A longstanding mystery surrounding the Vitruvian man – yes, that Vitruvian man – has a new solution. The weird part? It comes from inside your mouth.

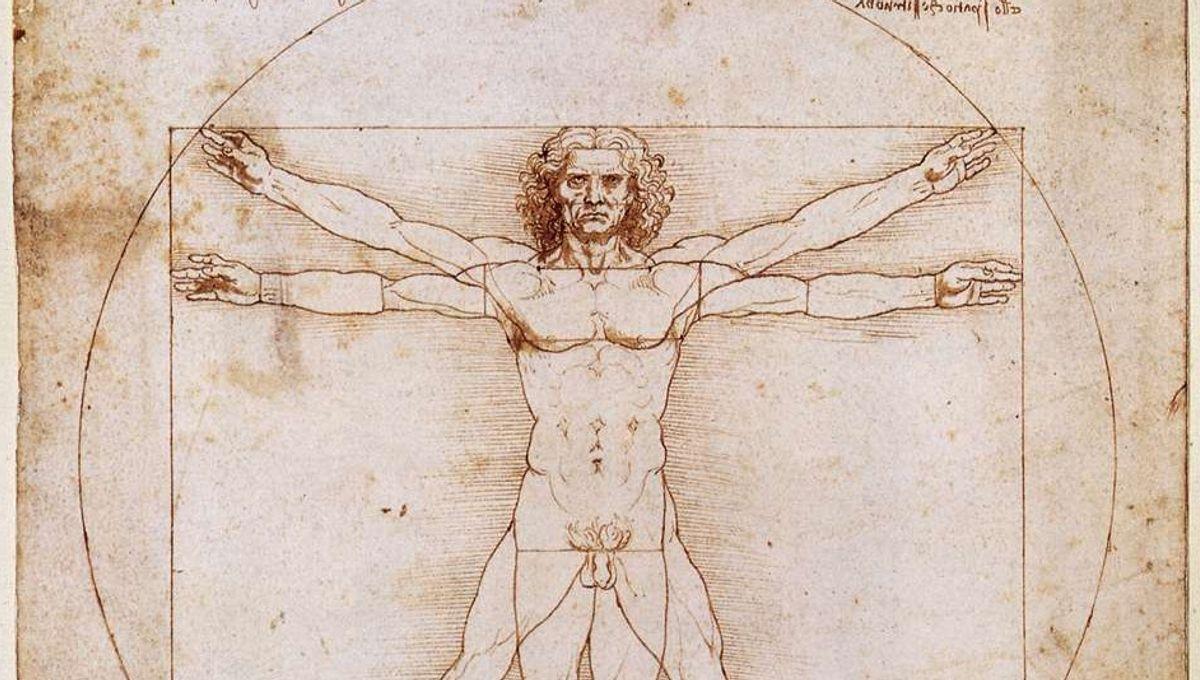

You know the Vitruvian Man. He’s perhaps second only to the Mona Lisa in terms of iconic imagery in Western history: a notebook sketch of a man in two positions, one standing straight and the other with arms and legs outstretched, superimposed upon each other and inscribed within both a square and a circle. It’s this guy: Kind of looks like he's doing the YMCA, don't it? He was, of course, drawn by Leonardo da Vinci, in around 1490 – but his history actually goes much further back. His design was inspired by the writings of Vitruvius – if you’ve ever wondered what’s up with the title of the work, that’s where it comes from – an Ancient Roman architect who, in his mid-20s BCE treatise De architectura, wrote: “In the human body, the central point is the navel. If a man is placed flat on his back, with his hands and feet extended, and a compass centered at his navel, his fingers and toes will touch the circumference of a circle thereby described. And just as the human body yields a circular outline, so too a square may be found from it. For if we measure the distance from the soles of the feet to the top of the head, and then apply that measure to the outstretched arms, the breadth will be found to be the same as the height, as in the case of a perfect square.” Now, you can see the ingredients there for da Vinci’s sketch – but crucially, no real recipe. Okay, you can draw a man standing inside a perfect circle and square, but where are the details? How big should one shape be compared to the other? Where should the center of each be? How would you even work that out? Looking at the finished product, it seems obvious – but it really wasn’t. Plenty of people had attempted to draw a figure according to Vitruvius’s design, all with varying degrees of success, and even da Vinci only really made it work after correcting a few details in the original description. But even as famous as the Vitruvian Man became, the exact system da Vinci used to design it has remained a mystery. Which is strange, really – because, as it turns out, he really did make it pretty obvious. “The search for Leonardo's geometric method has generated numerous theories, each attempting to explain the measured relationship between the circle and square in the original drawing,” writes Rory Mac Sweeney, the dentist behind the new Vitruvian hypothesis. Taking the ratio between the side of the square and the circle radius – around 1.64 – as a cue, “the most popular explanation has been that Leonardo employed the Golden Ratio (φ ≈ 1.618),” Mac Sweeney notes. “However […] this construction produces significant error – over 2 percent deviation from the actual measurements.” Alternative explanations for da Vinci’s particular construction came from other geometric figures: octagons, heptagons, and suchlike. But none of these hypotheses offered something Mac Sweeney saw as crucial: a reason for their choice. “They remain purely abstract mathematical exercises,” he writes, “without connection to Leonardo's documented interests in human anatomy, functional relationships, or natural principles.” “As geometric puzzles, they succeed,” he says. “As explanations of Leonardo's methodology and intentions, they fail to provide convincing rationale for his specific choices.” So, what does Mac Sweeney see as underpinning the Vitruvian Man’s proportions? Well, it’s actually surprisingly simple: “The solution […] has been hiding in plain sight within Leonardo's own manuscript notes accompanying the drawing,” he explains. “In his characteristic mirror script, Leonardo wrote: ‘If you open your legs enough that your head is lowered by one-14th of your height and raise your hands enough that your extended fingers touch the line of the top of your head, know that the center of the extended limbs will be the navel, and the space between the legs will be an equilateral triangle’,” Mac Sweeney points out. Ta-da! Image credit: Mac Sweeney, Journal of Mathematics and the Arts, 2025 (CC BY 4.0) In other words: Leonardo had literally told us all how he was designing the figure – we just hadn’t noticed. And the best part? Mac Sweeney thinks he knows why. This is where Mac Sweeney’s personal training comes into play. The equilateral triangle of the Vitruvian man seems to have stuck out to him in part because, as a dentist, he’s familiar with something very similar. “In 1864, dentist William Bonwill established that optimal human mandibular function is based on an equilateral triangle connecting the two mandibular condyles (jaw joints) to the midpoint of the lower central incisors,” he explains. You have to imagine it coming out of the screen towards you. Image credit: Mac Sweeney, Journal of Mathematics and the Arts, 2025 (CC BY 4.0) Bonwill’s triangle, as this configuration is known, isn’t just a neat piece of anatomical trivia. It’s such a good guideline for real life that modern dental instruments are based on it; our own faces follow it too, with the triangle “govern[ing] ideal tooth positioning, jaw relationships, and mandibular movements during function,” Mac Sweeney explains. What’s more, this triangle can be extended into three dimensions: “all teeth lie along the surface of an imaginary sphere with its center near the forehead (glabella),” Mac Sweeney writes, and “the mandible forms a tetrahedron with Bonwill's equilateral triangle as its base and its apex extending to the glabella.” While drawing it as a single image à la the Vitruvian Man would be difficult, overall, the idea being described is the same: you have the static anatomy, and a schematic of its dynamic capability, and the two are connected via this equilateral triangle. And as a bonus: the ratio of sizes between the two is about 1.63 – much closer to Leonardo’s 1.64. It’s far from the only time this ratio, or the equilateral-triangle setup that yields it, turns up in the human body. Mac Sweeney points to one study which “examined 100 human skulls and identified a consistent ratio of 1.64 ± 0.04 in cranial architecture, measuring the nasioiniac arc (curved distance from nasion to inion along the skull surface) against the parieto-occipital arc (curved distance from bregma to inion).” “This ratio appears exclusively in humans,” he notes, “and represents optimal structural relationships within the skull that closely approximate the tetrahedral ratio.” Short of finding another surprise explanation in his notebooks, there’s no way to know what was going through old Leo’s mind when he drew what he did. But if Mac Sweeney’s hypothesis is correct, it suggests that this 15th century scholar had a surprisingly modern understanding of human anatomical proportions. It would hardly be out of character for da Vinci if that were the case. He was obsessed with the human body – his notebooks are filled with strikingly accurate sketches of various figures and features – and believed in a universe where mathematical beauty and the natural world were intrinsically connected. That he would have noticed and exploited such a geometrical relationship to the human body is eminently believable. “From the hexagonal close packing of atoms to the tetrahedral architecture of dental occlusion to the cranial proportions found exclusively in humans, we observe consistent mathematical relationships encoded in biological form,” Mac Sweeney writes. “Vitruvian Man stands as a testament to Leonardo's insight that human proportions reflect deeper mathematical principles governing optimal spatial organization.” The paper is published in the Journal of Mathematics and the Arts.The Renaissance man

A missed clue

A Vitruvian jaw

Ahead of his time