-

Feed de notícias

- EXPLORAR

-

Páginas

-

Blogs

-

Fóruns

World-First Fossil Discovery Of Sauropod Stomach Contents Reveals They Didn't Chew Their Food

We’ve Found Sauropod Stomach Contents For The First Time, Revealing They Had Terrible Manners

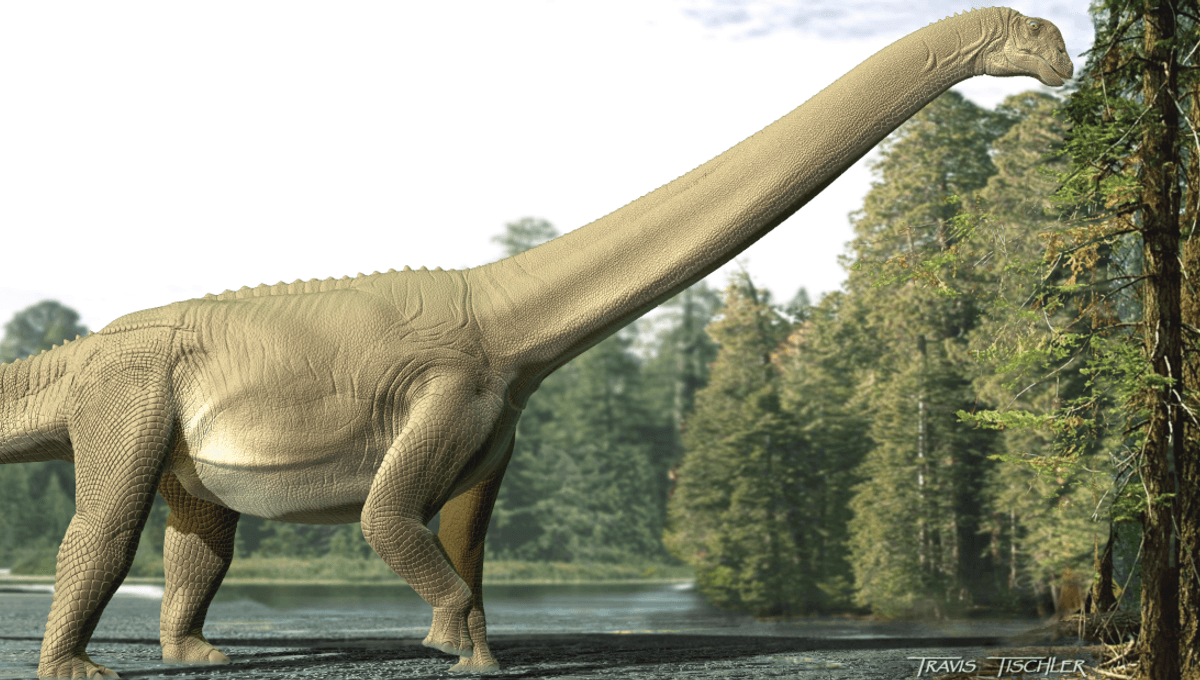

The first ever discovery of sauropod stomach contents has revealed new insights into the dietary habits of these enormous dinosaurs, including support for the long-held idea that they were herbivores. It also appears that they were walking around with “gastric furnaces” that could break down food thanks to fermentation and microbes in the gut – no chewing required.

The fossilized stomach contents were retrieved from a Diamantinasaurus matildae specimen dating back between 94 and 101 million years that was excavated in 2017 by staff and volunteers at the Australian Age of Dinosaurs Museum of Natural History. Sauropods as a group span around 130 million years of time, but this one came from the Winton Formation of Queensland in Australia, home to animals that lived during the mid-Cretaceous. The specimen was a remarkable one, near-complete, but it also came with a mysterious lump of rock. Closer inspection revealed it was a cololite, the fancy name for preserved stomach contents, with multiple layers of plant fossils embedded within it. This marked the first time sauropod stomach contents had been found, which is sort of remarkable for an animal group as well-studied and long-lived (geologically speaking) as sauropods. Inside, they found fossil evidence of conifers, seed-fern fruiting bodies, and angiosperm leaves. It also showed that these animals didn’t really chew their food, instead relying on fermentation and the gut microbiome to break it all down. The amount of heat a sauropod generated through fermentation would have been considerable. Stephen Poropat Today we see this kind of digestion in large-bodied hindgut fermenters like elephants, rhinos, and horses. They’re able to graze on pretty low-quality plant matter all day long and cook it up into something more palatable down in their guts. We know it’s a process that creates heat, so does that mean… “The amount of heat a sauropod generated through fermentation would have been considerable,” said lead author Stephen Poropat of Curtin University to IFLScience. “Having a long neck and tail might have been a way to effectively dump heat (a la the ears of an elephant), and also to keep the brain away from their gastric furnace.” Australian Age of Dinosaurs Collection Manager Mackenzie Enchelmaier holds up sauropod gut content fossil. Not only does this mark a world-first fossil discovery, but it also provides a new perspective on how these enormous dinosaurs with their bulk-eating appetites were shaping the prehistoric environment, not just as adults, but all throughout their lives. “It's often easy to think of prehistoric animals as ‘their biggest adult selves’, but not as babies, juveniles or subadults,” added Poropat. “When you step back and think about it, though, sauropods must have imposed significant pressure on their environment even at a young age.” Sauropods would have been ecosystem engineers throughout their lives, no matter at what level(s) they fed. Stephen Poropat “A horde of hatchlings would have been able to decimate tracts of low-growing plants pretty rapidly. Ravenous 'teenage' sauropods would have ravaged plants both low down, and as high as they could reach. The few of these that made it to adulthood would live to feed at the tops of trees, or continue feeding down low, vacuum-cleaner style (or somewhere in between those two extremes), thereby still putting pressure on their environment.” “The impact that sauropod feeding had on plants in terms of pressuring them to develop defences (either physical or chemical), regrowing rapidly, or encapsulating their seeds in fruits or seed pods to entice or at least enable sauropods to disperse them as they roamed and defecated, is a marvellous subject to ponder. Sauropods would have been ecosystem engineers throughout their lives, no matter at what level(s) they fed.” The study is published in the journal Current Biology.