appraisal as a very un-English king is already well known. All told, he only spent six months in England and spent almost all his reign abroad on Crusade and other ventures that nearly bankrupted the country. So how did such an un-English man become king of England? To understand that we must look back at his family and origins.Born, interestingly enough, in Oxford, Richard was the third oldest child and second to survive infancy, of Henry II of England and Eleanor, Duchess of Aquitaine. His parents were the ultimate medieval power couple. Between them, they ruled over a vast dominion known as the Angevin Empire, which included England and much of modern-day France, Wales, Ireland, and Scotland. Richards father was an energetic and ambitious king, and his mother was a brilliant political operator and famous cultural patron.Richard spent his early years between England and his parents French territories receiving a courtly education. Far from the military meathead as he is sometimes portrayed, Richard was a cultured prince who even wrote poetry, literacy being a notable gift at the time. He spoke both Court French and Occitan (his mothers first language) but it is unknown if he ever spoke English.Richard was groomed to be an ideal medieval ruler, but not of England, which was to be inherited by his older brother, Henry. Instead, Richard was to inherit his mothers Duchy of Aquitaine. In other words, Richard was born not to be King of England but an Anglo-Norman French duke. By the late 1160s, Richard was immersed in the famous cultural court of his mothers Aquitanian estates, his future seemingly pointed very much away from England.Duke of AquitaineLouis VII of France, 1375-80. Source: BnFIn 1167, Richard pledged homage as future Duke of Aquitaine to King Louis VII of France. In practice, Richard was of course subservient to his father, though Henry was technically also a vassal of Louis due to his French and Norman holdings. The complex legal framework of feudal vassalage aside, Richard was soon given more practical responsibilities.In 1171 Henry II decided his sons should prepare for their succession. His first son was elevated to co-monarch, becoming known as Henry the Young King to ease confusion. Meanwhile, Richard was officially made Duke of Aquitaine at the tender age of 14. Although Eleanor still had a hand in governance, Richard undertook important duties while gaining ruling work experience.However, in 1173 Henry the Young King rebelled against his father for taking the revenue earned by the Young Kings new positions for himself. Richard joined his brother, supported by their mother, who had all but legally separated from Henry II due to infidelity, alongside his Aquitanian vassals and with King Louis also providing support. Barely 15 years old, Richard was now a military commander in this family squabble-turned-international conflict.Henry II, 1523 portrait. Source: Wikimedia CommonsDespite his youth, Richard showed an impressive aptitude for warfare, but in 1174 Henry II made a separate peace with Louis, and then captured Eleanor, forcing the brothers to capitulate. Their father forgave them but kept their mother in custody, to ensure continued compliance. Henry did, however, make one demand of his second son, ordering Richard to pacify the Aquitanian lords who were still in rebellion.Whether or not Richard felt any qualms about betraying the subjects who had previously supported him, he still dutifully obeyed his father. Richards military reputation continued to grow as a tactician and warrior, and soon he gained his magnificent epithet: Cur de Lion, or the Lionheart, for his bravery and skill.However, Richards lack of enthusiasm led to a weak pacification policy of all sticks and no carrots. As a result, he faced repeated Aquitanian uprisings from 1175 to the early 1180s. He also faced threats from Frances new king Philippe II and even his brothers Henry and Geoffrey of Brittany, though his father did his best to mediate these conflicts.Warrior Duke to Unintended HeirDetail of a miniature of Richard I doing homage to Philippe for Normandy, 12th-13th century. Source: PicrylRichards life was one of constant diplomatic, political, and military maneuvering as he struggled to assert himself in the violent world of the medieval elite. Yet he seemed more than up to the task and may well have become a powerful and respected French-Aquitanian Duke. Then, in 1183, the Young King died suddenly of typhus and Richards life, not to mention the fate of the Angevin Empire, was turned upside down.Richard was now heir to the throne, with all the responsibilities that came with it. Though he had likely returned to England on occasion, his main focus had been on Aquitaine. He had spent his whole life so far learning to be a French duke but was now to become a king. The two certainly had transferable skills but a provincial vassal was on a very different level to being the sole ruler of a vast multinational dominion. Furthermore, to rebalance his empire, Henry II demanded Richard to hand over Aquitaine to his younger brother John. Richard refused to even consider it, even after Henry released Eleanor to negotiate the handover with him.Some have seen Richards refusal as a sign that he would have preferred to keep Aquitaine than take the English crown. However, after spending all his life preparing to rule Aquitaine, and almost a decade fighting over it, Richards refusal is understandable. Strategically, it was also a vital asset and a strong powerbase for Richard, which his brother could use to challenge him in the future.The Angevin Empire in 1154. Source: Wikimedia CommonsFor four years, Richard stubbornly refused to give up Aquitaine, his defiance teetering dangerously close to open rebellion. In 1187, things escalated dramatically when Richard signed up for the newly called Third Crusade as penance for the brutality of his previous actions against his Aquitanian vassals. Henry II refused to let Richard risk his life in the Holy Land and moved from diplomatic pressure to outright force.However, Richard was well-liked by Henrys other vassals, and many sided with him, the worst betrayal being when John, Henrys favorite son, took his brothers side. Henry even went so far as to ask Philippe II of France to assist him. However, in a display of his budding political abilities, Richard managed to secure Philippe as his ally instead. In 1189, Richard and Philippe defeated Henry at the Battle of Ballans and two days later Henry died, it was claimed, of a broken heart.Absent Ruler of an EmpireRichard I, by Merry-Joseph Blondel, 19th century. Source: Wikimedia CommonsSo that is how Richard, the second son of a king and destined all his life to be a French duke, suddenly found himself king of England. Or more accurately, ruler of the Angevin Empire. Though the king of England was his senior title, Richards dominion was far more than just England. Westminster may have been his capital, but Rouen, Chinon, Poitiers, and Limoges were all major centers of governance and administration.So how did Richard fare as a ruler? Notoriously, barely a year after his coronation, Richard left his kingdom to go on Crusade, not exactly the most responsible action for a fledgling king. However, Richard had signed up for the Crusade before becoming king, and backing out would have been a terrible loss of face. Nor was he the only major European ruler to go, both Philippe of France and the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa had also taken the cross. In fact, going on Crusade was a powerful display of Richards power and his dominions prestige.Yet Richards crusading venture had mixed results. Militarily, he won several victories and famously went toe-to-toe with the legendary Saladin. However, he fell out with Philippe and the Duke of Austria, who commanded the Holy Roman Empires contingent after Barbarossa died. As a result, they both abandoned the Crusade, forcing Richard to make peace with Saladin and give up on his dream of taking Jerusalem. Yet on return from the Crusade, things only got worse.Saladin, made in Paris, 1584. Source: The British MuseumWhile heading home, in autumn 1193, Richard was blown off course and had to travel through Austria. However, he was recognized and kidnapped by the Duke of Austria, who then sold him to the new Holy Roman Emperor, Henry VI, who demanded a ransom of 150,000 marks, more than twice the annual royal revenue. After several months the money was finally raised through a one-off tax and Richard returned to his kingdom in early 1194only to find it a total mess.After hearing news of Richards capture, John made a bid for the throne, while a newly returned King Philippe attacked Richards French territory. Normandy and Anjou were in serious jeopardy, Aquitaine was again in rebellion and mercenaries in Johns pay had taken control of several parts of England. It was a small miracle that his mother and the administration ruling in Richards absence were even able to raise the funds to secure his release.A Reign Cut ShortThe remains of Chteau Gaillard in France, an imposing castle built by Richard, who may have also been its chief architect as well. Source: Wikimedia CommonsRichard returned to a financially drained and politically unstable kingdom. Thankfully on his triumphal return to England, Johns attempted coup collapsed almost immediately. After the last of his mercenary forces were scoured from their strongholds, Richard magnanimously forgave his brother. With England put to rights, Richard swiftly moved to France to deal with Philippe.Richard managed to militarily and diplomatically outfox Philippe, forming a coalition of other powerful lords, such as the Duke of Flanders, to assist him as he defeated Philippe in a series of brilliant campaigns to retake his lost territory. Richard even found the time to design and construct the Chteau Gaillard, a state-of-the-art fortress that dominated the Seine Valley and controlled the frontier with France.On the eve of the 12th century, Richards rejuvenated Angevin Empire was the undisputed great power of Western Europe. However, in March 1199, as Richard was besieging Chteau de Chlus-Chabrol, the home of yet another rebellious Aquitanian lord, he was hit in the shoulder by a speculative crossbow bolt from the castle walls. The wound became infected and three days later, Richard died in his mothers arms. So, he passed at 42, his life cut short in its primebut then again Richard, always the warrior king, had lived by the sword.Richard the Lionheart Statue at Fecamp Abbey, France. Source: Wikimedia CommonsFor most of his adult life, Richard had been engaged in business outside of England and famously he spent very little of his decade-long reign in England itself. Yet at the time of his death, he was a well-loved king and despite historiographical pushback, English infatuation with him has only grown. His motto Dieu et mon Droit (God and my Right) is still the motto of the Royal Family, and his coat of arms of three lions, a national symbol of England. Why does England love the king who shouldnt have been? More pertinently, was he as great a king as popularly believed?Historian Stephen Runciman described Richard as a bad son and a bad king, but a gallant and splendid soldier. Yet there is much to be considered in appraising Richards actual rule.The Glamor of the Warrior KingThe three lions had been a symbol of the previous Norman Kings of England, but Richard was the first to use this stylization. Source: Wikimedia CommonsIn one regard at least, the adoration of Richard is understandablehe was an astonishingly glamorous king. Richard was the avatar of medieval chivalry, embodying all the traits popularized by troubadours and romantic poets of the time. There are accounts critical of his behavior but many of these were sponsored by his enemies and even they often acknowledge Richards splendor. By most accounts, he was good-looking, eloquent, and a generous lord, though prone to thoughtlessness and vanity at times.He was not only a brilliant general and warrior but was dedicated to his troops and often put himself in danger for their safety. While he did commit acts of brutality, they were not the exception for the time and by and large, Richard was famous for being courteous to his enemies on and off the field. Famously, he even forgave the arbalest who shot him while on his deathbed. Though Richard spent little time in England, his military glory, especially the Crusade, greatly boosted contemporary English prestige.Richard the lionheart, floortile, 1250s. Source: British MuseumRegarding the little time he spent in England, it must be remembered that his domain included far more than just England. Richards absence from England does not mean an absence of kingly qualities. The fact is, however, Richard died without doing much actual ruling because wars, of his own creation or not, dominated his reign.Yet, Richards military career and charisma do not mean he was a capable ruler. In his time as king, he spent the royal treasury rather than saved its coin, but the kingdom was prosperous enough to recover even from the extra taxes levied to pay his ransom, though many Church chroniclers criticized him fiercely for levying taxes on the Church to repay this debt. He was certainly not the great statesman and reformer his father had been. However, he was not a tyrant or political failure. He did sell offices of state to the highest bidder, but this was not a vice unique to Richard in this period and he was still able to create a capable government.Kings, Contrasts, and Nostalgia for Better DaysRichards effigy over his tomb in Fontevraud Abbey in Anjou. Source: Wikimedia CommonsRichards administration ruled very successfully during his absences and was dismantled by John before Richard returned and restored it again. This last part is perhaps the best indicator as to why Richard became so beloved after his death.In contrast to Richards sanctified image as the paragon of kingly virtue, John, after he succeeded Richard, is remembered as arguably one of Englands worst kings. He was a tyrant who abused his subjects and financially and politically drove the Angevin Empire into the ground. Worst of all perhaps, John lost almost all his French territoriesbuilt up by his family over generationsin less than a decade.Small wonder then, that Richard was so fondly remembered compared to what came after. The zenith of the Angevins was immediately replaced by its nadir. Richard may have just maintained the status quo as king after his father, but this was enough to make him bring more prestige and glory to England than John.King John, From Cassels History of England, 1902. Source: Wikimedia CommonsYet it wasnt just in terms of glory that Johns failures raised Richard. Johns tyranny and administrative incompetence make Richard seem the more just and noble king. It is not that Richard was even that truly just and moral a king, but he maintained a degree of civil harmony that his brother did not during his reign or in his rebellion. Indeed, the idea of Richard restoring justice to England over Johns tyranny would become a staple of English folklore after his death in the classic tale of Robin Hood.In essence, Richard may not have been the best ruler, nor spent much time in England. Yet, his glamor and charisma, combined with the stability of his reign on a domestic level, is what made him loved in England. He was the last shining beacon of Englands high medieval Angevin glory before it fell apart. Had he lived longer, he might have become a great king residing in England, or he might not havethat question must be left to speculation.0 Comentários 0 Compartilhamentos 115 Visualizações

WWW.THECOLLECTOR.COMHow Did Richard the Lionheart Become Englands Most Famous King?Richard I (1157-1199), the Lionheart, is celebrated as Englands great warrior king, a man who embodied the ideals of medieval chivalry and nobility. Historically, however, Richard was notorious for having had little interest in England or the Englishand in truth, he was never supposed to rule England at all. Yet despite this, he is still beloved as an English national icon and one of the countrys most beloved rulers. How then did Richard become King, and why is he so beloved in a country he apparently cared little for?Born to Rule, but Not in EnglandThe iconic statue of Richard I outside the Houses of Parliament in London. Source: Wikimedia CommonsRichards re-appraisal as a very un-English king is already well known. All told, he only spent six months in England and spent almost all his reign abroad on Crusade and other ventures that nearly bankrupted the country. So how did such an un-English man become king of England? To understand that we must look back at his family and origins.Born, interestingly enough, in Oxford, Richard was the third oldest child and second to survive infancy, of Henry II of England and Eleanor, Duchess of Aquitaine. His parents were the ultimate medieval power couple. Between them, they ruled over a vast dominion known as the Angevin Empire, which included England and much of modern-day France, Wales, Ireland, and Scotland. Richards father was an energetic and ambitious king, and his mother was a brilliant political operator and famous cultural patron.Richard spent his early years between England and his parents French territories receiving a courtly education. Far from the military meathead as he is sometimes portrayed, Richard was a cultured prince who even wrote poetry, literacy being a notable gift at the time. He spoke both Court French and Occitan (his mothers first language) but it is unknown if he ever spoke English.Richard was groomed to be an ideal medieval ruler, but not of England, which was to be inherited by his older brother, Henry. Instead, Richard was to inherit his mothers Duchy of Aquitaine. In other words, Richard was born not to be King of England but an Anglo-Norman French duke. By the late 1160s, Richard was immersed in the famous cultural court of his mothers Aquitanian estates, his future seemingly pointed very much away from England.Duke of AquitaineLouis VII of France, 1375-80. Source: BnFIn 1167, Richard pledged homage as future Duke of Aquitaine to King Louis VII of France. In practice, Richard was of course subservient to his father, though Henry was technically also a vassal of Louis due to his French and Norman holdings. The complex legal framework of feudal vassalage aside, Richard was soon given more practical responsibilities.In 1171 Henry II decided his sons should prepare for their succession. His first son was elevated to co-monarch, becoming known as Henry the Young King to ease confusion. Meanwhile, Richard was officially made Duke of Aquitaine at the tender age of 14. Although Eleanor still had a hand in governance, Richard undertook important duties while gaining ruling work experience.However, in 1173 Henry the Young King rebelled against his father for taking the revenue earned by the Young Kings new positions for himself. Richard joined his brother, supported by their mother, who had all but legally separated from Henry II due to infidelity, alongside his Aquitanian vassals and with King Louis also providing support. Barely 15 years old, Richard was now a military commander in this family squabble-turned-international conflict.Henry II, 1523 portrait. Source: Wikimedia CommonsDespite his youth, Richard showed an impressive aptitude for warfare, but in 1174 Henry II made a separate peace with Louis, and then captured Eleanor, forcing the brothers to capitulate. Their father forgave them but kept their mother in custody, to ensure continued compliance. Henry did, however, make one demand of his second son, ordering Richard to pacify the Aquitanian lords who were still in rebellion.Whether or not Richard felt any qualms about betraying the subjects who had previously supported him, he still dutifully obeyed his father. Richards military reputation continued to grow as a tactician and warrior, and soon he gained his magnificent epithet: Cur de Lion, or the Lionheart, for his bravery and skill.However, Richards lack of enthusiasm led to a weak pacification policy of all sticks and no carrots. As a result, he faced repeated Aquitanian uprisings from 1175 to the early 1180s. He also faced threats from Frances new king Philippe II and even his brothers Henry and Geoffrey of Brittany, though his father did his best to mediate these conflicts.Warrior Duke to Unintended HeirDetail of a miniature of Richard I doing homage to Philippe for Normandy, 12th-13th century. Source: PicrylRichards life was one of constant diplomatic, political, and military maneuvering as he struggled to assert himself in the violent world of the medieval elite. Yet he seemed more than up to the task and may well have become a powerful and respected French-Aquitanian Duke. Then, in 1183, the Young King died suddenly of typhus and Richards life, not to mention the fate of the Angevin Empire, was turned upside down.Richard was now heir to the throne, with all the responsibilities that came with it. Though he had likely returned to England on occasion, his main focus had been on Aquitaine. He had spent his whole life so far learning to be a French duke but was now to become a king. The two certainly had transferable skills but a provincial vassal was on a very different level to being the sole ruler of a vast multinational dominion. Furthermore, to rebalance his empire, Henry II demanded Richard to hand over Aquitaine to his younger brother John. Richard refused to even consider it, even after Henry released Eleanor to negotiate the handover with him.Some have seen Richards refusal as a sign that he would have preferred to keep Aquitaine than take the English crown. However, after spending all his life preparing to rule Aquitaine, and almost a decade fighting over it, Richards refusal is understandable. Strategically, it was also a vital asset and a strong powerbase for Richard, which his brother could use to challenge him in the future.The Angevin Empire in 1154. Source: Wikimedia CommonsFor four years, Richard stubbornly refused to give up Aquitaine, his defiance teetering dangerously close to open rebellion. In 1187, things escalated dramatically when Richard signed up for the newly called Third Crusade as penance for the brutality of his previous actions against his Aquitanian vassals. Henry II refused to let Richard risk his life in the Holy Land and moved from diplomatic pressure to outright force.However, Richard was well-liked by Henrys other vassals, and many sided with him, the worst betrayal being when John, Henrys favorite son, took his brothers side. Henry even went so far as to ask Philippe II of France to assist him. However, in a display of his budding political abilities, Richard managed to secure Philippe as his ally instead. In 1189, Richard and Philippe defeated Henry at the Battle of Ballans and two days later Henry died, it was claimed, of a broken heart.Absent Ruler of an EmpireRichard I, by Merry-Joseph Blondel, 19th century. Source: Wikimedia CommonsSo that is how Richard, the second son of a king and destined all his life to be a French duke, suddenly found himself king of England. Or more accurately, ruler of the Angevin Empire. Though the king of England was his senior title, Richards dominion was far more than just England. Westminster may have been his capital, but Rouen, Chinon, Poitiers, and Limoges were all major centers of governance and administration.So how did Richard fare as a ruler? Notoriously, barely a year after his coronation, Richard left his kingdom to go on Crusade, not exactly the most responsible action for a fledgling king. However, Richard had signed up for the Crusade before becoming king, and backing out would have been a terrible loss of face. Nor was he the only major European ruler to go, both Philippe of France and the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa had also taken the cross. In fact, going on Crusade was a powerful display of Richards power and his dominions prestige.Yet Richards crusading venture had mixed results. Militarily, he won several victories and famously went toe-to-toe with the legendary Saladin. However, he fell out with Philippe and the Duke of Austria, who commanded the Holy Roman Empires contingent after Barbarossa died. As a result, they both abandoned the Crusade, forcing Richard to make peace with Saladin and give up on his dream of taking Jerusalem. Yet on return from the Crusade, things only got worse.Saladin, made in Paris, 1584. Source: The British MuseumWhile heading home, in autumn 1193, Richard was blown off course and had to travel through Austria. However, he was recognized and kidnapped by the Duke of Austria, who then sold him to the new Holy Roman Emperor, Henry VI, who demanded a ransom of 150,000 marks, more than twice the annual royal revenue. After several months the money was finally raised through a one-off tax and Richard returned to his kingdom in early 1194only to find it a total mess.After hearing news of Richards capture, John made a bid for the throne, while a newly returned King Philippe attacked Richards French territory. Normandy and Anjou were in serious jeopardy, Aquitaine was again in rebellion and mercenaries in Johns pay had taken control of several parts of England. It was a small miracle that his mother and the administration ruling in Richards absence were even able to raise the funds to secure his release.A Reign Cut ShortThe remains of Chteau Gaillard in France, an imposing castle built by Richard, who may have also been its chief architect as well. Source: Wikimedia CommonsRichard returned to a financially drained and politically unstable kingdom. Thankfully on his triumphal return to England, Johns attempted coup collapsed almost immediately. After the last of his mercenary forces were scoured from their strongholds, Richard magnanimously forgave his brother. With England put to rights, Richard swiftly moved to France to deal with Philippe.Richard managed to militarily and diplomatically outfox Philippe, forming a coalition of other powerful lords, such as the Duke of Flanders, to assist him as he defeated Philippe in a series of brilliant campaigns to retake his lost territory. Richard even found the time to design and construct the Chteau Gaillard, a state-of-the-art fortress that dominated the Seine Valley and controlled the frontier with France.On the eve of the 12th century, Richards rejuvenated Angevin Empire was the undisputed great power of Western Europe. However, in March 1199, as Richard was besieging Chteau de Chlus-Chabrol, the home of yet another rebellious Aquitanian lord, he was hit in the shoulder by a speculative crossbow bolt from the castle walls. The wound became infected and three days later, Richard died in his mothers arms. So, he passed at 42, his life cut short in its primebut then again Richard, always the warrior king, had lived by the sword.Richard the Lionheart Statue at Fecamp Abbey, France. Source: Wikimedia CommonsFor most of his adult life, Richard had been engaged in business outside of England and famously he spent very little of his decade-long reign in England itself. Yet at the time of his death, he was a well-loved king and despite historiographical pushback, English infatuation with him has only grown. His motto Dieu et mon Droit (God and my Right) is still the motto of the Royal Family, and his coat of arms of three lions, a national symbol of England. Why does England love the king who shouldnt have been? More pertinently, was he as great a king as popularly believed?Historian Stephen Runciman described Richard as a bad son and a bad king, but a gallant and splendid soldier. Yet there is much to be considered in appraising Richards actual rule.The Glamor of the Warrior KingThe three lions had been a symbol of the previous Norman Kings of England, but Richard was the first to use this stylization. Source: Wikimedia CommonsIn one regard at least, the adoration of Richard is understandablehe was an astonishingly glamorous king. Richard was the avatar of medieval chivalry, embodying all the traits popularized by troubadours and romantic poets of the time. There are accounts critical of his behavior but many of these were sponsored by his enemies and even they often acknowledge Richards splendor. By most accounts, he was good-looking, eloquent, and a generous lord, though prone to thoughtlessness and vanity at times.He was not only a brilliant general and warrior but was dedicated to his troops and often put himself in danger for their safety. While he did commit acts of brutality, they were not the exception for the time and by and large, Richard was famous for being courteous to his enemies on and off the field. Famously, he even forgave the arbalest who shot him while on his deathbed. Though Richard spent little time in England, his military glory, especially the Crusade, greatly boosted contemporary English prestige.Richard the lionheart, floortile, 1250s. Source: British MuseumRegarding the little time he spent in England, it must be remembered that his domain included far more than just England. Richards absence from England does not mean an absence of kingly qualities. The fact is, however, Richard died without doing much actual ruling because wars, of his own creation or not, dominated his reign.Yet, Richards military career and charisma do not mean he was a capable ruler. In his time as king, he spent the royal treasury rather than saved its coin, but the kingdom was prosperous enough to recover even from the extra taxes levied to pay his ransom, though many Church chroniclers criticized him fiercely for levying taxes on the Church to repay this debt. He was certainly not the great statesman and reformer his father had been. However, he was not a tyrant or political failure. He did sell offices of state to the highest bidder, but this was not a vice unique to Richard in this period and he was still able to create a capable government.Kings, Contrasts, and Nostalgia for Better DaysRichards effigy over his tomb in Fontevraud Abbey in Anjou. Source: Wikimedia CommonsRichards administration ruled very successfully during his absences and was dismantled by John before Richard returned and restored it again. This last part is perhaps the best indicator as to why Richard became so beloved after his death.In contrast to Richards sanctified image as the paragon of kingly virtue, John, after he succeeded Richard, is remembered as arguably one of Englands worst kings. He was a tyrant who abused his subjects and financially and politically drove the Angevin Empire into the ground. Worst of all perhaps, John lost almost all his French territoriesbuilt up by his family over generationsin less than a decade.Small wonder then, that Richard was so fondly remembered compared to what came after. The zenith of the Angevins was immediately replaced by its nadir. Richard may have just maintained the status quo as king after his father, but this was enough to make him bring more prestige and glory to England than John.King John, From Cassels History of England, 1902. Source: Wikimedia CommonsYet it wasnt just in terms of glory that Johns failures raised Richard. Johns tyranny and administrative incompetence make Richard seem the more just and noble king. It is not that Richard was even that truly just and moral a king, but he maintained a degree of civil harmony that his brother did not during his reign or in his rebellion. Indeed, the idea of Richard restoring justice to England over Johns tyranny would become a staple of English folklore after his death in the classic tale of Robin Hood.In essence, Richard may not have been the best ruler, nor spent much time in England. Yet, his glamor and charisma, combined with the stability of his reign on a domestic level, is what made him loved in England. He was the last shining beacon of Englands high medieval Angevin glory before it fell apart. Had he lived longer, he might have become a great king residing in England, or he might not havethat question must be left to speculation.0 Comentários 0 Compartilhamentos 115 Visualizações -

WWW.THECOLLECTOR.COMStories from WWII Croatia (Ustasha-era)The Independent State of Croatia, founded in 1941, did not have the same impact on Europes demographics that Nazi Germany did. Nonetheless, the brutality of the genocidal campaign it conducted against its Serbs, Roma, and Jews is haunting. Its history and the memory thereof also contain lessons regarding the mechanics of genocide, terror, and commemoration.Read on to discover the little-known Independent State of Croatia and its genocidal campaigns, starting with the localized form of fascist ideology adopted by it, the states implementation of genocide, in addition to some of the questions surrounding the memory of that genocide.An Exercise in Contradiction: Fascism in Croatias IdeologyPhotograph of a forced conversion of Serbs in Glina, 1941. Source: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington DCThe proponents of fascism in Croatia harbored particular hatred for the Serbs, who they saw as traitors to the Catholic Church. This is one of the factors that sets Croatian fascism and the Ustasha, the fascist party, apart from other Axis ideologies, particularly German and Italian fascism. Additionally, the Ustashas leader and dictator of the Independent State of Croatia, Ante Paveli, saw the Serbs existence within Croatia as a threat to Croat culture. He believed the Serbs were products of Slav propaganda and were engaged in an effort to take over Croatian society for centuries.In defining the ideology for their genocide, the ministers of the Independent State (NDH) had to walk an especially thin tightrope. There was and still is no such thing as a pure Croat; Serbs, Bosniaks, Croats, Slovenes, Montegrins, Jews, and Roma had mixed and integrated for centuries. The only effective ways to define being a pure Croat were extreme Catholic fundamentalism and claiming that Croats descended from a Germanic people.This vision of racial purity contained a bizarre contradiction; it included Bosniaks, who were Muslim because Paveli believed they were merely Croats who converted to Islam under the Ottomans to preserve Croatian culture (Adriano, Cingolani, and Vargiu, 2018, p. 191).The Ustasha recruited Croat Catholic priests to supervise conversions, arrests, and even massacres. With the NDHs encouragement, priests who had lived alongside Jews, Roma, and Serbs for years turned on neighbors and friends.Surely Some Revelation Is at HandSerbian Children wearing Ustasha Uniforms assembled at Stara Gradiska Concentration Camp. Source: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington DCOn April 30, 1941, the NDH stripped all Orthodox Christians of citizenship, banned the use of the Cyrillic alphabet, shut down all Orthodox Christian institutions, and banned the term Serbian Orthodox faith. Anyone who could not prove sufficient aryan Croat heritage had to wear an armband.The Ustasha state made its attitude toward Jews even clearer when its ministers announced Pavelis state intended to pursue a similar policy to Nazi Germany. The state required them to wear yellow discs with the Croatian letterwhich stood for idov, or Jew (McCormick, 72).To terrorize Serbs, Jews, and Roma into conversion, Ustasha soldiers raided homes in Lika (Glenny, 486-9). These thugs emptied Serbian and Jewish homes at night, forcing families and people to arrange their affairs and belongings in mere minutes before dragging them away to extermination camps, the first of which, Koprivnica, opened in May 1941.By the end of May 1941, Koprivnica held 3,000 Serb Prisoners.In June, Paveli and Budak ordered the creation of three more camps two on Pag island in Slana, a camp for men, and Metanja, a camp for women, and one in Jadovno, a mountain town in the Velebit range.In August 1941, when Italian soldiers took over Pag, they found 791 bodies and an officer wrote in a report:upper and lower limbs were tied in the case of almost all male corpses. [] [L]ethal wounds to the chest, back, and neck produced by bladed weapons were verified on most corpses. The pits had been covered hastily with dirt and rocks, before all the victims had died, as proven by the tragic expressions on the faces of most corpses (Adriano, Cingolani, and Vargiu, 192).The Pag camps, however, were only a small ripple in a wave of violence compared to Jasenovac.Jasenovac: The Symbol of an Ongoing Information WarPhoto of an arriving inmate being forced to remove a ring at Jasenovac, unknown year. Source: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington DCThe facts surrounding the Jasenovac concentration camp and its related genocide are intensely debated today, with Serbian politicians exaggerating the statistics or Croatian politicians, such as former president Franjo Tudjman himself, understating them. The problem with debunking claims on either side, however, is that few objective statistics exist to define a concrete number of state-sanctioned murder victims from 1941 to 1945.Jasenovac opened in August 1941 and consisted of five camps on the border of Bosnia and Croatia. Jasenovac I and II shut down in November 1941 after the Ustasha executed all their Jewish, Serb, and Roma inmates because they lacked the extremist manpower to operate all five camps at once. Jasenovac III housed Balkan Jews, Roma, and Sinti before shipping them to extinction at Auschwitz. Jasenovac IV and V housed mostly Serb and Croat political dissidents.Jasenovac initially occupied 60 square miles of territory. By 1945, it had expanded to 130 square miles, which is roughly the size of Atlanta or Las Vegas.Wretched cattle cars full of hungry, tired Serb, Jewish, and Roma people made their way to Jasenovac in August 1941.Arriving prisoners of Jasenovac stripped of their belongings. Source: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington DCThe prisoners arrived at a camp built to house 7,000 people, but it never reached that capacity because people died so quickly. If they made it past the gates, they found the stench of overflowing latrine pits, unwashed bodies, blood, and decay overwhelmed all prisoners who stepped off the cattle cars.Occasionally, smokes scent came from the chimneys, and ashes landed on the dirt next to the rails and barracks. These ashes came from the camp crematorium, where the Ustasha thugs shoved living people into the furnace at a camp brick factory. Once processed and sentenced by the arbitrary and often bloodthirsty camp staff, one received a bowl and thin clothes; that is, if one was fit to work.Food typically consisted of hot water flavored with cabbage leaves. Prisoners ate grass and leaves, and in some cases, the corpses of dead animals, desperately clinging to life through anything edible they could find. Guards forbade Serb prisoners from any drinkable water. They would have to drink from the Sava River, whose once-pristine teal waters contained latrine pit waste and decomposing bodies.Prisoners forced to labor at Jasenovac. Source: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington DCWork itself often killed prisoners, as construction, agriculture, brick, and blacksmith work often put these tired, weary people in dangerous situations with no safeguards. Prisoners burned to death, fell off buildings, or collapsed under the weight of heavy objects.By October 1941, starvation began killing the prisoners. Day by day, they struggled to find food, some even descending to looking through feces in the latrine pits for undigested beans or cabbage leaves.Barracks were not suitable for survival either. They were hastily constructed and had several gaps in their walls and roofs, gaps that water and snow seeped through in the winter. A long list of painful, long-suffering diseasesTyphoid, typhus, malaria, diphtheria, and even the flukilled thousands of prisoners, whose bodies would be left to rot and worsen the conditions for the surviving prisoners.There were eight barracks; prisoners lived in six of them. The last two were the infirmary and the clinic. If one were sent there, it likely meant no one would ever see them alive again.Serbian Prisoners at Jasenovac. Source: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington DCGuards and staff at these two barracks would either wait for prisoners to die or, starting in 1942, take a group of dying inmates to the brick ovens, where people were cremated alive to make space for more prisoners.This was not the only way the Ustasha cleared the way for more inmates in Jasenovac. In the nearby area of Gradina, the Ustasha fenced off a patch of land specifically for prisoner liquidation. The Ustasha rounded up Roma and Sinti prisoners and marched them to this killing field to massacre them.After August 1942, seeing Nazi Germanys zeal for executing Jewish people, the Ustasha decided they would begin sending Jews to Auschwitz. In just one year at the single camp of Jasenovac, the Ustasha had eliminated anywhere from 8,000 to 25,000 Jews, which at the time constituted about two-thirds of Croatias Jewish population. The remainder would be Nazi Germanys undertaking. The Ustasha guards could then focus on greater Croatias Roma, Sinti, and most importantly, its Serbs.They did so until April 1945. In the process, this camp likely murdered about 100,000 people: almost 50,000 Serbs, about 20,000 Roma and Scinti, 13,000 Jews, 4,000 Croats, and 1,000 Bosniaks.The facts grow more disturbing looking closer at the demographics. Over 50,000 of these estimated 100,000 victims at this one concentration camp were women and children. During its operation, Jasenovac hosted over 50 mass graves, many of which were not even exhumed or discovered until decades later.AftermathRuins of the Village of Jasenovac, 1945. Source: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington DCAcross all of occupied Greater Croatia, a sum between 200,000 to half a million Serbs, Roma, Sinti, Jews, and political dissidents were murdered, over half of them being Serbs, recognized as the most populous target group in Ustasha territory. The genocide ended with the end of fascism in Croatia in the early summer of 1945. With communist partisans growing in strength, Paveli devoted his Ustasha to two things: fighting the partisans and fleeing the Balkans.A rat line was established at the Austrian border in the north with the help of priests who held Ustasha sympathies. Paveli and other higher-ups fled to Austria and then to Rome. From there, many escaped to Argentina, escaping the punishment they had dealt to countless others.As a new state, the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia rose from the ashes of the Ustasha. The people of Yugoslavia were traumatized and struggled to trust each other. Titos government, on the surface, allowed each ethnicity to assert its identity and speak its language. But the reality was more complex.Photograph of Garavice Memorial Complex, Bihac, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Source: Wikimedia CommonsMonuments such as the memorial complex in Garavice, Bosnia-Herzegovina, are overgrown today and often prompt questions from the uninitiated as to their purpose. A plaque at this particular monument, with an excerpt from Ivan Goran Kovacics Jama, reveals its purpose: commemoration of massacres by the Independent State of Croatia.Similar to Germany in the post-war period, monuments to victims were constructed. However, in Titos Yugoslavia, seldom was the Ustasha discussed in schools or institutions. Consequently, with the lack of a formal, positive effort to reconcile with history, some of the communities in the region inherited a wish to settle the score while others feared another genocide.Thus, the Jasenovac concentration camp was often evoked by Serbs in the 1990s. When Croatia declared independence, even using the same coat of arms as the Ustasha on their flag, it prompted both frightened communities and communities wishing for revenge to take up arms against the new independent Croatian statewhich demonstrates this genocides long-lasting tensions and historical effects.ReferencesAdriano, Pino, Giorgio Cingolani, and Riccardo James Vargiu. Nationalism and Terror : Ante Pavelic and Ustashe Terrorism from Fascism to the Cold War. Budapest: Central European University Press, 2018.Council of Europe. Factsheet on the Roma Genocide in Croatia. Factsheet on the Roma Genocide. Council of Europe, n.d. https://www.coe.int/en/web/roma-genocide/croatia.Glenny, Misha. The Balkans : Nationalism, War, and the Great Powers, 1804-1999. Toronto, Ontario: House of Anansi Press, 2012.Jovan, Mirkovic. OBJAVLJENI IZVORI I LITERATURA O JASENOVAKIM LOGORIMA. Jerusalim.org. Belgrade, Serbia: GrafoMark, 2000. https://web.archive.org/web/20100331232624if_/http:/www.jerusalim.org/cd/izvori/jmirkovic-izvori_2000.pdf.Lukic, Dekan. You Are Going to Lose This War. The Guardian, April 3, 1999, sec. World news. https://www.theguardian.com/world/1999/apr/03/3.McCormick, Robert B. Croatia under Ante Pavelic. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2014.Pejakovi, Ivo , Vesna Tereli, and ino ivanovi. Slana Concentration Camp 1941. Documenta: Centre for Dealing with the Past. Documenta. Accessed February 29, 2024. https://documenta.hr/en/slana-concentration-camp-1941/.Tanner, Marcus. Croatia : A Nation Forged in War. New Haven ; London: Yale Nota Bene, 2001.Traynor, Ian. Franjo Tudjman. The Guardian, December 13, 1999, sec. News. https://www.theguardian.com/news/1999/dec/13/guardianobituaries.iantraynor.United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Jasenovac. Encyclopedia.ushmm.org. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, n.d. https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/jasenovac.0 Comentários 0 Compartilhamentos 117 Visualizações