-

Ροή Δημοσιεύσεων

- ΑΝΑΚΆΛΥΨΕ

-

Σελίδες

-

Blogs

-

Forum

Earendel: The Most Distant Star Ever Seen Might Not Be What We Thought

Earendel: The Most Distant Star Ever Seen Might Not Be What We Thought

Back in 2022, the Hubble space telescope appeared to have found the most distant star ever discovered. Named Earendel – morning or rising star in old English – a new paper suggests it might not be what we thought.

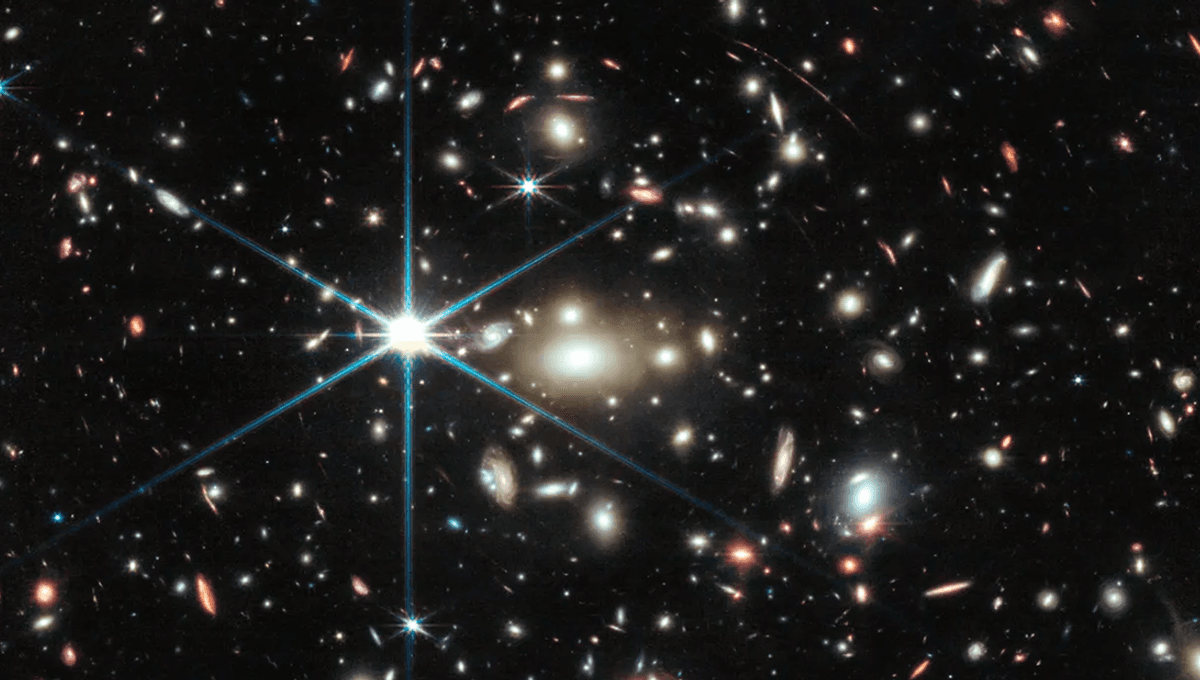

The rest of this article is behind a paywall. Please sign in or subscribe to access the full content. Earendel was spotted by Hubble due to a fortunate case of gravitational lensing, where light from a distant source has its path bent by a massive object in the foreground. In this case, light was bent around the star cluster WHL0137-08, allowing us to see Earendel an astonishing 28 billion light-years away (though it was closer to us when the light was emitted). According to analyses of these observations and subsequent observations from JWST, the light we see from Earendel was emitted 13 billion years ago. “It’s the most distant star that has been discovered thus far, which is very exciting just for the superlative of it,” Brian Welch, a member of the discovery team, told IFLScience following the discovery. “It’s also within the first billion years of the Universe so at a time when we know that galaxies look very different and we expect that stars would look very different as well.” ⓘ IFLScience is not responsible for content shared from external sites. Initial observations of Earendel suggested it was a star around 50 times more massive than our Sun. While seeing an individual star at these distances would be awesome, from the start, there were suggestions that what we were seeing was actually a binary pair. This would still be an incredible find, helping to tell us about star formation in the first billion years of the universe, which we expect to be quite different from today's cosmos. Astronomy is complex and involves a lot of uncertainties, especially at these distances. In a new paper, which uses stellar population modeling, a team suggests that what we are seeing here might not be a star or a binary star at all, but an ancient star cluster. The team looked at Earendel and other objects on the "Sunrise Arc" – the galaxy smeared out as a red arc by the gravitational lens – already thought to be a star cluster. The tiny highlighted dot is Earendel, while the central flare is from the telescope. Image credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, Cosmic Spring JWST, edited by IFLScience Comparing the sources to each other and models of stellar populations, they found that they appear to be metal-poor and similar in composition. "We find the Earendel spectrum to be highly consistent with that of an SSP [simple stellar population] across all three SSP libraries," the team explains in their paper. "We similarly see a nearly equivalent goodness of fit for image 1b, which is commonly accepted to be a star cluster. We reassuringly find that repeating the same fitting procedure for the 1a spectrum yields comparable results to 1b." Though the team does not definitively rule out a binary pair, according to their analysis, Earendel is best described as a star cluster. While we are used to surprises as we look into the distant universe, this would actually put it more in line with what our models predicted about this age of the cosmos. "What's reassuring about this work is that if Earendel really is a star cluster, it isn't unexpected!" Massimo Pascale, astronomy doctoral student at the University of California, Berkeley, and lead author of the study, told Live Science. "[This] work finds that Earendel seems fairly consistent with how we expect globular clusters we see in the local universe would have looked in the first billion years of the universe." The study is published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

.png)