-

Новости

- ИССЛЕДОВАТЬ

-

Страницы

-

Статьи пользователей

-

Форумы

Defying Logic: Symmetrical Crystals Can Interact With Light Asymmetrically

Defying Logic: Symmetrical Crystals Can Interact With Light Asymmetrically

Crystals that are perfectly symmetrical around a central point can nevertheless respond to light as if they were asymmetric, scientists have found. The discovery could lead to more sensitive measuring devices, improve the security of signal transmission, and even allow brighter optical displays, researchers claim.

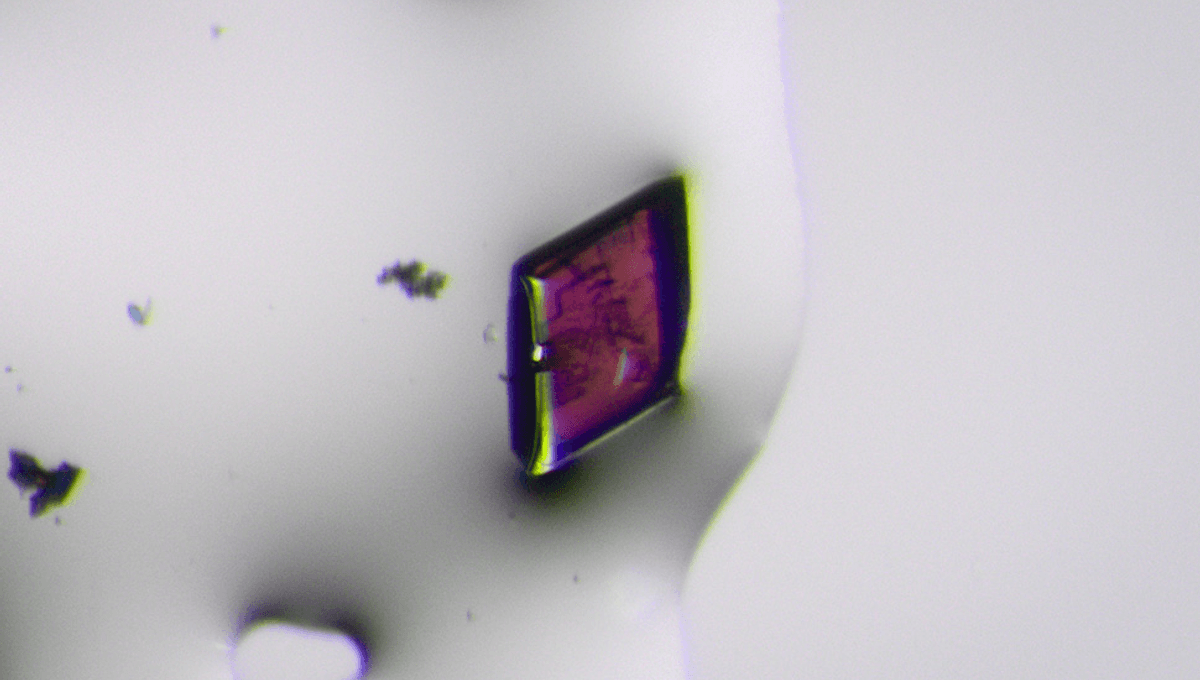

Symmetry comes in many forms. Our bodies, up to a point, have left-right symmetry, but not top to bottom. If you don’t believe me, try reversing a photograph of yourself, then flipping it upside down. Centrosymmetry represents a particularly high level of symmetry, one important in crystallography. Centrosymmetric crystals are symmetric in every direction from their center. If you draw a line that passes through the center, the crystal will be symmetrical around it, whether the line is vertical, horizontal or at any angle between. An object with such consistent symmetry should respond the same way to light coming from one direction or its mirror image, right? Likewise, if exposed to circularly polarized light (ie light that approaches in spirals), it shouldn’t matter if the light is polarized clockwise or anticlockwise. At least so you would think, and scientists did. Yet somehow, when chemists put this to the test, they found the direction of polarization matters a lot. Li2Co3(SeO3)4 crystals absorb more clockwise polarized light than if it is anticlockwise (or the reverse, depending on the crystal). “This discovery is surprising to many in the scientific community whom, for a long time, thought this principle was impossible,” said Dr Roel Tempelaar of Northwestern University in a statement. “Crystals are really categorial because of their symmetry. You can infer a lot about their behaviors — without doing complicated calculations or measurements — just by looking at their symmetry. Now, we realize that sometimes there is more than meets the eye.” The expectation that symmetric crystals should behave symmetrically is so logical most people considered it a waste of time to test it. Tempelaar and colleagues were inspired to go where others had not because they had been studying the chirality of molecules. Chiral shapes are those that cannot be perfectly superimposed on top of their mirror images. A glove put on the wrong hand won’t fit (does not apply to very soft and flexible gloves) because it is chiral, as are your hands. Chirality in molecules is common, and sometimes very important. “Many molecules come in two ‘flavors,’” Tempelaar said. “They have a ‘right-handed’ form and a ‘left-handed’ form. By studying their interactions with chiral light, you can diagnose what type of molecule you have. Sometimes the right-handed version is a powerful drug, but the left-handed version is poison.” Biochemists have long been puzzled by why the sugars in DNA and RNA are always right-handed, while the amino acids life on Earth combines into proteins are always left-handed, given that mirror images of both exist. A possible solution was proposed last year, but the question is not considered settled. In exploring molecules’ chirality, Tempelaar and colleagues wondered how applicable their work was to crystals. Their models suggested that even centrosymmetric crystals could show apparent chirality. “Owing to its high degree of symmetry, a centrosymmetrical crystal traditionally is not expected to exhibit chirality,” Tempelaar said. “But we were optimistic about our level of predictivity because we had already rationalized this particular phenomenon in a variety of molecular samples. We didn’t expect the physics in a crystal to behave any differently.” The team tested their predictions and found them confirmed. They attribute the difference in absorption to; “A photophysical process not previously characterized for crystalline solids.” This is a product of the electronic dipoles within the crystal. “To our knowledge, no centrosymmetrical crystal has been reported to do this,” Tempelaar said. “But we had success with the first material we tried. We are very excited about this. It’s opened our eyes to start looking at a variety of centrosymmetric materials in a new way.” The findings are so new, applications remain theoretical, but with information technology research increasingly focusing on photons rather than electrons, an extra way to control light could have powerful implications. Notably, the process the authors consider responsible for this unexpected asymmetry has also been observed, although in a less ordered fashion, in metal halide perovskites – the materials considered the likely future of solar power. The discovery is published in the journal Science.