-

Fil d’actualités

- EXPLORER

-

Pages

-

Blogs

-

Forums

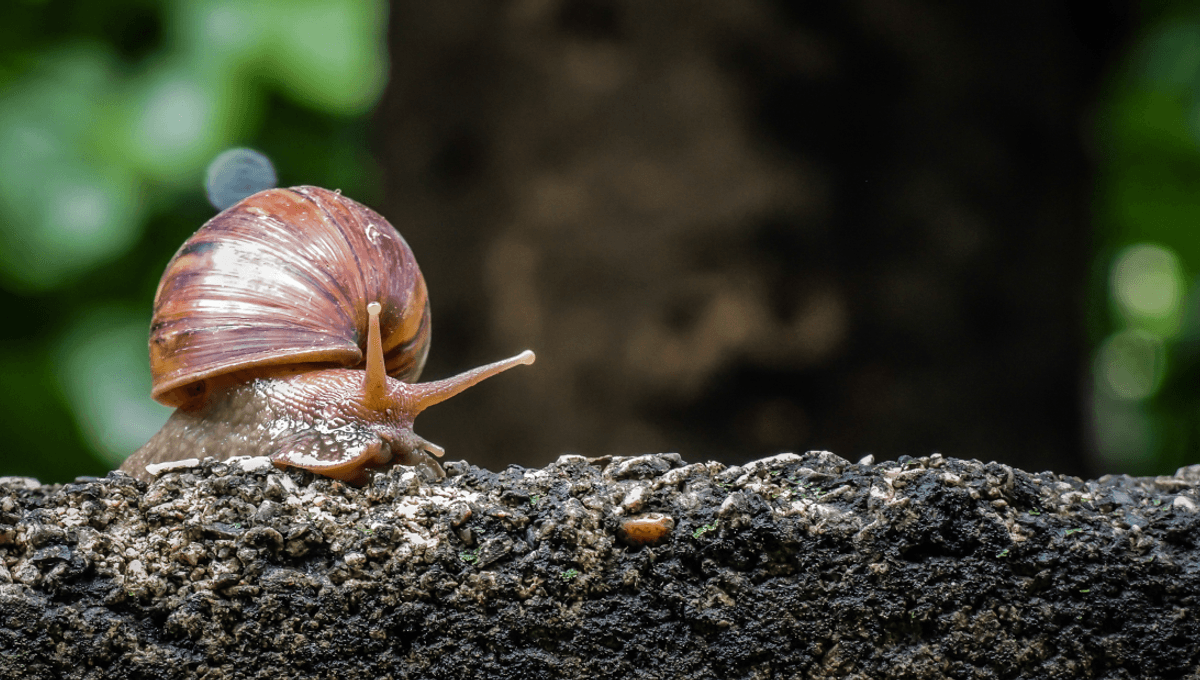

Garden Snails Now Venomous According To Radical Redefinition, And Things Get Surprisingly Sexy

Turns Out Garden Snails Are Venomous, It's Just A Much Sexier Kind Of Venom

What words spring to mind when you think of the common garden snail? Slow? Slimy? Venomous? You might be raising your eyebrows at that last one, but according to a new study, humble garden snails are just one of a slew of new venomous animals under a fresh definition of the concept.

The radical redefinition of what constitutes venom argues that any secretion that brings about a “negative extended phenotype” in another living thing qualifies. So, fangs or no fangs, if your particular goop variety does something to another living animal that’s beneficial to you, it counts as venom. “This redefinition helps us understand venom not as a narrow weapon, but as a widespread evolutionary strategy,” said study lead Dr Ronald Jenner, London Natural History Museum’s venom expert, in a statement. “If you look at what the proboscis of a mosquito does when it’s in your skin, it injects toxins that suppress the immune system so that the animal can safely take a blood meal without being swatted away. On a molecular level it shows a lot of similarities to what happens when a viper bites, say, a bunny.” “Conceptually they work on exactly the same system: a conflict arena between two organisms that is mediated by injected toxins. And that’s venom.” The new definition means that everything from aphids to slugs are falling into the venomous ranks alongside snakes and spiders. A seemingly unrelated group of animals, but one whose secretions have a shared goal: to manipulate other living things. Examples include cicadas, aphids, and shield bugs, who all use secretions to disable plant defenses while they’re busy sucking sap. In fact, the earliest known examples of venoms found in the animal groups Hymenoptera (which is your wasps, bees, and ants) and Hemiptera (hello bugs and aphids) targeted plants, too. Animal-targeted venoms didn’t emerge until much later. Venom gets a bit sexy among the garden slugs and snails, some of whom fire darts laced with toxins to influence the behavior of potential mates (there are other snail species that are famously venomous, like the cone snails). Blowflies, meanwhile, used their barbed phalluses to inject females with something that prevents them from mating again. When it comes to venom, this new study argues, there’s so much more to manipulative gloop than predation. Though a bit of a PR makeover for the humble garden snail, the authors argue the definition change could be pivotal in opening up new avenues of venom research. Better understanding the less traditional instances of venom use in the animal kingdom could, in time, lead to all kinds of discoveries, including leaps forward for the pharmaceutical industry, to more environmentally friendly agricultural practices. And if that snail starts looking a little too good, best check yourself for love darts. The study is published in the journal Trends in Ecology & Evolution.