Frederic Lewis/Getty Images

Take a look through your recipe cards. No, not the digital ones. The handwritten recipes on 3x5-inch index cards. Maybe you'll find that recipe that uses Lipton's Onion Soup Mix to make fondue. Would that be a good one for this Saturday's fondue party? It'll be a night of good food and good company — and good luck not dropping your bread bit into the steaming pot of cheese.

We're ready to wax nostalgic about old-school food traditions that once filled kitchens and social calendars. This is a chance to appreciate wartime canning that preserved the harvests of Victory Gardens. And a chance to tip our hats to hosts of Tupperware parties, who taught a generation the essential skill of container burping. We'll thank the milkman and think a lot about gelatin molds instead of charcuterie boards. So, grab a seat and a cup of percolated coffee and join us as we explore some food customs of yore.

1. Having a utensil for everything

Fpg/Getty Images

The history of eating with utensils is complicated. Unsurprisingly, it's tied to wealth, class, and a whole lot of showing off. Some Victorians, for example, flaunted social standing with elaborate collections of silverware. Not just fancy swirly patterns, but hundreds of utensils with very specific purposes. Coffee spoons were smaller than tea spoons. Sorbet spoons differed from ice cream forks and all the other forks like strawberry, snail, sardine. The lists went on and on, crossing the Atlantic and growing in America into the 20th century.

By 1926, the U.S. Department of Commerce decided enough was enough. They issued Simplified Practice Recommendation No. 54 to cap sterling silver sets at 57 pieces. This voluntary industry agreement was mostly followed but still left America with plenty of spoons. The document included basic tea, dessert, table, and soup spoons; fancier bouillon, coffee, iced tea, and grapefruit spoons; and single serving spoons for bonbons, olives, berries, preserves, and sugar — and that was just the spoons.

Over the years, many of these ultra-specific pieces quietly slipped off the table. Some lingered or staged comebacks, like the grapefruit spoon in the 1970s. But nowadays, most of us stir coffee with any ole teaspoon, spear strawberries with a regular fork, and, if we even own a grapefruit spoon, probably use it to scoop out an avocado. Victorians might be banging their marrow spoons in horror, but we seem OK without a spoon just for bone goo.

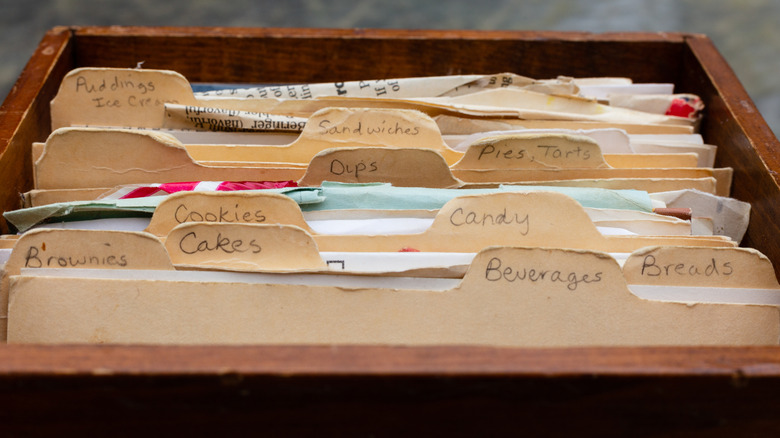

2. Writing and keeping recipe cards

Patrish Jackson/Shutterstock

Once upon a time, every home cook's most prized possession wasn't a fancy stand mixer or an air fryer — it was a simple stack of 3x5-inch index cards. Those little cards that were tucked neatly into a recipe box, held culinary traditions, like the family's go-to birthday cake, a must-have Thanksgiving pie, and maybe even that casserole nobody liked but everyone politely ate anyway. The cards were time capsules covered in gravy splatters, dotted with frosting fingerprints, and often stuffed alongside photos, grocery lists, or quick notes that read something like "Don't forget extra nutmeg!"

Many of these recipes were handwritten treasures, but others were preprinted. From the 1930s through the 1990s, magazines offered recipe subscriptions, sending out recipe cards to help readers expand their collections. Of course, advertisers were quick to use the idea to promote products. Really, how could you make Jell-O salad without Jell-O? Cards made it easy to tuck brand names right into your personal recipe box.

These days, instead of a recipe box, we're more likely to turn to a food blog, TikTok video, or recipe app. The recipe card is still around, but in digital form. Paper just can't compete with the infinite scroll.

3. Hosting fondue parties

H. Armstrong Roberts/classicstock/Getty Images

Cheese fondue melted Americans' hearts when it was showcased at the 1964 World's Fair in New York. What followed was a decades-long love affair of dipping hunks of bread (or really anything that could balance on a long fork) into a bubbling pot of cheese. The "fondue party" era was born, with stores selling party kits and premade mixes so anyone could host their own cheesy gathering.

Cookbooks and magazines piled on recipes, popular TV shows like Julia Child's "The French Chef" stirred up the fondue pot, and advertisers happily jumped aboard. In the late '60s, Lipton pitched its Onion Soup Mix as the secret to an easy Lipton Fondue American recipe, while the 1970s saw Van Camp's advertise its Pork and Beans with a Franktastic Fondue recipe.

By the time the Franktastic Fondue recipe was circulating, sleek electric models challenged the traditional flame-heated fondue pots. The new plug-in versions promised to keep your cheese at the perfect temperature and made it easy to bring the party into the living room or out on the patio. No matter the location, fondue parties often came with playful etiquette. Drop your bread in the pot twice, congratulations — you just volunteered to host the next fondue night. But maybe not enough people dropped their bread pieces, because by the '80s and '90s, the fondue party craze had cooled. Electric pots were relegated to the back of the cupboard and everyone seemed to lose their appetite for cheese-coated pork-and-bean experiments.

4. Making a holiday fruitcake

Gkrphoto/Getty Images

Back in the day, Johnny Carson got a lot of mileage out of fruitcake jokes on "The Tonight Show." He suggested there's only one fruitcake in the world that just gets regifted every Christmas. For decades, fruitcake has been the punchline of the holiday season. But that wasn't always the case.

Fruitcake is deeply rooted in American culture. Martha Washington, the former first lady, had a famous Great Cake recipe. Essentially, it was a dense fruitcake soaked in brandy and filled with dried fruit and nuts. It became a White House holiday tradition, with some administrations baking hundreds of cakes to share with guests. According to former White House executive chef Henry Haller, every president he served had fruitcake on the holiday table. That included Gerald Ford, whose family enjoyed giving homemade fruitcakes as gifts. Ford held office in the 1970s. It's proof that, even into the '70s, fruitcake was a dessert fit for a president.

But it wasn't just the political elite who embraced homemade fruitcake as a holiday tradition. The Los Angeles Times called it a "holiday must" in 1953. Life magazine featured fruitcake in a full-color spread in 1961, promising it would "provide a generous welcome for guests." But times change — in 1989, a MasterCard survey found fruitcake topped the list of least-wanted Christmas presents. Artisanal cookies and fancy chocolates may have pushed aside fruitcake. But that immortal labor of love is still out there somewhere, patiently waiting for its comeback.

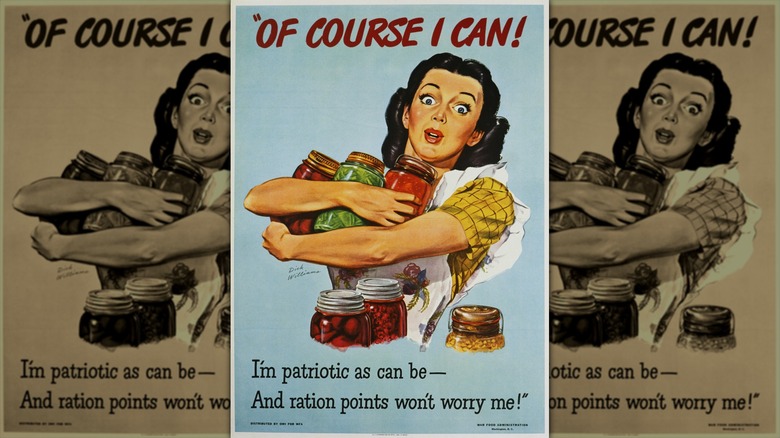

5. Canning and preserving at home

David Pollack/Getty

America knew how to meal prep in 1943. That year, at the height of World War II, home canning was at its absolute peak. Billions of jars and cans were processed. People canned home-raised meats like rabbit and chicken, along with a wide variety of fruits and vegetables — everything from apples and asparagus to peaches and peas.

The government promoted "Victory Gardens" and preservation as patriotic. People grew produce and took up pickling, dehydrating, and canning. Pamphlets and classes showed Americans how to transform backyard and community harvests into neatly stacked rows of jars that could outlast the season (and maybe even survive the apocalypse).

But after the war ended in 1945, home canning started slipping out of fashion. Refrigerators became more affordable, grocery stores filled up, and frankly, people were ready to spend less time boiling jars in sweltering kitchens. The movement got a brief second wind with improved pressure canners and a do-it-yourself movement in the 1970s. Today, some people still keep the tradition alive, though now it's more about small-batch jams and Instagram-worthy pickle jars than wartime survival.

6. Dining in supper clubs

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Baraboo Supper Club in Boise defines a supper club as simply: "A social dining establishment where people come together for good food and a good time." So, how does that differ from a restaurant? The answer might be drowning in booze. Back in the Prohibition era, speakeasies popped up as hush-hush spots to snag an illegal drink. When alcohol was legal again in the early 1930s, many of those speakeasies traded secrecy for supper. They evolved into places where you could linger over dinner, sip a cocktail (legally), and enjoy some live music.

Unlike a high-paced restaurant focused on fast turnover, supper clubs are all about slowing down. Imagine dim lighting, a fixed or limited multicourse meal, and maybe a piano tinkling away in the background. For many supper clubs, community and connection are just as important as the food. Though they're found in big cities, supper clubs have humble Midwest origins. They're tucked away on the edge of town and in rural areas of Wisconsin, Minnesota, Ohio, Michigan, Illinois, and Iowa.

Supper clubs thrived through the mid-20th century. Then along came fast food drive-thrus and casual dining chains, and suddenly the slow, lingering supper fell out of fashion. But they're far from extinct. If you're looking for a taste of nostalgia paired with a cocktail, a supper club is a good bet. Just don't expect any Instagram-worthy photos with the supper club's infamous dim lighting.

7. Celebrating with gelatin salads

ArtbyPixel/Shutterstock

The year 1904 was a wobbly one. Jell-O's popularity exploded as it adopted the slogan "America's Most Famous Dessert." That same year, Knox Gelatine held a recipe contest, where Perfection Salad snagged third place. Perfection, it turns out, was defined as shredded cabbage, celery chunks, and pimentos suspended in a lemony-vinegary gelatin mold. To top it off, drizzle on mayonnaise. What a delicious start to the century!

By mid-century, Knox's unflavored gelatin was still wobbling along (and still is), but the popularity of Jell-O took over. Cooks even used this pre-sweetened concoction in savory recipes — just swap lemon juice for Lemon Jell-O. And yup, that hack worked for Perfection Salad. It also worked for Jellied Potato Salad and the ever-questionable Savory Vegetable Salad Mold (featuring lima beans, celery, and onion). On the sweeter side, people whipped up Jewel-Top Jell-O (that's Jell-O topped with — wait for it — more Jell-O) or the Crown Jewel Pie, which looked like a stained-glass window you could eat.

For a solid few decades, potlucks weren't complete without at least one quivering gelatin mold on the table. Thanksgiving spreads often included a mysterious "salad" that was part dessert, part side dish, and fully confusing. But over the years, America's Jell-O obsession declined. These days, Jell-O salad features prominently on the list of old-school salads no one makes anymore. But Lemon Jell-O is still widely available. So, if you're feeling creative, you can keep the tradition of wiggly salads alive. Just don't forget the mayonnaise garnish.

8. Cooking with lard

Liudmila Chernetska/Getty Images

People have cooked with lard for thousands of years. It used to be an American pantry staple for frying eggs, baking cakes, and larding meat. And it's famous for making perfectly flaky pie crusts. But somewhere along the way, people stopped buying lard. There was one large can-sized culprit: Crisco.

Procter & Gamble's launch of Crisco was a masterclass in early 20th-century marketing. At a time when the public was still grossed out by Upton Sinclair's "The Jungle" (a fictional but all-too-real depiction of the meat-packing industry), Crisco came in looking pure and clean. "The stomach welcomes Crisco," was one slogan. The company described the product as "purely vegetable." Never mind that nobody really knew what was actually in it. It was white, odorless, tasteless, and shelf-stable. It had no horrors of "The Jungle." Crisco sold like hotcakes — and people were now frying their hotcakes in Crisco.

By the 1950s, things got even worse for poor lard. Scientists expressed concerns about saturated fat. Suddenly, lard was being talked about like it had personally clogged every artery in America. But the plot thickened (kind of like gravy made with lard) when newer research suggested that saturated fats might not be quite as villainous as once believed, at least in moderation. Add to that a growing interest in natural fats and food regulations that have helped "The Jungle" situation, and lard may be poised for a comeback. Sometimes food trends come full circle, much like a perfectly flaky pie crust.

9. Hosting Tupperware parties

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Tupperware became so well-known that its name slipped into generic use, like how we say "Band-Aid" for any adhesive bandage. The plastic containers with snug lids first appeared in the 1940s, thanks to inventor Earl Tupper. But unlike the leftovers they were meant to preserve, Tupperware sales went stale. Instead of sealing the deal, the lids were part of the problem. Tupperware containers had to be "burped" to close properly, but customers didn't get the memo. Many thought the lids didn't fit right and returned them in frustration. So, Tupperware reinvented its sales strategy. Forget about department stores, it was time to party!

Tupperware parties were part sales pitch, part social event. Hosts invited neighbors and friends over, set out snacks, and showed off Tupperware's durability by tossing containers across the living room. Guests learned the fine art of the Tupperware burp, order forms made the rounds, and the host earned a cut of the sales. While the image was often suburban housewives leading the charge, all types of people turned the business of selling plastic containers into a serious side hustle.

Tupperware parties surged during the 1950s and 1960s. The sales strategy lingered for decades, but competition and growing health and environmental concerns about plastic meant the party was dying out. Tupperware filed for bankruptcy in 2024 and the brand was acquired by Party Products. At least for now, Tupperware continues to limp along. But most people don't bother with Tupperware parties anymore.

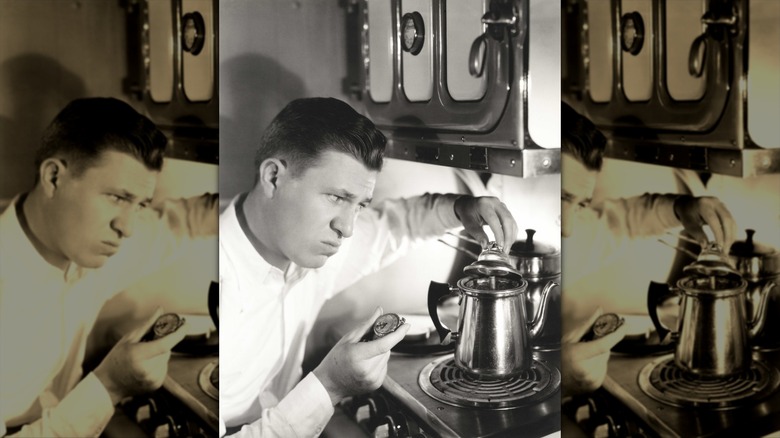

10. Brewing coffee with a percolator

Everett Collection/Shutterstock

Through the 1960s, if you wanted coffee at home, chances are you fired up a percolator. These came in stovetop and electric versions, and they could make a whole pot of Joe big enough to keep the neighborhood buzzing. Unfortunately, they had a bit of a reputation for producing a bitter brew. That's what happens when you keep sending boiling water over the same tired coffee grounds.

In 1972, Mr. Coffee fixed our caffeine fix. The automatic drip machine was faster and brewed a better-tasting cup of coffee. Within just a few years, 5 million Mr. Coffee machines had found their way into kitchens. By the late '70s, department stores were selling more than 40,000 of them a day. Just like that, the percolator was pushed aside, destined for garage sales or the back of the cupboard.

Percolators continued to become less and less relevant as more drip machines hit store shelves. Keurig entered homes in 2004, and we now have a dizzying array of home options — even espresso machines that sync with your phone. Despite all these options, not all coffee drinkers have given up on percolators. Supposedly, with the right technique, it's possible to brew a strong, delicious cup. For these caffeine enthusiasts, outdated percolators remain part of the daily grind.

11. Receiving daily fresh milk from the milkman

Bettmann/Getty Images

Milk spoils quickly. So, before every kitchen came equipped with a reliable fridge, getting daily delivery was the safest and most cost-effective way to get milk. Into the 1950s and '60s, the milkman was part of daily life for many families. Each day, he'd swing by the house, collect your empty glass bottles, and leave behind fresh ones filled with cold milk. Some homes had insulated boxes on the porch and others had fancy little double-doored cubbies built right into the wall, so your milk could magically appear without even opening your front door.

But as America expanded into the suburbs, the milkman's job got trickier. His route grew longer, delivery costs went up, and meanwhile, more folks were buying cars and refrigerators. Grocery stores got bigger, with sprawling refrigerated sections ready to stock everything from cheddar to chocolate milk. Plus, new processing methods helped milk last longer. The milkman was no longer needed to get milk at home. By 1975, fewer than 7% of households still had milk delivered. By 2005, that number had trickled down to under 1%. The clink of glass bottles on the porch no longer echoed through the ages.

But the milkman (or milkwoman) is not extinct! Interest in fresh and local food has helped keep the tradition alive. Some local dairies deliver to thousands of customers, many of whom appreciate both the convenience and quality of fresh milk. Nostalgia is tasty and packed with calcium.

12. Spending hours a day cooking

DirkVG/Shutterstock

A 2013 report by Nutrition Journal revealed something your grandma probably already suspected — Americans just aren't cooking like they used to. Compared to 1965, fewer of us are stepping into the kitchen each day — and those who do are spending way less time there. A follow-up study in 2018 showed a small uptick in home cooking, but it was still nowhere near the levels of the past. That 2018 study noted "increased food costs, decreased time availability, and lack of skill" as key factors in the decline of overall cooking.

Americans buy prepackaged food and eat out more than in the past. We've become pros at navigating the frozen food aisle and local takeout menus. The trend was already developing in the 1980s. The book "Recent Social Trends in the United States 1960-1990" explained that, "Between 1950 and 1980, the fraction of family food expenditures spent on meals away from home doubled." So what'll be? Double Whopper, Double-Double, or a Double Decker Taco?

Even when we do cook these days, convenience often enters the kitchen. Taco Tuesday might not be a drive-thru, but the meal can still be sped up with pre-seasoned taco meat, pre-shredded cheese, pre-diced onions, a squirt of sour cream from a tube, and a tub of fresh pico de gallo. And many of us aren't loading up all these delicious ingredients into from-scratch flour tortillas. Who can blame us? Life is busy, and weeknights don't come with extra hours.