-

Feed de notícias

- EXPLORAR

-

Páginas

-

Blogs

-

Fóruns

18,000-Year-Old Stalagmite Sheds Light On Why Civilization Started In The Fertile Crescent

18,000-Year-Old Stalagmite Sheds Light On Why Civilization Started In The Fertile Crescent

A stalagmite from a cave in Kurdistan has provided unprecedented detail on local climatic conditions from 18,000 to 7,500 years ago, as Earth was leaving the last glacial period. Lying so close to the valleys where agriculture and civilization were born, the find offers great insight into the conditions that drove their rise. Moreover, the shifts the stalagmite reveals match those occurring in Greenland, showing the global influence on the place where it all began.

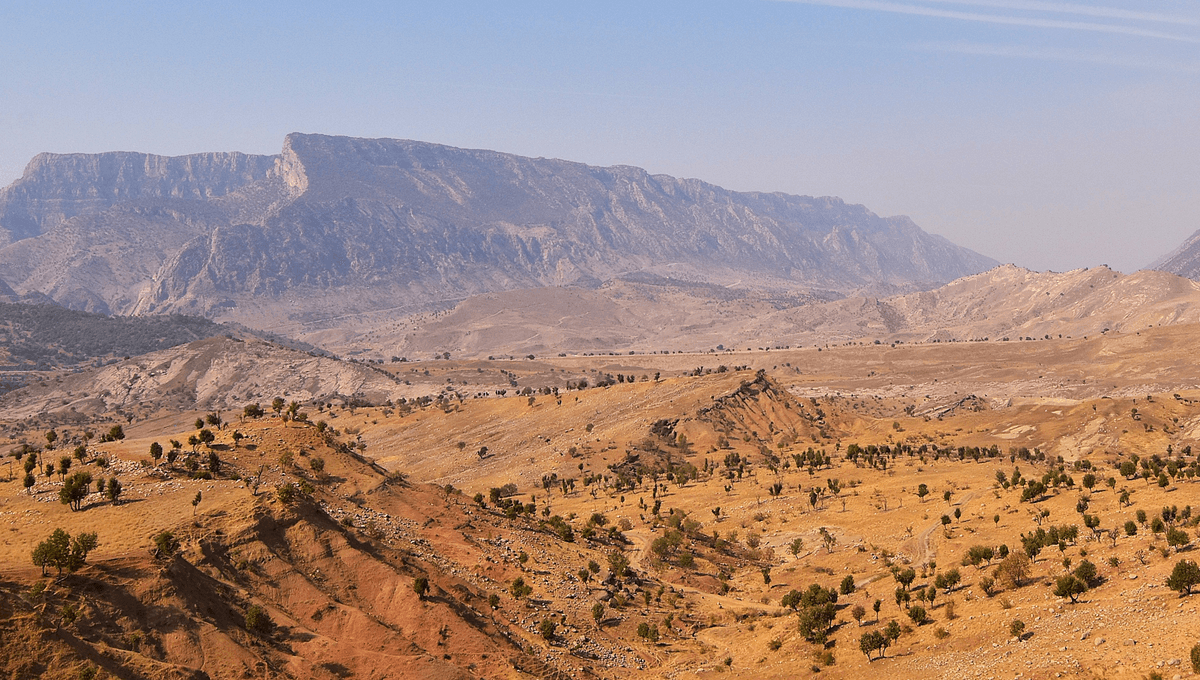

The rest of this article is behind a paywall. Please sign in or subscribe to access the full content. The question of why agriculture started when and where it did is one of the big mysteries of how we came to be. The fact that the first evidence for agriculture appeared in many unconnected places relatively soon after the end of the last ice age suggests climate played a big part, but in most of those locations, we lack good records of the local conditions at the time. Although claiming to be the first centers of civilization is a matter of national pride, the Fertile Crescent is generally considered the favorite, making limestone caves in the Zagros Mountains (where Homo sapiens and Neanderthals got it on long before) a prime place to look. Stalagmites and stalactites, collectively known as speleothems, can record climatic conditions over the period of their formation through changes to their isotopes. In the case of a stalagmite from Kurdish Iraq, that period overlaps with one of the most important developments in human history: the birth of agriculture and the development of villages and cities. The stalagmite reveals that around 14,560 years ago, rainfall increased in the area, leading to faster deposition of limestone. Around 12,700 years ago, precipitation reduced, and conditions became dustier, indicated by increased concentrations of trace elements like barium, strontium, zinc, and sodium in the limestone layers. Hsārok Cave sits well inside the Fertile Crescent. Rainfall there is currently sufficient for agriculture, and tributaries of the Tigris River, along whose banks some of the earliest civilizations flourished, flow nearby. A sample of stalagmite KR19-3 from Hsārok Cave. Image Credit: Eleonora Regattieri Archaeological evidence suggests Palegawra Cave, 140 kilometers (87 miles) from Hsārok Cave, was frequently occupied in summer during the initial warmth as the glaciers retreated, but largely abandoned around the time the stalagmite indicates the region dried out. Occupation became common again just as Hsārok Cave was recording evidence of renewed warmth. The authors propose that until the Holocene era began, the foothills of the Zagros Mountains “created a mosaic of spatially restricted, yet resource rich, environments. While these were not suited to supporting large, year-round settlements, they encouraged mobility, allowing people to exploit seasonally available resources across different elevations and ecotones, such as open-woodland, grassland, and riparian habitats.” The authors argue that the flexibility of living under such conditions promoted the building of a culture that, when the climate became warmer and more stable, was well-suited to taking advantage of new opportunities, including agriculture. Speleothems can be read in multiple ways, and sometimes this produces a conflicting and confusing picture. However, the Hsārok Cave stalagmite tells a consistent tale. The ratios of carbon-13 to carbon-12 reveal faster local plant growth during times that oxygen-16 and -18 ratios suggest were warmer and wetter, as we would expect. Just as importantly, the picture fits well with evidence from multiple Greenland Ice cores. The local wet period that the stalagmite records coincides with the Bølling–Allerød interstadial, when Greenland first warmed significantly from the depths of the last glacial maximum. The subsequent drying matches the Younger Dryas Period, when the Earth, and particularly the North Atlantic Basin, experienced a still unexplained cooling. The study is published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.