Humans are pretty good at making things hot. Heck, it’s pretty much our species’ entire claim to fame at this point. But just how hot can we go when we really put our minds to it?

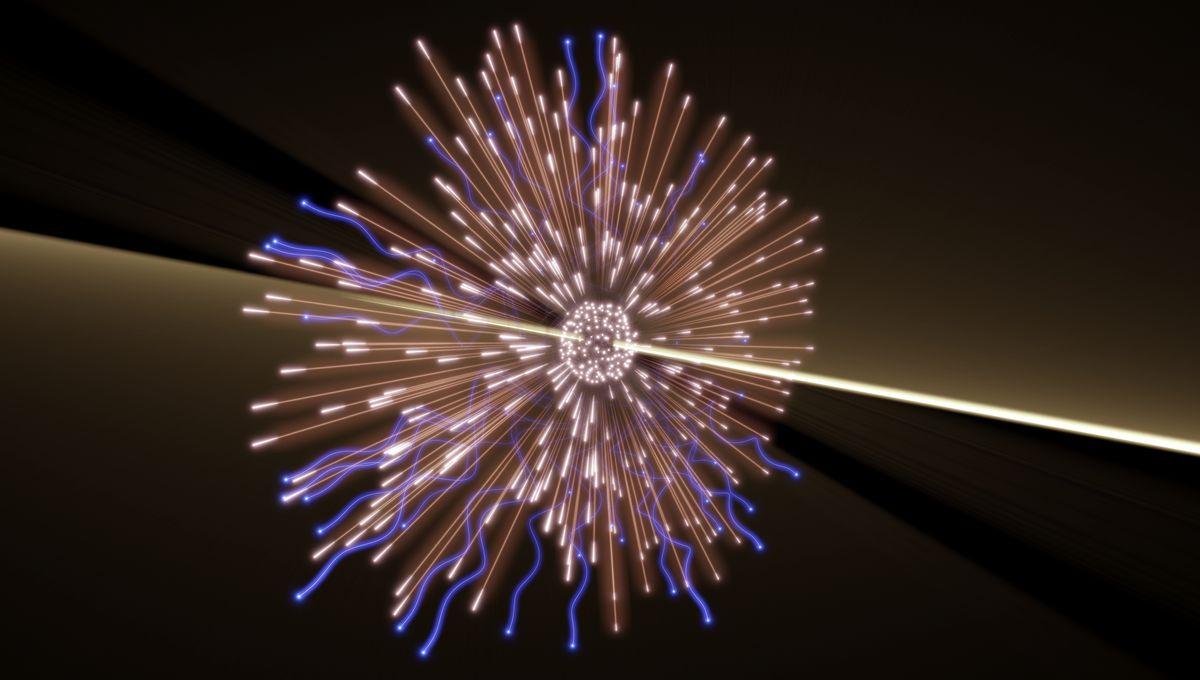

It might seem like a frivolous question – but our ability to heat things up has been responsible for some of the biggest leaps and bounds in human history. Take the Bronze or Iron Ages, for example: both periods characterized by the use of a particular metal, and therefore both impossible without being able to create and maintain temperatures of a few thousand degrees. The hottest ever temperature created – artificially, at least; so far, we’ve not been able to beat the 10 trillion or so Kelvins at the center of a quasar – is similarly a testament to human ingenuity. So, what was it? Remember 2012? The year that started with “CERN might have broken the laws of physics”, peaked in the middle with “we’ve discovered the God particle”, and ended with “pretty sure there’s meant to be some kind of apocalypse going on now”. Amongst all that, it’s not surprising that certain other achievements have slipped our memories – like how, in August of that year, CERN casually smashed through the previously held record for highest artificial temperature created. And we’re not talking “ooh, ow” kind of temperatures here – we’re not even talking “as hot as the Sun itself”. That would be a measly 15 million degrees Celsius (27 million degrees Fahrenheit), even at its hottest. What CERN got was much hotter than that. “Today there's nothing even remotely as hot as the matter we create[d] in ALICE,” said Kai Schweda, Deputy Spokesperson of the ALICE Collaboration, in PBS’s Be Smart. (ALICE, by the way, stands for A Large Ion Collider Experiment, so named “because it's a large ion collider experiment.”) “If you go to our sun, you have 15-million-[degree] temperatures,” Schweda explained. “The hottest stars [are] 100 million. So what we create is 100,000 times hotter than anything else in today's universe.” That’s right: the temperatures created in CERN’s Large Hadron Collider, or LHC, were an astonishing 5 trillion Kelvin – roughly 5 trillion degrees Celsius, because who’s counting the odd 273 when you’re dealing in trillions, or 9 trillion degrees Fahrenheit. It’s thought to be the temperature of the universe microseconds after the Big Bang, when all matter existed as a kind of primordial quark-gluon plasma soup. “This is only one leading example of the scientific opportunities in reach of the ALICE experiment,” Paolo Giubellino, spokesperson of the ALICE collaboration, said at the time. “We are closer than ever to unravelling the properties of the primordial state of the universe.” So how does one go about creating things that hot? Well, it’s simple really: all you need is a 27-kilometer (17-mile) long circular track under Switzerland consisting of incredibly strong super-cooled superconducting electromagnets that are capable of accelerating particles around at relativistic speeds; a couple of lead ions; and a really, really good thermometer. “The LHC is a ring over 16 miles long, and particles can travel around it over 11,000 times every second,” PBS explains. “They reach 99.9999991 percent of the speed of light. And when they slam together, they create absolutely enormous amounts of energy.” Exactly how much energy is created depends on how big those particles are – remember: E = mc2 means that energy scales with mass. That’s one reason why the scientists involved chose lead ions for the experiment – they are (for ions) very large, each containing hundreds of protons and neutrons. Smash them together at these incredible speeds, then, and these tiny particles in the nuclei will release a bunch of their energy in a very small amount of space and time – with the result, in CERN’s own words, being “a fireball of quarks and gluons”. It’s so hot that our gag about needing a good thermometer doesn’t really work – the only way to measure those kinds of temperatures is via complex math and physics based off high-precision analysis of the after-effects of these smashing experiments. “Heavy-ion physicists have learnt how to make use of ‘overtones’ in their study of the quark–gluon plasma,” said CERN theorist and quark–gluon plasma specialist Urs Wiedemann back in 2020. “Such overtones can be measured by analyzing the collective flow of particles that fly out of the plasma and reach the detectors,” he explained, and that data is then “used by theorists to characterize the plasma’s properties, such as its temperature, energy density and frictional resistance, which is smaller than that of any other known fluid.” You can kind of think of it as the LHC “hearing” the properties of the quark-gluon plasma. “If we listen to two different musical instruments with closed eyes, we can distinguish between the instruments even when they are playing the same note,” Wiedemann pointed out. “The reason is that a note comes with a set of overtones that give the instrument a unique distinct sound.” Similarly, “the initial stage of a heavy-ion collision produces ripples in the plasma that travel through the medium and excite overtones,” he explained – a unique signature that, with the right scientific nous, can be used to figure out exactly what happened in that split-second collision. Working all that out – as well as making sure it’s all correct and you haven’t accidentally carried a one or broken the laws of physics – is no easy feat. Neither is it quick. Here’s the thing: the first time the LHC managed to create these trillion-degree temperatures wasn’t actually 2012. It was 2010. It just took two years to actually measure and confirm the result – that’s why the official Guinness World Record is dated August 13, 2012. Okay, you may think – so physics takes time. So what? Well, quite – but spare a thought for the team at Brookhaven National Laboratory in New York, who in June 2012 – literally two months before the CERN result – made headlines for using their Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) to produce the highest-ever recorded artificial temperature: 4 trillion Kelvin. The team was even certified by Guinness. It’s just a shame it was so short-lived. Still, the New York team was sanguine – and for good reason. “Although the LHC collisions release 25 times more energy than the RHIC collisions, we don’t see much difference in the droplet-formation process,” Julia Velkovska, Professor of Physics at Vanderbilt University and a member of the LHC’s CMS detector team, said in 2015. “Once you have reached the threshold, adding more energy doesn’t seem to have much effect,” She explained. “I guess you can’t get more perfect than perfect!”The hottest thing ever created: 5 trillion Kelvin

How did they do it?

Get it while it’s hot