-

Feed de Notícias

- EXPLORAR

-

Páginas

-

Blogs

-

Fóruns

In 2013, A Volcanic Eruption Wiped Out Life On This Remote Island. Then, Somehow, Plants Reemerged

In 2013, A Volcanic Eruption Wiped Out Life On This Remote Island. Then, Somehow, Plants Reemerged

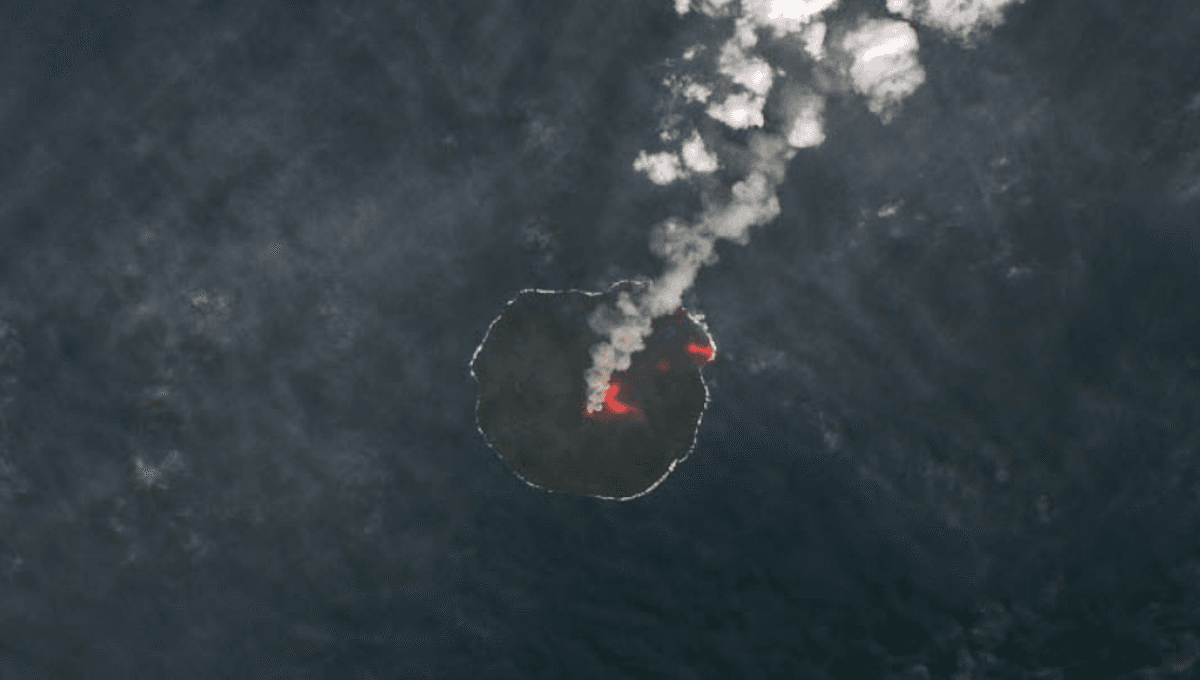

Twelve years ago, a volcanic eruption almost totally wiped out life on an island in the Pacific. Now, in the wake of the devastation, scientists are using genetic analysis to see how flora managed to bounce back on the scarred island.

The rest of this article is behind a paywall. Please sign in or subscribe to access the full content. Nishinoshima, a volcanic island around 1,000 kilometers (620 miles) south of the Japanese capital Tokyo, has seen a handful of eruptions since recording began in the early 1970s. One of the most momentous events started in November 2013 when lava began erupting out of a vent on the seafloor just southeast of the island. As the molten rock cooled and solidified, it formed a tiny new island that eventually engulfed the original landmass with fresh loads of lava. Throughout this turmoil, red-hot lava and blankets of ash buried much of the land surface, killing virtually all fauna on the island. Somehow, against the odds, plant life managed to return without the aid of humans. In 2019, scientists at Tokyo Metropolitan University recovered samples of common purslane (Portulaca oleracea) from Nishinoshima, just before another eruption wiped the slate clean again. In a new study, the team has studied the plant’s DNA to find out how it recolonized the volcanic island after near-total devastation. They found the plants were closely related to populations found in nearby Chichijima, another volcanic island. But the Nishinoshima plants weren’t identical to their neighbours. They had undergone a sudden loss of genetic variation, a common effect seen when a new colony is started by a small number of individuals from a larger, original population. This so-called “founder effect” means that from a handful of seeds that arrived on the island and an entire new lineage of plants began to take root on the scorched landscape. Another mystery is how the seeds reached Nishinoshima in the first place. The researchers note that they are barely bigger than a poppy seed and shaped like tiny disks, making them perfectly built for travel. They’re buoyant enough to ride ocean currents, light enough to be carried on the wind, and small enough to be eaten by a bird. However, you never know what the future holds on volcanically active islands. With eruptions continuing to reshape Nishinoshima, the future of its fragile new ecosystem remains as unpredictable as the landmass itself. The new study is published in the journal Plant Systematics and Evolution.