Whether or not you believe in the Bible, it’s undeniable that it affects you today. That’s true even for the most ardent atheist out there – and according to a new study from Nathan MacDonald, Professor of the Interpretation of the Old Testament at the University of Cambridge, that’s because of one frankly slightly janky Bible map from 500 years ago.

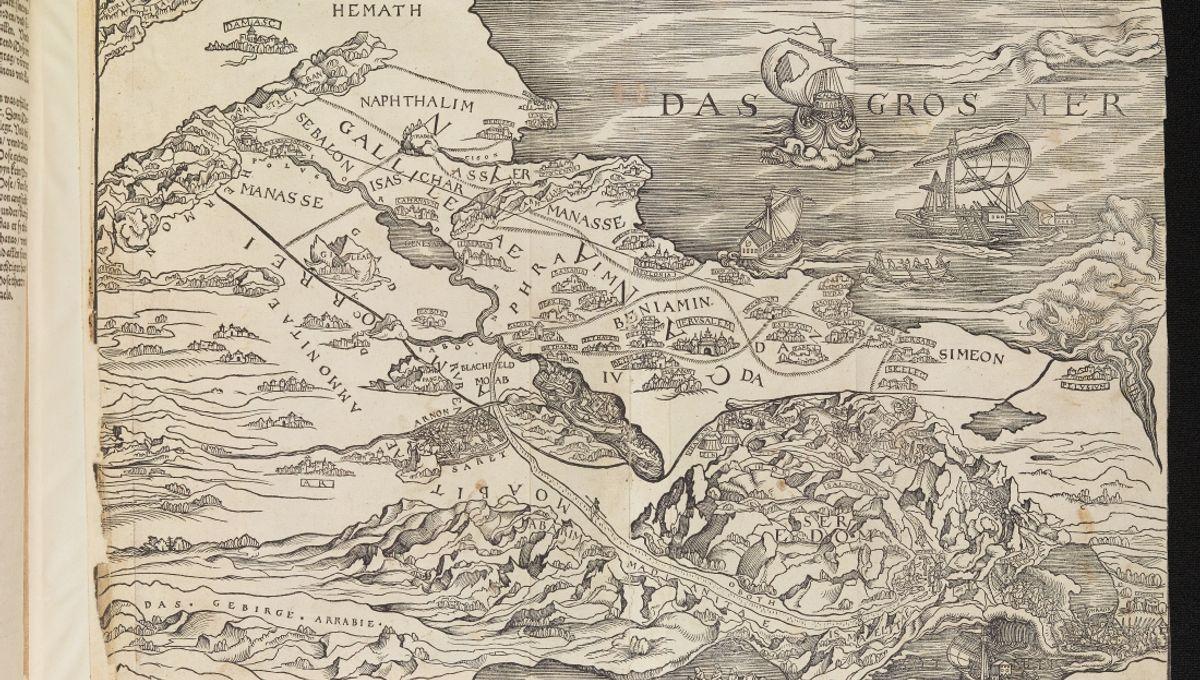

The rest of this article is behind a paywall. Please sign in or subscribe to access the full content. “This is simultaneously one of publishing’s greatest failures and triumphs,” MacDonald said in a statement about his work on Lucas Cranach the Elder’s map, printed in Zurich in Christopher Froschauer’s 1525 Old Testament and the first cartographical work to be included in a Bible. “They printed the map backwards,” he pointed out, “so the Mediterranean appears to the east of Palestine. People in Europe knew so little about this part of the world that no one in the workshop seems to have realised.” But as inaccurate as it was, the map would go on to not only change the way people thought about the Bible, but also how we think about the world itself. Why? Because it brought us the concept of political borders – and the equally made-up idea that they have some kind of physical truth to them. “As more and more people gained access to Bibles from the 17th century, these maps spread a sense of how the world ought to be organized and what their place within it was,” MacDonald said. “This continues to be extremely influential.” Professor MacDonald with the map as it appears in the 1525 Old Testament. Image credit: University of Cambridge For many Christians today, the Bible is one of those very few permanencies in the world. It connects them to a world thousands of years old, with the messages and meaning conveyed as equally in the modern world as they were in the ancient one. That, however, is a fiction. “The Bible has never been an unchanging book,” MacDonald says. “It is constantly transforming.” The version considered in the new study is a striking example of precisely one such transition. While maps inside Bibles are pretty standard today, they simply didn’t exist before the 16th century – after all, why would they? “Before the Reformation the Bible was mainly read by a priest to a church community during an act of worship, and usually in Latin,” explains the Musée Protestant. It wasn’t until the rise of Protestantism, and a focus on preaching, the gospel, and individual relationships with the divine, that “reading the Bible became the heart of the liturgy,” the museum notes, and “believers could read it in their own language.” And with this rise in the importance of the Bible itself, rather than religious teaching from the authority of the church, came a different phenomenon: the idea that the stories recorded in the Bible were literally, physically true. They happened in a specific time, and specific places, people began to say – and so, we should be able to mark it all on a map, right? “Early in the movement’s history, Protestants showed an interest in maps and their potential to provide an alternative paratextual apparatus that emphasized the literal meaning of the text,” MacDonald argues in his paper. Believers may not have been able to go to the Holy Land themselves, but with a detailed map, they could do the next best thing. “When they cast their eyes over Cranach’s map, pausing at Mount Carmel, Nazareth, the River Jordan and Jericho, people were taken on a virtual pilgrimage,” he said. “In their mind's eye, they travelled across the map, encountering the sacred story as they did so.” It must have been transformative for the Renaissance-era readers – and as it turns out, so was its impact on culture in general. An association between divine authority and cartography would have deep ramifications for society. For those reading maps in medieval and earlier times, atlases were often not designed to impart geographical truths as much as they were “religious propaganda,” Meredith Francesca Small, author of the book Here Begins the Dark Sea, told the BBC last year – and even Biblical maps that did exist didn’t really attempt to provide an accurate picture of the land and borders. Instead, they would just divide the region into clear strips of land, MacDonald explained. That wasn’t arbitrary – their cartography was based on the descriptions of Josephus, a Roman-Jewish historian from the first century CE – but it likely reflected more of the author’s various political biases and didactic simplifications than the ever-changing reality on the ground. After all, the Bible itself “doesn’t offer an entirely coherent, consistent picture of what land and cities were occupied by the different tribes,” MacDonald pointed out. “There are several discrepancies.” “The map helped readers to make sense of things even if it wasn’t geographically accurate.” But beginning in the 15th century, and spurred on by the endorsement of thousands of Bibles, the lines on maps stopped being seen as symbolic, and took on an air of definitive truth. Suddenly, we had political borders: “Lines on maps started to symbolise the limits of political sovereignties rather than the boundless divine promises,” MacDonald explained. “This transformed the way that the Bible’s descriptions of geographical space were understood.” It’s an idea that’s somewhat backward from the way we often understand the timeline, he argues. “It has been wrongly assumed that biblical maps followed an early modern instinct to create maps with clearly marked territorial divisions,” he said. “Actually, it was these maps of the Holy Land that led the revolution.” “Early modern notions of the nation were influenced by the Bible, but the interpretation of the sacred text was itself shaped by new political theories that emerged in the early modern period,” he explained. “The Bible was both the agent of change, and its object.” Today, political boundaries probably enjoy more faith than the Bible. But as MacDonald’s paper makes clear, the two concepts have long been intertwined – and we need look no further than the US government’s recent turn to the fundamentalist for proof of that, he noted. “For many people, the Bible remains an important guide to their basic beliefs about nation states and borders,” MacDonald said. “They regard these ideas as biblically authorized and therefore true and right in a fundamental way.” But the truth of both ideas is far more complex and impermanent, he pointed out. “We should be concerned when any group claims that their way of organising society has a divine or religious underpinning,” he cautioned, “because these often simplify and misrepresent ancient texts that are making different kinds of ideological claims in very different political contexts.” The study is published in The Journal of Theological Studies.

Reimagining the Bible, Renaissance-style

The creation of borders

A modern world