The Weird Mystery Of The "Einstein Desert" In The Hunt For Rogue Planets

The Weird Mystery Of The "Einstein Desert" In The Hunt For Rogue Planets

The first confirmed discovery of an exoplanet was announced in 1992, when astronomers Aleksander Wolszczan and Dale Frail reported two or more planet-sized bodies orbiting pulsar PSR1257 + 12 using the Aricebo telescope. The first confirmed discovery of a planet orbiting a main-sequence, Sun-like star came a few years later in 1995, in the form of a "hot Jupiter" planet.

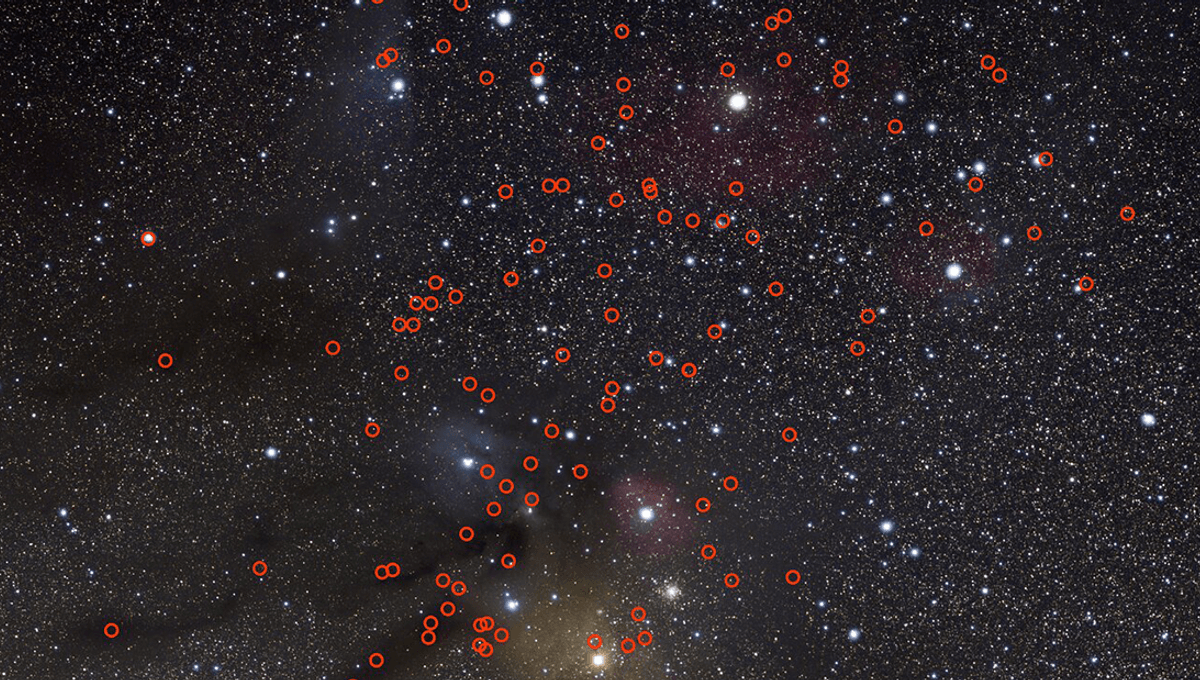

The rest of this article is behind a paywall. Please sign in or subscribe to access the full content. Up until the mid-1990s, detections were tantalizing as they were rare. But since then, there has been an explosion in exoplanet detections, thanks to dedicated space-based observatories like Kepler and TESS, as well as improved Earth-based methods and telescopes. We have now discovered over 6,000 exoplanets, with many more potential detections waiting to be confirmed. As well as planets orbiting stars, there have been more recent detections of a rarer type of object, known as "rogue planets", "free-floating planets" (FFPs), or sometimes isolated planetary-mass objects (iPMOs). As the many names imply, these are planetary-mass objects that are free-floating through the galaxy, drifting alone without a host star to call home. The detection of these objects is a little trickier than finding exoplanets, which is in itself already pretty tricky. In order to detect bog-standard exoplanets orbiting a star, astronomers can use a number of methods. These include looking for "transits", or spotting the dipping of light as a planet passes in front of its host star, and looking for telltale "wobbles" in a star's motion caused by the gravitational tug of a planet orbiting its host. The vast majority of exoplanet detections have been made using these methods, but there are a few others, such as directly imaging light from the planets themselves, a technique that has found over 60 exoplanets so far, and microlensing. While great at finding exoplanets, it is near impossible to find rogue planets in the same way. In short, if there's no star to have an effect on, there's nothing for the planet to transit or wobble. For detecting rogue planets, astronomers rely on microlensing, when these planets pass in front of a far more distant star and, for a short time only, magnify its light. "Gravitational lensing is an observational effect that occurs because the presence of mass warps the fabric of space-time, sort of like the dent a bowling ball makes when set on a trampoline," NASA explains. "The effect is extreme around very massive objects, like black holes and entire galaxies. But even stars and planets cause a detectable degree of warping, called microlensing." The first detection of a rogue planet was made a little later than the first exoplanets, taking place in 2000. Despite their rarer discovery, surveys have suggested that these objects far outnumber stars and the planets that orbit them, with potentially trillions floating through the Milky Way. One interesting mystery about these planets is known as the "Einstein desert", named after Albert Einstein, whose theory of general relativity predicted gravitational lensing. In short, we have detected many microlensing events which are thought to be caused by low mass objects, and many microlensing events which are thought to be of high-mass objects, but very few events in between. There is a "desert" between these two mass ranges, where few objects have been observed. "A systematic search for FSPL [finite-source point-lens] events identified a gap in the 𝜃E distribution at 9 ≲ 𝜃E ≲ 25 micro-arc sec [µas], which was referred to as the Einstein desert," a new paper on the topic of a Saturn-mass rogue planet explains. "All nine known FSPL FFP events have 𝜃E below this desert, which implies that the lensing objects are less than one Jupiter mass (MJ). These events have been interpreted as free-floating planets that were ejected from protoplanetary disks. By contrast, all other detected FSPL events are above the desert, which implies that they were produced by BDs [brown dwarfs] and stars." This is puzzling, as we don't really know why this gap should exist. If planets are regularly expelled from their solar systems, we should expect to see plenty of gravitational lensing events in the Saturn-Jupiter mass range. And yet these don't show up all that often, though recently a planet around Saturn's mass was observed by several telescopes. There remains a big gap between the low-mass planets, believed to have formed as planets do in protoplanetary disks, before becoming ejected from their host systems, and objects like brown dwarfs, which are thought to form as stars do, though their masses are too low to begin stellar fusion. As yet, we do not have a perfect explanation for the Einstein desert, though the new paper adds evidence to the hypothesis that the cause might just be that larger planets are less easily ejected from their systems. "Although previous FFP events did not have directly measured masses, statistical estimates indicate that they are predominantly sub-Neptune mass objects, either gravitationally unbound or on very wide orbits," the team writes in their paper. "Such objects can be produced by strong gravitational interactions within their birth planetary systems. We conclude that violent dynamical processes shape the demographics of planetary-mass objects, both those that remain bound to their host stars and those that are expelled to become free floating." The Vera C. Rubin Observatory and the Nancy Roman Space Telescope will provide much more data to work on, and many more rogue planets to study, and clear up the Einstein desert.