People have been searching for the mysterious “sixth sense” ever since… well, since 1761 at least, but potentially since the days of Aristotle. It was he, after all, who originally declared the number of senses to be five, and labeled them too: touch, taste, smell, sight, and hearing.

But Aristotle said a lot of garbage. The truth is that calling any one sense “the sixth sense” makes about as much, uh, sense as labeling, say, barium as “the fifth element” after earth, air, fire, and water (when, as we all know, it’s actually Mila Jovovich). Humans have between three and 33 senses, depending on how you count them – and as a new study describing a previously-unknown “neurobiotic sense” that connects the gut to the brain shows, that number is only going up. Still, there’s evidently something attractive about the idea of a “sixth” sense – otherwise, why would so many have been announced over the years? Such as… Ah, the OG “sixth sense”. So famous that there’s even a movie about it, the ability to perceive things beyond the physical realm has long been posited – and repeatedly debunked. One step down from that – and 100 percent more real – is our “sense” of intuition. This sometimes feels like it could be supernatural, but the truth is likely more prosaic: “It’s the learned, positive use of unconscious information for better decisions or actions,” University of New South Wales neuroscientist and psychologist Joel Pearson told The Guardian in 2024. There’s a good reason why these two don’t qualify as sixth senses, however. The first – well, that’s obvious: it doesn’t exist, or at least hasn’t been proven to yet. The second, on the other hand, simply isn’t a “sense” at all – it’s more like an unconscious calculation based off input from our senses. Enter “sixth sense” into a search engine, and – once you get past the movie reviews – you’ll probably see these ones suggested before anything else. Proprioception and kinesthesia are often used semi-interchangeably, but they’re actually quite different – albeit highly intertwined. The easiest way to describe each of them, as well as how they interact with each other, is probably with an example. So: close your eyes and put your hand on your head. Easy, right? But when you think about it, a lot had to go into that to make it happen: you had to know where your head was in space; you had to know where your hand was in relation to your head; you had to know exactly how and in what direction to move your arm in order to get it to its cranial destination – and you had to do it all without being able to see it. That you could do all that is thanks to the twin senses of proprioception and kinesthesia – proprioception to inform where your hand and head were in space, and kinesthesia to tell you how to move one on top of the other. Now we come to the weirder ones. You’re probably more used to thinking of echolocation as a cetacean or bat sense – but with enough gumption, you can learn it yourself in a matter of weeks. “The adult human brain is very adaptable when it comes to sensory processing,” explains a 2024 study in which researchers taught 26 people, both blind and sighted, to use echolocation. And indeed, not only did the cohort pick up the “new” sense, but the researchers saw notable changes in brain makeup and activation as a result: “We found that blind participants and sighted participants together showed a training-induced increase in activation in left and right V1 [Primary Visual Cortex] in response to echoes,” the paper notes, as well as “a training induced increase in activation in right A1 [Primary Auditory Cortex] in response to sounds per se” and “an increase in gray matter density in right A1.” Perhaps less convincing is the argument for magnetoreception in humans – though there is some intriguing evidence for it. A smattering of studies have shown that our brains do show some kind of reaction to magnetic fields, and the theory has a handful of strong devotees. But is this really a “sixth sense”? Well, as Thorsten Ritz, a biophysicist at University of California, Irvine, rather evocatively put it for Science Magazine, “if I were to […] stick my head in a microwave and switch it on, I would see effects on my brain waves. That doesn't mean we have a microwave sense.” So what’s the latest in “sixth sense” news? Well, as of last week, the buzzword is “neurobiotic” – a “sense by which the host adjusts its behavior by monitoring a gut microbial pattern,” according to a new paper describing the sense. Now, if you’re used to thinking of a “sense” as a way to interpret the outside world, then this new neurobiotic sense may seem a little strange. It works by detecting an ancient protein called flagellin – usually found in the tail-like structures of certain bacteria in our guts, but set free when we eat. Those free-roaming flagellin proteins are then detected by neuropods – special sensor cells in the gut that link it up with the nervous system – which fire off a message to the brain. That message: “okay, you can stop eating now.” The discovery comes after a series of experiments in mice. “We were curious whether the body could sense microbial patterns in real time,” Diego Bohórquez, an associate professor of medicine and neurobiology and senior author of the study, explained in a statement. “[N]ot just as an immune or inflammatory response, but as a neural response that guides behavior in real time.” So, for one set of mice, the team let them fast overnight and then gave them a dose of flagellin into their colon. The result: they ate less than a similar mouse cohort who hadn’t had the bacterial injection. Conversely, when this experiment was repeated in mice who lacked the TLR5 receptor – the cells which help the neuropods detect the flagellin – no such effect was seen. Essentially, this sense – even though we’re not aware of it in the same way as we are the big five – not only informs how full we feel, but it also changes how we act because of it. “Looking ahead, I think this work will be especially helpful for the broader scientific community to explain how our behavior is influenced by microbes,” Bohórquez said. It may not be a “sense” by Aristotle’s definition – and it’s definitely not the sixth one – but it’s certainly an intriguing discovery, with implications far wider-reaching than just better understanding how and why we feel full when we do. “One clear next step is to investigate how specific diets change the microbial landscape in the gut,” Bohórquez said. “That could be a key piece of the puzzle in conditions like obesity or psychiatric disorders.” The study is published in Nature. Extrasensory perception or intuition

Kinesthesia and proprioception

Echolocation and magnetoreception

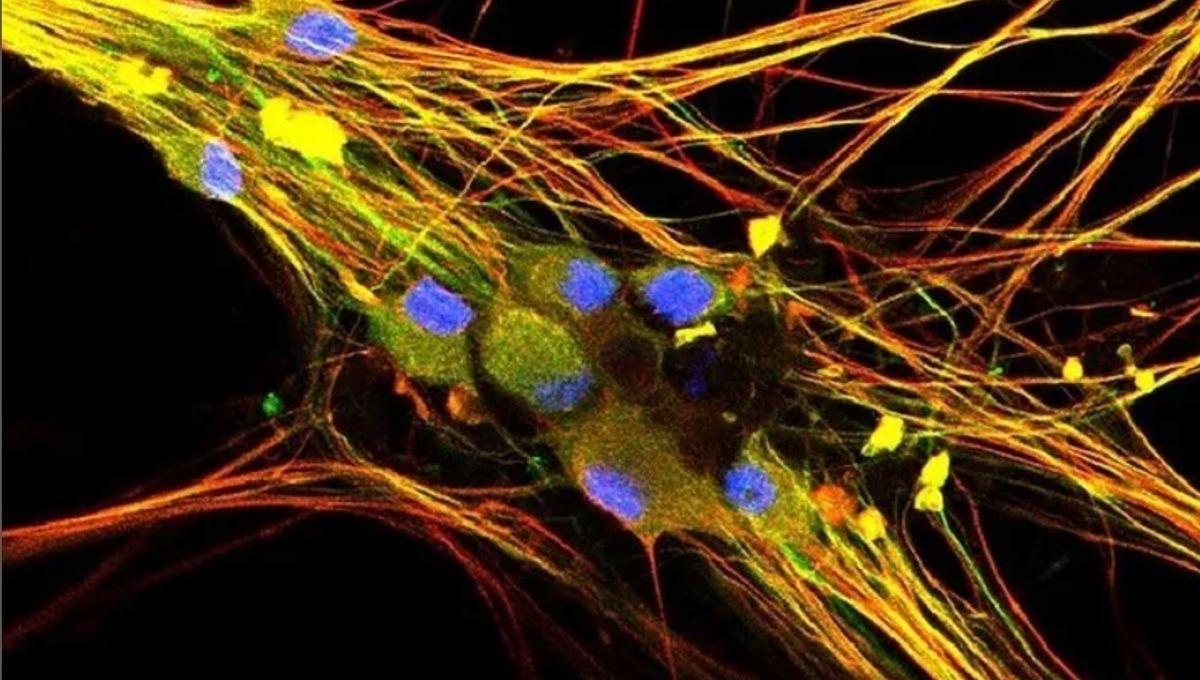

New “neurobiotic sense”