9,500-Year-Old Headless Skeleton Is New World’s Oldest Known Cremated Adult

9,500-Year-Old Headless Skeleton Is New World’s Oldest Known Cremated Adult

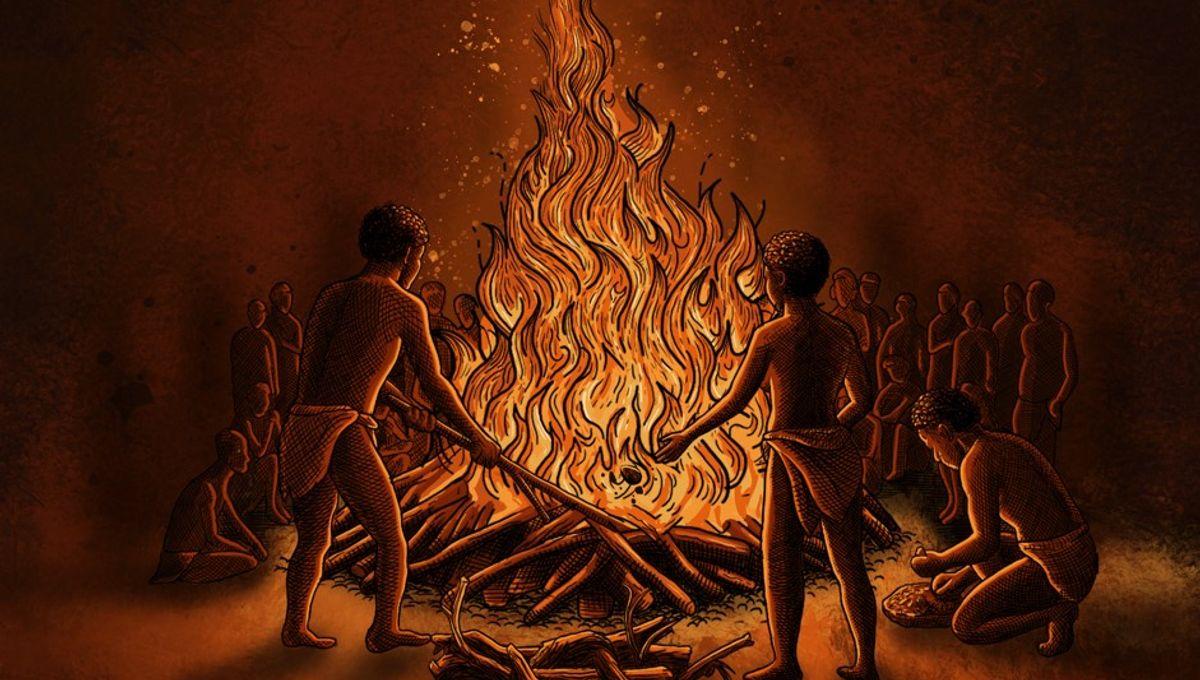

For prehistoric hunter-gatherers, building a funeral pyre to cremate their dead was a real faff, and simply wasn’t worth all the effort or the investment in terms of the amount of valuable firewood required to burn a human body. However, new research shows that a Stone-Age community in Malawi did in fact honor a female tribe member with a blazing send-off, challenging everything we thought we knew about Palaeolithic mortuary practices.

The rest of this article is behind a paywall. Please sign in or subscribe to access the full content. “We report the earliest evidence for intentional cremation in Africa, the oldest in situ adult pyre in the world, and one of only a few associated with hunter-gatherers,” write the authors of a new study about the remarkable discovery. By analyzing the charred, fragmented skeleton, the researchers determined that the recipient of this unique ritual was a petite adult female, standing a little under 5 feet tall (between 145 and 155 centimeters). "Cremation is very rare among ancient and modern hunter-gatherers, at least partially because pyres require a huge amount of labor, time, and fuel to transform a body into fragmented and calcined bone and ash," said lead study author Jessica Cerezo-Román in a statement. To date, the oldest known example of a cremation pyre comes from Alaska, where the carbonized remains of a toddler were dated to about 11,500 years ago. Within Africa, there is evidence of burned human remains at a 7,500-year-old site in Egypt, although these are not associated with actual pyres and therefore don’t represent deliberate cremation. Firm evidence for such practices only emerges in the Neolithic, when pastoralists in Kenya began burning their dead around 3,300 years ago. Based on the layers of ash and fragmented bone at the cremation site, named Hora 1, at Mount Hora in Malawi, however, the researchers determined that this woman’s cremation took place 9,500 years ago on a pyre that was built using 30 kilograms (66 pounds) of wood and dried grass. "Not only is this the earliest cremation in Africa, it was such a spectacle that we have to rethink how we view group labor and ritual in these ancient hunter-gatherer communities," says study author Jessica Thompson. Analyzing cut marks on the bones, the researchers discovered that the cremated woman was probably de-fleshed before being placed on the pyre. "Surprisingly, there were no fragments of teeth or skull bones in the pyre," explained study author Elizabeth Sawchuk. "Because those parts are usually preserved in cremations, we believe the head may have been removed prior to burning," she adds. Cut marks on the right radius (forearm) suggest the woman was defleshed before being placed on the pyre. Image credit: Jessica Thompson Exactly what happened to the woman’s skull is a mystery, although the researchers say it may have been used as ancestor-worship rituals by the woman’s community. A further analysis of charred material at the site indicates that people continued to light enormous pyres at the site for hundreds of years after the fiery funeral, yet no more people were ever actually cremated there. Instead, the study authors suggest that these subsequent “pyrotechnological spectacles” might have been staged in remembrance of the mortuary ritual that once took place at Hora 1. Taken together, these findings indicate that the cremated individual was highly revered by her community for generations following her death, although her identity and social rank remain unknown. "Why was this one woman cremated when the other burials at the site were not treated that way?" ponders Thompson. "There must have been something specific about her that warranted special treatment." The study has been published in the journal Science Advances.