Did you know that Elasmosaurus was once depicted as being the other way around? And by that, I mean Edward Drinker Cope put its head on its tail? Then we have Iguanodon, an animal we once thought had a fierce horn on its nose because we erroneously put the thumb spike on its face.

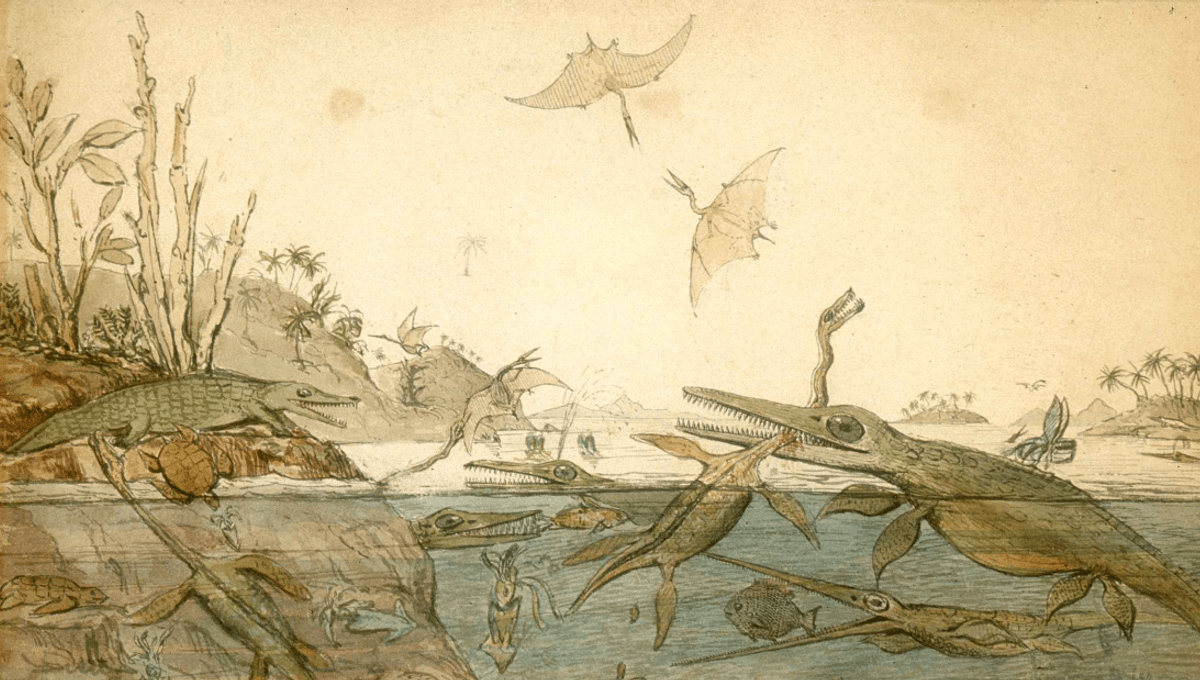

The rest of this article is behind a paywall. Please sign in or subscribe to access the full content. It’s not easy putting extinct animals together. Imagining new-to-science species from the fossil record is a bit like trying to piece together squashed, shattered LEGO with half the pieces missing. Thankfully, there are skilled and talented people who can do just that. I’m talking, of course, about palaeoartists. 2025 has been a great year for palaeoart with Walking With Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Planet: Ice Age both landing on our screens. It’s easy to see how the practice has developed since earlier works like "Duria Antiquior" by geologist Henry De la Beche (pictured at the top of this article). It’s a beautiful piece of art, but as science and technology marches on, so too has palaeoart. Now, an emerging technology is churning out dinosaur imagery like there’s no tomorrow, but is it any good? Palaeoart combines science with artforms such as illustration, painting, sculpture, and animation to create life-like recreations of animals that are extinct. Dinosaurs and pterosaurs are popular subject matters, but it can encompass any animal, plant, fungi, or ecosystem that’s no longer around. The practice has produced beautiful images, but it also has an important part to play in scientific research. A key part of science communication is helping others (scientists or otherwise) to understand what a new-to-science species would’ve looked like, but creating such art isn’t easy. An illustration of Fona herzogae by Jay Balamurugan. “I spent a lot of time studying the known fossils of the animal, as well as those of related Thescelosaur dinosaurs. I made sure to include specific details present in that material, such as a stiffened tail and spurs on the forearms. I studied musculature models of related species to ensure the animal was appropriately bulked out in the right places. Modern animals that lived similar lifestyles were used to infer colouration and patterns. And finally, I framed the piece with leaves - each one being an exact match to a fossilised leaf found from the same approximate time period and location.” Image courtesy of Jay Balamurugan “Reconstructing the appearance of an extinct animal is a challenging process that requires a strong understanding of the fossil material available, a good grasp of both living and extinct animal anatomy, collaboration with palaeontologists, and a degree of artistic ability,” palaeoartist, TV producer, and science communicator Jay Balamurugan told IFLScience. “When I start any piece of paleoart, I go through each of these steps – first reading papers and fossil descriptions, then spending time understanding any skeletal or musculature diagrams, observing modern animals that share similar traits or features, and often speaking to the scientists actively studying the animals in the field or lab.” Many palaeoartists are scientists, too, such as biologist Andrey Atuchin. “I’m a palaeontologist myself to some degree,” he told IFLScience. “I take part in research. I have scientific publications. I also have a biology degree, so comparative anatomy and all those disciplines are not abstract for me. Basically, the same way scientists reconstruct extinct life in their studies – I do the same, but in graphic form.” "I often make a 3D sculpture of the animal first, to figure out the anatomy and lighting. With a modern swallow, for example, we know exactly how it looks – we can see photos, specimens, a living bird. With extinct animals, you can’t do that. So I build the creature myself as a 3D model, and then I draw it based on having that reconstruction in my hands and having the concept." Unless you’ve been living under a blissful, slop-free rock, you’ve likely already encountered AI image generation. In its infancy, you could identify AI a mile off (Will Smith eating spaghetti, anyone?) but it too is developing. So, could it be a useful tool in exploring ancient life? “At the moment, I've not seen generative AI successfully reconstruct any extinct animal with any degree of success,” says Balamurugan, and that could be for one simple reason: “GenAI makes use of existing data to create an output – this doesn't work when there isn't existing data to work from.” Any attempts at creating a dinosaur with GenAI rely on it learning from existing reconstructions of dinosaurs, which are almost always going to be existing artwork made by artists that have not consented to their work being used to train these systems. Jay Balamurugan “It can create a pretty solid likeness of a human because it is fed untold amounts of media featuring humans, but it can't create an extinct dinosaur because we don't have extinct dinosaurs that it can feed on. Therefore, any attempts at creating a dinosaur with GenAI rely on it learning from existing reconstructions of dinosaurs, which are almost always going to be existing artwork made by artists that have not consented to their work being used to train these systems.” An example Balamurugan highlights is the head of Jurassic Park’s T. rex that keeps cropping up on the bodies of AI dinosaurs because, quite simply, it’s the most widely circulated dinosaur. This was demonstrated in some questionable postcards sold earlier this year by a US state park, shared by palaeontologist Jim Kirkland, that churned out what appears to be the armored dinosaur Gastonia with – you guessed it – the head of a T. rex. Nice try, AI. For Atuchin, AI’s shortcomings are a byproduct of the way existing AI systems function. “These models don’t understand anything,” he said. “Not anatomy, not biomechanics, not evolution. They don’t analyze, don’t reason, and can’t create anything genuinely new. It’s just an elegant remix. A blend of whatever was loaded into them. The most probable and the most average.” There’s been much debate about whether “AI art” should even be considered art, not least because of the ethical issues surrounding the artwork that’s used to train these models and the lack of consent in their enrolment. Add to that the environmental cost each generation represents as data centers guzzle up 110 million gallons of water annually to cool servers. Still, I was curious to know if these artists saw any future potential for AI as palaeoart’s applications grow more complex. Something Balamurugan, series assistant producer on Walking With Dinosaurs – one of the most groundbreaking dinosaur documentaries to date – has some experience with. “I think there is an important distinction to be made with AI as a whole and generative AI – there are some uses for AI in the field of palaeontology when it comes to parsing large amounts of data or sorting through fossil catalogues, and this sort of thing will eventually trickle down to paleoart reconstructions in small ways,” she said. “After all, the more we understand in palaeontology, the better informed the resulting paleoart will be.” “There are even AI or AI-adjacent tools that have been used in 3D art for many years, such as things like cloud or water simulations for VFX. However, I don't see a use for this current wave of generative AI in palaeontology or paleoart, and I think its use is detrimental to the field and science communication.” From too many fingers on the human hand to a T. rex head on Gastonia, it seems AI has a long way to go stylistically. They say art is subjective, but much of what AI produces has a sheen born of blended textures, idealized shapes, and noise reduction that Atuchin describes as “plastic,” but as for harms? It goes much further. For real palaeoart – where accuracy, evidence, and anatomical logic matter – it can’t replace trained experts. Andrey Atuchin “The main problem is scientific accuracy,” said Atuchin, whose work is featured in the recently published Mesozoic Art II. “These models constantly invent anatomy: mixing different taxa, adding random muscles, creating impossible joints, soft tissues that completely break biomechanics. The image might look polished, but it has zero value, and people – especially media – often mistake it for something evidence-based because it makes images more and more believable each time." “AI is fine as a generic creative tool, as long as it’s clearly labelled and nobody confuses it with scientific reconstruction. But for real palaeoart – where accuracy, evidence, and anatomical logic matter – it can’t replace trained experts, and it should be used very carefully.” In an era where we're already facing an uphill battle in tackling widespread misinformation, it seems AI has the potential to muddy the already murky waters now that seeing is no longer believing. Perhaps, then, the work of palaeoartists could be seen as life rafts of science-backed information in a sea of AI slop. And anyway, before that metaphor drifts too far, who wants to be writing prompts all day when you can make like De la Beche and crack out the watercolors? After all, art is good for us (even when we're bad).

Palaeoart and Artificial Intelligence (AI)

AI – Can it be a helpful tool for palaeoart?

Could AI harm palaeoart?