-

Новости

- ИССЛЕДОВАТЬ

-

Страницы

-

Статьи пользователей

-

Форумы

How To Park A Dangerous Asteroid So It Doesn’t Bite You Later

How To Park A Dangerous Asteroid So It Doesn’t Bite You Later

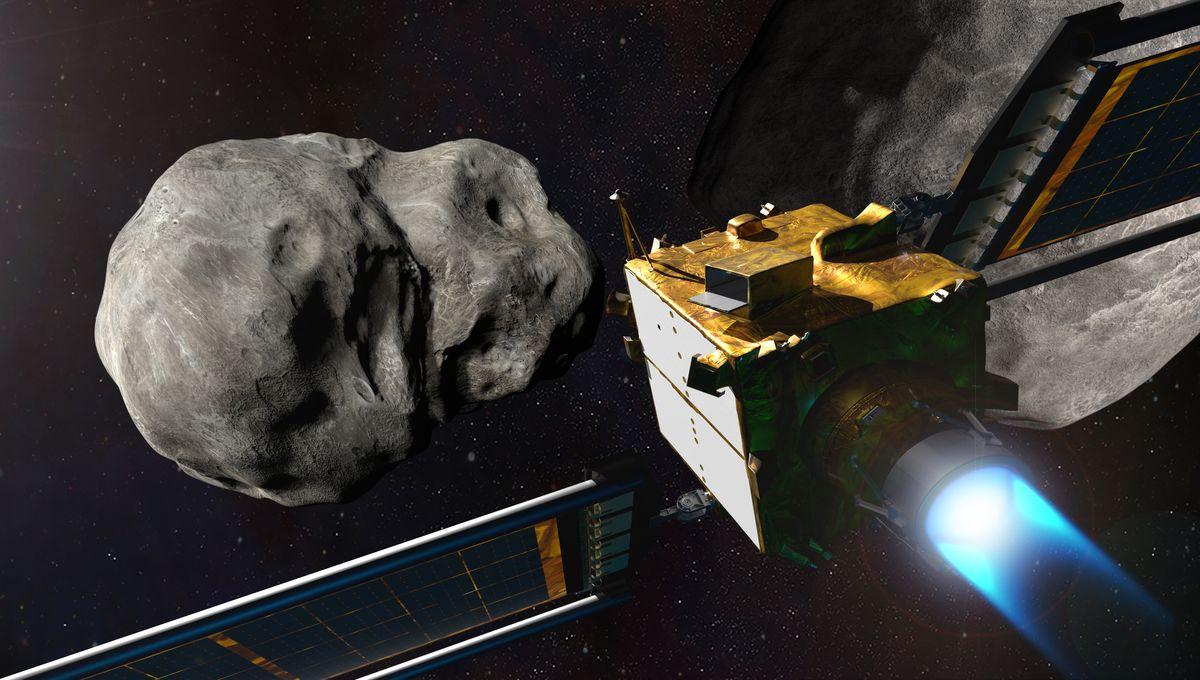

A planetary science conference has heard how to redirect threatening asteroids so they don’t come back and endanger the Earth at a later date. You’d think that would be a key feature of any mission to protect the planet, but that assumes the mission is run by scientists, not chief financial officers.

The rest of this article is behind a paywall. Please sign in or subscribe to access the full content. When Hollywood imagines an incoming object threatening to destroy civilization, if not all life on Earth, they usually envisage blowing it up with nuclear bombs. Most scientists dedicated to the task take a less photogenic approach, getting there early and nudging the threat enough to change its path to take it past the Earth. The DART mission proved this could be done by slamming a spacecraft into the threat, although even less dramatic ideas remain under consideration. There’s one way in which the filmmakers might be right besides putting on an epic show. If you blow the threat up, you only ever have to worry about fragments, whose effects would be more local than global. Redirect the object in question, and it will still be in an orbit close to Earth, and could hit not too much later. If you’re confident our space program will keep advancing, then by the time the object’s a threat again it might be easier to deal with, but setbacks could change that calculation. Messing up badly enough could leave us with a shorter warning time to launch another redirection mission. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign PhD student Rahil Makadia is one of those who doesn’t want to make a problem that resurfaces zombie-like. He noted there are “gravitational keyholes” where a passage moderately close to Earth can change an asteroid’s orbit so that it becomes a threat again in future. "Even if we intentionally push an asteroid away from Earth with a space mission, we must make sure it doesn't drift into one of these keyholes afterwards. Otherwise, we'd be facing the same impact threat again down the line," Makadia said in a statement. As Makadia and co-authors noted, if we hit the right spot on an asteroid, this shouldn’t be a problem. We can park it in an orbit that misses both Earth and keyholes for a very long time to come. Identifying that spot, however, isn’t easy, and Makadia’s team are developing the tools to ensure we have the capacity when the need arises. Using the DART mission’s findings, they have made probability maps for how hits at different locations would have shifted shift Bennu, one of the potentially hazardous objects we know best, in 2014. Crosshairs in the above video indicate the best places to hit to avoid gravitational keyholes. The authors note that varying compositions, shapes, and even spin rates mean every object will be unique, requiring its own pre-hit assessment. When we have plenty of time before a potential impact, a spacecraft could map it extensively before the spot is chosen, but that may not always be an option. “Fortunately, this entire analysis, at least at a preliminary level, is possible using ground-based observations alone, although a rendezvous mission is preferred,” Makadia said. "With these probability maps, we can push asteroids away while preventing them from returning on an impact trajectory, protecting the Earth in the long run.” Still, you just know there’s going to be someone arguing that all this is too expensive and we should just knock the planet’s potential doom far enough off course that it’s safe within their financial timetable or electoral cycle. The work was presented at the EuroPLANET Conference in Helsinki, with an extended abstract available online.