-

Web sayfası bildirimcisi

- EXPLORE

-

Sayfalar

-

Blogs

-

Forums

Hubble Telescope’s Bite Of Dracula’s Chivito Reveals Chaos In The Largest Known Planet-Forming Disk

Hubble Telescope’s Bite Of Dracula’s Chivito Reveals Chaos In The Largest Known Planet-Forming Disk

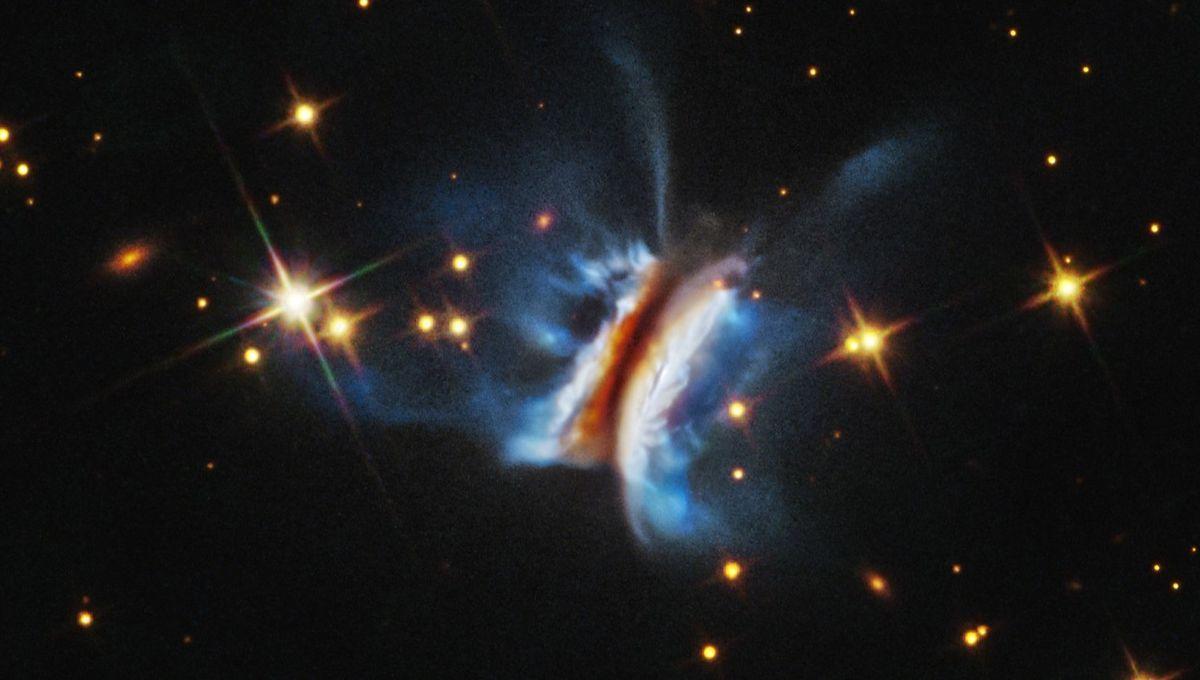

The largest planet-forming disk ever observed, nicknamed Dracula’s Chivito after a Uruguayan sandwich, has been revealed to be exceptionally chaotic. This turbulence may have propelled whisps of material visible far beyond the main disk, creating a butterfly-like appearance.

The rest of this article is behind a paywall. Please sign in or subscribe to access the full content. Early last year, astronomers discovered a very strange-looking disk around a young star, officially titled IRAS 23077+6707. When it was given the nickname Dracula’s Chivito, we called it the best-named astronomical object of the year, even though it was only February, and we’re happy to stand by that. From the start, IRAS 23077+6707 was more than a cool name, however. For one thing, aside from objects too small to see clearly, we’d only ever seen one apparently similar object, IRAS 18059-3211, known as Gomez’s Hamburger, which was found back in 1985. Both cosmic edibles are very young stars surrounded by disks that will eventually become planets, which look strange because we see them side-on. Each disk has so much dust that the star itself is obscured, creating the impression of a dark patty between bright buns or bread. The initial observations indicated that while the star at the center of Dracula’s Chivito is only two to four times more massive than the Sun, the disk contains much more material than all the planets and asteroids in the Solar System combined. A few months later, we discovered this is one loaded chivito, following the discovery that the disk holds more ingredients that will eventually become planets than any counterpart we have ever seen. Clearly, it was time to bring in the big guns, and the Hubble Space Telescope’s operators heeded the call, with observations made using six filters. Hubble has provided far sharper images of IRAS 23077+6707 than ground-based telescopes could manage. They confirm its enormous size, 4,200 astronomical units, or 630 billion kilometers (391 billion miles) across; 40 times larger than the distance out to the outer edge of the Kuiper Belt, where many comets originate. Hubble's image with filters, coordinates, and scale bar. The scale is only approximate because we don't know Dracula's Chivito's distance very precisely, but if it's right, that bar is 50 times the distance from the Sun to Neptune. Image credit: NASA, ESA, STScI, Kristina Monsch (CfA); processing: STScI/ Joseph DePasquale Consequently, even at a distance of 1000 light-years, Dracula’s Chivito takes up more of the sky than any other planet-forming disk ever spotted, including much closer ones. That angular diameter means we can see more detail than in other disks. “These new Hubble images show that planet nurseries can be much more active and chaotic than we expected," said lead author Dr Kristina Monsch of the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian in a statement. The IRAS 23077+6707 disk is thought to contain between 10 and 30 times the mass of Jupiter. We know of individual planets with the lower end of that range (and brown dwarfs at the higher end), sometimes with other companions in the same system. Consequently, it’s no surprise that disks this massive exist since such giant planets must have come from somewhere. Nevertheless, they’re so rare, and this stage so fleeting, that finding one within range to see is a shock. Indeed, astronomers are still confused about how it was missed for so long. "We're seeing this disk nearly edge-on and its wispy upper layers and asymmetric features are especially striking,” Monsch added. “Both Hubble and NASA's James Webb Space Telescope have glimpsed similar structures in other disks, but IRAS 23077+6707 provides us with an exceptional perspective – allowing us to trace its substructures in visible light at an unprecedented level of detail. This makes the system a unique, new laboratory for studying planet formation and the environments where it happens." Disks like this are usually fairly symmetrical, so the fact that the filaments extend so far from the disk to the north, but are absent on the south side, is another puzzle astronomers are keen to explain. "Hubble has given us a front row seat to the chaotic processes that are shaping disks as they build new planets – processes that we don't yet fully understand but can now study in a whole new way,” said co-investigator Joshua Bennet Lovell, also of the CfA. The team remains uncertain as to whether dust is still falling onto the disk, as some previous observers have argued. Observations at longer wavelengths, less blocked by dust, should reveal much more. However, given that we don’t even know if there is one star at the center of IRAS 23077+6707, or two in a tight orbit, it’s probably best not to expect to answer all the questions soon. A disk like this seen side-on can look like a missed opportunity compared to one seen face-on, but the authors note our perspective offers advantages as well. By blocking most of the star’s light, the dust prevents it from blinding us to everything else, as would usually occur, making structures lit up by the light above and below the densest disk much easier to spot. The study is published in The Astrophysical Journal._0.jpg)