-

Feed de notícias

- EXPLORAR

-

Páginas

-

Blogs

-

Fóruns

Oldowan Tools Saw Early Humans Through 300,000 Years Of Fire, Drought, And Shifting Climates, New Site Reveals

Oldowan Tools Saw Early Humans Through 300,000 Years Of Fire, Drought, And Shifting Climates, New Site Reveals

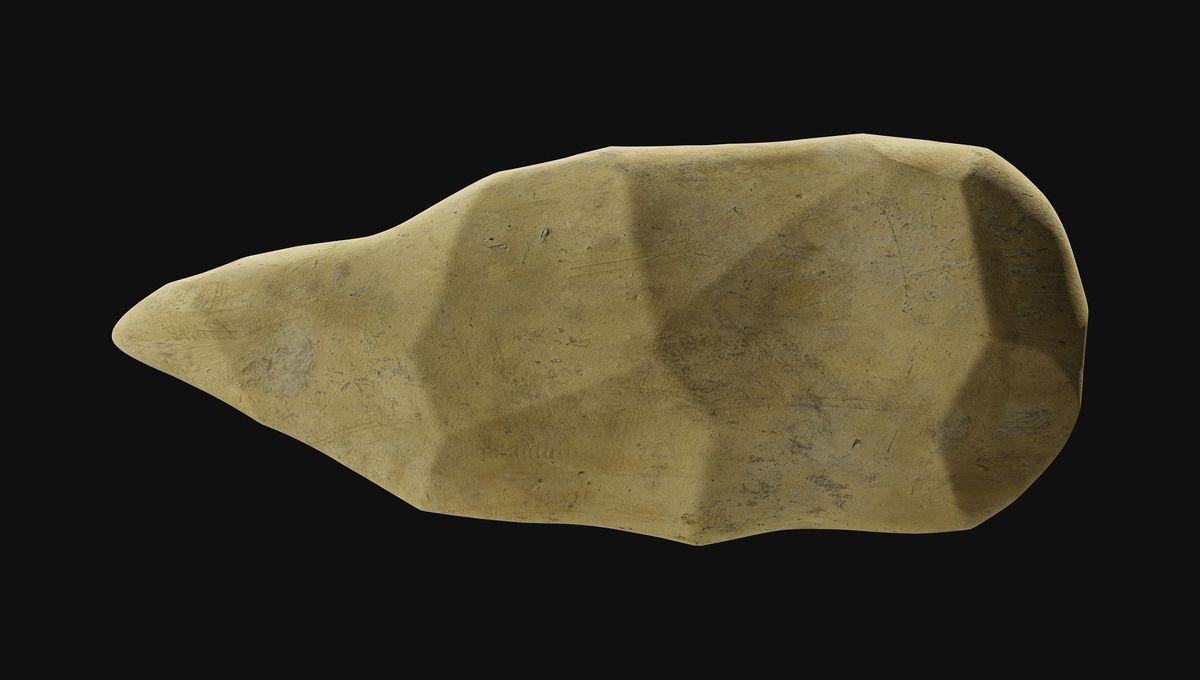

A new site in one of the most important basins for humanity’s evolution has provided evidence of occupation over an unprecedented period. Across 300,000 years, the toolmakers maintained a similar style in the face of a harsh and changing climate, in contrast to places occupied much more briefly.

The rest of this article is behind a paywall. Please sign in or subscribe to access the full content. Millions of years ago, the Turkana Basin in northern Kenya was a center of innovation for our ancestors, or possibly one of the related species known to have lived alongside them. A new archaeological site reinforces its status as one of the first and longest-lasting places for humans to make stone tools. When stone tools were discovered at Lomekwi, on the west bank of Lake Turkana, they pushed back what was thought to be the origins of stone tool-making by about 500,000 years to at least 3.3 million years ago. Although the flakes, cores, and anvils found at Lomekwi mark the first evidence of deliberate tool-shaping, the later Oldowan toolkit proved superior and more lasting. The two styles may have been made by different species. Named after a gorge almost 1,000 kilometers to the south of Lake Turkana, Oldowan tools have been found at many sites across East Africa. Now we have evidence that Oldowan-style toolmakers not only lived in the Lake Turkana Basin, but persisted there. The site is known as Namorotukunan and lies on the opposite side of the lake from Lomekwi. Oldowan tools found there have been dated from 2.75 to 2.44 million years ago, almost 800,000 years before the original Olduvai site. Earlier examples of the Oldowan toolkit have been found at Nyayanga, well to the south, but the authors of a report on the discovery note, “Oldowan sites older than 2.6 million years ago are rare.” Very ancient Oldowan finds represent a narrow window of time at other sites, possibly indicating environmental shifts made locations undesirable. The persistence of the tool-makers at Namorotukunan then is exceptional, since conditions changed a lot between the times we know people were there. “This site reveals an extraordinary story of cultural continuity,” said Professor David Braun, of George Washington University, in a statement. “What we’re seeing isn’t a one-off innovation—it’s a long-standing technological tradition.” Remains of plants found at the site indicate considerable climatic variability. Rainfall had fallen by almost two-thirds in the 100,000 or so years prior to 2.75 million years ago, when the first tools were deposited, creating a harsh desert environment. Conditions were wetter by the time the last Oldowan tools found at the site were made, but the climate would still have been semi-arid. “Namorotukunan offers a rare lens on a changing world long gone—rivers on the move, fires tearing through, aridity closing in—and the tools, unwavering. For approximately 300,000 years, the same craft endures—perhaps revealing the roots of one of our oldest habits: using technology to steady ourselves against change,” said Dr Dan Paclu Rolier of the University of São Paulo. Three excavations produced a total of 1,290 stone tools and bones, many of the latter showing signs of being butchered with the former. The tools show a similar understanding of fracture dynamics to those at other Oldowan sites, the authors report, with crypto-crystalline rocks such as jasper preferred over the more common basalt. However, certain advanced techniques found at younger Oldowan sites are absent. When the first tools were deposited, there Namorotukunan lay on a river system with a flow strong enough to transport cobbles, while also offering quieter pools. In the surrounding near-desert, it must have seemed a paradise. “The plant fossil record tells an incredible story: The landscape shifted from lush wetlands to dry, fire-swept grasslands and semideserts,” said Dr Rahab Kinyanjui of the National Museums of Kenya. “As vegetation shifted, the toolmaking remained steady. This is resilience.” Today, conditions are harsher still, with the lake barely drinkable and salinity expected to worsen from a major dam on its major water source. Nevertheless, the attraction has not ended. Despite the small current population, humanity has been drawn back, engaging in one of our most ambitious engineering projects of recent times in the form of a wind farm south of Namorotukunan. The study is published in Nature Communications.