How do you stop an invasive species from taking over an ecosystem and decimating the local species that live there? Well, if it’s Florida, you use a vibrating robot bunny.

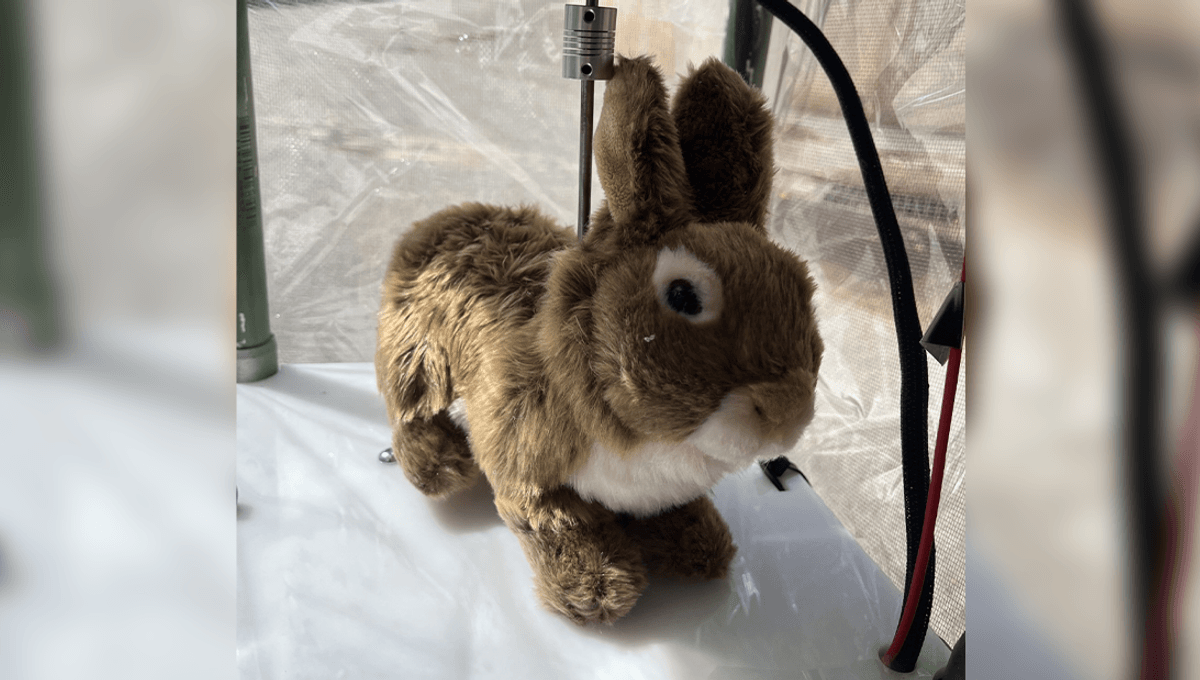

“These things […] may sound a little crazy,” admitted Robert McCleery, a professor at the University of Florida’s Wildlife Ecology and Conservation Department. But, he told The Palm Beach Post, “working in the Everglades for 10 years, you get tired of documenting the problem. You want to address it.” Burmese pythons are, as their name suggests, Burmese in origin. They come from Southeast Asia. But in the 1970s, they began hanging out Stateside – in Florida’s Everglades, to be exact – and in the 21st century, they became an established breeding population in the area. That’s… bad. Even if you’re a fan of these great big slithery fellas, the effect they’ve had – and continue to have – on the local ecosystem is nothing short of devastating. Between 2003 and 2011, for example, the number of raccoons seen in areas inhabited by Burmese pythons dropped by more than 99 percent; a similar decrease was seen (or not seen, we should perhaps say) in the numbers of opossums, and bobcat numbers dropped by 87.5 percent. Rabbits – the non-robotic kind – disappeared completely. “Twenty years ago, the [Everglades] would have been teeming with wildlife,” Mike Kirkland, senior invasive animal biologist at South Florida's water management district, told BBC Future in 2024. “Now I challenge you to find a single deer, possum, or squirrel. They have decimated our native wildlife.” In response, a whole heap of measures have been taken to try to curb the reptilian invasion. Since 2021, the Burmese python has been illegal to buy, sell, or transport in Florida, and those already resident as pets must be chipped and registered. Professional snake hunters have been brought in to advise locals; the snakes are tracked with near-infrared cameras and even DNA technology. Burmese pythons have also been hybridizing with Indian pythons in the Everglades, complicating matters. Image credit: Heiko Kiera/Shutterstock.com But many projects have been trialed that had a distinctly more… Floridian flavor. We’re talking about the annual Florida Python Challenge: a 10-day-long hunt with a five-figure cash prize for whoever bags the longest snake, or the so-called “scout snakes”. Male pythons that are caught, tagged with a radio-telemetry tracker, and sent back out to lead conservationists to females during the breeding season. But… they kind of work, is the crazy thing. “There’s very good evidence that the scout snake program is our most effective and least biased method,” Andrew Durso, a herpetologist at Florida Gulf Coast University, told The Guardian last month. “It doesn’t just limit us to targeting human accessible areas and it’s super targeted toward those reproductive females.” “If you can take out one female, it’s not just that single python,” he explained. “[It’s] all of her current and future reproduction, that’s thousands of eggs that will never be laid.” And really, if cyborg snakes are where we’re putting the standard – then who’s to say robo-bunnies are “too far”? Imagine you’re a Floridian python, slithering around the Everglades on the lookout for a stray raccoon or alligator to chow down on. You’ve heard tales from generations past that once, rabbits roamed these lands – a tasty morsel that you can now only dream of. And then you spot it. A shaking, spinning, warm, and fuzzy bunny, sitting there in front of you, completely inconspicuously inside what your python brain definitely does not register as a suspicious trap-like object. How can you resist? Nothing to see here... just a regular bunny... Image courtesy of Robert McCleery There’s just one problem: the bunny is a lie. It’s nothing but a toy for juvenile humans, with its stuffing removed and replaced with mechanical components that can mimic the real thing. And now you’re dead. “It’s projects like [this] that can be used in areas of important ecological significance where we can entice the pythons to come out of their hiding places and come to us,” Kirkland said in a July 7 presentation to the Big Cypress Basin Board seen by the Palm Beach Post. “It could be a bit of a game changer.” It’s certainly an improvement for Florida’s bio-bunny population. Initially, the project – which (now) uses the robo-bunnies as bait to attract pythons so conservationists can trap and kill them – used real rabbits as the lures. They “didn’t fare well,” McCleery said. But they were successful, attracting pythons at a rate of about one a week. What McCleery and his colleagues needed, then, was something that looked, to a python, like a rabbit – but had none of the pesky mortality-based drawbacks of the real thing. The solution: 40 robot bunnies, built out of stuffed toys and refitted with machinery to make them move, heaters to make them blood-warm, and, if all goes well in phase two of the project, even bunny-perfume to give them the right scent. Well doesn't that just look toasty enough to eat (if you're a Burmese python)? Image courtesy of Robert McCleery “We want to capture all of the processes that an actual rabbit would give off,” McCleery told the Palm Beach Post. “But I’m an ecologist. I’m not someone who sits around making robots.” It’s a novel idea, for sure – but as to whether it’s successful or not, we’ve yet to find out. The data from the study won’t be available until November, McCleery told IFLScience, and as such he’s holding out on commenting further until then. Neither can you ask him where the bunnies are hanging out in the state. “I don’t want people hunting down my robo-bunnies,” he told The Palm Beach Post. But if they work out, these robo-bunnies may prove another valuable weapon in the anti-python arsenal. While ridding the area of the species entirely is probably a lost cause at this point, a strong enough management system may at least mitigate some of their effects on the local ecosystem – maybe even allowing for the return of the robo-bunnies’ biological forebears. “As with most environmental issues, a multi-pronged strategy of different efforts working in concert with one another is really the best path forward,” Kirkland told The Guardian. “In the future I see the python population being greatly reduced, and to a point where we can begin to see a robust return of our native animal populations, which is why we’re doing all this to begin with.” “I’m confident we’re going to be able to manage this species,” he said, “to the point where we’re seeing our deer populations, our foxes, our possums, our raccoons and so on, restored to the Everglades.”A slithery problem

A fluffy foe

The proof in the pudding