Colliding Photons In Crossed Beams Of Light Create Virtual Particles That Test The Standard Model

Colliding Photons In Crossed Beams Of Light Create Virtual Particles That Test The Standard Model

Particles known as tensor mesons are created when high-energy photons interact. These mesons have now been proposed to have a larger effect on photon behavior than previously thought, and provide a new way to test the validity of the Standard Model of particle physics.

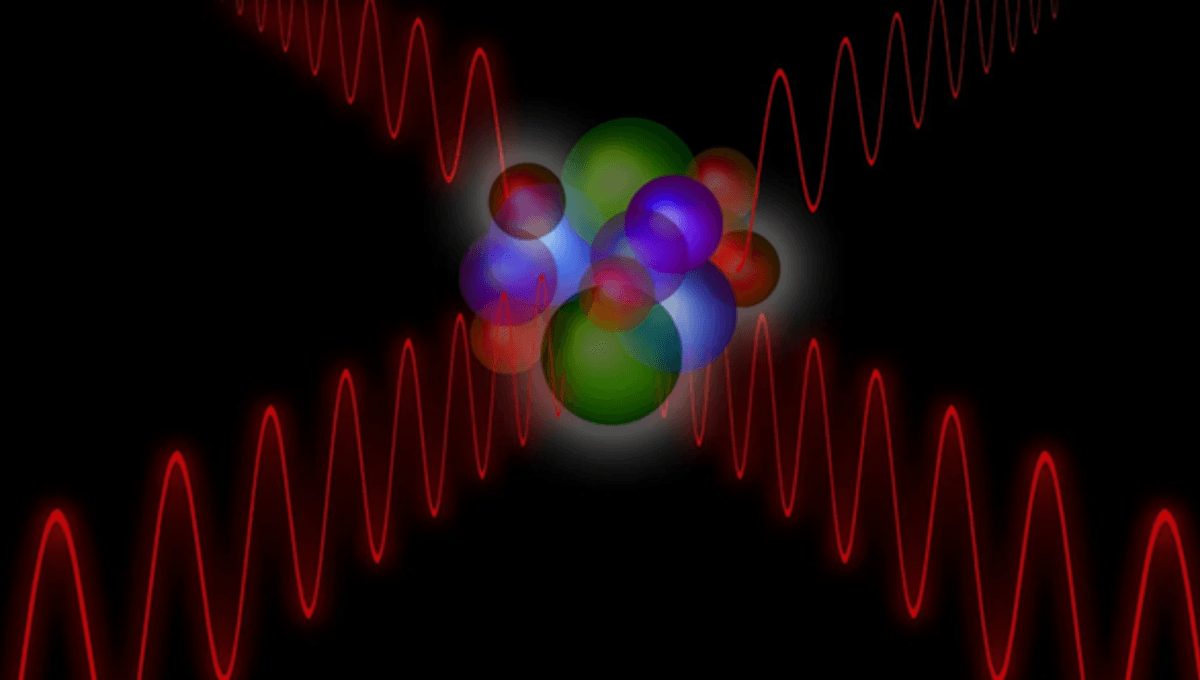

Here’s an experiment any reader can try. Take two torches into a dark room. Have the beams cross and then turn one on and off. Whatever the one beam’s status, the other appears unaffected. In other words, photons appear capable of passing through each other without consequences. Naturally, this experiment isn’t conducted with the precision needed to observe subtle effects, but even when repeated with lasers, the results are normally the same. However, under the right circumstances, exceptions emerge. When particle accelerators make heavy ions almost collide, the interactions can radiate light whose interacting photons sometimes produce virtual particles. Such particles exist only briefly before winking out of existence, but while they do, they can shape reality, including affecting other photons, causing slight changes in direction. New research shows that tensor mesons have a more important role in these redirections than previously recognized. Virtual particles take advantage of the quantum capacity to both exist and not exist at the same time, in superpositions of each. This makes them impossible to measure directly, but that doesn’t mean they are purely hypothetical. "Even though these virtual particles cannot be observed directly, they have a measurable effect on other particles," said Dr Jonas Mager of TU Wien in a statement. "If you want to calculate precisely how real particles behave, you have to take all conceivable virtual particles into account correctly. That's what makes this task so difficult – but also so interesting." An example of this process involves two photons scattering off each other, and producing an electron-positron pair. Before the products annihilate each other, photons can be affected by their presence. When the interacting photons have shorter wavelengths, and therefore the energy is greater, heavier particles can be produced, including mesons, composed of a quark and an antiquark. "There are different types of these mesons," said Mager. "We have now been able to show that one of them, the tensor mesons, has been significantly underestimated.” The influence of the tensor mesons turns out not only to be considerably greater than previously thought for interactions below 1.5 billion electron volts, but in the opposite direction. Mager and co-authors reached these conclusions using holographic quantum chromodynamics (QCD), which involves mapping the usual four dimensions of space and time onto a space in which gravity acts as a fifth dimension. "The tensor mesons can be mapped onto five-dimensional gravitons, for which Einstein's theory of gravity makes clear predictions," said Professor Anton Rebhan. Computer simulations and analytical results reach the same conclusions on tensor mesons' significance, the authors claim. Moreover, holographic QCD has been found to accurately represent aspects of light-light scattering that other methods do not. Nevertheless, the work has yet to be confirmed experimentally, although Rebhan expressed the hope that the study will encourage heavy ion trials that will do that. The incentive to make this work a priority, given the scarce capacity of large particle accelerators, is that in the process, it could probe tension between the Standard Model of particle physics and some experimental data. “Through the effect of light-light scattering, [tensor mesons] influence the magnetic properties of muons, which can be used to test the Standard Model of particle physics with extreme accuracy,” Mager said. The study is published in Physical Review Letters.