A 1-Kilometer-Long Stone Age Megastructure Under The Baltic Sea Is Being Investigated By Archaeologists

Is A 1-Kilometer-Long Stone Age Megastructure Hiding Under The Baltic Sea?

Megastructures from the European Stone Age are incredibly rare. Long before agriculture, cities, or authoritative kings, moving massive stones and organizing large labor forces was nearly impossible. Despite anything, this was a time before metal tools, wheels, or written language. Yet along the Baltic Sea coast in Northern Europe, an archaeological discovery suggests that prehistoric humans were heavily inventive in pushing the limits of what was possible.

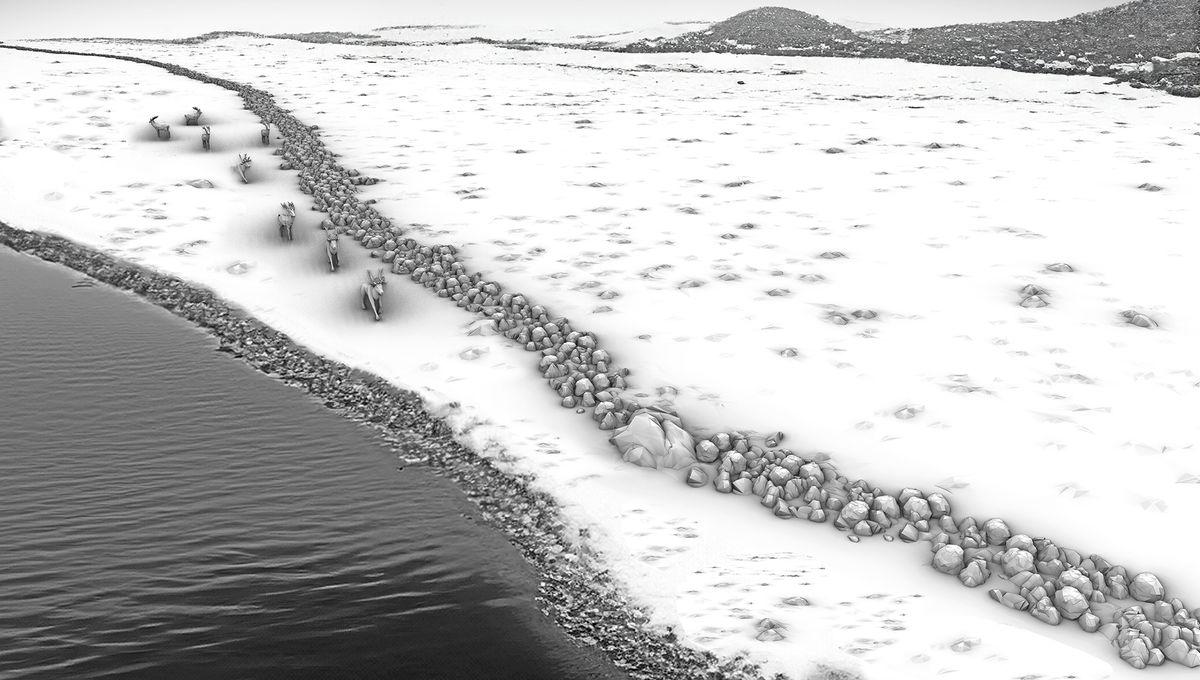

Just off the shores of the Bay of Mecklenburg in Germany, researchers uncovered the submerged ruins of a wall that runs almost 1 kilometer (0.6 miles) in length, crafted out of 1,673 individual stones that measure less than 1 meter (3.2 feet) in height. It’s estimated that the structure, known as the Blinkerwall, was built around 11,000 years ago, before the brackish waters of the Baltic Sea submerged this area. Archaeologists believe the most plausible explanation is that it was constructed by hunter-gatherers as a tool for trapping reindeer and other ungulates as they migrated through the region. “At this time, the entire population across northern Europe was likely below 5,000 people. One of their main food sources were herds of reindeer, which migrated seasonally through the sparsely vegetated post-glacial landscape,” Marcel Bradtmöller, archaeologist from the University of Rostock in Germany, said in a statement last year after discovering the site. "The wall was probably used to guide the reindeer into a bottleneck between the adjacent lakeshore and the wall, or even into the lake, where the Stone Age hunters could kill them more easily with their weapons," he added. That’s the theory, at least. An interdisciplinary joint research project called SEASCAPE, led by the Leibniz Institute for Baltic Sea Research Warnemünde (IOW), has recently announced that they’re planning on investigating the submerged structure with further archaeological work. Their aim is to finally confirm how, when, and why the structure was built by humans. “With SEASCAPE, we are breaking new scientific ground, not only in the truest sense of the word below the sea surface, but also through the close collaboration of very different disciplines – geophysics, archaeology and palaeo-environmental research – which are all essential for a meaningful interpretation of the structures,” Jacob Geersen, a marine geologist at the IOW and leader of the project, said in a new statement. Similar archaeological structures to the Blinkerwall have been found elsewhere in the world, most of which have been defined as hunting structures. The desert landscapes of Western Asia, as well as parts of North Africa, are filled with structures called desert kites that were used to herd and capture wild gazelles and ibex. There’s even a 9,000-year-old example of a trapping structure at the bottom of Lake Huron, one of the five Great Lakes of North America. Discoveries like these challenge the idea that prehistoric humans were disorganized knuckle-draggers. With few tools and a minuscule population, they were able to build complex structures that required a huge amount of thought and planning. Never underestimate the human mind, even in the Stone Age.