-

Web sayfası bildirimcisi

- EXPLORE

-

Sayfalar

-

Blogs

-

Forums

Hayabusa2's Target Asteroid Is 4 Times Smaller Than Thought – Can It Still Touch Down On It?

Hayabusa2's Target Asteroid Is 4 Times Smaller Than Thought – Can It Still Touch Down On It?

After the successful collection of material from asteroid Ryugu, Hayabusa2 flew back to Earth to drop it off. But the spacecraft's journey is not ending there. It is now traveling to perform a high-speed flyby of asteroid Torifune next July, and in 2031 will rendezvous with asteroid 1998 KY26. When this target was selected, it was going to be the smallest object ever to be encountered by a spacecraft. It turns out it is a lot smaller than previously thought.

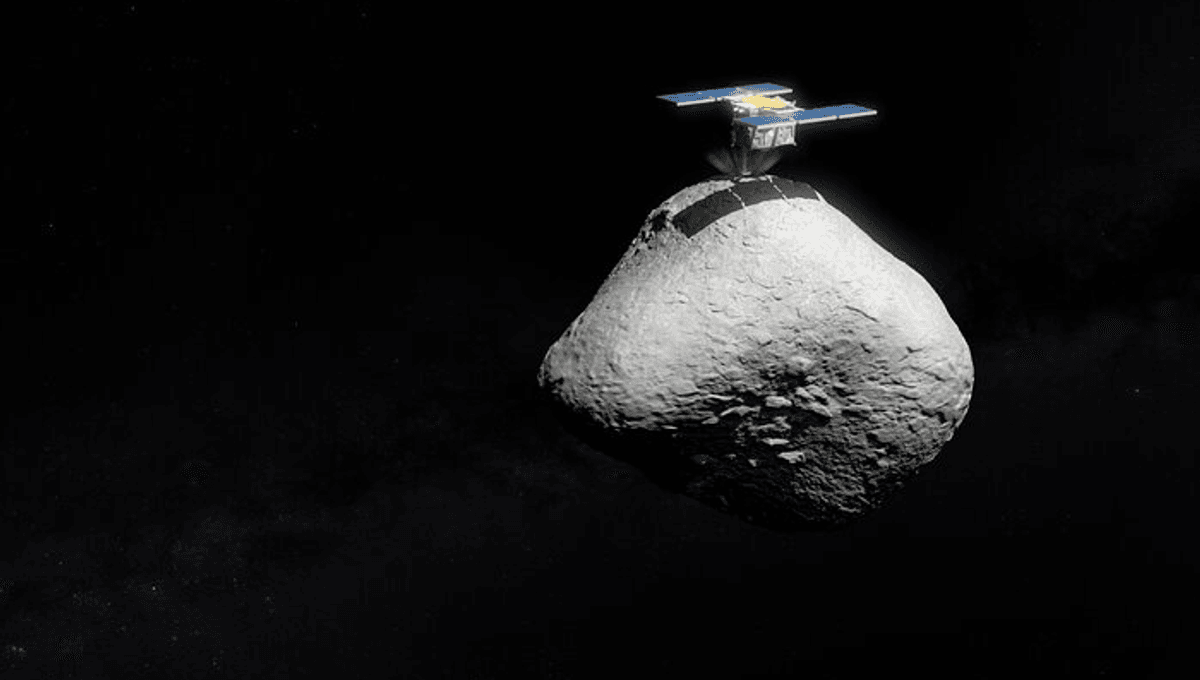

The rest of this article is behind a paywall. Please sign in or subscribe to access the full content. Estimating the size of asteroids is difficult. Asteroids are mostly discovered in visible light, so based on the light reflected and the space rock's distance, you can give a range. Crucial to that is guessing the right type of asteroid; carbonaceous asteroids are different from stony, and both are different from metallic. Each type and its subclasses can reflect light differently. The final target of Hayabusa2 is itty bitty! Image credit: ESO/M. Kornmesser. Asteroid models: T. Santana-Ros, JAXA/University of Aizu/Kobe University It is not surprising that 1998 KY26 was overestimated. Observations almost three decades ago place it as being a nearly spherical, 30 meters (100 feet) across, and rotating in just over 10 minutes. The Japanese Space Agency (JAXA) mission needed to have the most accurate data on the object. In 2024, ground-based telescopes had the last opportunity to do those kinds of high-level observations, and a team used the Very Large Telescope from the European Southern Observatory. What they revealed was a significantly different object. They need to reconsider what they can do and what they cannot do with this object. Dr Toni Santana-Ros “We were expecting basically to just observe the object and confirm the results that were published in 1999,” lead author Dr Toni Santana-Ros, a planetary scientist at the University of Alicante and University of Barcelona, told IFLScience. “We're surprised to discover that the object looks completely different from what was expected; it was much smaller, three/four times smaller than expected. It's spinning faster, twice as fast. And also the composition itself… It's much brighter.” The asteroid is believed to be now 11 meters (36 feet) across, spinning on its axis every five minutes, and has a peculiar composition. The discovery has massive implications for the mission. One of the possibilities is that Hayabusa2 would try to touch this asteroid. It is unclear if that can be done. “They need to reconsider what they can do and what they cannot do with this object,” Dr Santana-Ros explained. “The funny thing is that the object is about 11 meters in diameter, and the spacecraft itself is 6 meters [20 feet]. So it's more than half of the object it’s going to visit. It's quite a funny thing!” This small asteroid gets close to Earth every few years, but it is so small and the next passage is so far away that it will be too dim to be seen by any ground-based telescopes. JWST might be able to characterize the object more, just like it did for the asteroid 2024 YR4, which has a chance of hitting the Moon in a few years. A lot is happening when it comes to asteroid research globally, which also impacts priorities for the large observatories. “Ten years ago, I was defending my PhD using a 40-centimeter-sized [16-inch] telescope,” said Dr Santana-Ros. “And now I'm using, we are using the largest telescope in the world! It was really exciting and amazing!” There are still unknowns about this object. Researchers are not sure if it's a single rock or a rock pile. If it's just gravel held together, the gravity of the object will be tiny, and a touchdown might be very dangerous for Hayabusa2, as it might easily disrupt it. That was the risk for the OSIRIS-REx touchdown of Bennu, and Bennu is a lot larger. The study is published in the journal Nature Communications.