-

Ροή Δημοσιεύσεων

- ΑΝΑΚΆΛΥΨΕ

-

Σελίδες

-

Blogs

-

Forum

Why Is It So Difficult To Find New Moons In The Solar System?

Why Is It So Difficult To Find New Moons In The Solar System?

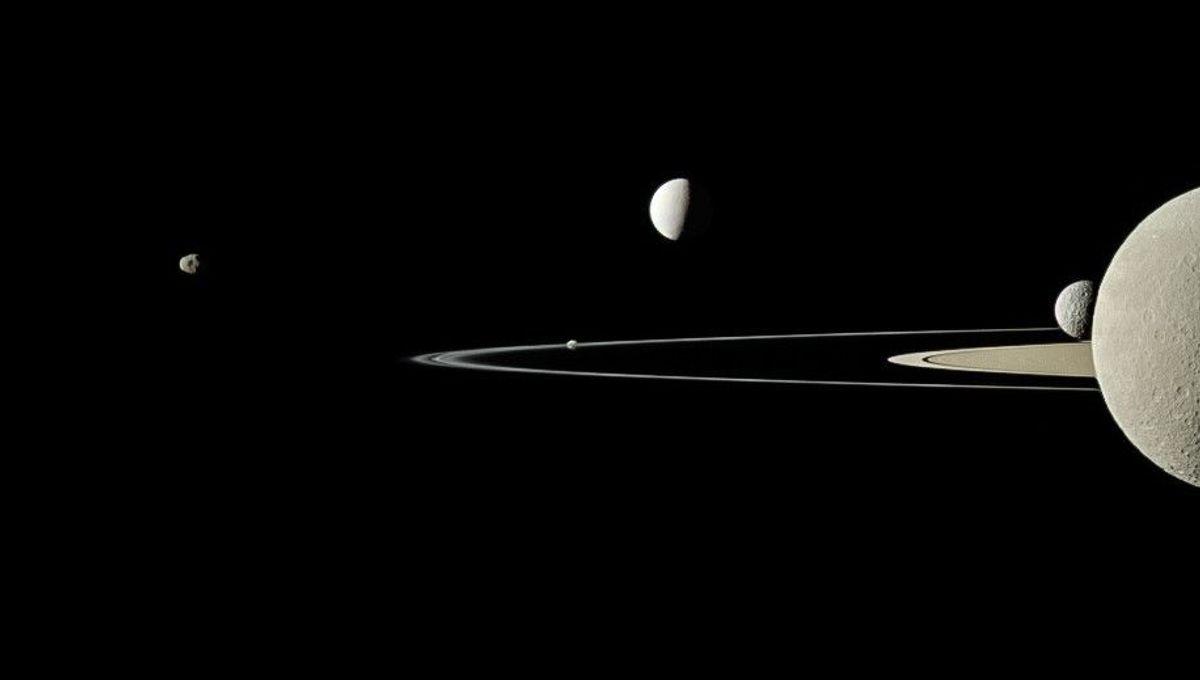

With the announcement of a new moon around planet Uranus, it came to our attention that some people are shocked to find out that we do not know exactly how many moons are around the planets that exist in the Solar System. Finding moons nowadays is a lot more challenging than you might think.

The rest of this article is behind a paywall. Please sign in or subscribe to access the full content. Mercury has no moon, and neither does Venus (although it has a quasi-moon named Zoozve). Earth has the Moon, capital M. Mars has Phobos and Deimos. Then things get a bit complicated. As of the latest count, Jupiter has 97 moons. Saturn now has 274, after a whopping 128 moons were discovered in a single swoop. Uranus has 29 moons, the latest one only just announced, and Neptune closes the planetary parade with 16 confirmed moons. The Solar System has a total of 419 known moons around planets. If we count dwarf planets, asteroids, and other worlds, the count more than doubles. The "known" in known moon is the important part, however. It is certain that the number will grow, but we do not know when the counter will get updated. Finding moons is difficult, but we can be certain that there is no large moon hiding from view. Jupiter hasn’t got another Ganymede stashed somewhere, and there is no second Titan yet to be discovered orbiting Saturn. What is left to be discovered are small moons; you are looking at objects that are as big as a town and billions of kilometers from Earth. When the 28th moon of Uranus was discovered last year, together with the 15th and 16th moons of Neptune, the team was confident to say that there shouldn’t be any new moons that exist that are larger than 8 kilometers (4.98 miles) for Uranus and 14 kilometers (8.7 miles) for Neptune. The new moon found around Uranus is slightly larger than that limit, but it is orbiting inside the orbits of the larger moons of the planet, a location that might have been discounted as covered and completed in the past. For Jupiter and Saturn, the limit is much lower, with 2 and 3 kilometers (1.2 and 1.8 miles) as the largest possible new moons yet to be discovered, and given how the big haul of new moons from Saturn comes from a possible catastrophic collision that produced all these satellites, it is likely that more will be discovered. Size is a big deal because the smaller they are, the dimmer they appear. It is also the timing of the observations. Some of these moons orbit far away from their planets, so they take a long time to go around. Astronomers might spot them, but they might require months or years of observations to confirm they are indeed moons of that particular planet. Consider that S/2002 N5, the 15th moon of Neptune, was lost for 22 years. It goes around the planet every 9 years. As is the case with the new moon of Uranus, being too close also made life difficult, since the planet is a lot brighter than a 10-kilometer (6.2-mile) moon. And when it comes to orbits, it also matters how it goes around the planet. The orientation might not always be favorable for spotting. The orbit might also be irregular, like those that move in retrograde motion. A lot of these satellites are captured objects from the rest of the Solar System. In the centuries since Galileo Galilei found the four largest satellites of Jupiter, astronomers have found all the easy moons to spot, and now they are working through the difficult ones. Moons that are very small, not very bright, on weird and long orbits. It is not a question of a quick glance. Finding moons is a painstaking job and a long-term commitment.