Hundreds Of New Giant Viruses Discovered Throughout The World's Oceans

Hundreds Of New Giant Viruses Discovered Throughout The World's Oceans

If there’s one thing worse than a virus, you’ve got to imagine it’s a massive version of the same thing. So it may not sound like good news that scientists from the University of Miami have just discovered some 230 previously unknown types of giant virus, present in just about every ocean across the planet – but we promise, it is.

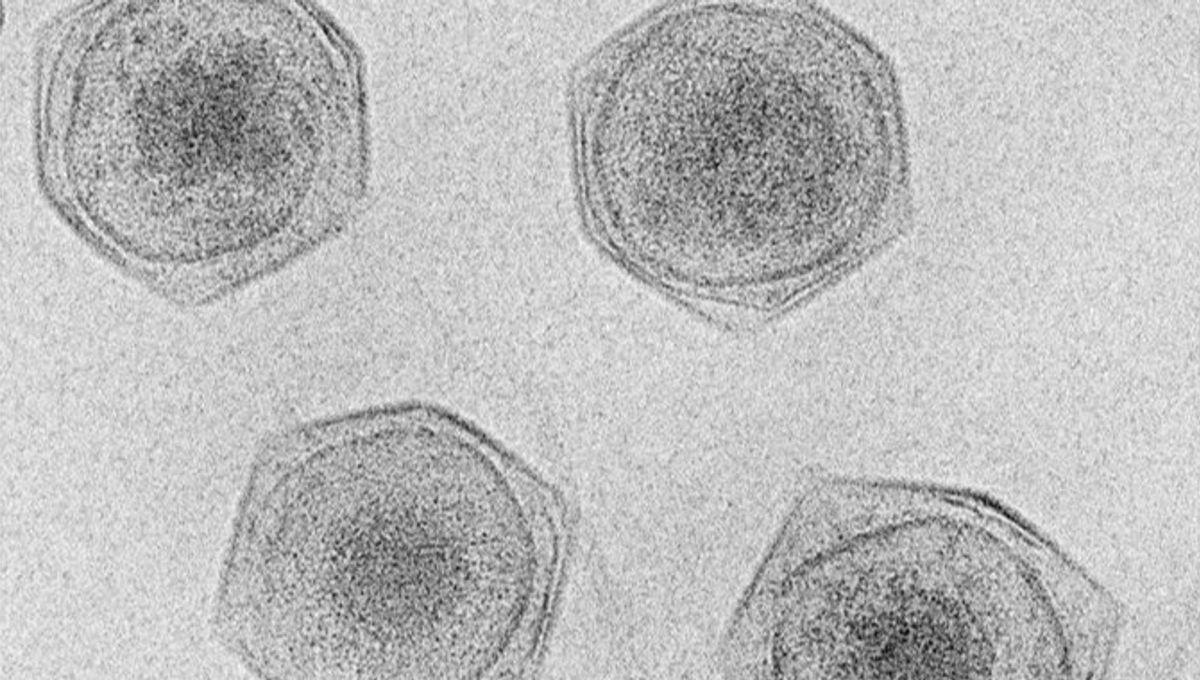

“By better understanding the diversity and role of giant viruses in the ocean and how they interact with algae and other ocean microbes, we can predict and possibly manage harmful algal blooms, which are human health hazards in Florida as well as all over the world,” pointed out Mohammad Moniruzzaman, one of the two authors of the new study and an assistant professor in the University’s Department of Marine Biology and Ecology, in a statement Thursday. “The novel functions found in giant viruses could have biotechnological potential, as some of these functions might represent novel enzymes,” he added. Now, we know what you’re wondering: just how “giant” are we talkin’ here? And the answer is, well, not all that giant, to be honest: the term refers to viruses whose particles can measure as much as two microns, which is about one-fourth the size of a single red blood cell. It’s not huge. But for a virus, it’s a veritable behemoth. Most regular viruses have particles that top out at about 0.4 microns, and some are as small as 0.02. They also contain far more genetic information than your average virus: their genomes can have as many as 2.5 million base pairs, as opposed to most viruses’ tens of thousands. In fact, so weirdly huge are giant viruses, in so many ways, that we didn’t even know they existed until the 1980s – they were, paradoxically, too big for scientists to notice them. “The classic tool for isolating virus particles is filtration through filters with pores of 200 nanometers,” explained James Van Etten, the William Allington Distinguished Professor of Plant Pathology at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, in a 2011 article for American Scientist. “With viruses all but defined as replicating particles that occur in the filtrate of this treatment, giant viruses were undetected over generations of virology research.” On top of that, giant viruses don’t tend to infect humans, or even animals at all – they usually concentrate on protists, like algae or amoebas. Call it self-centeredness, but that tends to put an organism on the back burner, as far as funding and research goes. But with a little spark of spotlight now on them, their importance to the global ecological web is becoming clear. “We discovered that giant viruses possess genes involved in cellular functions such as carbon metabolism and photosynthesis – traditionally found only in cellular organisms,” said Benjamin Minch, lead author of the study and a doctoral student in the Department of Marine Biology and Ecology at the University’s Rosenstiel School of Marine, Atmospheric and Earth Science. “This suggests that giant viruses play an outsized role in manipulating their host’s metabolism during infection and influencing marine biogeochemistry.” It's a discovery that could have great importance for public health – and indeed the health of local ecologies in general. The phytoplankton that these viruses prey on are often the base level of entire ocean ecosystems, so being able to understand them better can help us support the planet’s ever-more precarious marine environments. “Overall, our work provides new insights into the diversity and functional potential of [giant viruses] in the world’s oceans through our addition of 230 genomes with an expanded set of photosynthesis proteins as well as many other metabolic genes,” the paper concludes. “We hope that these new genomes along with protein annotations, will be useful in the expansion of insights into [giant viruses] from further metagenomic datasets across all aquatic ecosystems.” The paper is published in the journal npj viruses.