Who’s a good boy? Oosagoodboyyy?! That’s right! Your dog is a good boy! But how he got that way is a puzzle that’s long plagued archaeologists and palaeontologists.

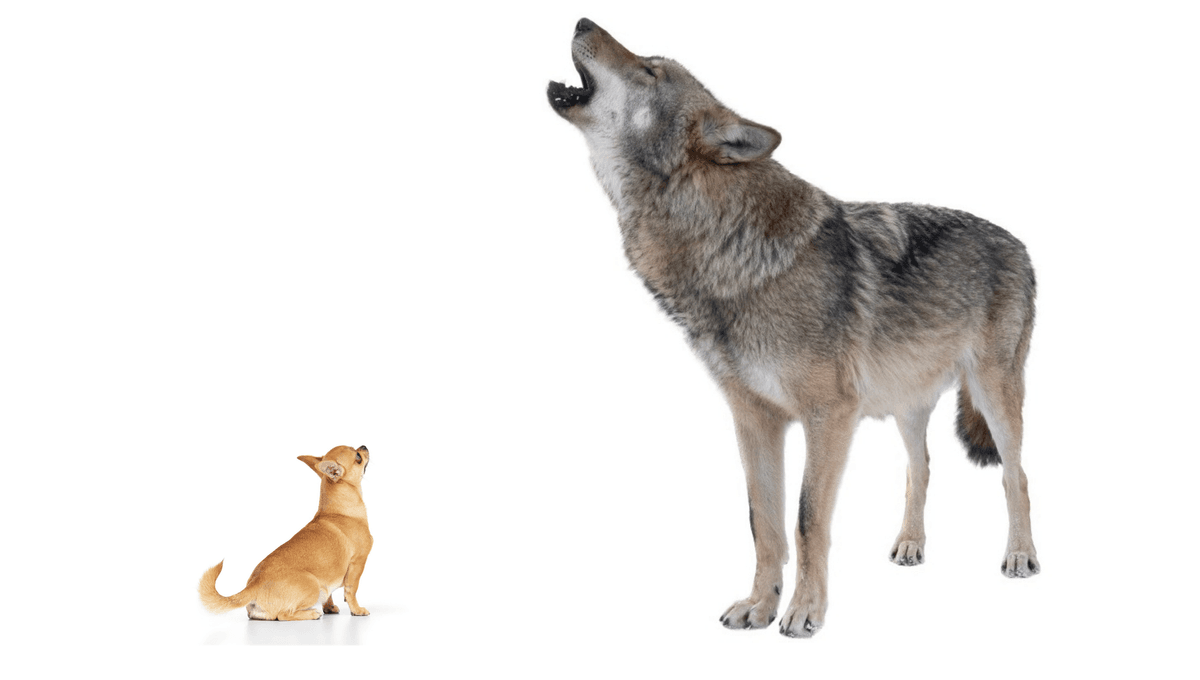

Simply put: we know dogs were once wolves. We know they’re not anymore – in fact, in some cases, they could hardly be further from the keystone apex predators that have struck fear and awe in equal measures into the heart of humanity since time immemorial. Which only leaves one question: how the hell did that happen? First question: when did wolves become dogs? Well, actually, they kind of didn’t. We thought they did – for a long time, actually. “It was such a long-standing view that the gray wolf we know today was around for hundreds of thousands of years and that dogs derived from them,” Robert Wayne, then an evolutionary geneticist at the University of California, Los Angeles, told Scientific American back in 2015. “We're very surprised that they're not.” Just as humans are not the direct descendant of chimps – rather, we’re two separate branches, equally distant from a single now-extinct ancestor – so too are dogs not simply “gray wolves 2.0”. In fact, the story is much more complex. By the time humans reached Europe, where the history of dogs really starts, wolves were already one of the most successful species on the planet: there were Beringian wolves in modern-day Alaska and Western Canada; cave wolves in Europe; Ethiopian wolves in the highlands of Africa and African wolves further south; there were even dire wolves across what is now the US and South America – although, of course, they weren’t actually wolves, just canines. It was probably one of these species that first decided, “ah, screw it; sure, those weird hairless monkeys have weapons, but they also have meat – let’s see if I can’t go be cute at them until they share with me.” But… well, it was also probably a bunch of others, too. “Dogs derive ancestry from at least two separate wolf populations,” said Anders Bergström, then a post-doctoral researcher in the Ancient Genomics lab at the Francis Crick Institute, in 2022. “[There was] an eastern source that contributed to all dogs and a separate more westerly source, that contributed to some dogs.” It’s a hypothesis that resolves one of the many, many longstanding mysteries around the origin of dogs – that is, where it happened. Some genetic analyses had pinpointed Central or East Asia; others Europe. The oldest known remains of something indisputably a dog are from Germany, but there are almost-contemporaneous remains of domesticated dogs in China, too. Even earlier dog-like canids have been found in the Basque Country in Spain and Czechia. The picture, basically, was a mess – but the answer was simple. “Maybe the reason there hasn’t yet been a consensus about where dogs were domesticated is because everyone has been a little bit right,” suggested Greger Larson, Director of the University of Oxford’s Palaeogenomics and Bio-Archaeology Research Network, in 2016. The domestication of the dog was, then, more of a wave than a single event – but when, roughly, did it occur? Well, on this at least, we have some more solid data – literally. That’s because, 14,000 years ago, in what is now Bonn, a pet dog died. We know it was a pet dog – not a tamed wolf, or a hunting buddy, or anything like that – because of the shape it was in: put simply, it was kind of a sickly thing, suffering from bad teeth, gum disease, and a canine distemper infection, plus a handful of other maladies, at various points in its short life. All of this ill fortune would have made the pup’s survival unlikely. “[C]anine distemper has a three-week disease course with very high mortality,” points out one 2018 paper from the Journal of Archaeological Science – so “the dog must have been perniciously ill during the three disease bouts and between ages 19 and 23 weeks.” “Before and during this period, the dog cannot have held any utilitarian use to humans,” it notes – and yet, it survived. How? “We suggest that at least some Late Pleistocene humans regarded dogs not just materialistically,” the authors conclude, “but may have developed emotional and caring bonds for their dogs.” Fourteen thousand years ago – and that’s a minimum, remember – puts the domestication of the dog firmly before the agricultural revolution. “It happened when people were still hunter-gatherers,” said Wayne. That’s borne out by genomic analysis, too: having sequenced the genomes of dozens of ancient dogs and wolves, in 2020 researchers at the Crick concluded that by the end of the last Ice Age, around 11,000 years ago, there were already five major dog lineages in the world. “This diversity means that the first dogs from which they all descend must have arisen several thousand years before that,” the researchers reported at the time, “well before the agricultural revolution and therefore predating all other domesticated species.” The journey from apex predator to humanity’s best friend, then, is one that happened a long time ago – before many developments that we may consider more characteristic of our species, like agriculture or pastoral living – and potentially many times over across the world. But none of that answers what we’re sure is the question you’re most interested in, which is: how the hell did it go down? Perhaps you have some image in your mind of Neolithic tribespeople spotting the potential in their lupine contemporaries – maybe abducting some pups and training them to live among humans, like a reverse Mowgli. You wouldn’t be alone: there’s certainly a school of thought that makes the domestication of the dog just another example of human ingenuity. “The technical advance that made humans so irresistible and so invasive – from 50,000 years ago until today – was in part their ability to form [an] unprecedented alliance with another species that we call domestication,” argued Pat Shipman, an anthropologist and author of The Invaders: How Humans and Their Dogs Drove Neanderthals to Extinction, in 2017. “We turned wolves into dogs,” she said, “and use[d] them to enhance our own survival in almost every habitat on the planet.” Others, though, aren’t convinced. “The now generally accepted view is that wolves essentially ‘self-domesticated’,” wrote Keith Dobney, Professor and Sixth Century Chair of Human Palaeoecology at the University of Aberdeen, in 2015. “This involved a more long-term relationship, driven initially not by direct human intervention but by the local ecological conditions they created,” he explained. “In this scenario, human leftovers drew certain wolves closer to campsites and perhaps led some individuals or even small packs to follow human hunters in search of easy pickings. The presence of wolves so close to human settlements perhaps also had the effect of preventing other dangerous carnivores from straying too close – creating a loose but mutually-beneficial partnership.” “Over time, these wolves became more and more accustomed to humans until eventually new selection pressures changed them from wolves to dogs.” The truth is, we’re not sure. There’s circumstantial evidence for both scenarios – and perhaps, as with the other questions surrounding dog domestication, both might even be correct. But one thing’s for sure: once humans settled down, the difference between “wolf”, “wolf-dog”, and “dog” became almost as stark as it is today. Past the agricultural revolution, there’s something of a sea-change in how dogs are found in the archaeological record. They become more specialized: small, medium, and large breeds start to turn up, with some revered for their abilities to safely guard or herd livestock and others for their tastiness. But it was the industrial revolution that really changed the way we see, live with, and think about dogs. “The changes wrought on dogs in the Victorian era were revolutionary,” said Michael Worboys, emeritus professor in the University of Manchester’s Centre for the History of Science and author of The Invention of the Modern Dog, in 2019. “As was the very adoption of ‘breed’ as way of thinking about and remaking varieties of dog.” “For most of history what dogs did counted more than [how they] looked,” he explained. “The types of dogs that existed were bred to do particular tasks, like to collect game that had been shot or to protect sheep from wolves.” But with the mass changeover from rural to urban living – plus various societal and technological changes that boosted Western societies a few rungs up Maslow’s ladder – such prosaic animals were no longer in high demand. People wanted cute, loyal pets; they wanted shiny coats and snub noses. They wanted Crufts and the Kennel Club. For better or for worse, they got it. A missing link

Man’s oldest friend

Who’s a good boy?

The birth of the doggo