-

Fil d’actualités

- EXPLORER

-

Pages

-

Blogs

-

Forums

JWST Captures Best Image Yet Of A Supergiant Star Before It Went Supernova

JWST Captures Best Image Yet Of A Supergiant Star Before It Went Supernova

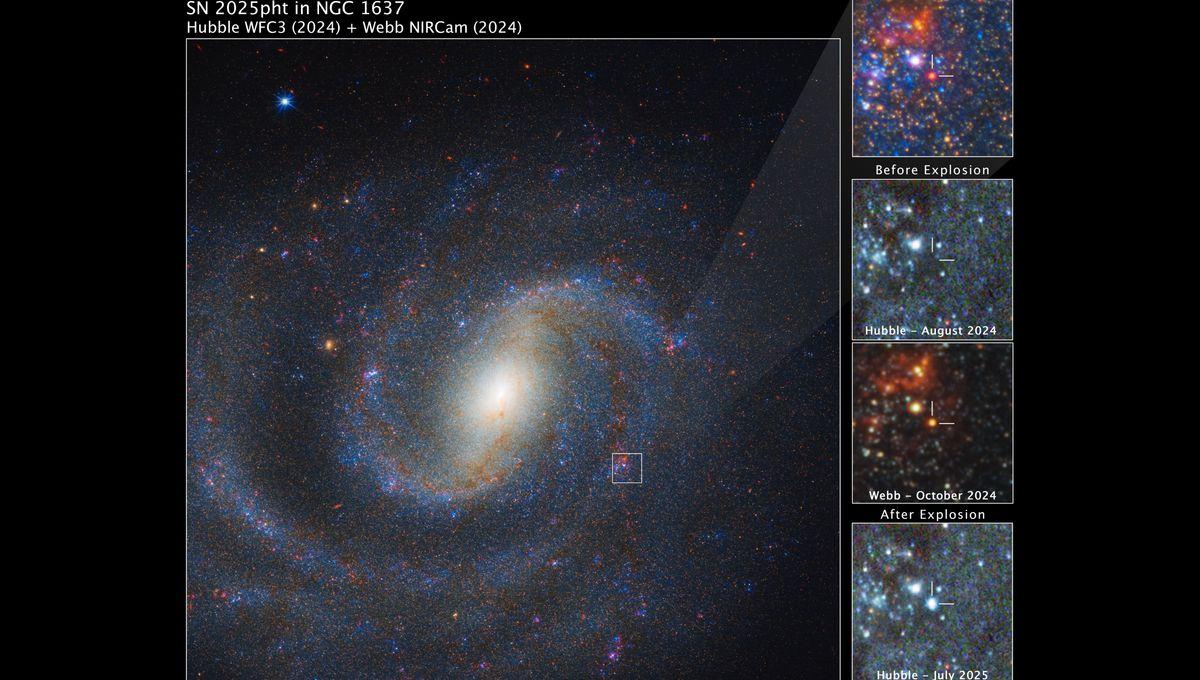

Images taken by JWST reveal the star that became SN2025pht before it exploded, providing our best view of a red supergiant proto-supernova. The cloud of dust hiding the star from our eyes may answer the question of why we haven’t seen more.

The rest of this article is behind a paywall. Please sign in or subscribe to access the full content. SN2025pht was spotted on June 29 this year. Its location, 40 million light-years away in the galaxy NGC 1637, makes it one of the closer supernovae of recent times, but there have been a few twice as close. More significantly, because NGC 1637 is a relatively nearby galaxy, it had drawn the attention of JWST twice before the explosion. This allowed astronomers to scour images from before the event to identify the star responsible and see it in detail we have not seen before, at least for this type of star. Supernovae have two main origins: the collapse of giant stars and white dwarfs exceeding the mass limit of 1.44 times the Sun. Within those, however, are more subtle differences, in particular the type of giant star that undergoes core collapse. Red supergiants should be the most common source of these events, which is why there is so much focus on Betelgeuse. However, since we have developed the capacity to see supernovae in galaxies distant enough to provide a large sample size, the picture has looked wrong. “For multiple decades, we have been trying to determine exactly what the explosions of red supergiant stars look like,” said Dr Charlie Kilpatrick of Northwestern University in a statement. “Only now, with JWST, do we finally have the quality of data and infrared observations that allow us to say precisely the exact type of red supergiant that exploded and what its immediate environment looked like. We’ve been waiting for this to happen — for a supernova to explode in a galaxy that JWST had already observed. We combined Hubble and JWST data sets to completely characterize this star for the first time.” For most stars, the red giant phase is the last of their life, after their core has run out of hydrogen to fuse. More massive stars become red supergiants, and if they started out with a mass greater than about eight times the Sun's, they should go out with a bang. Sometimes supernovae come from other star types, such as the blue supergiant Sanduleak that became SN 1987A, the most recent supernova in the local group of galaxies, but modeling suggests red supergiants should still be the main source. In the more than 30 cases where a progenitor star has been found, most have indeed been red supergiants. Nevertheless, we have detected fewer examples than expected, and they have generally been surprisingly faint, creating what has been known as the “red supergiant problem”. SN2025pht may explain that. The JWST images show an exceptionally thick shroud of dust around it, one that blocked more than 99 percent of the visible light of a star some 100,000 times more luminous than the Sun. It’s only because infrared radiation, which the JWST collects, is less susceptible to dust than visible light that JWST could see it. “It’s the reddest, dustiest red supergiant that we’ve seen explode as a supernova,” said study coauthor and graduate student Aswin Suresh. The findings have led the authors to reevaluate previous supernovae, seen in galaxies that had been observed by Hubble or ground-based telescopes in visible light. “Previous explosions might have been much more luminous than we thought because we didn’t have the same quality of infrared data that JWST can now provide,” Kirkpatrick said. Meanwhile, if dust is a regular feature of the space around red giants shortly before their last hurrah, we might not have been able to see pre-explosion stars at all in galaxies JWST never examined. That’s particularly the case for those explosions that were further away. Although the extent of SN2025pht’s dust was unexpected, some astronomers had thought dust might be a factor in the failure to find red supergiant stars at the spots where supernovae would subsequently explode. We know this type of star can puff out a lot of gas that can obscure our view of them – anyone who looked at Betelgeuse in 2019-2020 saw the effect in action. “I’ve been arguing in favor of that interpretation, but even I didn’t expect to see such an extreme example as SN2025pht,” Kilpatrick said. “It would explain why these more massive supergiants are missing because they tend to be dustier.” Dust can come in many forms, and the authors were surprised at how rich in carbon in the NGC 1637 star’s vicinity was, in contrast to the silicate dust we usually see around red supergiants. The planned Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope will give astronomers an even better look at stars like this, potentially observing their variability when, like Betelgeuse, they dim as a result of dusty sneezes. “With the launch of JWST and upcoming Roman launch, this is an exciting time to study massive stars and supernova progenitors,” Kilpatrick said. “The quality of data and new findings we will make will exceed anything observed in the past 30 years.” Another interesting aspect of the work is that the progenitor star was equally bright both times JWST looked at NGC 1637, despite months passing between. It’s possible this was coincidental, and it had greatly brightened or dimmed in between before reverting, but the finding also suggests potential supernovae might not give us much warning. The study is published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.