Titan, Saturn’s Biggest Moon, Might Not Have A Secret Ocean After All

Titan, Saturn’s Biggest Moon, Might Not Have A Secret Ocean After All

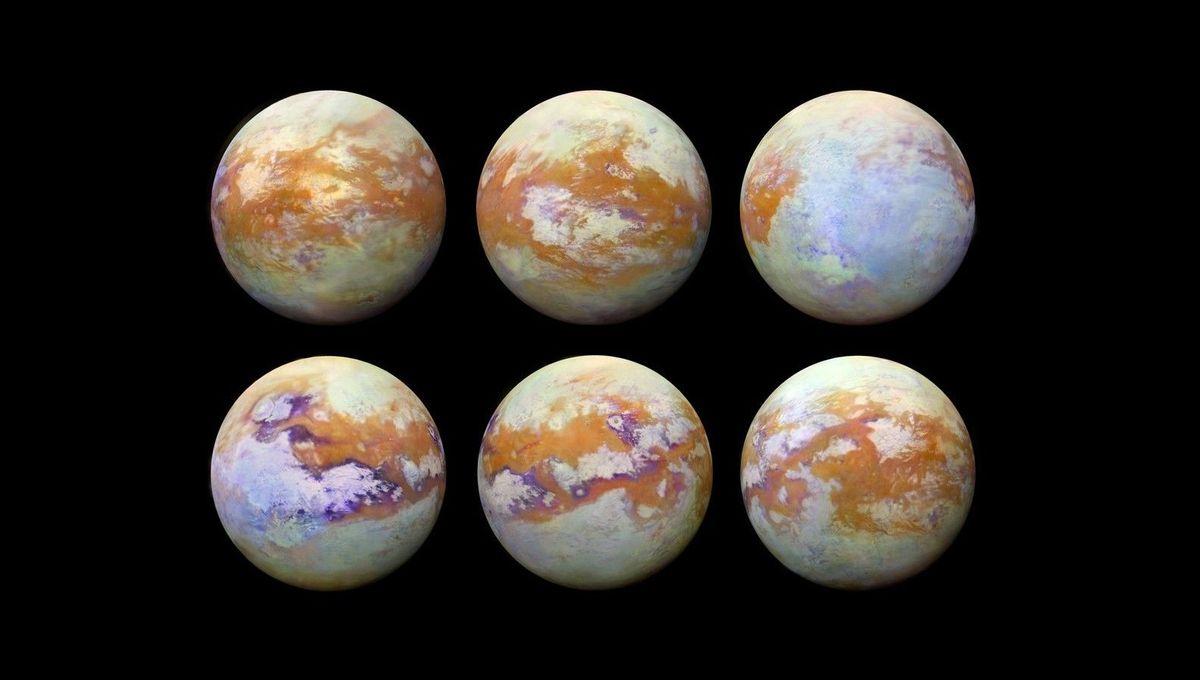

Titan is the only other world in the Solar System with lakes and rain. Unlike Earth, those are not made of water, but methane and other hydrocarbons, because it is too cold for liquid water. There is plenty of water ice on Titan though, and observations in the 2000s suggested that the moon might be hiding a secret water ocean deep under its surface. However, a new study has found this might not be the case after all.

The rest of this article is behind a paywall. Please sign in or subscribe to access the full content. Missions such as Galileo around Jupiter and Cassini around Saturn have discovered over the last three decades that the giant planets have icy moons with likely deep oceans buried beneath their surfaces. It might seem weird thinking about a deep ocean beneath the solid crust when, on Earth, the oceans are on the outside. But the original evidence was compelling. Titan cannot be a fully solid object; it gets slightly deformed under the gravitational pull of Saturn. What was missing in the previous analysis was a detailed modeling of the moon that takes into account the timing of the changes. The new work argues that what they see cannot be explained by a deep ocean as we expect on Europa or Enceladus. It is more like a slushy situation, happening in the underground. No secret ocean for Titan! “Instead of an open ocean like we have here on Earth, we’re probably looking at something more like Arctic sea ice or aquifers, which has implications for what type of life we might find, but also the availability of nutrients, energy and so on,” study author Baptiste Journaux, a University of Washington assistant professor of Earth and space sciences, said in a statement. Titan is in an elliptical orbit around Saturn, so its shape will change more or less depending on its position around the orbit. The team also found that there is a 15-hour delay between the peak of the gravitational pull and the peak of deformation, and that the energy dissipation inside Titan is much greater than what you’d expect if it had a global ocean. A different view was needed. “The degree of deformation depends on Titan’s interior structure. A deep ocean would permit the crust to flex more under Saturn’s gravitational pull, but if Titan were entirely frozen, it wouldn’t deform as much,” Journaux said. “The deformation we detected during the initial analysis of the Cassini mission data could have been compatible with a global ocean, but now we know that isn’t the full story.” Titan is considered a potential location for life outside of Earth. It has a lot of useful and interesting chemistry on its surface, and flowing liquid could make it possible for something to form there. In fact, the slushy ocean actually improves the chances of life on the moon. The model suggests the presence of pockets of water that could reach 20 °C (68 °F). “The discovery of a slushy layer on Titan also has exciting implications for the search for life beyond our solar system,” Jones said. “It expands the range of environments we might consider habitable.” NASA is sending a new mission to Titan, called Dragonfly, which will land and fly around the moon in 2034 to understand if this world can be or is habitable. The study is published in the journal Nature.