-

Ροή Δημοσιεύσεων

- ΑΝΑΚΆΛΥΨΕ

-

Σελίδες

-

Blogs

-

Forum

First-Known Instance Of Bees Laying Eggs In Fossilized Tooth Sockets Discovered In 20,000-Year-Old Bones

Sweet Baby Beesus! These Ancient Bees Laid Their Eggs In The Vacant Tooth Holes Of Fossilized Mammals

Nature can be pretty metal when it wants, and a testament to this is the recent discovery that bees sometimes use hollowed out tooth sockets in fossilized skulls as a nesting site. That’s according to remains that date back to the late Quaternary period found in a cave, and it marks the first-known instance of this behavior in bees.

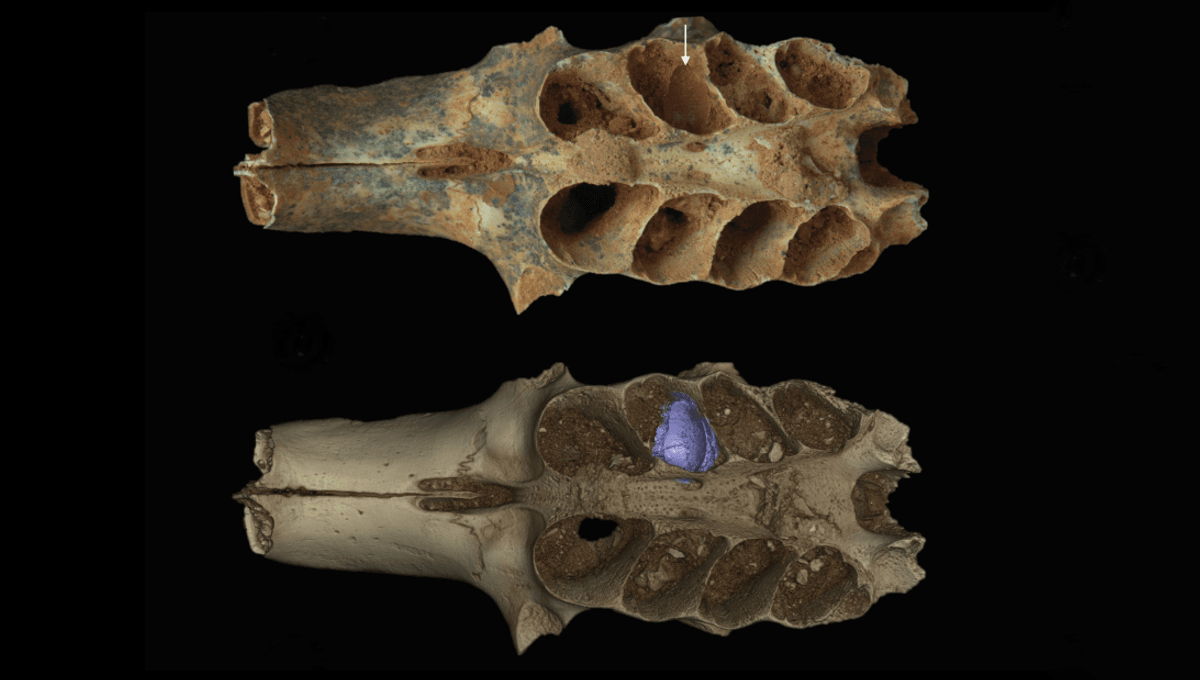

The rest of this article is behind a paywall. Please sign in or subscribe to access the full content. This story takes us to an ancient and very curious cave system on the Caribbean island of Hispaniola. It’s an island riddled with limestone caves, which is why you find sinkholes every 100 meters or so. We found tens of thousands of fossils in these caves, including rare species of rodents, sloths, monkeys, tortoises, crocodiles, and several new species of birds, mammals, and lizards. Lazaro Viñola López If that sounds dangerous, it is, and it’s been catching out unsuspecting wildlife for millennia. Their loss is our gain, however, as we’ve found the fossilized remains of all kinds of fascinating creatures in these cave systems. “We found tens of thousands of fossils in these caves, including rare species of rodents, sloths, monkeys, tortoises, crocodiles, and several new species of birds, mammals, and lizards,” lead author Lazaro Viñola López, a postdoctoral researcher at the Field Museum in Chicago, told IFLScience. “But I think the most unexpected of all were these bee nests inside the remains of extinct species. That is not something we were expecting and has shown to be a completely undocumented behavior in bees.” So unexpected were these nesting sites that the scientists say they could have easily scrubbed them away, thinking it was just dirt. Nesting inside the cavities of fossils was probably a good way to keep developing babies safe from predatory wasps. Image credit: Illustration by Jorge Machuky It all began with the discovery of ancient owl pellets – a gross but normal part of their digestion where they essentially vomit what looks a bit like poop. It contains the bones of animals they ate, which for the Hispaniola fossils, included a few mammal jaws. Some of these jaws had strange sediment filling the cavities where their teeth once were. That the teeth were missing wasn’t unexpected because rodents have ever-growing teeth with no roots, so once their soft tissues decompose, the teeth just fall out. What was unexpected was that in their place was something that looked to the scientists like ancient wasp cocoons. So, it seemed like these strange bumps were worth closer inspection and a good thing, too, because when they took CT scans of the bones, it revealed structures just like the mud nests bees alive today build. Some of the cavities even contained grains of pollen – a little snack left behind by bee mothers for their babies to eat. Our goal now is to continue documenting the diversity of vertebrates found in this cave, which so far exceeds 50 species, including several new ones for science. Lazaro Viñola López Solo bees are known to nest in everything from holes in wood or the ground to empty snail shells, as seen in some European and African species. We've even found evidence of bees damaging human bones at the Necropolis of Pill'e Matta in Quartucciu, Sardinia, but this marks the first time we've seen bees making use of pre-existing cavities for a cosy nesting spot that likely kept developing baby bees safe from predatory wasps. Conditions in the cave mean none of the bees themselves were preserved, but the nests have been classified as Osnidum almontei after Juan Almonte Milan, the scientist who first discovered the cave. It’s possible the bees responsible are still alive today, but like many of the remains found in the cave, it’s also possible they’re already extinct. So, bees lay their eggs in holey fossils. That’s something you now know, and it’s just another example to add to a growing list of quite how remarkable Earth’s bee species are. For Viñola López, it’s also a reminder to be very careful when inspecting fossils, as you never know when a seemingly insignificant bump of mud is going to turn out to be a new-to-science behavior, and there could be plenty more where that came from. “Our goal now is to continue documenting the diversity of vertebrates found in this cave, which so far exceeds 50 species, including several new ones for science,” he told IFLScience. “We have collected from this cave thousands of fossils, most of which we still have to identify and describe.” The study is published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B Biological Sciences.