-

Feed de Notícias

- EXPLORAR

-

Páginas

-

Blogs

-

Fóruns

A "Super-Earth" In The Habitable Zone Is Half The Distance To Comparable Worlds

A "Super-Earth" In The Habitable Zone Is Half The Distance To Comparable Worlds

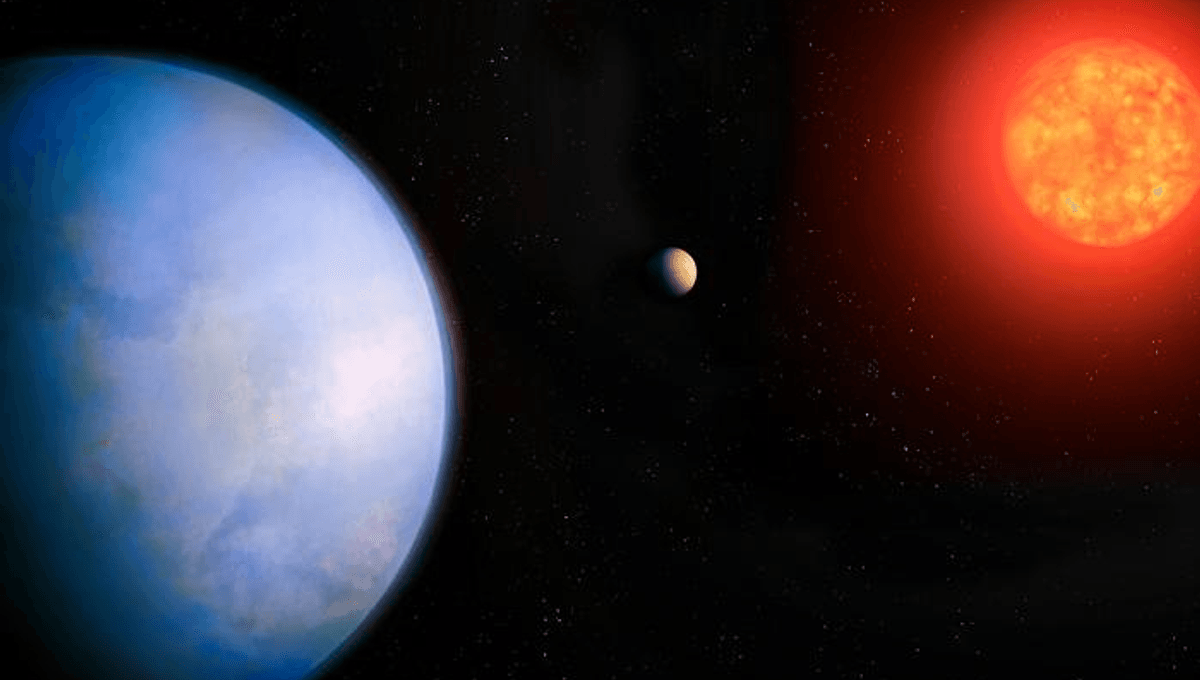

A newly discovered planet sits in the habitable zone of its star, where temperatures are right for liquid water if the atmosphere is appropriate. Based on the available data, GJ 251c is thought most likely to be a “super-Earth”, a rocky planet somewhat larger and more massive than Earth, but a sub-Neptune can’t be entirely ruled out. Best of all, it’s less than 20 light-years away, offering better prospects for telescope observations than a number of previous favored targets that are mostly 40 light-years away at least.

The rest of this article is behind a paywall. Please sign in or subscribe to access the full content. Humanity recently passed the 6,000 mark for planets discovered around other stars. While this has been great for the insights provided into population dynamics, most of these are far too hot to be prospects to host life, and the exceptions are more often gas giants than rocky worlds. That’s meant a handful of planets have got most of the attention, including TRAPPIST-1e and LHS 1140b, dubbed “the best place to look for life beyond the Solar System". Now, a new name is likely to be added to that list, GJ 251c. "We look for these types of planets because they are our best chance at finding life elsewhere,” said Professor Suvrath Mahadevan of Penn State University in a statement. “The exoplanet is in the habitable or the ‘Goldilocks Zone,’ the right distance from its star that liquid water could exist on its surface, if it has the right atmosphere." GJ 251c has an orbit lasting 53.6 Earth days, and it's at least 3.8 times the Earth’s mass. With an atmosphere similar to Earth’s, it would be cold enough to be totally ice-bound, but a thick atmosphere – consistent with its greater mass – dominated by carbon dioxide and water vapor would create quite steamy conditions. The planets we have found in the GJ 251 system don’t appear to pass between their star and us, so space telescopes like Kepler and TESS can’t detect them through regular dimming of the star. Instead, GJ 251b was found five years ago through the older radial velocity technique, detecting the way the star moves towards and away from us from its blue or red shift as the gravity of its planets induces subtle movements. Now, a second planet has been found, at a more inviting temperature. GJ 251b is massive enough and close enough to its star to make an easily detectable wobble, particularly in a smallish star close to home. However, the signal of its influence made it even harder to find anything of similar size further out. Undeterred, Mahadevan and colleagues combined data from five telescopes over the last 20 years to make our understanding of GJ 251b’s contribution more precise, so it could be subtracted out and subtler effects could be seen. Then they had to clean the data of distortions produced by starspots and related activity. Having identified suspected signals in the noise at 54, 68, and 73 days, they applied the near-infrared spectrograph at the McDonald Observatory, Texas, which measures variations in the locations of spectral lines just beyond our capacity to see. This satisfied the team that the day 54 signal was from a planet, while the others were illusionary or had less interesting causes. “This discovery represents one of the best candidates in the search for atmospheric signature of life elsewhere in the next five to ten years,” Mahadevan said. This is a lot of work to go to, and the fact that GJ 251c does not transit means we won’t get the reward of studying its atmosphere, if it has one, when starlight shines through. On the other hand, at just 20 light-years away, this really is our galactic neighborhood, and the next generation of telescopes may be able to image it directly. Indeed, the authors write, “GJ 251c is currently the best candidate for terrestrial, [habitable zone] planet imaging in the Northern Sky.” Proxima Centauri b, the closest habitable zone planet, never gets high enough to see clearly from most of the Northern Hemisphere. Moreover, most of the rocky planets we have found orbit very dim stars, so to be in the habitable zone they must be very close to their star, making them hard to spot. GJ 251 is still an M-dwarf, but brighter and at 0.35 solar masses more massive than all but one of the closer stars known to host planets. Consequently, its habitable zone is further out than popular targets like Proxima Centauri or TRAPPIST-1. That puts more distance between star and planet for telescopes to work with, and also means worlds in the zone are less vulnerable to flares of the sort thought likely to have stripped Proxima b of its atmosphere. “While we can’t yet confirm the presence of an atmosphere or life on GJ 251c, the planet represents a promising target for future exploration,” Mahadevan said. “We made an exciting discovery, but there's still much more to learn about this planet.” The study is open access in The Astronomical Journal.