-

أخر الأخبار

- استكشف

-

الصفحات

-

المدونات

-

المنتديات

First-Ever View Of The Sun’s Polar Magnetic Field Reveals Major Surprise

First-Ever View Of The Sun’s Polar Magnetic Field Reveals Major Surprise

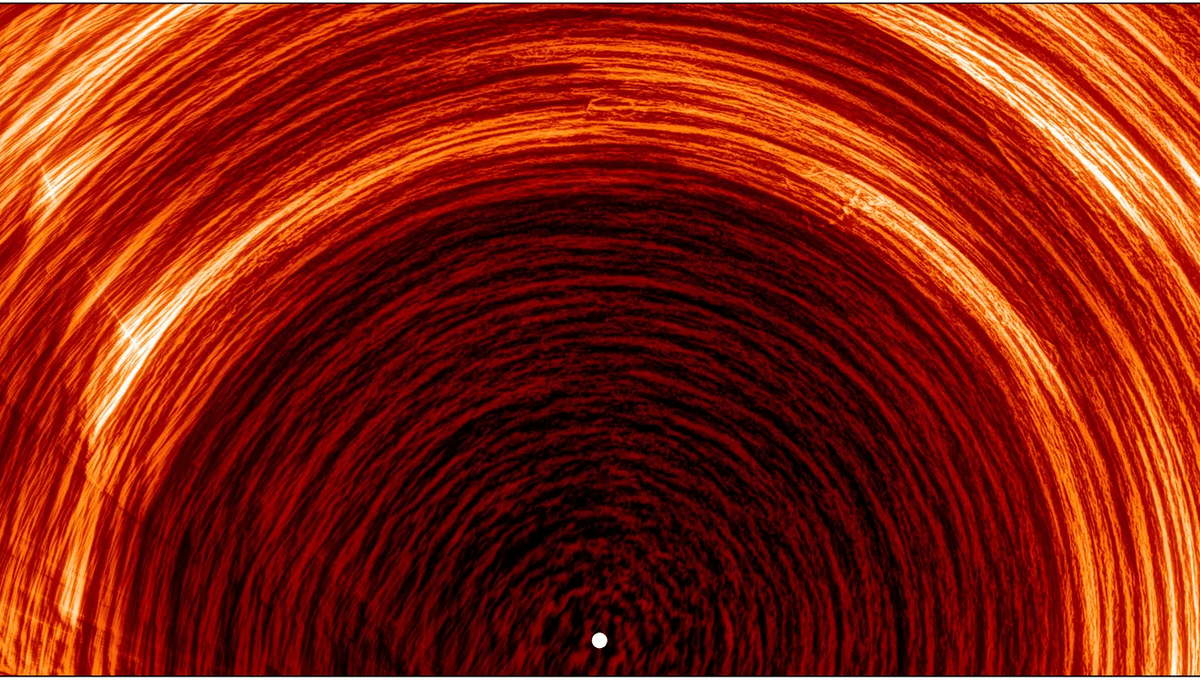

This year, for the first time in history, we got the first image of the polar region of the Sun. The European Space Agency’s Solar Orbiter mission was shifted to an orbit with a tilt compared to the plane of the Solar System, and this has led to the first exciting observations. The first science from that incredible view has now been reported, and there are some significant surprises.

The rest of this article is behind a paywall. Please sign in or subscribe to access the full content. Astronomers have been able to study the magnetic field in the Sun's polar regions for the first time. The magnetic field of the Sun underpins its 11-year-long cycle of activity, and what goes on at the pole is important, even though we have not been able to observe it like this before. The solar magnetic activity is marked by the circulation of plasma in each solar hemisphere. The near-surface plasma drifts from the equator to the poles, and then inside the Sun, it goes back to the poles. The cycle affects the whole hemisphere, and the poles have always been seen as a crucial region for this process. But up until this year, researchers only had a grazing view of what went on. Solar Orbiter has changed that. The orbiter was able to track supergranules, the cells of hot plasma that divide the surface of the Sun. They are two to three times the size of our planet, and due to the convection of the plasma, their horizontal surface pushes the field lines to their edges, creating what we see as the Sun’s magnetic network. Based on the grazing view, the general consensus was that the plasma cells and the magnetic field shifted poleward more slowly than at the equator. But Solar Orbiter has shown that the speed is higher than expected, 10-20 meters per second, almost as fast as at lower latitudes. “The supergranules at the poles act as a kind of tracer. They make the polar component of the Sun's global, eleven-year circulation visible for the first time,” Lakshmi Pradeep Chitta, research group leader at the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research (MPS) and first author of the new study, said in a statement. Understanding the motion of the plasma has revealed important clues about the magnetic field at a global scale. While it is early days, and it is not clear yet whether the Sun's "magnetic conveyor belt" really does slow down at the poles, the new findings show just how crucial Solar Orbiter observations will be to understand the Sun as a whole. “To understand the Sun's magnetic cycle, we still lack knowledge of what happens at the Sun's poles. Solar Orbiter can now provide this missing piece of the puzzle,” added Sami Solanki, MPS Director and co-author. The study is published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.