-

Ροή Δημοσιεύσεων

- ΑΝΑΚΆΛΥΨΕ

-

Σελίδες

-

Blogs

-

Forum

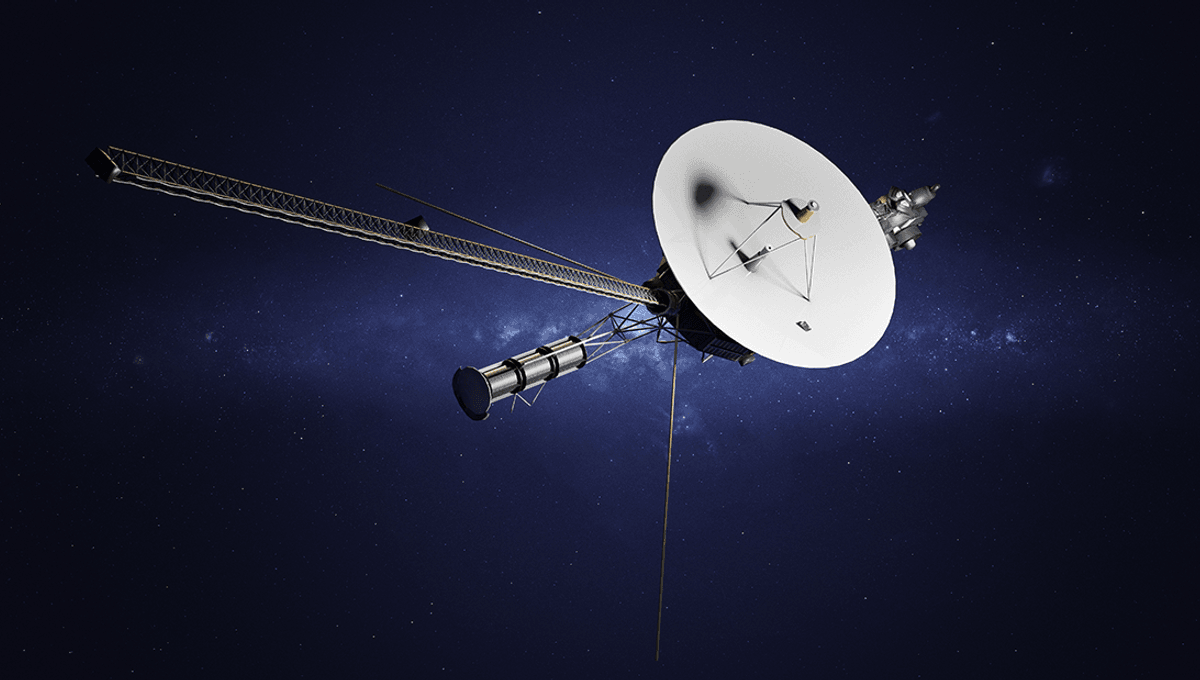

In 40,000 Years, Voyager 1 Will Have A Close Encounter With Gliese 445

In 40,000 Years, Voyager 1 Will Have A Close Encounter With Gliese 445

In 40,000 years, long after its mission is over, NASA's Voyager 1 spacecraft will have a close encounter with Gliese 445. It won't be the probe's last.

The rest of this article is behind a paywall. Please sign in or subscribe to access the full content. The Voyager probes were launched in 1977 and have been traveling ever since. At the moment, Voyager 1 is around 168 AU from the Earth, having become the first spacecraft to go beyond the heliosphere, cross the heliopause, and enter interstellar space. At its current position, it takes 23 hours, 19 minutes, and 9 seconds for signals from Earth to reach the spacecraft. At its current speed of about 61,195 kilometers per hour (38,025 miles per hour), it will still take over a year to widen that light-distance to a full 24 hours. At that point, Voyager will become the first human-made object to reach a full light-day from Earth. While Voyager's mission is nearly over, with fuel dwindling and the spacecraft expected to power down permanently in the 2030s, its journey is only just beginning. First, it will pass through the Oort cloud, the hypothetical spherical shell of objects thought to surround our Solar System, right at the edge of the Sun's influence. "The distant Oort cloud marks the gravitational edge of the Solar System, in a vast region of undiscovered objects," NASA explains of the cloud, first hypothesized by Dutch astronomer Jan Oort in 1950. "Short-period comets may originate in the scattered disk, inner, part of the Oort cloud, while long-period comets likely come from the spherical, outer portion of the Oort cloud. These comets only pass the Sun on rare occasions, possibly when disturbed by distant passing stars or galactic tides. There is speculation of other large planets in this region that may disturb comets in their vicinity, but none have yet been discovered." At the lower range of estimates, the Oort cloud could begin around 1,000 AU from the Sun. If the Oort cloud does begin here, the spacecraft could reach it in just a few centuries. However, given the sheer scale of the cloud, it will be there for tens of thousands of years. "Much of interstellar space is actually inside our Solar System," NASA explains. "It will take about 300 years for Voyager 1 to reach the inner edge of the Oort Cloud and possibly about 30,000 years to fly beyond it." Assuming that the Voyager probes make it through the cloud undamaged (a likely outcome, given that space is not the asteroid-dodging exercise sci-fi would have us believe), they could go on relatively unscathed for many, many years beyond that. For a long time, Voyager will not be near any astronomical objects, drifting on its own through the cosmos, far from sources of heat and light. But in 40,000 years, it will get a brief close encounter with another star, coming closer to it than home. "It took 35 years to reach interstellar space, but it will take 40,000 years for Voyager 1 to be closer to the star AC +79 3888 than our sun," NASA explains. "Alpha Centauri is the closest star to our own right now, but because stars are moving, Voyager 1 will actually get within 1.7 light years of AC +79 3888 (aka Gliese 445) in 40,000 years." A paper examining the future stellar flybys of probes on an escape velocity from the Solar System puts the figure at more like 44,000 years. Gliese 445 is an M-type main-sequence star with around a third of the mass of our Sun. At the moment ,it is around 17,000 light-years from Earth, but by the time the encounter with Voyager happens it will be around 3.5 light-years away from us. It will not be the spacecraft's final encounter with another star. "Statistically, a spacecraft will encounter stars within a given distance at approximately the same rate as the Sun does, which Bailer-Jones et al. (2018b) inferred to be one star within 1 pc every 50 kyr," the study explains, adding that more-distant encounters are difficult to predict due to uncertainty in the data. "This rate scales quadratically with encounter distance (i.e. one star within 0.1 pc every 5 Myr). As the spacecraft are not leaving the Galaxy, it is inevitable that the spacecraft will pass much closer to some stars on longer timescales." Nevertheless, the team was able to predict the closest approach that Voyager will have in the not-too-distant future, astronomically speaking. They found that the spacecraft will encounter TYC 3135-52-1, a main-sequence star, in around 303,000 years. At this point, it will be around 0.965 light-years from the star, so still quite wide of it. Looking at the data, it is unlikely Voyager 1 will be captured by a star any time soon, and will continue to drift through the cosmos with only the Golden Records for company. "The timescale for the collision of a spacecraft with a star is of order 1020 years," the team concludes, "so the spacecraft have a long future ahead of them." The study has been posted to the pre-print server arXiv.