An "Unknown Biogeographic Barrier" Stops Deep-Sea Jellyfish Crossing The Atlantic

There's An "Unknown Biogeographic Barrier" That Stops Some Animals Crossing The Atlantic

Deep-sea jellyfish might not have a brain, but they don’t aimlessly drift around the world’s seas. In fact, they seem to stick within their set territory with an incredible sense of order.

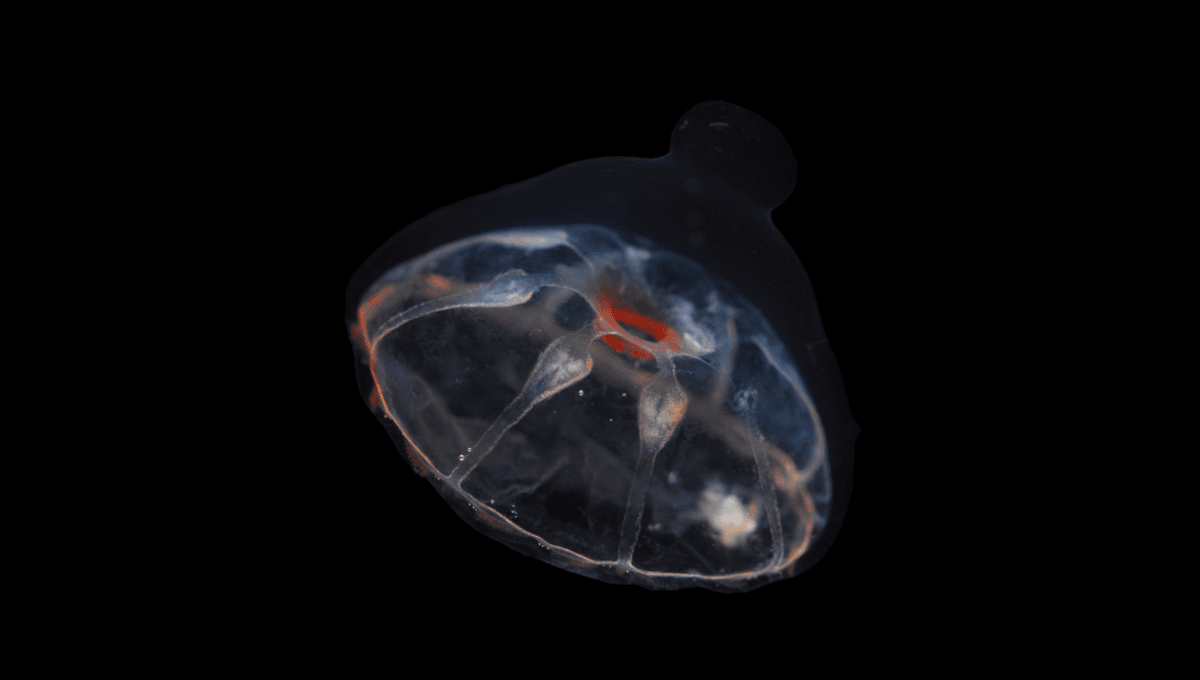

In a new study, scientists at the University of Western Australia used historical records, molecular tools, and genetic analysis to study the geographical distribution of Botrynema brucei ellinorae jellyfish in the Atlantic Ocean. While tracking their whereabouts, the researchers paid special attention to the two distinctive types of the subspecies: one with a telltale “knob” atop its bell, which is found in oceans worldwide, and another without the knob, confined to Arctic and Subarctic waters. The findings showed that the jellyfish were rigidly stuck to this regime. Knobless jellyfish never appeared south of 47°N latitude, pointing to an invisible, semi-permeable barrier in the North Atlantic Drift that seems to limit their range. “The differences in shape, despite strong genetic similarities across specimens, above and below 47 degrees north hint at the existence of an unknown deep-sea bio-geographic barrier in the Atlantic Ocean,” Dr Javier Montenegro, lead study author from the University of Western Australia’s School of Biological Sciences and the Minderoo-UWA Deep-Sea Research Centre, said in a statement. Over 120 years of data suggest that knobless jellyfish are never found below the 47°N latitude. Image credit: Montenegro et al., Deep Sea Research, 2025 (CC BY 4.0) Despite their close genetic similarity, the two jellyfish forms occupy sharply different ranges – and the “knob” appears to be the defining factor. While its function remains unknown, researchers say the contrasting distributions suggest the knob may offer the jellyfish some kind of selective advantage that allows them to tread further into the Atlantic. “It could keep specimens without a knob confined to the north while allowing the free transit of specimens with a knob further south, with the knob possibly giving a selective advantage against predators outside the Arctic and sub-Arctic regions,” Dr Montenegro said. The natural world has several other known examples of a biogeographic barrier that shapes species diversity. Perhaps the most famous is the Wallace Line that runs through modern-day Indonesia. The “invisible” line acts as a boundary between the faunal regions of Asia and Australia; to the west, you’ll find species associated with Southeast Asia like elephants, tigers, rhinos, and orangutans, but on the eastern side, you’ll find Australian species like marsupials, monotremes, and maybe the odd Komodo dragon. Much like the Wallace Line, this mysterious deep-sea divide in the Atlantic shows us that the ocean is not a continuous expanse, but a network guided by hidden boundaries and unwritten rules. Even brainless jellyfish appear to respect these invisible borders. The new study is published in the journal Deep Sea Research.