-

Ροή Δημοσιεύσεων

- ΑΝΑΚΆΛΥΨΕ

-

Σελίδες

-

Blogs

-

Forum

Why Can't You Domesticate All Wild Animals? The Process Relies On 6 Characteristics Few Mammals Possess

Can Any Animal Be Domesticated? A 1959 Experiment Achieved Remarkable Results With “Wild” Foxes

During 2020, I – like many people in lockdown – was desperate for a pet. You can imagine the temptation, then, when a wee mouse voluntarily wandered into my living room day and night. An opportunity? I thought, but I stopped myself. Deep down, I knew all that would happen was I’d end up covered in bites and urine (the mouse’s, not my own).

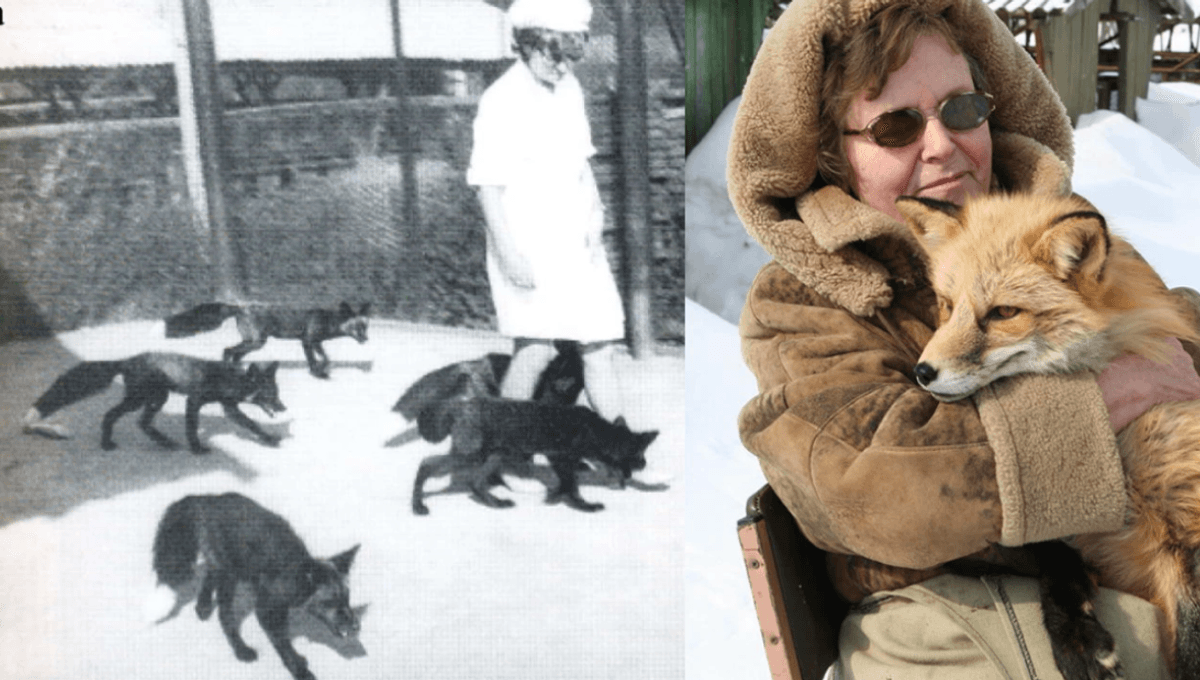

The rest of this article is behind a paywall. Please sign in or subscribe to access the full content. As I write this article five years on, there’s an animal curled up happily on my desk. He has a tail, claws, big teeth – all sounding rather wild, until you note he’s sleeping inside a big fluffy doughnut. So, what is it that separates the animals that will happily live as our companions and those that won’t? There’s more to the process of domestication than simply grabbing a wild animal and keeping it in your house. It's a kind of mutualism that requires two unrelated species to both benefit from each other's company. Wolves became dogs because there was a reciprocal exchange of food, warmth, and protection to be gained. Wild cats became less so when the advent of human settlements and the rodents they attracted made hanging out with us seem like a breezy buffet. Thousands of years on and we find ourselves with the perfect companions that love to play, snuggle, and watch us pick up their poop. However, while cats and dogs are the most famous examples, there was another creature that may have become Homo sapiens’ best friend before either one of them. A 2024 study described how ancient hunter-gatherers in South America may have kept foxes as pets before domestic dogs arrived on the continent. Evidence for this unexpected alliance came from a 1,500-year-old burial site in Patagonia, Argentina, where a human skeleton appeared to have been buried alongside a fox, suggesting that the pair shared a special bond during their lifetimes. The site was originally discovered in 1991 and contained the remains of at least 24 hunter-gatherers and an unidentified canid buried among them. Recent genetic and isotopic analyses revealed the animal to be Dusicyon avus (Or is it D. australis?), an extinct South American fox species that lived until about 500 years ago. Chemical evidence showed the fox ate a largely human-like diet, suggesting it was fed by people and probably kept as a companion or pet, which explains its intentional burial alongside humans. So, could my 2020 pet-stricken self have simply stepped outside and found my new best friend raiding bins on the streets of London? Any attempt would’ve likely ended up with me once again covered in bites and urine, but scientists have achieved the domestication of foxes in the modern era. In 1959, scientists began an experiment to see if it was possible to take the silver fox (a variant of the red fox, Vulpes vulpes) and mold it into a domesticated animal. Unlike the domestication of cats and dogs that happened gradually, the experiment actively selected for tameness and, within 59 years, saw a remarkable transformation. “Starting from what amounted to a population of wild foxes, within six generations (6 years in these foxes, as they reproduce annually), selection for tameness, and tameness alone, produced a subset of foxes that licked the hand of experimenters, could be picked up and petted, whined when humans departed, and wagged their tails when humans approached,” wrote Lee Alan Dugatkin in a 2018 paper about the study. “An astonishingly fast transformation. Early on, the tamest of the foxes made up a small proportion of the foxes in the experiment: today they make up the vast majority.” “Their stress hormone levels by generation 15 were about half the stress hormone (glucocorticoid) levels of wild foxes. Over generations, their adrenal gland became smaller and smaller. Serotonin levels also increased, producing “happier” animals. Over the course of the experiment, researchers also found the domesticated foxes displayed mottled “mutt-like” fur patterns, and they had more juvenilized facial features (shorter, rounder, more dog-like snouts) and body shapes (chunkier, rather than gracile limbs).” As another canid (albeit one in a different genus), it’s not all that surprising that foxes can be domesticated like dogs, but the vast majority of mammal species have never been domesticated. That’s because they don’t meet the characteristics that make a good candidate for domestication. In his book Guns, Germs, And Steel, author and UCLA geography professor Jared Diamond laid out six of these characteristics. They include the capacity to be bred in captivity, a flexible diet (if they’re going to be won over by our scraps), rapid maturation, a docile nature, they must adhere so some kind of social hierarchy, and be resilient. Doesn’t sound much like my house mouse, does it? Sigh. Still, they do make great additions to the London Underground.Domesticating wild animals

The first pet?

The silver fox domestication experiment

Why can’t some animals be domesticated?